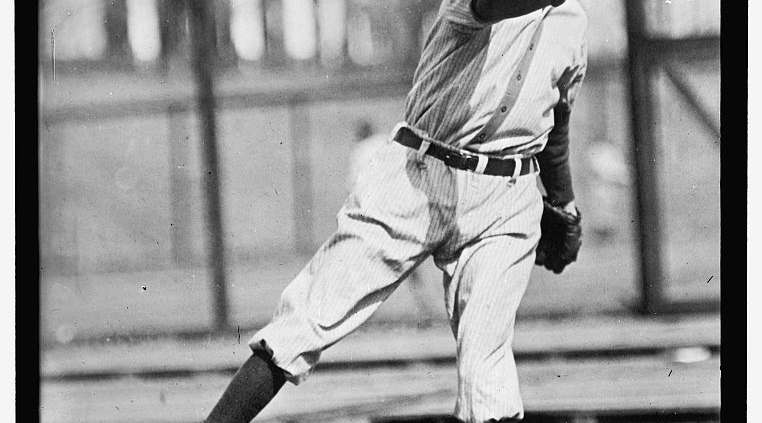

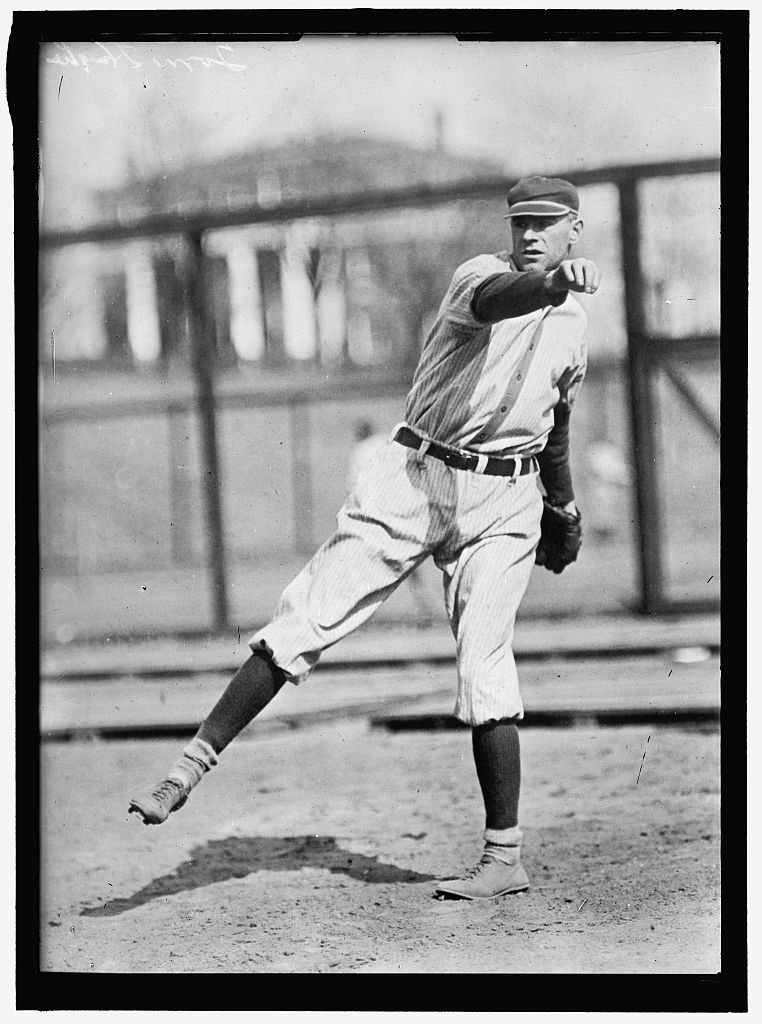

Long Tom Hughes

Long Tom Hughes mixed a happy-go-lucky lifestyle with a Chicago-tough pitching moxie. Tall for his time at 6-foot-1, he stayed at about 175 pounds throughout his career. A heavy smoker and drinker, he took no particular care of his body, yet managed to stay in the major leagues until nearly age 35, and in the semi-pro ranks past age 40. Hughes loved being on the mound, at the center of the game. He had an outstanding drop curveball, a good change of pace that helped his fastball, and a rubber arm. After throwing 200 or more innings every year from 1903 to 1908, Hughes’s arm finally gave out, and he spent the 1910 season in the minors. Yet, in this age before reconstructive surgery, Hughes then succeeded in doing what few pitchers of his era could: he came back from a lame arm, and pitched three more seasons in the major leagues, winning 28 games for the Senators from 1911 to 1913. “Prize fighters might not be able to come back,” Alfred Spink observed prophetically in 1910, “but good, old, sturdy, big-hearted athletes like the grand old man, Hughes, can.”

Long Tom Hughes mixed a happy-go-lucky lifestyle with a Chicago-tough pitching moxie. Tall for his time at 6-foot-1, he stayed at about 175 pounds throughout his career. A heavy smoker and drinker, he took no particular care of his body, yet managed to stay in the major leagues until nearly age 35, and in the semi-pro ranks past age 40. Hughes loved being on the mound, at the center of the game. He had an outstanding drop curveball, a good change of pace that helped his fastball, and a rubber arm. After throwing 200 or more innings every year from 1903 to 1908, Hughes’s arm finally gave out, and he spent the 1910 season in the minors. Yet, in this age before reconstructive surgery, Hughes then succeeded in doing what few pitchers of his era could: he came back from a lame arm, and pitched three more seasons in the major leagues, winning 28 games for the Senators from 1911 to 1913. “Prize fighters might not be able to come back,” Alfred Spink observed prophetically in 1910, “but good, old, sturdy, big-hearted athletes like the grand old man, Hughes, can.”

Thomas James Hughes was born in Chicago on November 29, 1878, the fifth surviving child of Patrick and Bridget McNally Hughes, Irish immigrants who had arrived in the United States as children prior to the end of the Civil War. The son of a common laborer, Tom escaped the same fate by honing his skills as a pitcher on the city’s sandlots around Ashland and Wabansia avenues. A younger brother, Ed, also became a pitcher, eventually spending parts of two years with the Boston Americans.

Purchased by the Chicago Orphans (later Cubs) from Omaha of the Western League in September 1900, Tom pitched a major league career-high 308⅓ innings for the Orphans the following year. Despite a lackluster 10-23 record, Hughes’s occasional brilliance on the mound (including a 1-0, 17-inning victory over Bill Dinneen), aroused the interest of two American League managers, Connie Mack of the Philadelphia Athletics and John McGraw of the Baltimore Orioles. McGraw outbid Mack for Hughes’s services, and Tom reported to Baltimore for the 1902 season.

Long Tom’s stay in Baltimore was brief. In July, 1902, McGraw returned to the National League, and the syndicate of NL managers that controlled the Baltimore franchise set about selling off much of the Orioles roster. Hughes, nursing a sore arm, was released to the Boston Americans. For the final two and a half months of the season, Hughes started eight games for the Americans, going 3-3 with a 3.28 ERA. When Boston charged to the pennant in 1903, Hughes became, along with Cy Young and Bill Dinneen, the third axis in Boston’s trio of standout starting pitchers. For the year, Hughes posted a 2.57 ERA and finished with a career-high 20 wins against only 7 losses. Picked to start the third game of that year’s World Series, Hughes fared poorly, lasting only two innings in a 4-2 defeat to the Pirates.

That offseason manager Jimmy Collins traded his young 20-game winner to the New York Highlanders for Jesse Tannehill. According to one writer, Collins made the deal because he “had some trouble in holding Tom in the straight path.” Hughes started just 18 games for New York before being traded once again. On July 20, 1904, the Highlanders shipped Hughes and fellow pitcher Barney Wolfe to the Washington Senators for Al Orth. In going to Washington, Hughes joined one of the worst teams in baseball history. On their way to a 38-113 record in 1904, the Senators would finish no higher than seventh place for the rest of the decade. From 1904 to 1909, Hughes pitched in 184 games for this feeble outfit; he lost 85 of them.

Though a subpar defense and lack of run support consistently hampered his efforts, Hughes was much admired in Washington, where his intimidating mound presence and electric assortment of pitches set him apart from his teammates. Armed with an above-average fastball and a willingness to throw it near a batter’s head to make a point, Hughes kept opposing hitters off-balance, sprinkling in the occasional insult for good measure. Hughes “is one of the most original ‘goat getters’ in the business,” one writer observed. “When pitching he keeps up a verbal broadside against every batter he faces.”

In 1905, Hughes enjoyed one of his best seasons in Washington, finishing the year with a 2.35 ERA in 291⅓ innings, though his 17 wins were offset by 20 losses. He pitched six shutouts, five over the same team, the Cleveland Naps. “His one ambition this season has been to be the master of that team of heavy-hitters at Cleveland,” the Washington Post reported. “And now that he has succeeded…the baseball world is talking about his achievement. Hughes is regarded by ball players as one of the most skilled pitchers in either big league. They claim he has no superior when he wants to exercise all his pitching talents. But Tom doesn’t always feel that way.” At season’s end, one Washington paper collected money for a fan testimonial for ‘Long Tom.’ In appreciation for his efforts, the fans presented Hughes with a diamond scarf pin in the shape of a fleur-de-lis.

But the love affair was not mutual. Frustrated by pitching for the league’s doormats, Hughes slumped in 1906, as he posted a 7-17 record with an awful 3.62 ERA. Late in the season, Hughes quit the team, declaring, “The American League is a joke. I am tired of being the scapegoat of the Washington club for the last two years….Rather than come back to Washington, I will join an amateur club or play with the outlaws. This proposition of being the fall guy for the bunch is not what it is cracked up to be. No more of it in mine. I am through with Washington for good.” The Washington Post reported that manager Jake Stahl had already suspended Hughes, for “being too friendly with the cup that cheers.”

In the offseason, Stahl was replaced as manager by Joe Cantillon, and Hughes returned to the Senators for spring training. It turned out to be another rough year for Hughes and the Senators, as Long Tom posted a 7-14 record and articles about the club featured headlines such as “TEAM DOES BEST IT CAN” and “SHOULD PRACTICE BUNTING.” Washington finished the year with a 49-102 record, 43½ games out of first place.

With the emergence of Walter Johnson, the Senators improved to 67 wins in 1908, and Hughes enjoyed his first winning season in a Washington uniform: 18-15 with a 2.21 ERA. Tom re-signed for the 1909 season, and felt sufficiently hopeful about Washington’s prospects that he specifically asked not to be traded. “I want it understood…that I don’t want to figure in any deals,” he told the Post. “I want to stay right here in Washington as long as I can pitch ball. No trades for mine. I like this old town, and now that the team has some prospects of being in a race, I am more anxious than ever to stay here.”

Unfortunately for Hughes and the Senators, things did not work out as planned. The Senators won only 42 games, and chronic soreness in his pitching arm limited Tom to just 13 starts and four victories before he was sold on waivers to the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association. For the Deadball Era, it was a familiar story: the sore-armed pitcher who quietly disappears from the league, never to be heard from again. But Hughes would be different. By July 1910, the Post was reporting that Hughes was “mowing down” batters for Minneapolis, striking out as many as ten in one outing and winning two-thirds of his games. Hughes finished the season as the league-leader in wins (31), strikeouts (222), and winning percentage (.721), and the Millers won the pennant going away with a 107-61 record. That September, the Senators repurchased Hughes, and the following spring he was back with Washington.

Arm trouble continued to plague Hughes during his comeback, however. In 1911, he gutted his way through 223 innings for the Senators, finishing with a respectable 3.47 ERA. The following year he was better, lowering his ERA to 2.94 and posting a 13-10 record. Though advancing in years, Hughes never lost his combative spirit. When a crank challenged his pitching effectiveness in a Chicago saloon, Hughes invited him to settle their differences outside. It took five police detectives to separate the two men, who bloodied each other so badly that one passer-by incorrectly assumed they were slashing each other with knives. Both Hughes and his fellow pugilist spent the night in jail, where they shook hands and declared the matter settled.

Tom’s arm gave out again in 1913. After finishing the year with a 4-12 record and 4.30 ERA, Washington released Hughes to the Los Angeles Angels of the Double-A Pacific Coast League. Although he subsequently pitched 10 seasons in the minor leagues, he never pitched in the majors again. Upon examining their new pitcher, the Angels were delighted to find that in addition to now being a crafty veteran, Hughes still had plenty of movement and zip on his pitches. In 1914 he was 24-16 with an ERA of 1.91 in a career-high 348 innings. With the Angels again in 1915, Tom pitched well in the early part of the season, posting a record of 19-16, as his team competed for first place. The Angels, however, faded badly and management decided to release Hughes. In both 1916 and 1917 Tom pitched for Salt Lake in the same league. In 1920, Tom split the season between Sacramento and Los Angeles. Starting in 1921, Tom pitched four consecutive seasons with the Angels and logged over 200 innings each year. He faltered in 1926 and the Angels released him. In 1926, Tom ended his professional pitching career at age 47 as he pitched for both Little Rock and Beaumont at the Single-A level.

Following his retirement, Tom returned to his native Chicago. Married to Ida Elletsen in 1904, the couple had seven children, six sons and one daughter. After pitching in the semipro circuit for several years, Hughes worked in a tavern, and later as a groundskeeper for the Chicago park system. He spent the rest of his life in his beloved hometown, dying there at age 77 on February 8, 1956, of pneumonia. He was buried in St. Joseph Cemetery, in nearby River Grove, Illinois.

Note

This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

John Thorn and Pete Palmer. Total Baseball. Total Sports, 2001.

Thomas James Hughes’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Dennis Snelling. The Pacific Coast League: A Statistical History.

Washington Star

Los Angeles Times

Chicago Tribune

4

Full Name

Thomas James Hughes

Born

November 29, 1878 at Chicago, IL (USA)

Died

February 8, 1956 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.