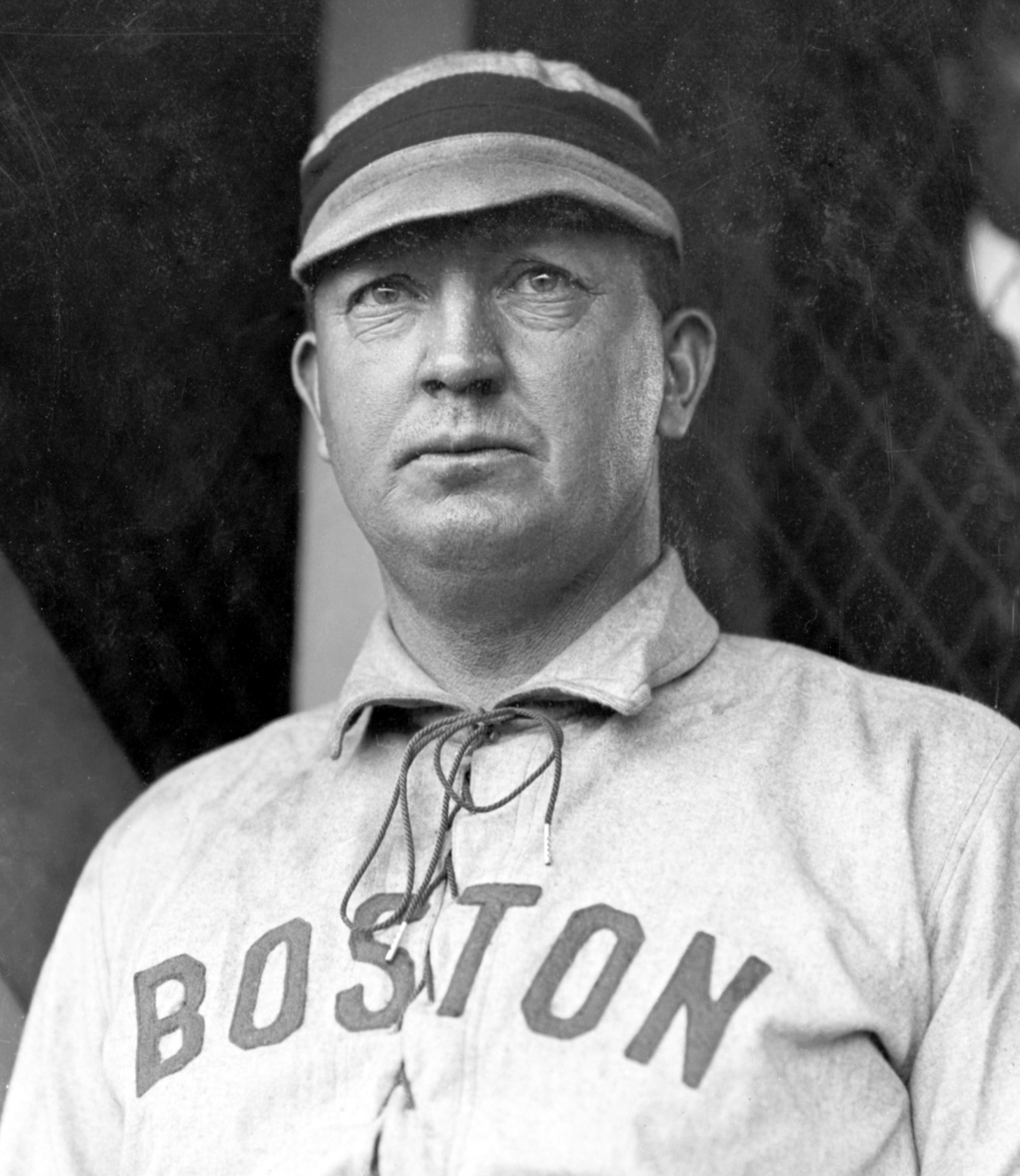

Cy Young

Cy Young is a name familiar to all but the most casual of baseball fans, well over 100 years after his pitching career ended. After all, he is the one the Cy Young Award is named after, the award given every year to the best pitcher in each league. Young also holds numerous baseball records, including some that are unlikely to be broken, including both the most wins by any pitcher (511) and the most complete games (749).1

The years in which Young pitched in the major leagues (1890-1911) saw a number of significant changes in baseball, which included an increase in the distance from the pitcher’s mound to home plate, and the introduction of the foul strike rule.2 Sixteen times Young was a 20-game winner, and in five of those seasons he was actually a 30-game winner. There were even three seasons when he lost more than 20 games, but each time he came back and won as many as or more the following year.

He was present at the birth of the American League and threw the first pitch ever thrown in a World Series game. Winning two games in the 1903 World Series, Young also stands as the only pitcher to win a game in both the Temple Cup, the postseason championship series that had obtained in the National League in the years 1894-1897, and in the World Series, which began in the twentieth century.

Denton True Young was born on March 29, 1867, in Gilmore, Ohio, the oldest of five children of McKinzie Young Jr. and Nancy (Miller) Young. Gilmore was a small farming community about 100 miles south of Cleveland, and the Young family was raised on a farm owned by McKinzie’s father, McKinzie Sr. “Dent’s” education stopped after the sixth grade at the town’s two-room school so he could help his parents with farming chores, but it was also at this time that he discovered the game of baseball. Encouraged by their father, who had been a private in the Union Army during the Civil War, the Young boys played baseball every chance they got. Developing into a better pitcher than hitter, Denton practiced throwing during lunch breaks from farm work (“I usta kill squirrels with a stone when I was a kid.”)3 Besides practicing and playing in recreational games, he organized his own team in Gilmore, then in the summer of 1884 he played on semipro teams in Newcomerstown, Cadiz, and Uhrichsville, Ohio.

Young did not enter professional baseball at a young age. As of 1888, he was still playing semipro ball in Carrollton, Ohio, earning $1 a game.4 In 1889 he played for Leesburg and New Athens, Ohio. Professional teams began to bid for his services.

Young hoped to one day marry the girl from the adjacent farm, Robba Miller, and he saw an opportunity to make money playing baseball. For $60 per month, he signed for the 1890 season with Canton, Ohio, of the Tri-States League. He was 23 years old.

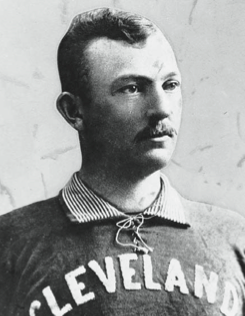

It was in Canton during the preseason that Young picked up the moniker “Cyclone.”5 During the 14 weeks he played for Canton, he started 29 games and relieved in two. He was 15-15 for a team that finished last, but struck out 201 batters while walking only 33.6 His final game for Canton was on June 25 at Pastime Park. He threw a no-hitter, and struck out 18 batters without walking a man.7 A few days later, Young’s contract was purchased by the National League’s Cleveland Spiders for $300, and a few days after that, the Canton ballclub’s season ended.8

Young’s quick ascendancy to the majors was the result of the emergence of the ill-fated Players League, which forced National League teams to dig deep into the minor leagues for any available talent. Young’s weight is listed as ranging from 170 pounds in his younger years to 210 pounds. He pitched his first major-league game on August 6, 1890, against Cap Anson’s Chicago Colts. Before the game, Anson reportedly called Young “just another big farmer.”9 Young threw a three-hitter, beating the Colts 8-1. His opponent was 41-game winner Bill Hutchison. Young had his first big-league win. He won his next two starts as well. But the Spiders were a seventh-place team that year and finished 44-88, Young ended the season with a record of 9-7, by virtue of pitching and winning both games of a doubleheader on the final day of the season. He recorded a 3.46 earned-run average in that first partial season, striking out 39 and walking 30. He was the only Spider with a winning record.

Young’s quick ascendancy to the majors was the result of the emergence of the ill-fated Players League, which forced National League teams to dig deep into the minor leagues for any available talent. Young’s weight is listed as ranging from 170 pounds in his younger years to 210 pounds. He pitched his first major-league game on August 6, 1890, against Cap Anson’s Chicago Colts. Before the game, Anson reportedly called Young “just another big farmer.”9 Young threw a three-hitter, beating the Colts 8-1. His opponent was 41-game winner Bill Hutchison. Young had his first big-league win. He won his next two starts as well. But the Spiders were a seventh-place team that year and finished 44-88, Young ended the season with a record of 9-7, by virtue of pitching and winning both games of a doubleheader on the final day of the season. He recorded a 3.46 earned-run average in that first partial season, striking out 39 and walking 30. He was the only Spider with a winning record.

In 1891 Young was the ace of the Spiders staff. The team finished fifth, but still with a losing record, 65-74. Young was a 20-game winner, however — in fact, a 27-game winner. He was 27-22 (2.85) in 55 games, 46 of them as the starter (he worked 43 complete games, throwing 423⅔ innings.) He was still doling out too many bases on balls, walking 140 opponents while striking out 147.

Though he had pitched a number of very good games, Young’s first shutout came on April 15, 1892, when he beat Cincinnati 2-0. Fellow pitcher Nig Cuppy had an excellent 28-13 season, but Cy Young led the league in both wins and winning percentage (36-12), with a league-leading 1.93 ERA. His nine shutouts also led the league. The team finished in second place, but with two 35-game winners (Kid Nichols and Jack Stivetts, with identical 35-16 records, and a 22-game winner in Harry Staley to boot), the Boston Beaneaters were hard to beat. Boston finished 8½ games ahead of Cleveland. The two teams played a postseason “World Series” and the first game pitted Young against Stivetts. Neither pitcher gave up a run; the game ended 0-0 after 11 innings due to darkness. Boston won the series. Young’s first year of postseason play, however, ended with him 0-2, having lost the third game, 3-2, and the sixth and final game, 8-3.

After the 1892 season, Young married Robba Miller on November 8.

Between the 1892 and 1893 seasons, a significant change was implemented: the distance between the pitcher and batter was increased from 55 feet 6 inches to 60 feet 6 inches. Unsurprisingly, this helped the offense and thus did something of a number on Cy Young’s ERA, which climbed to 3.36. Despite struggling to make the adjustment, pitchers still won games and lost them and Young was 34-16. He had finished strong, winning 16 of his last 20 decisions. He walked one more batter than he struck out (103-102), but averaged only 2.2 walks per nine innings, best in the league. It was a statistic in which Young led the league 14 times. From 1893 through 1901, he led the league nine years in a row in a stat that one could argue best represented control. (In fact, his strikeouts-to-walks ratio of 0.99 was best in the league, too, among qualifying pitchers.)

In 1893 Young’s ERA increased by 1.43 runs per game, and the league as a whole similarly saw an increase from 3.28 runs to 4.66 (1.38). And the next year (1894) the league ERA increased to 5.33. Young’s went up, too, to 3.94, which we now see as the worst of his career. At one point, he lost seven decisions in a row. The 1894 Spiders dropped to sixth place; Young was 26-21.

In 1895 Young won 35 games and lost only 10. He struck out 121 and only walked 75. He brought his ERA down to 3.26, and the Spiders finished in second place, three games behind the Baltimore Orioles. The top two teams in the National League faced off in the best-of-seven postseason Temple Cup series. Young won Games One, Three, and the clinching Game Five.

He started slow in 1896, but then went on a 14-4 tear and on July 23 pitched a masterpiece, a no-hitter through 8⅔ innings, giving up a hit (to future Hall of Famer Ed Delahanty, who was on his way to a season in which he hit for a .397 batting average), then retiring the next batter to win the game. He was 28-15, with an ERA that was basically stable (3.24). His 140 strikeouts led the league. At some point during the season, Young started doing something he hadn’t done before in his career — he started wearing a glove. Heretofore he had pitched without a glove on.

Young also did something else in 1896 — he umpired in a game. In fact, he umpired in two games. If the umpire failed to turn up, teams typically agreed upon someone to perform the role. On June 19, something else happened. In the seventh inning, umpire Tom Lynch not only ejected Cleveland manager Patsy Tebeau but had to be physically restrained from assaulting him, held back by Chicago players. Lynch refused to umpire the rest of the game, so the teams decided to ask Young to umpire, along with the Chicago Colts’ Con Daily.10

On July 29 in Cincinnati, Young umpired a second game when the scheduled arbiter didn’t show up. The Cincinnati Reds provided Frank Foreman and the Spiders provided Young. In July 1903, Young umpired two games in the American League. Young played baseball at a fractious time, but was widely respected for his probity. Never once was he ejected from a ballgame.

Young’s 1897 season saw him a 20-game winner for the seventh season in succession (21-19), but his ERA rose half a run to 3.78. One of his wins was his first no-hitter, on September 19, a 6-0 win over Cincinnati. The Reds batters, wrote the Cleveland Plain Dealer, “walked up to be slaughtered only because the rules required and not for the good it did them.”11 Cleveland finished in fifth place again. By the time the season was over, Young had 216 wins to his credit.

Young’s ERA improved dramatically in 1898, more than a full run, from 3.78 to 2.53. He was 25-13 for another fifth-place club. In 46 games, including 40 complete games in 41 starts, he walked only 41 batters. It was his last year pitching for Cleveland.

This isn’t the place to go into the story of how brothers Frank and Stanley Robison came to own not just the Cleveland club but also the St. Louis team, too — the Perfectos. With no prohibition against it, they concentrated their best players in St. Louis. On paper, it was simply a matter of assigning the player’s contract from one team to the other. Young had another excellent year, for St. Louis: 26-16 (2.58), another 40 complete games, and only 44 walks in 44 games.

In 1900 St. Louis changed its name to the Cardinals. The National League contracted from 12 teams to eight, so any pitcher was inevitably facing a better array of hitters. After nine consecutive seasons of 20 or more wins — every season since his first, which was only a partial season — Young finished one win shy: 19-19. He actually thought he had won 20 games, and it was reported as such at the time in both The Sporting News and the Spalding Guide but, according to Reed Browning, later reconstruction of the historical record (including regularizing scoring rules) deprived him of one victory. The count at the time showed Young with 20 wins, and had everyone believed he was one win short of the number, there were two opportunities that might have been handled otherwise and given him a shot to reach 20.12

When the syndicate of owners that controlled both the Cleveland and St. Louis franchises shifted Young to St. Louis in 1899, the pitcher’s overpowering fastball began to lose some of its steam. His failure to win 20 games in 1900 resulted because a bruised rib suffered in a collision with the New York Giants’ Ed Doheny caused him to miss significant playing time for the first time in his career. Additionally, as the summer progressed and Young suffered his share of tough losses, the normally quiet and reserved star uncharacteristically vented his frustration, charging into the stands on August 20 to confront a heckler who had accused him of quitting on the team. The Perfectos slumped into fifth place, 10 games below .500.

After the 1900 season, Young jumped to the nascent American League and won well over 20 games for each of the next four seasons, averaging more than 27 wins per year and twice topping 30 victories. Honus Wagner, who regularly faced Young in the National League toward the end of the decade, thought Young had the greatest fastball he had ever seen. “Walter Johnson was fast, but no faster than Rusie,” Wagner observed. “And Rusie was no faster than Johnson. But Young was faster than both of ’em!”13 Another contemporary, Cap Anson, observed that when the 6-foot-2, 210-pound Young unleashed his speed, it seemed as if “the ball was shooting down from the hands of a giant.”14

After the 1900 season ended, several St. Louis players defected to the American League, including catcher Lou Criger, Young’s batterymate, who signed with Boston. Though he was hounded by Boston’s owner, Charles Somers, for several weeks, the cautious Young did not sign with the Americans until March 19, 1901. St. Louis owner Frank Robison had declined to match Boston’s salary offer of $3,500, insisting that Young, about to turn 34, was just about all washed up.15

Along with that of Napoleon Lajoie, Young’s defection to the American League in 1901 generated instant credibility for the upstart circuit. The winner of 286 games in his first 11 seasons, Young had established himself as a model of consistency and excellence, pitching more than 300 innings every year from 1891 to 1900 and ranking among the National League’s top five in earned-run average six times during that span. Still, cracks were starting to show in the great pitcher’s façade. At 34, Young had already entered the phase of his career when most pitchers start to break down. Indeed, in 1900, some opposing batters attested that Young was more hittable than ever, and newspaper reporters began routinely affixing the adjective Old in front of his name. By all appearances, then, when the Boston Americans signed Young, his agreement secured by a three-year contract, the acquisition might have been thought to represent more a public-relations coup than a legitimate pitching upgrade.

As it turned out, Boston, not to mention the rest of the American League, got much more than it could have expected. He demonstrated that he was far from washed up.

During his eight years with the Americans (later called the Red Sox), Young won 192 games, becoming the first major-league hurler to pitch effectively into his 40s.16 In 1901, his first season with the Americans, one can argue that he had the advantage of facing competition watered down by the sudden addition of eight new major-league teams. Nonetheless, Young enjoyed one of the greatest pitching seasons in baseball history. Though he lost his first start, on April 30 he won the first game in Red Sox history, thanks to Buck Freeman’s game-tying two-run homer in the ninth inning and two more Boston runs in the 10th. The 8-6 win was also the first extra-inning game in American League history.

On May 8, 1901, Young won the Americans’ first home game, beating the Philadelphia Athletics, 12-4. He led the league in victories (33), strikeouts (158), and earned-run average (1.62), a feat now called pitching’s Triple Crown. He also led the league in shutouts (5). In 371⅓ innings, he walked just 37 batters. Asked to explain his success, Young said, “I have almost perfect control of the ball this year, and I try to keep it bumping over the plate. If two or three men get on bases, I put on a little more steam and shoot ’em over as fast as I can — but I try all the time to keep ’em over.”17 Sporting Life suggested that Young was “like wine … better with age.”18 And, counting 1902, he still had five more 20-win seasons in him.

The many photos of Young that survive from this period portray a man advancing in years and gaining in weight. But as his girth expanded, his control sharpened; five times after 1900 he led the league in fewest walks per nine innings. And though his fastball lost some of its zip, the wily Young more than made up for it with a pair of curveballs, one thrown overhand with a sharp break, the other thrown side-arm with a sweeping arc. Both pitches were delivered from a variety of arm angles; occasionally Young even threw submarine-style to upset the batter’s timing. In his continued mastery of opposing batters in the face of declining strength and advancing age, Young raised pitching to an art form, and earned his place in baseball’s pantheon of all-time greats. “If I were asked who was the greatest pitcher the game ever knew, I would say Cy Young,” sportswriter Francis Richter wrote in 1910, when Young was 43 years old. “Cy is now pitching as good ball today as he did twenty years ago.”19

From late February into early April of 1902, Young even took a position as pitching coach of the Harvard baseball team.20

Over the next three seasons (1902-04), the American League’s talent pool expanded vastly as more players made the jump to the junior circuit, but Young remained unfazed by the new arrivals. He led the league in victories in 1902 and 1903, and finished second in 1904. His 32-11 mark in 1902 was the fifth time he’d won more than 30 games (1892, 1893, 1895, and 1901 were the other seasons.)

In 1903, the American League adopted the “foul strike rule” that the National League had adopted in 1901. It’s the same rule fans are familiar with ever since: The first two foul balls struck by a batter counted as strikes. Before that, fouls simply did not count. Needless to say, the rule was of benefit to pitchers. But pitchers still won and lost games, and Young won more than any of his counterparts.

Though he began to rely more exclusively on his assortment of breaking pitches, Young’s control remained as sharp as ever: In 1904 he walked just 29 in 380 innings while striking out an even 200.

There was a remarkable road-trip stretch in 1903, when Young beat Detroit 1-0 on June 23, then beat St. Louis 1-0 on June 28, and beat Chicago 1-0 on July 1, in 10 innings. Throwing back-to-back-to-back 1-0 games had never been done before, and has never been done since.

In 1903, Young had his best season at the plate, batting .321 in 137 at-bats. Only outfielder Patsy Dougherty (.331) hit for a higher average on the Red Sox; the team average was .272 that year. Young’s lifetime mark was .210, however, and he didn’t get on base much more often than that. (He had a .234 career on-base percentage.) He drove in 290 runs, and scored 325. He homered 18 times. As a fielder, working on rougher fields, Young had a major-league .939 fielding percentage.

Young’s prowess on the mound helped the Americans win back-to-back pennants in 1903 and 1904, and though teammate Bill Dinneen stole the spotlight in Boston’s best-of-nine victory over Pittsburgh in the first modern World Series (1903), Young aided the cause with a 2-1 record and a 1.85 ERA. He threw the first pitch in a modern World Series and, after giving up four runs in the first inning, suffered the first loss, 7-3.

In the best-of-nine Series, Young won Game Five in Pittsburgh, 11-2, preventing the Pirates from taking a four-games-to-one lead, and won Game Seven, 7-3, giving Boston a four-games-to-three edge and setting the stage for the triumphant clinching game back in Boston three days later, a 3-0 shutout for Dinneen.

Young’s greatest achievement may have come on May 5, 1904, when at the age of 37 he pitched the first perfect game in American League history — just the third in the major leagues and the first from the 60-foot-6-inch pitching distance. Losing pitcher Rube Waddell of the Philadelphia Athletics, who had defeated Young in their previous encounter a week earlier, taunted the old pitcher, promising to beat him again. After Young pitched his masterpiece and Boston won, 3-0, Cy uncharacteristically returned fire, shouting to Waddell, “How did you like that one, you hayseed?”21 It was Young’s second career no-hitter (his first came in 1897); he would pitch a third in 1908, against the New York Highlanders.

Young’s perfection against the Athletics came in the midst of a major-league record 24 consecutive innings in which the pitcher did not allow a single hit, as well as a scoreless innings streak that stretched to a then-record 45 innings.22 “And they said Uncle Cy was all in, did they?” observed Boston catcher Duke Farrell of his 37-year-old teammate. “He fooled them, didn’t he?”23 Down the stretch, Young continued to impress, pitching shutouts in each of his last three starts to help the Americans to their narrow pennant victory over the Highlanders. In 1938, Johnny Vander Meer threw no-hitters in consecutive starts but even so, his streak of hitless innings topped out at 22.

Boston won the 1904 pennant, helped in good measure by Young throwing three consecutive shutouts (increasing his season total to 10) in his final three starts — October 2 (2-0), October 5 (3-0), and beating New York in Boston in the second game of an October 8 doubleheader, 1-0. After that win the two teams traveled to New York, and Boston won the pennant by winning the first game of two scheduled for October 10. The Americans would have gone on to play the New York Giants in the World Series, but the Giants refused to play them. Even the New York press fiercely mocked Giants owner John T. Brush for denying baseball fans the opportunity to see the top team in each league play a head-to-head postseason series.

Boston plunged in the standings in 1905, to fourth place, 16 games behind the Athletics, and then all the way to the cellar in 1906, an incredible 45½ games out of first. Their record was 49-105 (.318).24 Only in 1932 (43-111, .279) did the team have a worse season.

Proving the point that it takes a team to win, Young lost one more game than he won in 1905 (18-19), despite a 1.82 ERA that was third in the league. In 1906 he was 13-21 with a 3.19 ERA, but his .382 winning percentage was still 64 points better than the team’s. Remarkably, in both years, Young’s FIP led the majors. Fielding Independent Pitching is a statistic designed to measure a pitcher’s effectiveness at preventing home runs, walks, and hit batsmen, and in striking out opponents — four things that are within the control of the pitcher and not dependent on his fielders.

But 1906 was a year in which Young started the season 1-8 and failed to shut out the opposition even once.

Almost three-quarters of the way through the 1906 campaign, Chick Stahl had succeeded Jimmy Collins as manager of the 1906 Bostons. Near the end of 1907 spring training, however, he unexpectedly committed suicide. Young stepped in and managed the team for the few spring-training games that remained as well as the first six games of the regular season. The team was 3-3 when he handed the reins over to George Huff, the first of four managers for the 1907 team. Young returned to good form in 1907, with another 20-win season. He threw six shutouts and recorded a 1.99 earned-run average; he was 21-15 for the seventh-place team. In early September, he and his wife became parents for the first time, only to lose their daughter a few hours after she was born. On September 9, he pitched a 13-inning scoreless tie game against Rube Waddell, but he lost all four games he started after that.

The Boston Americans became the Boston Red Sox in 1908 and Cy Young had another superb season. He won his first four games by scores of 3-1, 8-1, 7-0, and 5-1. And on May 30, he threw a one-hitter, beating Washington 6-0 in the first game of a morning-afternoon doubleheader. On June 30 he topped that, throwing a no-hitter and a near-perfect game against the Highlanders. He walked the leadoff man, Harry Niles, but Niles was thrown out trying to steal second and Young disposed of the next 26 batters without a man reaching base. It was the third no-hitter of his career. The Boston Journal suggested that the walk had been a “gift of the umpire.”25 Young even drove in four of Boston’s eight runs.

Young was 41 years old. At season’s end, he had an ERA of 1.26 (second only to Addie Joss’s 1.16) and a record of 21-11. The team finished fifth, at 75-79.

In the wake of Young’s historic accomplishments, much of the baseball world began to acknowledge his unparalleled place in the pantheon of great pitchers. “Rusies have come and gone, in their turn, by Cy Young still pitches on,” observed the Detroit Tribune. “Perhaps no ballplayer ever lived who paid stricter attention to business and who came out of a long series of honors showered on him with lesser opinion of himself and with such strict attention to temperate habits.”26 For his part, Young placed no special emphasis on his remarkable durability and longevity. He downplayed the significance of his offseason conditioning program, which consisted mostly of splitting wood at his Peoli, Ohio, farmhouse. “It isn’t any secret,” Young said, “just outdoor life, moderation, and a naturally good arm. I don’t know that I take any better care of myself than any other pitcher does, it just happens, this thing of my lasting. It isn’t the result of any system.”27 The farm featured corn, chickens, and sheep. Young apparently also raised hunting dogs and “constructed and sold large trunks, fashioned to meet the needs of traveling ballplayers and widely used in the major leagues.”28

In an era when ballplayers were often regarded as dissolute, inveterate slackers, Young won praise for his clean living and moderate temperament. He prided himself on his work ethic, and reacted with indignation when accused of easing up with a big lead. “When you see me let any club make runs off my pitching on purpose,” he snarled, “come around and I’ll give you a brand new hundred dollar bill.”29 Easing up, he declared, placed the game “on the level with lawn tennis, tiddle-de-winks, or some other schoolgirl frivolity.”30 Later in life Young articulated a personal philosophy for playing the game the right way by enumerating five rules of conduct: 1) Be moderate in all things; 2) don’t abuse yourself; 3) don’t bait umpires; 4) play hard; and 5) render faithful service to your employer. Adhering to this creed, Young continued to enjoy success long after other pitchers had left the game. Thus, his unbreakable career records (511 victories, 7,354⅔ innings, 749 complete games) were the product not just of exceptional talent and good fortune, they were also the result of his own exacting standards.

Young won 477 complete games, fully 60 more than Walter Johnson. Only five times did he win a game that he had started but not completed.31

As Young approached and then passed his 40th birthday, he continued to rank among the game’s best pitchers, thanks in large part to the wide assortment of breaking pitches and arm deliveries he employed to fool opposing batters. “If a right-hander crowded my plate,” Young said after retiring as a player, “I sidearmed him with a curve, and then, when he stepped back, I’d throw an overhand fastball low and outside. I was fortunate in having good speed from overhand, three-quarter, or sidearm. I had a variety of curves — threw a so-called screwball or indrop, too — and I used whatever delivery seemed best. And I never had but one sore arm.”32 After enduring the worst season of his career in 1906, when he finished the year 13-21 for the woeful (49-105) Americans with a terrible 3.19 ERA, Young came back strong in 1907 and 1908, winning 21 games in each season and posting ERAs of 1.99 and 1.26, respectively. The 1906 season was the third year in which he’d lost 20 or more games; in 1891 he had been 27-22 and in 1894 he had been 26-21.

Lest we forget, pitchers and batters both lacked the analytic tools offered today by video and computers. They also typically worked without the kind of professional coaching that supports players a century later.

In February 1909 Young, then 42, was traded by Boston to the Cleveland Naps for Charlie Chech, Jack Ryan, and $12,500 cash. Back in the city where he had started his big-league career 19 years before, Young enjoyed one more solid season, going 19-15 with a 2.26 ERA. The first time he faced the Red Sox, on May 13 in Cleveland, he lost 8-1 but his first game pitching again in Boston was a two-hitter on June 11, a 3-1 win. He might have won 20 but for an injury on September 10. He finished the season with 497 victories.

The following year, Young started only 20 games, finishing with a 7-10 record. He won number 499 with a two-hitter on June 30 (no runner reached second base), and booked number 500 on July 19. In that one he allowed one hit through the first eight, but it took 11 innings to wrap it up, a win over Washington. The Senators held a 2-0 lead through eight, but the Indians tied it in the ninth and scored three times in the 11th.

Young then won four more in a row, but after August 9 didn’t win any. He wasn’t used in the last several weeks of the season. Still, he resisted calls for him to retire from the game. “Quit the game, well, I guess not,” Young told a Cleveland reporter. “I’d be awfully lonesome, and you know this is a healthy game. I’ll not quit until I have to.”33

In 1911 the 44-year-old Young fared even worse, going 3-4 with a 3.88 ERA in seven starts before drawing his release on August 15. He was quickly picked up by the Boston Rustlers of the National League, who wanted him, according to one writer, “just to draw the crowd.”34 Young started 11 games for Boston down the stretch, going 4-5 with a 3.71 ERA. Despite much speculation that he would retire, Young attempted to hang on with the Rustlers (later the Braves) for the 1912 season, remaining with the team through spring training and warming the bench for the first month of the campaign. During spring training, Sporting Life had a little fun with Young’s longevity: “The old boy is said to look better than any previous season since 1663, considered by many to be his best years since the Summer of 1169.”35

But a chronically sore arm prevented Young from ever taking the field; when he attempted to do so, on May 23, he gave up after a brief warmup session, declaring, “It’s no use. I’m not going on. These poor fellows have lost too many games already.”36 Finally Young’s major-league career was officially over. He was 45 years old.

In 1913, the independent Federal League began play. The six-team league had franchises in Indianapolis, Cleveland, St. Louis, Chicago, Pittsburgh, and Covington, Kentucky. (The latter team relocated to Kansas City near the end of June.) Young managed the Cleveland Green Sox. They finished second, with a record of 64-54, 10 games behind Indianapolis. When the league reopened in 1914, it was as a third major league but Cleveland was not among the cities in the league.

In retirement, Cy returned to his home in Peoli, where he mostly lived out a quiet retirement on his farm, growing potatoes and tending to his sheep, hogs, and chickens. He and his wife, Robba, did not raise any children; the death of their only offspring, a daughter, a few hours after her birth in 1907, left, in the words of Young biographer Reed Browning, “an almost inexpungeable hole” in their lives.37 When Robba died in January 1933, a grieving Young sold his farm. “Somehow, after she died I didn’t want to live there anymore,” he said.38 Elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1937, Young was inducted with the Hall’s first class at the museum’s opening in 1939.

Despite his frugal habits and status as a baseball legend, Young was beset by financial problems late in life. In 1935 he traveled to Augusta, Georgia, where he joined a group of baseball veterans looking to make some money during the Great Depression by playing exhibition games. When this venture failed, Young returned to Ohio, where he found work as a clerk in a retail store in Newcomerstown and lived with a local couple, John and Ruth Benedum. He was invited to, and attended, reunions of old-timers around the country. He was still living with the Benedums when he died of a coronary occlusion on November 4, 1955, at the age of 88. He was buried in Peoli Cemetery. The next year, baseball instituted the pitching award that bears his name.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, Baseballhalloffame.org, and the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, as well as the Boston Globe, Boston Post, New York Times, and Washington Post.

The most indispensable source for Cy Young’s life and career is Reed Browning’s Cy Young: A Baseball Life (Amherst, Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Press, 2000).

Other sources:

Ivor-Campbell, Fred, ed. Baseball’s First Stars (Cleveland: SABR, 1996).

Masur, Louis P. Autumn Glory: Baseball’s First World Series (New York: Hill & Wang, 2003).

Notes

1 Reed Browning notes the difficulty in determining accurately the number of Young’s wins, suggesting that it may range from 508 to 513, but essentially agreeing that 511 is the number that researchers accept. Browning, 226-230.

2 We touch on these changes in the course of this brief biography.

3 Arthur Daley, Times at Bat: A Half-Century of Baseball (New York: Random House, 1950), 7.

4 This per a typed sheet in Young’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

5 Canton (Ohio) Repository, April 28, 1890, per Browning, 8.

6 Alvin K. Peterjohn, “First Year of Cyclone Young,” Baseball Research Journal 5, 1976: 83-89.

7 “Couldn’t Hit Young,” The Repository (Canton), July 26, 1890: 3.

8 Peterjohn. The sum of $300 is reported by Browning, 10.

9 Browning, 12.

10 “His Fists,” Cleveland Leader, June 20, 1896: 1.

11 “Young’s Record,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, September 19, 1897: 8.

12 Browning, 85-86.

13 Connie Mack, My 66 Years in the Big Leagues (Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, 2009), 91-92.

14 Sporting Life, July 18, 1891; quoted in Browning, 152.

15 Browning, 91.

16 His 192 wins for Boston remain a Red Sox franchise record, tied with Roger Clemens.

17 Unidentified newspaper clipping in Young’s Hall of Fame player file.

18 Sporting Life, August 2, 1902: 11.

19 Francis Richter, unidentified 1910 newspaper clipping in Young’s Hall of Fame player file.

20 “Baseball Coach Appointed,” Harvard Crimson, February 10, 1902.

21 Browning, 144.

22 The current record (59) is held by Orel Hershiser.

23 Browning, 144.

24 It was not a good year for baseball in Boston. The National League’s Boston Beaneaters (Braves) also won only 49 games, and lost 102.

25 “No Hit, No Run for ‘Yanks’ Off King Cy Young,” Boston Journal, July 1, 1908: 1.

26 Detroit Tribune, quoted in “Cy Young’s Life Is Simple Story,” Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette, December 27, 1904: 7.

27 Alfred Henry Spink, The National Game: A History of Baseball, America’s Leading Out-door Sport,From the Time It Was First Played Up to the Present Day, with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches (St. Louis: National Game Publishing Co, 1911), 166.

28 Browning, 97.

29 There were reports that both Lou Criger and Young had rebuffed very lucrative offers to throw games in the 1903 World Series. See Browning, 137-140.

30 Sporting Life, November 25, 1893.

31 Browning, 226.

32 Unidentified newspaper clipping in Young’s Hall of Fame player file.

33 Cleveland Leader, August 21, 1910: 3, 1.

34 “Murnane Musings,” Tim Murnane, The Sporting News, August 31, 1911: 3.

35 “National League News in Short Metre,” Sporting Life, March 16, 1912: 11.

36 Arthur D. Hittner, Honus Wagner: The Life of Baseball’s “Flying Dutchman” (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1996), 212. Hittner was quoting the Pittsburgh Gazette Times.

37 Browning, 171. The baby girl’s name, if indeed one had been chosen, did not appear in newspapers.

38 Browning found Young’s remark in an unidentified clipping from 1944 in the Cy Young player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame. More easily done in years gone by, there were apparently some impostors, or fanciful stories. A 1909 article in the Oklahoma City Daily Oklahoman reported the marriage of Miss Annie Dechman (“one of Oklahoma City’s really popular society belles”) to “well-known baseball pitcher” Cy Young. The newspaper did report skeptical reaction to the news from Dechman’s friends: “It didn’t sound probable, not even possible.” Nonetheless, the young bride and whoever else was on the telephone both confirmed it. See “Young Wedding Is All a Surprise,” Daily Oklahoman, November 20, 1909: 8.

Full Name

Denton True Young

Born

March 29, 1867 at Gilmore, OH (USA)

Died

November 4, 1955 at Newcomerstown, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.