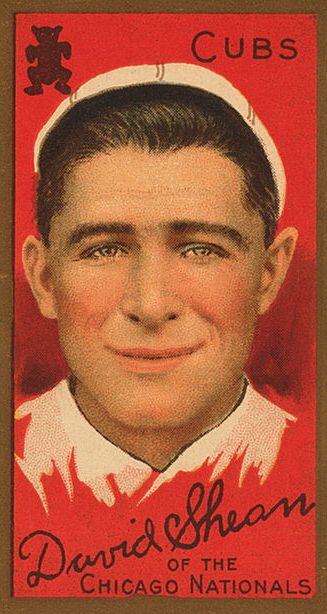

Dave Shean

Dave Shean was the epitome of the Deadball baseball player on the field—he sacrificed runners to the next base, played a steady second base, and collected his share of singles. Off the field, Shean was the opposite of a hard-charging deadballer – he didn’t smoke, drink, chew tobacco, or swear, and regularly attended Sunday Mass.

Dave Shean was the epitome of the Deadball baseball player on the field—he sacrificed runners to the next base, played a steady second base, and collected his share of singles. Off the field, Shean was the opposite of a hard-charging deadballer – he didn’t smoke, drink, chew tobacco, or swear, and regularly attended Sunday Mass.

Shean was born to Irish immigrants, Patrick Shean (a police officer) and Mary, on July 9, 1883, in Arlington, Massachusetts, a suburb five miles northwest of Boston. He grew up with three sisters in a deeply Catholic household at 58 Medford Street, next to Mt. Pleasant Cemetery, and across the street from St. Malachy’s (later St. Agnes) Church, which played a central role in the Sheans’ religious lives.

While attending Arlington High School, Shean’s athletic abilities became evident. The school’s Clarion reported in June 1899 that the left fielder was “playing in good style, capturing nearly everything which comes [his] way.” Shean became a star of the team both at the plate and on the mound before transferring to Boston College High School. After graduating from BC High, he attended Fordham University where he played the infield and outfield and occasionally pitched against other college, semipro, and major-league teams.

During time off from school, he played for a team in Rutland, Vermont, in the Twin Mountain League, where he was spotted in 1906 by Philadelphia Athletics scout Jim Byrnes. Rather than finish his schooling, Shean jumped at the chance of signing with the Athletics, who were coming off an American League pennant. Second base was already occupied by Danny Murphy, who batted just over .300 the year Shean signed. But it wasn’t only Murphy who stood in Shean’s way. A week after Shean’s debut with the Philadelphia American League team, another second-sacker and college boy, Eddie Collins, started his 25-year career. Collins went on to become one of the best second basemen in baseball history and was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1939.

With the Athletics finishing a disappointing fourth in 1906, Connie Mack gave Shean some playing time at the end of the season. He played in his first major league game on September 10, 1906, collecting a hit and a sacrifice in a 2-1 win over Washington.

Within two weeks of his first game, Shean initiated of the rarest feats in baseball – a triple play. In a game against the St. Louis Browns, Bobby Wallace stepped to the plate with runners on first and second. The two runners took off with the pitch and Wallace hit a line drive to Shean, who snared the ball and threw to shortstop Simon Nicholls, who touched second to double off Pete O’Brien and relayed the ball to first baseman Harry Davis, who retired Ike Rockenfield before he could get back to the bag at first.

After a trial in which Shean played in 22 games, collecting 75 at-bats and batting .231, the A’s sent him to Montreal in the Eastern League in 1907. The following year, Shean played for Williamsport in the Tri-State League, where he led the league with 97 runs scored and hit .282 for the league winners.

With Murphy still the starting second baseman for the A’s and young Eddie Collins waiting in the wings, Mack sent Shean to the crosstown Phillies, where he played shortstop for 14 games (with a .146 average) in 1908.

Shean’s stay with the Phillies did not last long. After he had played 36 games in 1909, the National League team sent Shean to the Boston Doves, later renamed the Braves.

Back in his hometown, Shean got the chance to play regularly for the second-division team. He led the National League in putouts, assists, double plays, and chances per game for the position in 1910, while batting .247. One of his highlights that year came when the Doves played Brooklyn. Shean was on second after a walk and a sacrifice bunt. He took off for third with the pitch to Bill Sweeney. Sweeney grounded the ball in the hole between Jake Daubert and John Hummel. Hummel gobbled up the ball and threw to Daubert at first to get Sweeney for the out. At the same time, Shean rounded third and continued to home, beating Daubert’s throw to the plate. The scamper from second to home was becoming Shean’s “specialty,” according to the next day’s Boston Globe.

Following the Doves’ 100-loss season, Boston management tried to trade Shean to the New York Giants, but the team’s board of directors ultimately killed the deal. A month later, though, Shean escaped baseball purgatory and was sent to the Chicago Cubs, who had won the National League pennant in 1910.

With Heinie Zimmerman and Johnny Evers already splitting time at second base, Shean spent 1911 playing both middle infield positions. The Chicago Tribune called Shean “an infielder of sufficient experience to jump in a regular job with the Cubs should he be needed.”

When Shean hit camp before the 1911 season, manager Frank Chance spoke positively of him, as someone who could play all four infield positions. The Tribune, however, was more impressed with the second baseman’s wardrobe. “Shean really is in the class by himself when it comes to the glad rags. When he struck Cub headquarters, he looked as if he had been on a strap hanger all the way from the east, for there wasn’t a crease in his garments except those put there by his valet,” according to the Tribune. The crowded infield reduced his playing time, as Shean hit .288 in just 54 games for the Cubs.

The following year, 1912, the Cubs sent Shean to Louisville of the American Association, but he refused to go to Kentucky. The Louisville team suspended him. He was traded to the Bravesin May 1912. After a week, Shean was on the move again, signing with the Providence Grays of the Eastern League.

Shean played the next few seasons with the Grays and resurrected his career by showing his leadership and new-found batting prowess in addition to his hard-nosed base-running and defensive ability. “(In Providence), he had a chance to show some stuff. He was associated with players who had ability and pep,” Fred Hoey wrote in the Boston Herald and Journal.

That first year with Providence also proved a turning point in his life off the field. He married Eleanor Toomey, who the Boston Globe called a “popular East Boston girl,” a handball player and entertainer in shows like the unusually-named East Boston Catholic Literary Association. They settled in his hometown of Arlington.

Back on the ball field, Shean replaced Roy Rock, a Providence favorite, at shortstop for the 1912 season. Out of his natural position, Shean struggled. He moved to second the following year and his play improved.

The year 1914 proved a successful one for both Shean and the Grays. The Grays won the International League pennant (the Eastern League had changed its name) as Shean, the Grays’ captain, batted .334 in 150 games, while knocking out 173 hits, 22 doubles, 14 triples, and seven home runs; he also collected 35 sacrifice hits and 25 stolen bases.

During a one-week period that season, Shean also became acquainted with two people who would impact his life. On August 18, 1914, the Boston Red Sox sent a 19-year-old pitcher named George Herman Ruth to Providence for some seasoning. “Babe” later played with Shean on the 1918 Red Sox and the two remained friends after their playing days.

The other person to make his presence felt that week was David W. Shean Jr., born on August 22, 1914, to David and Eleanor. David Jr. was the Sheans’ only child.

Following the pennant-winning 1914 season, manager Bill Donovan left Providence and took the top job for the New York Highlanders. Rather than search outside the organization, the Grays turned to their popular second sacker to take over the Providence reins.

The Sporting News reported Shean was “the popular choice for the job….Shean will be the manager that the fans are sure to cotton to. He is a clever second baseman – the best in the International League – and will be a worthy successor to Bill Donovan.”

The Providence fans also rejoiced with the naming of the new manager. At a preseason dinner for Shean, “Fighting Dave,” as the Providence Journal called him, was celebrated.

“No leader of a Providence club ever received heartier assurance of support and cooperation than those extended to popular Bill Donovan’s successor on the occasion of his official introduction as guardian of the destinies of the champions,” the paper reported.

Shean was confident of a first-division finish, though he warned fans that the pitching was not as strong as in its championship year.

Shean picked up his first win as a manager over the Buffalo Bisons in the second game of the 1915 season. The Grays fought with the Bisons throughout the year and headed into September with a slight lead.

The Grays’ season soured, though, when the team lost doubleheaders to Buffalo and Toronto, then dropped two more games to Toronto. Buffalo edged the Grays by two games for the title. Though the Grays came up short, fans didn’t cancel an already scheduled victory party after the season. Shean received a sterling silver tea set. The Providence Journal wrote that the Grays’ fans believed “no manager ever fought harder to give the city a pennant” than had Shean.

Shean managed one more year in Providence, but before the 1917 season, with the Grays under new ownership, he lost his job in Rhode Island. Hoey wrote that Shean “was a good manager, whose maxim was ‘Never drive the men. They are human. The easiest way is the best.’ This put Dave ‘in right’ with the players and the result was teamwork in its truest sense.”

In 1917, Shean was back in the majors, playing for Christy Mathewson’s Cincinnati Reds. Shean played in 131 games for the .500 team that included Hal Chase, one of the finest first baseman and crookedest players in baseball history. Though the Reds suffered through mediocrity that year, there were memorable moments. One game of note was when Fred Toney and James “Hippo” Vaughn hooked up for nine innings of double no-hit ball. Shean played second base that day as Cincinnati knocked out its first hit in the 10th inning and won 1-0.

Shean witnessed not only near perfection while playing second base that year. He also played a part in some lunacy. One play in particular was one of the strangest scoring plays possible. The Braves’ Wally Rehg didn’t run out a ground ball hit to Chase at first base. Rather than step on the bag for the out, Chase instead flipped the ball to Shean at second, who tossed the ball to Larry Kopf at shortshop. Kopf rifled the ball to right fielder Tommy Griffith, who completed the putout to pitcher Peter Schneider, who was covering first. The scoring line was 3-4-6-9-1.

Shean continued playing steady ball, leading the league’s second basemen in putouts, assists, double plays, and chances per game. “Any player who can survive a year with Cincinnati without impairing his baseball health is indeed a wonder,” Hoey wrote.

That was the last year Shean would have to play with major league mediocrity. During spring training in 1918, the Boston Red Sox traded pitcher George “Rube” Foster – who had refused to attend spring training because of a pay cut – to the Reds for the gritty second baseman from Arlington.Shean was back home, but a starting job was not guaranteed. Second-base legend Johnny Evers, who played with Shean on the Cubs, was once again his competition.

The Sox made the move for Shean because they were concerned with Evers’ age coupled with the fact that a number of Boston’s players were eligible for the draft and the nation was at war. Shean, on the other hand, was not subject to the draft because he was 34 years old and married with a son.

After reuniting with his old Providence teammate Ruth, Shean got the start at second base for the 1918 Red Sox on Opening Day, and the Sox beat the Athletics, 7-1, with Ruth getting the win.

The early season was not all good times, though. In the second game of the season, Shean was on the wrong side of pitcher Carl Mays’ surly nature. On that day, Mays was hurling a no-hitter going into the eighth inning. Joe Dugan led off for the Athletics with a hard groundball into the hole. Shean tried to trap the ball with both hands, but slipped on the outfield grass. Dugan crossed first base safely and was awarded a single. Still fuming about the play after the game, Mays told the newspapermen that Shean should have been given an error.

Following that brief bump in the road, Shean’s 1918 campaign was one of his finest. “His skill in blocking off the stick, his value as a sacrifice hitter, and his effective batting in the pinches was one of the biggest factors in the Red Sox’ drive to victory,” reported the Boston Post. “And every ballplayer in both the big leagues will freely admit that Dave is one of the wisest infielders in the game and that neither Ty Cobb nor anyone else can put anything across while Shean is on the watch.”

He batted .264 and played in 115 games in the 126-game season, shortened because of the war. Shean missed time that year because of neuralgia, foot problems, a stomach virus, and an infected foot.

The injury bug bit Shean again while the Red Sox practiced for the 1918 World Series. He dove for a line drive and the ball struck his throwing hand, ripping the nail and skin off the tip of his middle finger. Trainer Martin Lawler wrapped the finger in a splint and Shean was ready to play in his first World Series.

In the first game, Shean scored the only run of the contest. Stuffy McInnis singled him home from second base. The Sporting News wrote of Shean’s journey home that he “runs like a turtle on an iceberg.”

After the Sox won two of three games in Chicago, the teams rode the rails back to Boston. While on the trip, players discussed their possible winnings. Dissatisfied with the new rule that the World Series pot would be split between more teams (the two league champions would take 55½ percent of the money and split it 60/40), coupled with cheaper ticket prices that hurt the size of player bonuses, the players discussed taking action.

Shean, Harry Hooper, and the Cubs’ Les Mann tried to meet with the National Commission, which ran baseball at the time, but were rebuffed. The dispute resurfaced later in the Series and the players threatened to strike.

Back on the field, Shean made one of the best plays of the Series in Game Four. In the sixth inning, Ruth walked Lefty Tyler. Max Flack grounded back to the pitcher, who threw wildly to second past shortshop Everett Scott. But Shean, backing up the play, caught the ball while on his knees and dove toward the base, crawling on his stomach to tag the base before Tyler’s foot made contact. Ruth retired the next two batters and continued his scoreless innings streak that stood as a World Series record until 1962.

The Red Sox wrapped up their fifth world championship in Game Six. Shean scored the winning run and collected the last out in a 2-1 win. Though Shean hit only .211 in the series, he scored the first and final runs. Those were the only runs he scored in the six games, but then again, the Red Sox scored only nine runs in all.

World Series champion teams usually have a joy-filled off-season, but not the 1918 Red Sox. Baseball’s hierarchy was upset with the players’ “greedy” demand for more money during the Series. While previous winners received $3,000 to $4,000 for winning the Series, which was more than the annual salaries of most of the players, the Red Sox players collected only slightly more than $1,100.

National Commission member John Heydler told the players they would not receive their World Champion emblems “owing to the disgraceful conduct of the players in the strike during the series.” In response, Sox owner Harry Frazee bought several of the players pocket watches engraved with their names and “Red Sox 1918 champions,” but the National Commission snub haunted the players long after their playing days.

Shean’s grandson, Henry, said his grandfather didn’t talk much about his baseball career, which he said could have been because of the 1918 slight. “Growing up, we always talked about the Red Sox. But he didn’t talk about his career. I think he may have been unhappy about the way things went down,” said Henry Shean.

For the following decades after the snub, Hooper sent letters to the baseball commissioners asking for the team’s emblems. In one printed letter, the Hall of Famer even mentioned Shean, noting that 1918 was his only World Series appearance. Seventy-five years after the snub and nearly 10 years after Hooper’s death, the relatives of the 1918 Red Sox finally received their honors. During a ceremony at Fenway Park, the Red Sox gave the families commemorative pins in honor of the 1918 season.

After the World Series year of 1918, Shean played in only 29 games, and was batting just .140 when the Red Sox released him in August 1919.

Many baseball players struggle with lives after baseball, but not Shean. He returned to his position at Nathan Robbins Company, a poultry firm that employed him during the offseason.

In a December 1918 story in the Boston Post, Hoey wrote, “When the baseball season is over, Dave does not sit around clubrooms or pool halls and tell the natives what’s best in baseball. Instead he exchanges his baseball uniform for a butcher’s frock and (goes) to the big market where he handles more fowls.” Shean spent decades after baseball working for the poultry company in the dank basement of Boston’s Quincy Market.

“You get a tough one now and then just the same as you do in baseball,” Shean said of his poultry work. “Once in a while, I run across one that has spurs like those that Ty Cobb wears. I sidestep those babies. There are all kinds of birds in the poultry game as there are in the big leagues. I get plenty of chances to size up all the varieties.”

Shean worked his way up the company ladder and became president of the business. “His personality is one of the firm’s biggest assets and the Dave Shean smile brings hundreds of new customers every year,” reported the Boston Post.

Shean stayed in touch with the game. According to reports at the time, the Arlington man made trips to Fenway Park when his old friend Babe Ruth came to town with the Yankees. During those visits, Shean presented the Babe with poultry, which the Sultan of Swat devoured.

“He didn’t make it a point to talk about his famous friends,” recalled his granddaughter Leslie Flanagan. “He didn’t make a big deal out of it though he really had quite an exciting life as a younger man. He was very modest about the whole thing.”

Shean remained with the poultry business until the end of his life. His only child, David Jr., who served in World War II and graduated from Harvard University, followed in his father’s footsteps by taking over the leadership role at Nathan Robbins Company. Though Shean did not return to pro ball after his retirement, he played and coached baseball on Arlington’s Spy Pond Field. He also participated in old-timers games in the Boston area.

Shean’s life came to an end in 1963 after the 77-year-old widower suffered numerous injuries in a car accident. He died at Massachusetts General Hospital on May 22. His death was mourned by his hometown. The local newspaper, the Arlington Advocate, called Shean “one of Arlington’s best known and loved citizens.”

Advocate columnist Leonard Collins wrote that Shean was “a very quiet and unassuming man. Dave hardly talked about his playing days, but on such occasions he was wonderful to listen to as he spoke of the men who were known all over the country.” Shean’s funeral was held at St. Agnes Church, where he had spent many hours attending services. He was buried at St. Paul’s Cemetery in his hometown.

Thinking back on her father-in-law’s life, Helen Shean remembered the former ballplayer as the “most generous, thoughtful, quiet man I ever knew.”

After his death, Advocate columnist Collins summed up Shean’s life by writing, “On or off the field, Dave did just great. His quiet charities over the years were many and no one would know about these if the recipients had not divulged his name. Arlington was his home always and he never lost interest in its people or activities.”

Sources

1918: Babe Ruth and the World Champion Boston Red Sox by Allan Wood, 2003

The Year the Red Sox Won the Series by Ty Waterman and Mel Springer, 1999

Hal Chase by Martin Donell Kohout, 2001

Interviews with Dave Shean’s daughter-in-law Helen Shean and his grandchildren Leslie Flanagan and Henry Shean in 2004

The Arlington Advocate

Arlington High School Clarion

Boston Globe

Boston Herald and Journal

Boston Post

Chicago Tribune

Providence Journal

The Sporting News

SABR, triple plays

Full Name

David William Shean

Born

July 9, 1883 at Arlington, MA (USA)

Died

May 22, 1963 at Boston, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.