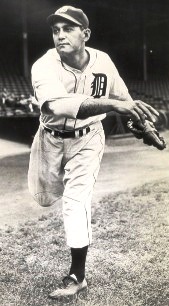

Prince Oana

“Just call me Hank,” said Henry “Prince” Oana. He didn’t really come from Hawaiian royalty, but there was still a certain mystique about this outfielder-turned-pitcher. In a time when mainstream baseball lacked diversity, Oana was something exotic.

“Just call me Hank,” said Henry “Prince” Oana. He didn’t really come from Hawaiian royalty, but there was still a certain mystique about this outfielder-turned-pitcher. In a time when mainstream baseball lacked diversity, Oana was something exotic.

When this story was originally published in 2009, there weren’t many men alive who knew Hank Oana during his baseball days. Kermit Westerholm, a retired sportswriter from Seguin, Texas, was one of them. He hinted at the knockabout life behind the old sepia-toned photos. Said Westerholm (who died in 2014), “There were many quotes which would have made good copy, but I never wanted to violate a confidence. He was one interesting individual. I don’t want to use the word character because he was for real.”1

Yet in the Oana lore, fact and fiction tend to blur. It started before he’d played even a single professional game.

Henry Kawaihoa Oana2 was born in Waipahu, on the island of Oahu. His birthday was January 22, but while baseball references have shown his year of birth as 1908, the bulk of the evidence suggests that it was 1910.3 The man listed as Henry’s father in the 1920 census, also named Henry K. Oana, was of native Hawaiian descent. His mother, Mary, was Portuguese. The couple also had an adopted son named John, who was ten years older than Henry. As of 1920, there were only those four people in the family.

The story is more complicated, though. There is strong evidence that Oana’s biological father was a man named Manuel “Kahuku” Rodrigues. Rodrigues, who later became a Honolulu police officer, acknowledged paternity in a 1930 newspaper story. Rodrigues was also noted for his size and athletic ability.4 The facial resemblance between Rodrigues and Oana is unmistakable.5

It’s possible that young Henry was also adopted. The 1910 census shows a 19-year-old named Manuel Rodrigues living in Kahuku, in Honolulu County, with a wife named Ella and two children named Manuel (born 1909) and Henry (born 1910). A 1963 newspaper report noted that Henry had a brother named Manuel.6

In the past, Waipahu was a plantation town for the Oahu Sugar Company. As of 1910, the elder Henry Oana was a bookkeeper, living and working at Ewa Plantation. He later became station agent for the local railroad depot. In 1924, the plantation manager, Hans L’Orange, established a park with a baseball field where Hank would play. Over 80 years later, a renovated Hans L’Orange Stadium remains in use.

Young Hank was a multi-talented athlete with good size — 6’2” and 190-plus pounds when full-grown. At St. Louis College in Honolulu, now known as St. Louis High School, he lettered in football and basketball as well as baseball. “Nutsky” (the source of this amusing nickname is now unknown) also participated in track and swimming.

Hank was a very good football player. In both 1926 and 1927, he was named to the Interscholastic League of Honolulu (ILH) all-star team as a running back. One Oana legend concerned his booming barefoot kicks, but he dismissed this in 1934. “What do they think we are out there? A lot of wild men of the woods? Sure, I played football and kicked a few goals — with shoes on.”7

Still, baseball was the sport that attracted Oana most. Though he had played in the sandlots as a boy, he did not take the game seriously until he went to St. Louis. The presence of the Hawaii Baseball League, where he played mainly among adults, also helped him develop.

At some point in his late teens Hank Oana married Arma Puninani Richardson. They would have two sons: George (born 1928) and Henry (born 1929). This was the first of at least four marriages for Oana, and it appears to have ended in the early ’30s, after his professional career began.8 Hank had a reputation for loving women and nightlife, and distance from his family was likely a factor.

Like his origins, the story of Oana’s professional signing may have been romanticized. Some accounts say that Ty Cobb noticed the Hawaiian on a barnstorming trip in Japan in 1928, and that he recommended the young man for a tryout with the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League. Cobb was in Japan that autumn on a family trip, also conducting 15 paid baseball clinics.9 Also from fall 1928, photographs exist of Hank pitching for Aratani, a California team sponsored by Japanese-American businessman Setsuo Aratani that traveled to Japan. Both Cobb and Oana faced college teams, so their paths may well have crossed.

It is tempting to dismiss the idea that Cobb would help the dark-skinned Hawaiian, on grounds of racism. The public image of The Georgia Peach as virulent bigot has become ingrained over decades. Part of it was his social milieu; Oana would encounter intolerance some years later when he played in Cobb’s home state, Georgia. Though unproven, there is also suspicion that Cobb may not have accepted the first Hawaiian big-leaguer, Johnnie Williams, as a teammate with the 1914 Tigers. Yet while there is ample evidence of Cobb’s prejudice, he often behaved in ways that defied the caricature.

Hank told the story firsthand of how he joined the Seals organization in a series of Honolulu Star-Bulletin articles in 1932. Nothing of Cobb or Japan was mentioned — the impetus came from George Haneberg, manager of the Braves in the Hawaii League. Haneberg was an old college buddy of Seals part-owner Charlie Graham from the University of California at Santa Clara. After getting the tip from Haneberg, Graham turned tryout arrangements over to club secretary and co-owner George Putnam.10

Ty Cobb and Putnam were good friends; Putnam was “along for the ride” on Cobb’s tour.11 Thus the Seals may have acted on two leads.

Oana left for the mainland after Christmas 1928. He was met by Seals rep Frank Sears, a former first baseman who managed the Granite Bros. club in the local winter league. The weekly games were held on Sundays, and Hank held down a job as a stevedore the rest of the time because the Seals believed hard labor was good conditioning. In spring training he was tried at various positions, mainly the ones where he would spend the bulk of his career, outfield and pitcher. Out of a pack of 150 prospects, Hank survived to make the opening day roster, mainly because of his strong hitting.12

The 21-year-old was very raw in the field, however, and he was not getting any game experience. So the Seals sent him to the Globe Bears, their affiliate in the Class D Arizona State League. Hank posted excellent numbers with the bat, but his fielding average of .903 was worst among the league’s regular outfielders. Thus he required more seasoning. In 1930 his power led the Bears to a first-half championship and won him promotion to the Seals.

Oana followed up his showing in the second half of the season by winning a starting job in the San Francisco outfield. He had spent the winter on the construction crew that built Seals Stadium.13 Playing in 172 of 187 games for the 1931 PCL champs, he led the league in triples and ranked in the top ten in various other categories, although his fielding was still on the shaky side.

Unfortunately, he suffered a drastic reversal in form in 1932. Hank himself attributed the slump to early-season illness and vision problems, which a specialist diagnosed as the result of a growth in his nose caused by a kick received in his football days.14 However, what Oana didn’t discuss with his hometown paper was that he’d allegedly been drinking more than was good for him, sometimes not showing up at the ballpark. The eldest DiMaggio brother, Vince, supplanted him in center much of the year. With three games left in the 1932 season, Hank and shortstop Augie Galan left San Francisco to go barnstorming in Hawaii. This opened the door for 17-year-old Joe DiMaggio to make his professional debut at short.15

After the 1933 season opener, Oana got into a nightclub brawl, with charges pressed by a young woman. The incident cost him a $50 fine and a night in jail. Charlie Graham released him from the Seals, although the club could well have sought an excuse to make room for Joe DiMaggio. A PCL rival, the Portland Beavers, picked up Hank. Manager Spencer Abbott told The Sporting News: “I gave him a bawling out. I told him that a fellow with his ability should never have to go seeking a job, that the job should seek him, and I asked him how much salary he wanted. He said he had been getting $300 a month from Frisco. Think of that, a fellow who could drive in 150 runs a year.”16

Abbott warned Oana that he would rescind his $400-a-month contract if the player ever failed to show up for a game. On his best behavior — and having undergone an operation to help his eyesight — Oana rebounded with an excellent year as the Beavers took the PCL title. He led the league in doubles (63) and extra-base hits.

The Sporting News spread the idea that Spencer Abbott coined the “Prince” nickname, but he just jumped on board. “I sold them on the Hawaiian royalty stuff,” Abbott said later, but a 1929 wire service photo of Oana’s Seals tryout contains the first known reference. The San Francisco newspapers continued to spread the myth after that and Hank played along with the publicity stunt up to a point. It may be, however, that he felt he was endangering his chances of making the majors. Although there had been a number of rather dark-skinned Latin American players, it was still 14 years before Jackie Robinson’s debut, and the less attention to this issue, the better.

Hank declared, “There’s nothing to it. I’m just a kid from a sugar plantation who hopes to make good in the big leagues. I’m interested in baseball, not titles. The more I denied them [stories of his royal bloodlines], the more people believed them. They’re all untrue. I’m just plain Henry Oana; just call me Hank.”17

In November 1933, the Philadelphia Phillies obtained Oana’s contract. In return they sent cash, Frank Ragland, Jimmy McLeod, and a player to be named the next spring to Portland. One of the Phillies’ scouts, Patsy O’Rourke, had had his eye on Hank since 1930. It was a contingent deal, similar to today’s Rule V draft. The Phils paid $2,500 up front and would make it a total of $20,000 if Oana lasted the full season with them in ’34. They hoped that the Hawaiian would replace Chuck Klein, who had been traded to Chicago coming off a Triple Crown year (and rightly so — one of the less deserving Hall of Famers would never be nearly as good again). Oana played just six games in Philly, though, going 5-for-21 (.238).

Hank’s return to Portland lasted only a couple of weeks before Spencer Abbott, now managing the Atlanta Crackers of the Southern Association, reached out for him. In his first at-bat, Oana hit a grand slam, the first of his league-leading 17 homers. In 1946, Abbott commented: “At Atlanta we needed a powerful righthanded hitter who could hit that ball into those Negro bleachers in left field. We needed a hero for our colored citizens. Oana was the man.

“As soon as the Phillies returned Hank to Portland, I wired [Beavers owner] Tom Turner, who was in the market for cash: ‘Name your price for Oana.’ He replied, ‘Five thousand.’ I wired back, ‘Sold, send him right away by airplane.’ Then I wired Hank to come dressed in his best and to wear one of those Hawaiian leis around his neck.

“He whacked that ball a country mile. And he kept whacking it for the rest of the year. He had ability, but that playboy reputation cost him a chance to go back to the majors.”18

Oana was sold to Syracuse of the International League two months into the 1935 season. Perhaps one of the reasons was racial animus; “one newspaper, Hearst’s Georgian-American, swore daily that he was black and it didn’t approve, as if it were any of its business.”19

The Chiefs finished second behind Montreal in the regular season that year, but beat the Royals in the playoffs to take the Governors’ Cup. Hank was highly popular in Syracuse, receiving an English bulldog as a prize for winning the fans’ vote. After the season was over, he brought Buster the dog back home to Hawaii, taking a cruise via the Panama Canal. But upon arrival, he had to place the animal in quarantine for 90 days, and had to leave for spring training before he could free Buster personally.

Oana was also married again when he went back home. On October 31, 1935, he wedded Joyce Powell, a young Alabama-born woman who lived in the Phillies’ spring training site, Winter Haven, Florida.20

Hank moved on to Baltimore a month into the 1936 season. It’s remarkable that even though he spent less than a year total in Syracuse, fans named him as the club’s all-time center fielder nearly a decade later. But his performance declined that year and the next, split between Knoxville and Little Rock, once again in the Southern Association. Plagued by injuries, Oana was released and spent some time with the Hickory (N.C.) Rebels in the “outlaw” Carolina League.

After failing to make the Milwaukee Brewers (paying his own expenses in spring) and the Minneapolis Millers in 1938, the Prince stepped down to the Class B Southeastern League. At Jackson, he led the circuit in homers and RBIs in ’38 and ’39 and was the all-star left fielder both years. Rejuvenated, Oana was able to climb back up the ladder, as Fort Worth of the Class A1 Texas League bought his contract for the 1940 season. Hank was moderately successful in his first two years with the Cats, but his average and power steadily eroded.

In 1942, however, Rogers Hornsby took control of the club — and the second phase of Oana’s career began. Hornsby was a top-rank Hall of Fame hitter, but he was a poor manager who inevitably lost the ear of his players in a matter of months. The Rajah was rigid, brutally tactless, and proud of it. His remark to Hank, “You hit like a pitcher,” was actually rather mild by Hornsby standards. But Oana replied, “I am a good pitcher.” The Sporting News wrote: “‘I oughta be pretty good,’ Hank says with a bashful grin. ‘I was a pitcher as a kid and I’ve been practicing to be a pitcher ever since I’ve been in the States. Every time I’ve warmed up for 10 years I’ve thrown to a guy with a mitt and thought about pitching. I’ve watched and studied men on the mound all these years with the idea that perhaps I’d go for pitching seriously when I slowed down or my hitting slipped.’”21

In fact, Oana had made seven relief appearances the previous year, and one apiece in both of his seasons with Jackson. He had also appeared on the mound occasionally back in 1930-32 for Globe and San Francisco. But he had never recorded a decision before he entered the Fort Worth rotation and became an instant smash. He allowed only 5 earned runs in his first 67 innings, fired three shutouts — including a no-hitter on July 5 — and ran off a streak of 41 scoreless innings, just one short of the Texas League record. He finished the season at 16-5, 1.72.

Rogers Hornsby remarked, “He throws the ball where he wants it and gives the batters nothing good to hit. He knows a lot more about pitching than most of the hitters give him credit with. He works on ’em, keeps ’em off balance and crossed up. He pitches to their weaknesses. His fastball is faster than it looks.’”22

Hank said of himself, “Of course I’ve got a curve ball and a specialty I call a fork ball, but it’s my fast one that has made me a success. It just sails up and out on right handed batters when delivered above the belt. Pitched low it sails down and out — a kind of slider.’”23

Short of players because of World War II, the Texas League suspended operations from 1943 through 1945. At that time, the legendary promoter Bill Veeck owned the Milwaukee Brewers of the American Association. Veeck, who infused his hustling carny spirit into all his operations, paid Fort Worth $500 down, with $4,500 to come if Oana was not called into the armed forces.

The Prince joined in Veeck’s fan-pleasing adjunct entertainment. He played banjo in manager Charlie Grimm’s jug band, “Grimm’s Garglers.” But in order to make ends meet, the cagey owner was engaging in his customary financial shell games. He released Hank on June 16 — just before he was to make the next payment of $2,500 to Fort Worth. He also claimed that Oana’s draft status had been reclassified from 3A to 1A — i.e., a call from the Army was imminent.

William Bramham, head of the minor leagues, declared Oana a free agent because the Texas League was not operating. Thus the Hawaiian wound up back in the major leagues after an absence of nine years when the Detroit Tigers signed him on June 23. He compiled a 3-2 record out of the bullpen and hit .385 in 26 at-bats, including pinch-hitting duties. His only big-league home run came off Atley Donald of the Yankees on July 3, a three-run blow in the 8th inning. He then got the win in relief as the Tigers added four more runs in the bottom of the 9th.

Oana’s draft card shows his classification as 3A. When no evidence of any change emerged, Bramham ordered Veeck to cough up the $4,500 he owed Fort Worth. But on August 11, Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis overturned this decision and sent Hank back to the Brewers. This didn’t sit well with the veteran, who had been enjoying the step up in pay (to $58 a day). Oana was “gone fishing” for a week before he decided to report to Milwaukee.

After the ’43 season, Veeck sold Hank to the Buffalo Bisons, where he was a solid workhorse, going 28-27 over the better part of two seasons. But in late August 1945, the Tigers called again. Fighting for the AL pennant with the Washington Senators, they needed live bodies, as wartime travel restrictions had resulted in a logjam of doubleheaders.

And so on September 12, in his lone major-league turn as a starting pitcher, the Prince enjoyed his finest major-league hour. He was one strike away from a one-hitter over the Philadelphia Athletics when Bobby Estalella doubled in the tying run on a 3-2 pitch. Hank stayed in the game through 10 2/3 innings, and while the Tigers eventually lost in the 16th, they still captured the flag on the last day of the season.

In his classic memoir Veeck — As in Wreck, the impresario recounted how he tried to get the Tigers to hire baseball acrobat Jackie Price as an entertainer for the 1945 World Series. He stated, “Hank Oana, whom I had sold to the Tigers, had got them into the Series with his pinch-hitting and I was naïve enough to think that entitled me to ask for a favor.”24 Clearly Veeck’s memory was fuzzy on this point some 17 years later, but Hank’s contribution to the pennant race was recognized. Although he was not on the postseason roster, the club awarded him a ring after taking the Series over the Cubs.

The Texas League was back in action after the war ended, and Oana joined the Dallas Rebels. The 36-year-old, described by Dallas Morning News sportswriter George White as “one of those fellows who pitch at least 50% with their heads,” became Pitcher of the Year. He led the league with 24 wins against 10 losses, and even batted .303 with seven homers. Four of those homers came as Hank batted 1.000 in his first 11 pinch-hitting appearances. Nearly 50 years later, Rebels owner George Schepps — by then 96 years old — recalled, “He hit them from the right side of the plate with only his left hand on the bat.”25 The Sporting News had noted that “a born disposition to turn loose his left hand when he wields the mace…takes much of the power out of his swing.” But Mr. Schepps’ memory makes more sense — a righty batter would not be likely to let go with his bottom hand, the left.

The Rebels beat Fort Worth (featuring a 20-year-old Duke Snider) in the Texas League finals, and then captured the Dixie Series over Atlanta. Oana notched four more wins in the playoffs. However, that was the last major effort Hank had in him. Reportedly he received an offer to play winter ball with Aguadilla of the Puerto Rican Winter League that offseason, but it appears he turned it down. The late José Crescioni, the foremost recordkeeper of the PRWL, showed no mention of Oana in his database.

In limited duty with Dallas in ’47, the Prince contributed a .375 average and a 2-2, 5.23 record. He then downshifted to the Class B Big State League, serving as player/manager with the Austin Pioneers for the next two and a half seasons until he was fired in July 1950. He operated a boat dock on Lake Travis in the offseason.

For his last season in pro ball, Hank moved northeast to Texarkana, also in the Big State League. He played in 11 games, including seven as a pitcher, but could not finish the season. Trouble with his vision had come back to plague him, this time in the form of cataracts and secondary glaucoma. He was unable to accept an offer from old Tiger teammate Paul Richards to coach with the Chicago White Sox.26

Hank endured five eye operations over the next 10 years, but his outlook remained cheerful, as evidenced in a 1963 interview with Joe Falls of the Detroit Free Press.27 He told the story of giving up a homer to Yankees slugger Charlie Keller in 1943. He portrayed this as his return to the big leagues after nine years, and so he dawdled on the mound, agitating catcher Paul Richards. In reality, though, it was the fourth long ball Oana had surrendered that summer.

In the article, which was picked up by the press in Honolulu and elsewhere, it emerged that Hank (then unmarried) had been living and working since 1958 in a rehabilitation center called the Travis Association for the Blind in downtown Austin. Since he retained some of his sight, The Prince served as an instructor to the totally blind. He taught them crafts, such as making brooms, mops, and rubber mats, along with weaving and paper rolling.

Harold Ratliff, sports editor for the Dallas bureau of the Associated Press, also checked in with Hank that fall and again in 1965. Oana’s vision had improved, although he was wearing “paperweights (glasses with lenses as thick as fruit-jar bottoms).” He hoped to land a coaching job thanks to his friendships with Paul Richards and John McHale, then a Milwaukee Braves executive, who had been Hank’s roommate in Buffalo.28

In succeeding years, Oana maintained his lakeside fishing business, a source of personal enjoyment. He was also a captain with the Travis County Sheriff’s Department. He was married to a woman named Cynthia (surname unavailable from Texas records) on June 15, 1968, and divorced on September 15, 1972. On March 9, 1974, Hank got married once again, to Opal Gunn.

As his age advanced, coronary disease became Hank’s chief health problem. He survived six heart attacks before the seventh claimed his life at age 66 on June 19, 1976. He was buried in Austin’s Oakwood Cemetery.

Spencer Abbott said, “I never met a player who was more willing and put out more for you than Hank Oana. He gave me many a laugh but he worried hell out of me those two seasons I had him. But he was a team man always, and smart. Hank had many friends in every town and it was tough for him to live anything resembling the Spartan life. If he had been a less handsome fellow with the same ability, he might be a ten-year star now in the major leagues.”29 In that case, though, the Henry Oana story might also have been much less entertaining.

Author’s note

This biography was originally published in June 2009 and updated in July 2015. Acknowledgment to the research of SABR member Nelson Okino and also of Robert F. Lemke.

Sources

Henry Oana file at National Baseball Hall of Fame Library

Lemke, Bob. “Hawaii’s Playboy Prince Is a Collector’s Challenge”. Sports Collectors Digest, August 2, 1991.

www.ancestry.com

Texas Department of Health records, via USGenWeb online archives.

Franks, Joel S. Asian Pacific Americans and Baseball: A History. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2008.

Bridgewater, Mike. “Hank Oana”. The Texas Krank magazine, unknown date. Later republished in The Diamond Angle magazine, January 2003.

Notes

1 Telephone interview, Rory Costello with Kermit Westerholm, 2009.

2 Previously record books gave Oana’s middle name as Kauhane, but his eldest son George told Hawaiian baseball researcher Nelson Okino that this was incorrect. Certain stories, embellishing the Hawaiian royalty legend, said it was “Kamehameha.”

3 Supporting 1908 is Henry’s own statement in the article cited in Note 7. Supporting 1910 are the 1920 census, his marriage certificate, World War II draft card, death certificate, and grave marker.

4 “Officer Saves Lives of 25 in Raging Flood”, Honolulu Advertiser, November 20, 1930, 1.

5 Photograph of Manuel Rodrigues, from his headstone at Diamond Head Park Memorial Cemetery, supplied by his granddaughter, Donna Burke. In an e-mail to Rory Costello on July 3, 2015, Burke said, “My father Frank was Henry’s half-brother, with Henry being much, much older. Neither my father nor Henry had the last name of Rodrigues. I suspect they were both illegitimate (or Henry was adopted?),” In 1934, however, Henry referred to himself as the only child in the family (see Note 7).

6 1910 census records. In a 1963 column (unknown date), Honolulu Star-Bulletin sports editor Bill Gee noted the death of Manuel (Kahuku) Rodrigues but referred to Rodrigues as Oana’s brother.

7 Kieran, John. “Sports of the Times; The Prince Chap, or Oana From Hawaii”. New York Times, April 19, 1934: 38.

8 Ibid.

9 Stump, Al. Cobb. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: Algonquin Books, 1996: 400.

10 Oana, Henry, as told to Don Watson. “Breaking Into Baseball,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, October 14, 1932.

11 Rhodes, Don. Ty Cobb: Safe at Home. Guilford, CT: Globe Pequot Press, 2008: 119. See also “Cobb to Sail Oct. 20 for Tour of Japan; Will Embark at Seattle With Putnam, Seals’ Owner”. New York Times, October 10, 1928: 24.

12 Oana, Henry, as told to Don Watson. “Breaking Into Baseball (Second Installment),” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, October 14, 1932.

13 Oana, Henry, as told to Don Watson. “Breaking Into Baseball (Fourth Installment),” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, October 18, 1932.

14 Oana, Henry, as told to Don Watson. “Breaking Into Baseball (Fifth Installment),” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, October 19, 1932.

15 Nelson, Kevin, and Hank Greenwald. The Golden Game: The Story of California Baseball. Berkeley, CA: Heyday Books, 2004: 177.

16 Kritzer, Cy. “Happy Go Roars on Texas Trail”. The Sporting News, July 31, 1946.

17 Undated clipping from 1943, Henry Oana file at National Baseball Hall of Fame Library. Original source: article by Sam Greene in Detroit News, unknown date, 1943.

18 Kritzer, op. cit.

19 Siegel, Morris. “This Hometown Boy Roots for Atlanta”. The Washington Times, October 9, 1991: D1.

20 “Oana, Syracuse Star, Wed to Joyce Powell”. The Poughkeepsie Eagle-News, October 15, 1935: 8.

21 Handler, Zeke. “Oana Hit Like Pitcher, So He Decided to Pitch,” The Sporting News, August 1942 (exact date currently unavailable).

22 Unknown article from The Sporting News, cited in Lemke, Bob. “Hawaii’s Playboy Prince Is a Collector’s Challenge”. Sports Collectors Digest, August 2, 1991.

23 Ibid.

24 Veeck, Bill with Ed Linn. Veeck — As in Wreck. New York, NY: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1962: 107.

25 Sam Blair, “Back to the Minors: North Texas Baseball History Runs Deeper Than Rangers,” Dallas Morning News, July 9, 1995, p. 6Q.

26 Reddy, Bill. “Keeping Posted”. Syracuse Post-Standard, December 4, 1963: 17.

27 McQueen, Red. “Hoomalimali: Prince Oana Heard From”. Honolulu Star-Bulletin, February 3, 1963.

28 Ratliff, Harold V. “Hank Oana’s eyesight returns; hopes to earn coaching job”. Associated Press, March 24, 1965. This article appears to revisit a similar story Ratliff filed in 1963, which is referenced in the story cited in Note 23.

29 Kritzer, op. cit.

Full Name

Henry Kawaihoa Oana

Born

January 22, 1910 at Waipahu, HI (USA)

Died

June 19, 1976 at Austin, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.