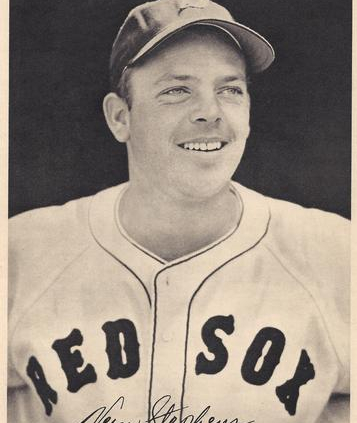

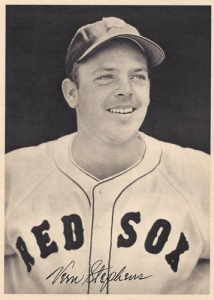

Vern Stephens

The 1940s witnessed a special group of major league shortstops, including the likes of Lou Boudreau, Phil Rizzuto, Marty Marion, Pee Wee Reese and Johnny Pesky. During his own career, Vern “Junior” Stephens was considered to be as good or better than any of his illustrious peers, yet within a few years after his retirement, he had been largely forgotten, remembered mostly as a plodding one-dimensional slugger. He was much more than that. Yes, he was a three time RBI champion, but he was also a fine fielding shortstop, an eight-time all star, and a very popular teammate on some of the era’s most successful teams. History ought to remember him.

The 1940s witnessed a special group of major league shortstops, including the likes of Lou Boudreau, Phil Rizzuto, Marty Marion, Pee Wee Reese and Johnny Pesky. During his own career, Vern “Junior” Stephens was considered to be as good or better than any of his illustrious peers, yet within a few years after his retirement, he had been largely forgotten, remembered mostly as a plodding one-dimensional slugger. He was much more than that. Yes, he was a three time RBI champion, but he was also a fine fielding shortstop, an eight-time all star, and a very popular teammate on some of the era’s most successful teams. History ought to remember him.

Vernon Decatur Stephens Jr. was born on October 23, 1920 in McAlister, New Mexico, to Vernon Sr. and the former Grace McMullen. Vern Sr. was born in the Oklahoma territory, and was a farmer in Ft. Smith, Arkansas when he met his future wife, Grace, a schoolteacher and devout Southern Baptist. They soon married, and in 1920, with a one-year-old son, Harry, and a second on the way, Vernon and Grace decided to resettle in the west. They had gotten as far as New Mexico when Vern was born prematurely. The Stephens family eventually settled in Long Beach, California.

Vern Sr., or “Pop,” landed a job as a supervisor at a local dairy, which got him out of bed at 3:30 AM but also gave him ample opportunity to play basketball and baseball with his sons when he got home. (Later Pop umpired for several years in the minor leagues.) Harry and Vern played baseball passionately as children. Harry, a pitcher, later signed a contract with the Browns, but hurt his arm before reporting to the minor leagues and never pitched again.

Vern entered American Legion baseball at age 13, and played shortstop on the 1936 Southern California champions. One teammate was Bob Lemon, later a star pitcher for the Cleveland Indians, who remained a close friend for the rest of Vern’s life. Stephens went to Long Beach Polytechnic High School, while Lemon was across town at Wilson High School. Vern’s high school teammates included future major leaguers Chuck Stevens and Bobby Sturgeon. Vern was a natural athlete-he also played basketball and swam-but he was quite small (5′ 5″ and 120 pounds) in high school. In his late teens, he grew to 5′ 10″, and ended up a powerful 185 pounds. Vern attributed his upper body strength to his swimming.

Vern was a very good student in high school-receiving all A’s and B’s-thanks largely to his mother, the former teacher, who tutored both of her sons after school. After graduating from high school in 1937, Vern attended Long Beach Junior College for a year and hit .522 for their baseball team. There he met Harriet Bernice Hood, who had dated Bob Lemon in high school. Vern and Bernice (she disliked the name Harriet, and never used it) were soon constantly together, and they married in 1940.

After his one junior college season, Stephens signed with the St. Louis Browns for a $500 bonus. The Red Sox and Indians also expressed interest, but Vern’s father saw a quicker path to the majors with the lowly Browns. Vern played sparingly at two minor league stops-first Springfield (Illinois) of the Class B Three-I League and then Johnstown (Pennsylvania) of the Class C Middle Atlantic League-in 1938.

The next year he dominated the Kitty League with Mayfield (Kentucky), leading the circuit with 123 RBI and a .361 batting average while hitting 30 home runs. After another RBI title with San Antonio of the Texas League in 1940, manager Marty McManus, a former big league shortstop himself, called Stephens the “best shortstop prospect I have ever seen.” One more excellent minor league season, with Toledo of the American Association (14 home runs, .281), earned him a recall late in 1941 and a shot at a job with the Browns the following spring.

However, predictions for his stardom were hardly unanimous. His Toledo manager, Fred Haney, supposedly told Browns skipper Luke Sewell that “Stephens will never play shortstop in the major leagues as long as he has a hole in his ass.” By the middle of spring training, Sewell had come to disagree, saying, “That kid out there is going to be the kingpin of our defense-and if he comes through as a hitter we’re going to cause a lot of trouble this summer.”

He came through as a hitter. As a rookie Stephens batted .294 with 14 home runs and 92 RBI, as the Browns achieved their best record in 20 years. Stephens finished fourth in the 1942 MVP balloting, one slot behind fellow rookie shortstop Johnny Pesky of Boston. He led the league with 42 errors, but contemporary accounts make no mention of his defense being a problem. He was only 21, and one of the bright young stars in baseball.

A strong man with a powerful upper body, Stephens did not look like a shortstop. If he had less range than some of his slighter contemporaries, he could play deeper because of his great throwing arm. A right-handed hitter, he had a spread stance, slightly open, and stood deep in the batter’s box.

In early 1943, Stephens re-aggravated a knee he had hurt in the minor leagues, causing him to flunk his army physical. The injury caused the Browns to consider moving him to the outfield, where they used him eleven times. At the plate he turned in another fine year -22 home runs, 91 RBI and a .289 average. The Browns slipped from third to seventh place, but Stephens still finished ninth in the MVP balloting. Later reclassified as 1-A, he failed the exam again in 1944 and became one of the better players to remain in the major leagues through the entire war. During off-seasons he worked at a shipyard in Long Beach.

Although his friends and family had always called him Vern or Vernie, he was often referred to as Junior in baseball circles. To confuse things further, his close friends in baseball called him Steve or Stevie.

In 1944 Stephens led his team to its first and only American League pennant, hitting .293 with 22 home runs and 109 RBI. He moved up to third in the MVP vote behind Detroit pitchers Hal Newhouser and Dizzy Trout, who combined to win 56 games. In both 1943 and 1944 Stephens played all nine innings and batted fourth for the American League in the All-Star game. He was the best player on the best team, and he was just turning 24.

In William Mead’s classic book on wartime baseball, Even the Browns, he quotes several Browns teammates who were seemingly in awe of Stephens. Mark Christman, the team’s third baseman, considered Stephens to be as good a shortstop as Cardinals’ star Marty Marion: “not as good hands, but he covered as much ground, and he had an arm like a shotgun.” Christman also marveled at Stephens’ strength, noting that although he played at Sportsman’s Park, a tough park for a right-handed hitter, Stephens could hit the ball the other way onto the pavilion roof in right-center.

A few of his Browns teammates remember Stephens as a considerable partier. Don Gutteridge, his roommate, marveled at “how he did it-go out like he did and then play as well as he did. He was superman.” In 1945 he had another carbon copy season-89 RBI, a .289 average and a league leading 24 home runs. The Browns dropped to third place, but Stephens continued to impress the MVP voters, finishing sixth.

After the 1945 season, the reigning home run champ thought he deserved a decent raise from his struggling ballclub. Stephens asked for $17,500, while the Browns offered only $13,000. Rather than reporting to spring training, Stephens decided to hold out in Long Beach and learn to play golf. The Red Sox offered to deal Johnny Pesky, who had spent the last three seasons in the army, and cash to the Browns for Stephens. Manager Luke Sewell vetoed the deal because “Stephens has a stronger arm. He’ll throw out more men from the hole. I guess we’ll hold on to him.”

In the spring of 1946 baseball was jolted by unexpected competition from south of the border. While operating outside the sphere of organized baseball, the Mexican League had been in operation since 1924, never posing a threat to the major leagues. In 1946 this suddenly changed, as industrialist Jorge Pasquel, who was president of the league and also owned two teams, began offering large contracts to the biggest stars in the game, among them Ted Williams, Bob Feller and Stan Musial. Several quality players, including Mickey Owen and Max Lanier, jumped to the rebel circuit.

Pasquel called the disgruntled Stephens nearly every day for two weeks, before Vern finally decided that the Mexican League could offer him some leverage. In late March, commissioner Happy Chandler announced that all players who did not return to the United States within ten days would be banned from organized baseball for five years. When Pasquel called the next day, Stephens asked for a five-year $175,000 contract, with all the money up front. He also insisted that he be allowed to break the contract at any time. Pasquel said yes.

The next day Stephens was in Mexico City living at the Pasquel mansion. Stephens had $5,000 sent home to Bernice in Long Beach, and the balance put in a local bank. “They couldn’t do enough for me,” Stephens later told writer Al Hirshberg. “From the time I got to Mexico until the time I left, they were wonderful to me.” Stephens played two games for the Veracruz Blues, recording one hit in eight at bats.

Within a few days, Stephens was ready to return to the States. Though he never had a bad word to say of his hosts, he later claimed he never intended to stay long-he was just trying to get more money out of the Browns. His father, who could not watch Vern throw his career away, drove with Browns’ scout Jack Fournier to Monterrey (where the Blues were playing), found his son, put him in the car, and drove him back over the border. Stephens returned all of the money to Pasquel.

Stephens promptly returned to the Browns, getting back to the United States within Chandler’s ten-day deadline. Best of all, the Browns gave Stephens a contract for $17,500, exactly what he had asked for.

In 1946 all of the stars returned from the war, and many observers assumed that Stephens’ star would dim. He missed 39 games with assorted injuries that made his power (14 homeruns and 64 RBI, both league highs for shortstops) seem to have slipped, but he hit a career high .307. In 1947, he had another pretty good year with the bat (15 homeruns, 83 RBI, and a .279 average). He turned 27 that October and was rightly considered one of the best players-offensively and defensively-in baseball.

The Browns, on the other hand, had fallen into dire straits. In 1947 ownership spent two million dollars to buy and renovate Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis and to build a new facility for their San Antonio farm club. After drawing only 320,000 fans and finishing last, the Browns had to sell players to recover their huge losses. The demand for Stephens, their best player, was high. The Cleveland Indians were prepared to trade Lou Boudreau and cash for him, but when the story was leaked, Indians fans picketed Cleveland Stadium. Newspapers printed ballots asking fans to vote on the trade of their beloved player-manager, and the result was a landslide for keeping Boudreau. Owner Bill Veeck had promised to abide by the will of the people, so the trade collapsed. In the event, Boudreau was the league’s 1948 MVP and led his team to a World Series title.

The Boston Red Sox had long coveted Stephens. They had missed signing him in 1938, and had been trying to trade for him every year since he reached the major leagues. Taking advantage of the Browns struggles, the Red Sox finally got their man, forking over eight players and $385,000 for Stephens, Ellis Kinder, Jack Kramer, and Billy Hitchcock. The deal, announced in two pieces on consecutive days in November 1947, was one of the largest transactions yet consummated.

The Boston press corps was skeptical. Tom Yawkey had purchased the team in 1933 and had spent millions acquiring name players, such as Lefty Grove and Jimmy Foxx, without contending for a pennant. Only when this strategy was abandoned in favor of investing in young talent, such as Ted Williams, Bobby Doerr and Dom DiMaggio, did Boston begin to see competitive teams every year. Stephens was an acknowledged star, all agreed, but a temperamental one who battled management every year for more money.

Not only that, but the Red Sox already had an All-Star shortstop in the popular Pesky, a lifetime .330 hitter who had surpassed 200 hits in his each of his first three major league seasons. The deal was seen as another example of the Red Sox needlessly throwing money around.

The Red Sox also had a brand new manager, Joe McCarthy, who had won seven World Series titles with the New York Yankees. The most interesting dilemma facing McCarthy in the spring of 1948 was which of his star shortstops he would move the third base. The prevalent thinking was that he would move Stephens, a powerfully built man who looked less like a shortstop than the slight Pesky. McCarthy did not announce his intentions until spring training in Sarasota, when he moved Pesky to the hot corner.

In a June 1948 story in Sport magazine, Harold Kaese wrote of the great relationship between Stephens and his teammates, and that Stephens had “won the battle” for the position because he was one of the best fielding shortstops in baseball. Stephens’ defensive statistics were very good, and McCarthy was undoubtedly aware of Stephens’ great range and arm. Vern had led the league in assists in 1947, and would again in 1948 and 1949. In the same article, Bobby Doerr said: “[Stephens is] nice to work with like Pesky. They co-operate on pop flies in the sun, and work with you on other plays. Perhaps the best thing that impresses me about Vern is the speed with which he goes across the bag on double plays.” In a story written just after Stephens died in 1968, Johnny Pesky said: “I always believed McCarthy did it because Stevie had such a great arm.”

In 1948, playing in a friendlier park for his skills and hitting behind several great table setters, Stephens hit 29 home runs and drove in 137 (second in the league to Joe DiMaggio). Though his batting average fell to a career low .269, he established a new high with 77 walks. He finished fourth in the balloting for MVP, behind Boudreau, DiMaggio, and Ted Williams. After several weeks of experimentation, McCarthy eventually settled on Stephens to hit cleanup behind Williams, and that’s where he would hit for the remainder of his years in Boston. The Red Sox improved from 83 to 96 wins, but lost a one-game playoff for the pennant to the Indians.

In 1949 Stephens slugged a career-high 39 home runs, a record for shortstops later broken by Ernie Banks, and drove in a 159 runs, a total not surpassed in the major leagues for 50 years, when Cleveland’s Manny Ramirez totaled 165 RBI in 1999. He also batted .290 and walked a career high 101 times. Despite great years from several other players, the Red Sox lost a great pennant race on the last day of the season to the Yankees.

At about this point the baseball media began to turn its back on Stephens. The reasoning is not hard to discern: Stephens was putting up great statistics every year, but the Red Sox were still finishing second. He received one first place vote in the MVP balloting and finished seventh, surprisingly low considering his historic year. In 1950 Stephens hit 30 home runs, led the league with 144 RBI and hit .290. Nevertheless, he finished 25th in the MVP balloting, behind six of his teammates. It is hard to fathom how a shortstop could lead the league in RBIs and be considered the seventh-best player on his own club.

One of the knocks on Stephens was that he was a good hitter who was lucky to play in Fenway Park. While the ballpark helped his statistics, from 1948 through 1950 he averaged 15 home runs and 67 RBIs on the road. A shortstop who hits like that in half of his games, walks 80 times a year, plays good defense, gets along with his teammates and manager, and stays healthy-this was basically Stephens for ten years.

Halberstam writes of an encounter that supposedly occurred between Williams and Yankee pitcher Allie Reynolds at an All-Star game. Williams jokingly asked when Reynolds was going to start giving him some good pitches to hit. Reynolds countered with words to the effect “not as long as Stephens is hitting behind you.” Vic Raschi told Halberstam that Stephens could be pitched to by throwing fastballs high and away, but that Doerr (who followed Stephens in the batting order) was as good a hitter as the Red Sox had and required extreme care.

Actually, Stephens was a fairly patient hitter who walked 101 times in 1949, the base year for Halberstam’s book. Also, Stephens drove in 159 runs, and hit very well against the Yankees. From 1948 through 1950, Stephens had 13 home runs against New York-including four off Raschi himself-and drove in 54 runs, totals in line with his great statistics in those years.

When pitchers were interviewed about Stephens when he was playing, they generally provided a glowing description. In an article in the Fall 1951 issue of Complete Baseball, Ed Rummill quotes Ed Lopat on Stephens: “He’s tough, real tough … if you throw one to the outside corner, he’s liable to hit it down the right field line for two or three bases.” Ned Garver told the same writer: “That Stephens gives me as much trouble as the rest of the Red Sox combined.” Jack Kramer was just as positive: “Stephens is as strong as Foxx ever was. I’m convinced of it.”

Following the 1950 season, the Red Sox acquired yet another shortstop, their 1948 nemesis, Lou Boudreau. New manager Steve O’Neill moved Stephens to third and divided the time at shortstop between Pesky and Boudreau. Unfortunately, Stephens aggravated his old knee injury and played only 91 games in the field. In only 377 at bats, he hit .300 with 17 home runs, and 78 RBI-production consistent with the previous three seasons.

He declined fairly rapidly thereafter. Following another injury-laden year in Boston, he moved on to the White Sox, the Browns, and the Orioles for three mediocre seasons. After 1950, when he turned 30, he never again played more than 101 games or hit more than eight home runs. In mid-1955, he signed with the Seattle Rainiers of the Pacific Coast League, where he played through the end of the 1956 season.

There are two theories as to his sudden decline. One suggests that he was never able to recover from his knee injury, which disabled him in both 1951 and 1952. Fifty years ago a bad knee could be devastating to an infielder in his early 30s. According to his son, Vernon III, his eyes also started to fail him about this time.

The other theory is that his nightlife finally caught up with him. Although some of his old Browns’ teammates marveled at his after-hours activities, Boston roommate Johnny Pesky downplayed his reputation as a partier, suggesting that this was no longer going on while he was in Boston. Before his knee injury in 1951, Stephens was remarkably durable-he did not miss a single game in 1948 or 1949 and missed ten or fewer several other times.

Stephens was just thirty-five when his baseball career ended. His post-career passion was golf, which he had taken up during his holdout in 1946. He was breaking 100 as a beginner, largely because of his long, powerful drives. Within a few years he was regularly scoring in the low 70s-a scratch golfer. He was one of the best amateurs in California for many years after leaving baseball, and played in many Pro-Ams, including the Bing Crosby National at Pebble Beach.

Vern and Bernice had three children: Vernon III, Ronald, and Wendy. Although the couple met many people during his years in the game, many of their closest friends remained the people they had known back in their school days. Chuck Stevens, Bob Lemon, Bobby Sturgeon and their wives all returned to Long Beach during the off-seasons and after their careers finished, and they all socialized regularly.

Stephens was a sales representative for Hillerich & Bradsby for a while, which afforded him free golf equipment. He also worked in sales for Owl, a trucking and construction company, and then for the Bechtel Corporation. On November 3, 1968, at work, he had a heart attack lifting a piece of machinery. He was rushed to the hospital, where he died several hours later. He was just 48, and still golfing several times a week.

Sources

In preparing this article, I was able to interview Vern Stephens’ eldest son, Vernon III, as well as his lifelong friend and teammate, Chuck Stevens, both of whom were delightfully cordial and helpful. David Vincent provided Stephens’ record from SABR’s Tattersall/McConnell home run log. David Smith sent me Stephens’ game-by-game data sheets for the seasons 1948-50. I obtained a copy of Stephens’ file from the Hall of Fame library in Cooperstown, NY.

In addition, I made use of the following sources:

Devine, Tommy. Fugitive from Futility, in “Baseball Stars of 1950,” [Bob Considine ed.], Lion Books, 1950.

Halberstam, David. Summer of ’49 . Morrow, 1989.

Hirshberg, Al. “Vern Stephens-Junior Red Socker”. Sport. August 1949.

James, Bill. The Politics of Glory. Macmillan, 1994.

Kaese, Harold. “A Little Slug for the Red Sox”. Sport. June 1950.

Kaiser, David. Epic Season. University of Massachusetts, 1998.

Mead, William. Even The Browns. Contemporary Books, 1978.

Rummill, Ed. “The Man Behind Williams”. Complete Baseball. Fall 1951.

Stout, Glenn and Richard Johnson. Red Sox Century: One Hundred Years of Red Sox Baseball. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2000.

Williams, Ted and John Underwood. My Turn At Bat. Simon and Shuster, 1969.

Waldman, Frank. Famous Athletes of Today, Eleventh Edition. L.C. Page and Company, 1950.

Photo Credit

The Topps Company

Full Name

Vernon Decatur Stephens

Born

October 23, 1920 at McAllister, NM (USA)

Died

November 4, 1968 at Long Beach, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.