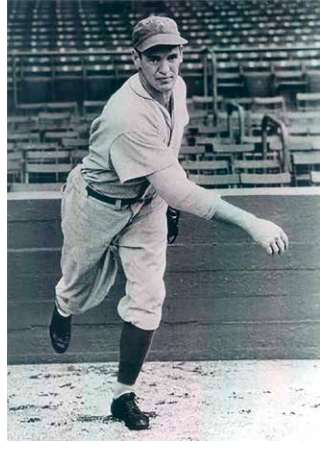

Buster Brown

Family, friends, and teammates could easily have called Charles E. Brown “Charlie Brown” instead of Buster Brown. Given that he would own the worst career winning percentage (.331) for a pitcher with a minimum of 150 decisions, a name that long after his death would have recalled the perpetually defeated Peanuts comic-strip character would have suited Brown.

Family, friends, and teammates could easily have called Charles E. Brown “Charlie Brown” instead of Buster Brown. Given that he would own the worst career winning percentage (.331) for a pitcher with a minimum of 150 decisions, a name that long after his death would have recalled the perpetually defeated Peanuts comic-strip character would have suited Brown.

In Leviathan, the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes opined, “Life is nasty, brutish, and short.” Sadly, these six words well encapsulate the professional career and truncated life of Buster Brown, a slightly-below-average hurler who had the dual misfortune of toiling for truly terrible teams before his untimely death at the all-too-abbreviated age of 32.

Born in Boone, Iowa, on August 31, 1881, Brown stayed closed to home by attending Ames Agricultural College, now known as Iowa State University, where he went 14-0 as a sophomore.1 He pitched no-hitters against Coe College, striking out 16, and against Grinnell College with 14 strikeouts.2 Described by his alma mater “as an exceptional pitcher and captain of the 1905 team,”3 Brown mixed baseball business with collegiate pleasure by playing university ball during the school years and pro ball during the summers. He pitched for semipro Onawa (Iowa) in 1902, in the Three-I League for the 1903 Rock Rapids (Iowa) Islanders, and in the Western League for the 1904 Omaha Rangers.4

The St. Louis Cardinals bought Brown from Omaha in the summer of 1904 and had high hopes for the young righty. Going into the 1905 season, a member of the St. Louis front office claimed that Brown would “make some … batters think [Christy] Mathewson is doing the pitching before the season is half gone.”5

Brown, “the former handler of the expectoration pellet,” had other ideas and received permission to delay reporting until June 1 so he could finish the college term.6

The Cardinals occupied sixth place in the National League standings when Brown made his major-league debut, on June 22, 1905. The circumstances seemed favorable: St. Louis hosted Boston, which languished in seventh place and would send Vic Willis and his 1-11 record to the mound. Brown hit hard and got hit hard. He tripled in his first at-bat but gave up eight runs on 11 hits in six innings of toil. Brown “sustained all of the blows familiar to the big gunners, got rattled just like a veteran, fired [pitches] squarely over the plate, indicating the experience of a trained boxman when about to go for a jaunt in his airship.”7 It was a damning description in the early days of manned flight.

Brown recovered after this subpar start to enjoy a promising rookie campaign.8 Although he had an 8-11 record, his .421 winning percentage bettered the team’s .377 mark. Of the five St. Louis pitchers who pitched in more than 20 games, Brown had the lowest ERA at 2.97. He also tied for the team lead with three shutouts, and finished, despite his delayed start, fourth on the squad in WAR.

Brown had a similar second season, winning eight games again (although losing 16 this time). He set career highs in complete games (21) and strikeouts (109). Facing the Cubs in Chicago in a year when the West Siders would go 116-36, Brown gave up only three hits in a 15-inning complete-game 4-2 victory. Brown survived eight walks and a wild pitch in the win. He held the Cubs hitless after the fifth inning.9

Over the course of 1906, Brown yielded just two home runs and even hit one himself, an inside-the-park job on a “long hit between centre and right fields”10 in an 11-2 loss to the Giants. Brown walked five and threw two wild pitches, a typical outing in a campaign that saw him issue the fourth-most walks in the NL and throw the most wild pitches. Brown struggled with his control throughout his career.

The results of this game notwithstanding, in the 1906 offseason New York Giants manager John McGraw was “hot after” Brown; according to rumor, he was willing to give Joe McGinnity to St. Louis for Brown and [catcher Mike] Grady.11 The deal looked lopsided given that McGinnity had just gone 27-12, the eighth time in eight seasons that he had won at least 21 games, but the Iron Man at the age of 35 had little left. St. Louis supposedly rebuffed the exchange, wanting both cash and players for Brown.12

St. Louis had overplayed its cards. Brown got off to a terrible start in 1907, with a 1-6 record and a relatively high 3.39 ERA (nearly a full run above the league average of 2.46). On June 10, St. Louis traded Brown to the Philadelphia Phillies for left-handed pitcher Johnny Lush.13 In its first issue after the trade, The Sporting News featured Brown on its front page and captioned a photo of him by noting that his “lack of control is a great handicap to have, but if he succeeds in overcoming this weakness, he will rank higher. … He has been charged with sulking during his career as a Cardinal and has several times expressed his desire to enter the services of another team.”14

Although badmouthed on the way out of St. Louis by unnamed sources who accused him of being “too nervous to stand a hard game … and a weakling,”15 Brown found freedom in Philadelphia, where his 9-6 record and 2.42 ERA would have served as personal bests if they could have stood apart from his subpar St. Louis statistics. Capping off a happy campaign, Brown announced after the 1907 season that he would marry Nina Myers of Onawa, Iowa.16

Brown pitched in only three games in relief in 1908 but did get married; a postseason brief notes that he and his wife would return from Philadelphia to Prairie City, Iowa.17 Brown saw little more action in 1909 than he had the previous year; through mid-June, he had appeared just seven times, with only one start. Used in mop-up situations, Brown for the Phillies in 1908 and 1909 had no decisions. Granting its unwanted man freedom, Philadelphia on July 16, 1909, swapped Brown, Lew Richie, and Dave Shean to the Boston Doves for Johnny Bates and Charlie Starr. Boston manager Harry Smith welcomed his new pitcher, saying he expected Brown to be a winner for the Doves. “Brown has loads of stuff, but lacks control, owing to idleness,” Smith noted.18

While defying Smith’s prediction with a 4-8 record, Brown proved a valuable member of the Boston staff, a sad-sack assortment of 15 pitchers, none of whom had a winning record. Brown yielded just 7.9 hits per nine innings, the best mark on the team among the regular starting pitchers. Despite joining the team midway through the season, Brown finished third on the awful 45-108 club in WAR.

In 1910, Boston remained in last place despite winning eight more games than the prior year. Brown easily led the team in WAR and had a fine 2.67 ERA in a year when the NL as a whole had a 3.02 mark. Brown set a career high in games pitched with 46, ranking him in a four-way tie for third in the league, and in innings with 263. But in this, his best season, Brown went just 9-23 (just trailing his teammate Cliff Curtis in this dubious category; Curtis had a 6-24 record).

One of Brown’s nine wins came on May 26 when he stifled the defending World Series champion Pittsburgh Pirates on a complete-game, four-hit effort in a 4-1 Boston road victory. The Boston Globe reported that Brown’s “delivery proved puzzling to the champs.”19 Perhaps his most painful defeat came against a man to whom he had once been crazily compared, Christy Mathewson.20 Facing Big Six and the Giants, a first-division club, Brown through eight innings had yielded just one hit and enjoyed a 3-0 lead. But New York rallied for a trio in the ninth to tie the score; an error in the 14th sparked a five-run rally that led to a frustrating 8-3 loss for Brown. The Globe concluded, “While Brown was effective with his slow ball, he failed to put on the extra speed and at the close was outpitched by the wonderful Mathewson. … Brown pitched one of the prettiest games seen at the park in a long time, and but for a slip in the last ditch would have a good one on the [one and] only Matty.”21

In 1911, Boston bottomed out with a 44-107 record, helped in part by a 14-game losing streak suffered by Brown after he had pitched brilliantly on Opening Day to beat Brooklyn. After this strong start, a Boston correspondent optimistically opined, “Brown has the makings of a first-class box artist. With a strong club behind him I think he would prove to be one of the best twirlers in the league.”22

Alas, Boston had a terribly weak club with “a very error-prone defense.”23 Fred Tenney managed the Rustlers; his career winning percentage as a skipper, .334, only slightly eclipsed that of Brown, his most-used pitcher. Brown lost to Philadelphia on April 19 and kept on losing through July 28 against Pittsburgh, a streak he finally broke by beating St. Louis on August 2, Boston’s first win after dropping 16 straight games. Over the last two-plus months of the season, Brown got even wilder but proved tougher to hit; his 7-4 record over the closing stretch appears even more impressive in comparison with Boston’s 37-103 mark over the rest of the season.

1911: A Tale of Three Seasons24

| W-L | IP | H | BB | K | WP | HBP | R | ERA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| April 12 | 1-0 | 9 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.00 |

| Apr 19-Jul 29 | 0-14 | 137 2/3 | 167 | 60 | 48 | 4 | 6 | 111 | 7.26 |

| Aug 2-Oct 9 | 7-4 | 94 2/3 | 84 | 54 | 27 | 2 | 4 | 48 | 4.56 |

Completing a four-year stretch in which he went just 25-64, Brown bottomed out in terms of winning percentage in 1912 by taking just four of 19 decisions although for the only season in his career he struck out more batters than he walked (68-66) and had a career-best WHIP of 1.259. He pitched a one-hitter against Philadelphia on May 2725 before suffering through another months-long winless streak beginning with his next appearance. Brown went 0-11 from May 31 through September 10. He earned his final win on September 14, 1912, in game two of a doubleheader against St. Louis. In a complete game, Brown gave up only eight hits while leading both teams with three hits of his own, including two doubles, as Boston won 11-2.

Even after four frustrating seasons, Brown had high hopes for 1913. After signing his contract, Brown penned a letter, writing, “I hope this will be our banner year … and I have a feeling that … the team will be much stronger than it was last year.”26 Boston did go from 52 wins in 1912 under Johnny Kling to 69 wins in 1913 under George Stallings, but Brown did not contribute. He pitched just twice, both times in long relief in April home games that the Braves easily lost.

Unwittingly, Brown helped the 1914 Miracle Braves triumph. On May 1, 1913, Boston traded Brown and $4,000 to Toronto of the International League.27 The Braves received Dick Rudolph, who in 1914 alone won three more games for Boston than Brown won in his 139 games pitched in the Hub (Rudolph’s 28 wins included 26 in the regular season, and Games One and Four of the World Series sweep of Philadelphia).

Brown would not live to see the miracle. He died on February 9, 1914, at the age of 32 “after an operation for a growth under his arm.”28 His death certificate lists the cause of his death as acute lymphangitis with a contributing factor of dilation of the left ventricle of his heart.29

This biography is included in “20-Game Losers” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Emmet R. Nowlin.

Notes

1 “Buster Brown, ‘Losing Ways” diamondsinthedusk.com/uploads/articles/153-img2-BROWN_Buster.pdf (accessed March 1, 2017). 2 “Charles E. Brown, Pitcher of the St. Louis National Club,” Sporting Life, May 11, 1907: 1.

3 “Diamond Reflections: Cyclones in the Majors,” add.lib.iastate.edu/spcl/exhibits/baseball/majors.htm

(accessed March 1, 2017). 4 Diamonds in the Dusk credits Brown with a 27-15 record, 107 strikeouts, and 63 walks in 1904. Baseball Reference lists Brown with 28 games pitched (and 63 walks) that season.

5 Wm. G. Murphy, “St. Louis Sayings,” Sporting Life, February 25, 1905: 8.

6 Wm. G. Murphy, “St. Louis Siftings,” Sporting Life, March 11, 1905: 2.

7 “Brown Bounced,” Boston Globe, June 23, 1905: 8.

8 “Brown of St. Louis, with his strength and two months’ experience, has developed into one of the stars.” “National League News,” Sporting Life, September 16, 1905: 3.

9 “Spuds Drop Two but Retain Lead,” Chicago Tribune, May 31, 1906: 11.

10 “Easy Win for Giants,” New York Times, June 17, 1906.

11 Wm. F.H. Koelsch, “Metropolitan Mention,” Sporting Life, December 22, 1906: 10.

12 “National League News,” Sporting Life, December 29, 1906: 7; “New Year Notes,” Sporting Life, January 5, 1907: 10; “National League News,” Sporting Life, February 23, 1907: 5.

13 St. Louis also received $5,000, according to “Local Jottings,” Sporting Life, June 22, 1907: 7.

14 “Charles E. Brown,” The Sporting News, June 15, 1907: 1.

15 “An Odd Handicap,” Sporting Life, July 6, 1907: 5.

16 “Buster Brown to Marry,” The Sporting News, December 12, 1907.

17 “The Phillies’ Winter Quarters,” Sporting Life, October 31, 1908: 5.

18 “National League Notes,” Sporting Life, July 31, 1909: 9.

19 “Boston Wallops Groggy Pirates,” Boston Globe, May 27, 1910: 7.

20 The two did have similar builds. Brown stood an even 6 feet tall and is listed as weighing 180; Mathewson had an extra inch and 15 more pounds.

21 “New York Wins, 8 to 3, in 14th,” Boston Globe, July 7, 1910: 6.

22 A.H.C. Mitchell, “Boston Briefs,” Sporting Life, April 22, 1911: 5.

23 Tom Ruane, “The Deadball Era’s Worst Pitching Staff,” retrosheet.org/Research/RuaneT/bsn1911_art.htm (accessed March 21, 2017).

24 Data compiled from “The 1911 BOS N Regular Season Pitching Log for Buster Brown,” retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1911/Kbrowb1020091911.htm (accessed March 21, 2017). Small discrepancies exist between the sums of some of these daily results as compared to Brown’s seasonal records.

25 “The Phillies were unable to connect with the curves of ‘Buster’ Brown … and that tells the reason for their whitewash.” Brown went seven scoreless innings, striking out eight and giving up just one hit, according to the box score and game story at “See Both Teams Win in Philadelphia,” Boston Globe, May 28, 1912: 7. Retrosheet has Philadelphia getting two hits off Brown. See retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1912/B05272PHI1912.htm.

26 “Brown Sixth Brave to Sign,” Boston Globe, December 24, 1912: 7.

27 Diamonds in the Dusk credits Brown with a 13-13 record, 228⅓ innings pitched, 80 strikeouts, and 94 walks for Toronto in 1913. Baseball Reference has no data on Brown’s Toronto time.

28 “W.M. Tackaberry’s Toronto Topics,” Sporting Life, April 4, 1914: 13.

29 The death certificate comes from the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s file on Brown. Thanks to Reference Librarian Cassidy Lent of the Hall for scanning the Brown file.

Full Name

Charles Edward Brown

Born

August 31, 1881 at Boone, IA (USA)

Died

February 9, 1914 at Sioux City, IA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.