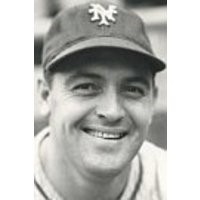

Ace Adams

By the time Ace Adams was born, his parents may have run out of names, because he was their eighth child. For whatever reason, they named the baby after a family friend, Ace Townsend. Many men named Adams have been called Ace, including a rapper/record producer and a pitching coach, but Ace Townsend Adams appears to be the first one who was given the name at birth.

By the time Ace Adams was born, his parents may have run out of names, because he was their eighth child. For whatever reason, they named the baby after a family friend, Ace Townsend. Many men named Adams have been called Ace, including a rapper/record producer and a pitching coach, but Ace Townsend Adams appears to be the first one who was given the name at birth.

The real-life Ace grew up to be the relief ace of the New York Giants during World War II. One of the first iron-man relievers, the right-hander worked more than 60 games for four straight years — no one else had done that even twice in a row — and pitched a record 70 times in 1943. But he wasn’t happy about it. “You couldn’t make any money relieving,” he complained. “Relieving was the low dog.”1

Adams ended his major-league career abruptly when he jumped to the Mexican League in 1946. He never expressed any regret. He said the Mexicans gave him 50,000 reasons not to.

Adams was born in Willows, California, on March 2, 1910, to the former Emma Jane Nichols and Walter Scott Adams. He grew up on a fruit farm in the Northern California mountains.

The boy earned a local reputation as a pitcher, catcher, and boxer. While still a teenager, he married his first wife, Ethel, and they named their son Ace. Adams moved to San Francisco to take a job pitching for the El Rey brewery team. Between games he poured free beer for visitors to the plant. When a Brooklyn scout signed him in 1934, he was 24 years old but subtracted two years from his age.

Assigned to the Class-D Evangeline League, Adams stalled in Louisiana for three years despite winning 16 games and then 20 while twice leading the league in strikeouts. Some scouts thought he was too small at 5-feet-10½, even though he was a blocky 180 pounds. Getting nowhere, he decided to quit the game. But his manager at Jeanerette, Emmett Lipscomb, persuaded him to come along to Cordele, Georgia, in the Georgia-Florida League, another Class-D circuit.

By this time Ace and Ethel had divorced. He met his second wife, Ellie Hornsby, in Cordele. Ace bought a 180-acre farm near the crossroads hamlet of Iron City, acquired a passable drawl, and lived in Southwest Georgia for the rest of his life.

Adams won 26 games for Cordele in 1937, plus two more in the playoffs, and began to move up. He led the Class A-1 Southern Association in strikeouts in 1940, despite missing some time after he was hit on the wrist by a line drive. He helped Nashville win the pennant and the Dixie Series with two victories over Texas League champion Houston. When the Vols arrived home from Houston, Ellie met the train waving a newspaper with the headline “Adams Sold to Giants.”2

Reaching the majors after a seven-year slog through the bushes, he erased another two years from the calendar. He was listed as 27 instead of 31. Taking some of the edge off his thrill, he learned that the Giants expected him to live in New York on $2,500 a year.

On Opening Day in 1941, Adams sat on the bench at Ebbets Field enjoying the first big-league game he had ever seen. When the Giants fell behind the archrival Dodgers, manager Bill Terry let the rookie get his feet wet. He pitched the last three innings, allowing only one hit, and was rewarded when the Giants rallied to win. Terry “picked me up on his shoulders, carried me off and gave me a thousand dollar raise before we got to the clubhouse,” Adams recalled.3

Terry thought he had found a relief pitcher, willing or not. Adams got into 38 games, more than any other Giants reliever, with a 4-1 record but an unsightly 4.82 ERA.

Adams’ fastball didn’t scare anybody. He threw a little of everything — including some pitches he didn’t talk about — changing speeds on his breaking stuff and recording few strikeouts. “I would mix the rosin and Beech-Nut tobacco juice,” he said. “Chewing tobacco and rosin. You could lick your fingers like that and when you got those two together you could throw a pretty good curve ball. That was legal.”4 He had been working on a slider since a Nashville teammate showed him how to throw it, but didn’t get the hang of it until 1942. It turned him into an outstanding big-league pitcher.

A new manager, Mel Ott, began using Adams primarily to finish games. Adams led the league in that category for the next four seasons. He usually pitched just an inning or two — only 88 in 1942 — but his role was unlike the modern closer’s. He was a true fireman, often called in with runners on base, no matter whether the Giants were ahead or behind. His 61 appearances equaled the major-league record for relief games set by Clint Brown of the White Sox three years earlier.

Adams’ 1.84 ERA was his career best. Although 1942 was the first wartime year, most major leaguers were still on the field. Adams was not pitching against the replacements who would populate the rosters for the next three seasons.

He put up a 7-4 record with 11 saves. Of course, nobody knew he saved 11 games. “We couldn’t bargain with saves when it came time to talk contract because there was no such thing back then,” he said years later. “That’s why I didn’t like the relief.”5 But he did not labor in obscurity. His chase of the record was big news, more so because he broke the National League mark of 56 games pitched (at the 60’6” distance) that was shared by the sainted Giant Christy Mathewson.

After a third-place finish in 1942, the Giants collapsed the next year. The military took three of their leading hitters, Johnny Mize, Harry Danning, and Willard Marshall. Player-manager Ott showed his age at 34 and hit only 18 home runs, about half his usual production. The club’s best pitcher, Hal Schumacher, also went into the service. Carl Hubbell was finished at 40, and the rest of the pitchers stunk up the Polo Grounds, except for Adams and his pal Cliff Melton. The Giants lost 98 games and finished last for the first time since 1915.

The league’s worst pitching staff completed only 35 starts, leaving plenty of work for the bullpen. Ott tested how far Adams’ rubber arm would stretch. Adams pitched in 30 of the club’s first 57 games. He was beginning to show the strain, blowing three of his last four save opportunities.

Ott continued to call his number. The alternatives were not appetizing. Adams pitched on back-to-back days 20 times, although he worked three days in a row only once. He pitched in both ends of a doubleheader 10 times. He was a show horse as well as a workhorse. He reeled off 27 consecutive scoreless innings in May and blew just one save after June 20, only four all season.

Adams pitched the longest outing of his career, 9 2/3 innings in relief, on September 4 before losing to Brooklyn in the 17th. He never stopped pestering the manager to give him a chance to start. With the season down the drain, Ott must have figured, “What the hell. At least it will shut him up.” Ott promised Adams a start in a Sunday doubleheader against the Boston Braves on September 12.

But on the Wednesday before that, Ott called on him in the eighth with the Giants trailing Philadelphia by just one run. Adams worked the last two innings in his 62nd appearance, breaking his and Brown’s record for games in relief.

On Saturday the 11th, the Giants and Braves went into extra innings tied 3-3. Ott brought in Adams to pitch the 10th. And the 11th, 12th, and 13th before Mickey Witek won the game for him with a walk-off homer.

“Ott said, ‘It looks like you can’t start tomorrow.’ I said, ‘The heck I won’t.’”6

After 162 relief appearances, and no day off, Adams took the mound for his first career start in the second game of the Sunday doubleheader. All he did was limit the Braves to one hit in eight innings while the Giants staked him to a 7-0 lead. He yielded two meaningless runs in the ninth before he finished the three-hitter with a strikeout.

“The next day they called me into the office and said, ‘If we double your salary, will you relieve for us?’ I said, ‘I’ll relieve, and I’ll be the batboy, too.’”7

Adams pitched for the 65th time when he relieved on September 15. His next appearance would match the major-league record of 66 games in a season by Ed Walsh in 1908. The spitballer Walsh was a starter who also worked in relief.

Ott decided to let Adams tie the record as a starter. He lasted six innings against Brooklyn, giving up two runs, and was the winning pitcher. Ott gave him another start to break the record on September 27. This time the Cubs knocked him out in the fifth. He got no decision, but he wrote his name in the record books.

Adams appeared three more times in relief to raise his mark to 70 games pitched.8 He worked 140 1/3 innings, won 11, lost 7, and saved 9 with a 2.82 ERA. Now here’s the weird part: Another reliever, Cincinnati’s Clyde Shoun, finished far ahead of him in the Most Valuable Player voting, 24 points (10th place) to 7. Why? Shoun won 14 games and posted the league’s best winning percentage, .737. That made him a more valuable pitcher in the eyes of 1940s sportswriters. In 45 games, Shoun earned seven saves, but blew five opportunities.

As a married father, Adams had been exempt from military service. With draft calls growing, he took a physical and was classified 4-F, unfit for service, because of an old knee injury. He pitched through the war as the majority of big leaguers were called up, to be replaced by the old, the young, and the infirm.

Ott gave Adams a shot at a regular starting job in 1944. He beat the Dodgers in his first outing, allowing just two runs in a complete game. But his next three starts were disasters: 13 runs in 14 1/3 innings. Back to the bullpen for good.

His 65 appearances led the league for the third straight year and he led in saves for the first time with 13. But his effectiveness slipped. His ERA in relief jumped to 3.94, and he blew five save opportunities, finishing with an 8-11 record in 137 2/3 innings. Ernie Lombardi, winding up his career as the Giants’ wartime catcher, caught one of Adams’ fastballs barehanded. “I was hot,” Adams recalled. “I said, ‘What the hell are you trying to do, you big son of a gun, showing me up like that! … Yeah, he could have at least rubbed and let the fans know I had something.”9

Adams opened the 1945 season by holding opponents scoreless in nine of his first 10 appearances. But he was 35 years old, a fact he kept to himself, and his performance soon turned erratic. Ott began easing his workload, seldom using him on consecutive days. Again pitching 65 games, this time he accumulated only 113 innings. His ERA improved to 3.42, with an 11-9 record. His 15 saves tied for the major-league lead, but he blew eight chances.

When the genuine big leaguers came home from military service in 1946, most wartime replacements were quickly shunted aside. Adams had no reason to fear for his job because the Giants had no proven relief pitchers returning. On Opening Day he made his 300th career appearance, working one shutout inning, but he was hit hard in his next two games. On April 24 the Braves greeted him with a walk and a double, then Tommy Holmes slammed a home run, chasing Adams off the mound before he got anybody out. Holmes was the last batter he faced in the majors.

Recruiters from the Mexican League had been prowling the spring training camps, waving gobs of cash. They struck out with the big stars, but lured some mid-level players. Seven Giants, including pitcher Sal Maglie and outfielder Danny Gardella, had already gone south. The Mexicans offered to better Adams’ $9,000 salary. On April 26 he and fellow pitcher Harry Feldman went to the Polo Grounds, packed their gear, and took off. Commissioner Happy Chandler had decreed that the Mexican League “jumpers” would be suspended for five years, so the 36-year-old Adams knew he was walking away for good.

He said the Mexicans gave him a $50,000 contract. “That was pretty hard to turn down then, all expenses paid, an apartment. Fifty thousand in 1946 for five months work. That’s all I can save in five years. I was about to retire anyway, why not take it?”10

In other interviews, Adams said $50,000 was the total for a three-year contract. At nearly $17,000 a year, that would be more than the salaries paid to the most prominent jumpers, All-Stars Mickey Owen of the Dodgers and Vern Stephens of the Browns. Owen told historian William Marshall that he signed for five years at $15,000 a year, plus a $12,500 bonus. Stephens said he was promised the same salary.11

When Adams and Feldman left the Giants, the New York Times reported that each had received a $10,000 bonus and $10,000 salary from the Mexicans.12 Even $20,000 up front was more than double Adams’ paycheck from the Giants. “Adams, in particular, felt that he was nearing the end of his career,” Giants secretary Eddie Brannick said, “and wanted to get the dough while the getting was good.”13

The US players found Mexican ballparks primitive, with no clubhouses or showers. Games in one park had to stop when a train chugged across the outfield. Some players got sick from the food and water. Stephens turned around and came home before Opening Day, avoiding a suspension. Owen wanted to return, but Dodgers president Branch Rickey wouldn’t take him back.

Many of the imported players were expensive disappointments, especially the pitchers, whose curve balls straightened out at high altitude. Adams, pitching for Veracruz, compiled a 5-7 record and 4.09 ERA.14 League president Jorge Pasquel dumped most of the big salaries after the season. Adams heard nothing from Pasquel about playing again in 1947. In the spring he told writer Furman Bisher, “I’m tickled pink not to have to return. It’s strictly second-rate.”15

Adams remembered the experience differently in later years. “My wife went along down there with me and we had a nice year,” he said in 1990. … “[W]e went first class, train and plane. No buses, and it wasn’t bad at all.”16 With those comments, and his insistence that he was paid $50,000, he may have been covering up his embarrassment over making a mistake. But he felt no loyalty to major-league baseball: “They owned you like a mule.”17

While some of the Mexican jumpers suffered financially during their suspensions, Adams had his Georgia farm to fall back on. He reportedly owned more than 500 acres planted in peanuts, cotton, and corn. When Gardella and others sued baseball for reinstatement, Adams did not join them. But he still felt the sting of the suspension: “Being on the blacklist is sorta like being a criminal. If I could only get that lifted. It’ll hang over my head and folks won’t remember me for my National League records, only as the guy who was banned for five years because he went to Mexico.”18

His outlaw status hit home when the Dixie Lily flour company hired him to coach its team. “I was coaching a little semipro team down in Florida,” he said, “and they sent somebody out on the field and said that I couldn’t coach, took me off the field.” He filed his own lawsuit and said he collected a settlement from baseball.19

In June 1949 Commissioner Chandler declared amnesty for the 18 Mexican League defectors because major league owners were afraid to test their reserve clause in court. Adams, now 39, did not try to come back.

He returned to Organized Baseball as an owner in 1952 when boosters in Fitzgerald, Georgia, essentially gave him their failing Class-D club. He managed and tried to pitch, but his arm was gone. In June President Adams fired manager Adams.20

Ace, Ellie, and their son Alvin and daughter Cindy moved to the nearby town of Albany in 1953. He opened a liquor store and later owned Ace’s Oyster Bar next door, another restaurant, an Amoco service station, and a monument company.21 Alvin eventually took over the businesses, but Ace continued to work part-time at the liquor store into his 80s. When a visitor asked him to sign a baseball, he said, “You better be careful, I’m likely to take my ring and cut this thing. Force of habit!”22

Adams died at 95 on February 26, 2006. In addition to the children and grandchildren from his second marriage, his family included a son, grandson, great-grandson, and great-great-grandson, all named Ace.23

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Additional sources

Lieb, Frederick G. “Ace Adams, His Barrel Overflowing, Keeps Tossing That Apple As Majors’ Relief Marvel.” The Sporting News, September 10, 1942.

Smith, Ken. “Rookie Adams, Once a Pro Boxer, Tossed into Ring by Bill Terry As Late-Round Box Stopper for Giants.” The Sporting News, June 5, 1941.

Notes

1 Ace Adams interview by Brent Kelley, September 27, 1991, in the SABR Oral History Committee collection.

2 Ibid.

3 Bob Cairns, Pen Men (New York: St. Martins, 1992), 49.

4 Ibid., 48.

5 Ibid., 51.

6 Mike Eisenbath, “Pioneer Closers Didn’t Require Much ‘Down Time,’” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 12, 1990: 4F.

7 Ibid.

8 Adams’ record stood for just six years, until the Phillies’ Jim Konstanty pitched in 74 games in 1950. Nobody passed Konstanty until 1964.

9 Cairns, Pen Men, 51.

10 Ibid., 54.

11 William Marshall, Baseball’s Pivotal Era, 1945-1951 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1999), 50, 53.

12 “Feldman and Adams Quit Giants,” New York Times, April 27, 1946: 20.

13 Associated Press, “Ace Adams, Feldman Jump Giants for Mexican League,” Rochester (New York) Democrat and Chronicle, April 27, 1946: 16.

14 Statistics provided by Rory Costello from Pedro Treto Cisneros, editor, Enciclopedia del Beisbol Mexicano (Mexico City: Revistas Deportivas, S.A. de C.V.: 11th edition, 2011).

15 Furman Bisher, “Ace Living Like a King on Farm, With Only One Regret—His Ban,” The Sporting News, May 7, 1947: 24.

16 Cairns, Pen Men, 54.

17 Kelley interview.

18 Bisher, “Ace Living Like a King.”

19 Cairns, Pen Men, 55.

20 Associated Press, “Adams, Ex-Relief Ace, Fires Himself,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 13, 1952: 48.

21 “Ace Townsend Adams,” Albany (Georgia) Herald, March 4, 2006: 6B. Obituary provided by Laura Elliott of the Dougherty County Public Library.

22 Cairns, Pen Men, 47.

23 Stephen Miller, “Ace Adams, 95, Giants Pitcher of the 1940s,” New York Sun, March 10, 2006. http://www.nysun.com/obituaries/ace-adams-95-giants-pitcher-of-the-1940s/28677/, accessed January 22, 2018.

Full Name

Ace Townsend Adams

Born

March 2, 1910 at Willows, CA (USA)

Died

February 26, 2006 at Albany, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.