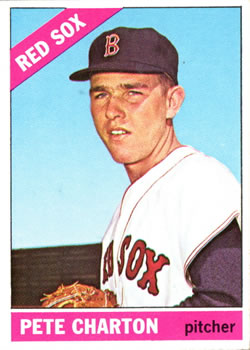

Pete Charton

Pete Charton’s time in the big leagues was brief; he pitched in 25 games for the Boston Red Sox in 1964. It hadn’t taken him long to get there, having worked just one season in the minors beforehand. He showed considerable promise, but professional baseball did not hold the attraction he had hoped for. Before long he pursued other directions in life as a college professor and, ultimately, author of the 2012 book Off to College with King Solomon: A Devotional Handbook for Beginning College Students.

Pete Charton’s time in the big leagues was brief; he pitched in 25 games for the Boston Red Sox in 1964. It hadn’t taken him long to get there, having worked just one season in the minors beforehand. He showed considerable promise, but professional baseball did not hold the attraction he had hoped for. Before long he pursued other directions in life as a college professor and, ultimately, author of the 2012 book Off to College with King Solomon: A Devotional Handbook for Beginning College Students.

Pete was born as Frank Lane Charton on December 21, 1942, in Jackson, Tennessee, the county seat of Madison County, about 70 miles east of Memphis, located on what is now I-40 between Memphis and Nashville. It’s the seventh-largest city in the state and had a population of about 25,000 at the time of Pete’s birth.

Though he was a right-handed pitcher, Charton batted from the left side. He stood 6-feet-2 and was listed at 190 pounds.

His interest in baseball started at a very early age, prompted by his father. “My dad was Frank G. and I’m Frank L. And my mother was Iris Dean Lane. And Lane is my middle name. She was a Texan and Dad was an Okie.

“I was extremely fortunate because both of my parents were just wonderful people. They were gifted intellectually. They came up the hard way. Neither one of them had two cents to rub together when they were growing up. To earn his way through college in Oklahoma, my dad for several years slept under the shelves of a counter in a fried pie shop. He got up every morning about 4 o’clock to fire up the stoves. They both had to earn what they had. Consequently, as is typical of that generation, they didn’t have a lot of patience with bellyaching or making excuses. I had great parents.

“Dad was a wonderful man. He grew up in the Depression, had to work, and never got to play any sports. His uncles were baseball players, and he grew up around it but he just never got to play. When I came along, he was just absolutely determined that if I wanted to play, I would have a chance to play.”1

“My dad was a huge fan,” he told interviewer Andrew H. Martin. “Dad had me throwing I guess at two years old. He would hang my bottles on a string or a rope off the bed because I always liked to throw them against the wall. I would entertain myself by throwing those bottles. Everybody wanted to be a cowboy or a policeman, or whatever, but from the get-go all I wanted to do was play in the major leagues.”2

Pete had a sister. “Pamela. She’s five years younger than I am. She lives in Waco, Texas now. She had a long and good career with Delta Airlines. Her husband was in real estate. When they retired, they moved from Georgia to Texas. Their son went to Baylor. He’s an assistant district attorney now in the county there.”3

Pete’s father “started out as a college prof, of math and music. Then World War II came along. He spent a lot of time in the Pacific. He had battle points from most of the big battles there that the Army was involved with. When he came home, he went into the ministry. He was a minister of music. I’ve often laughed about how many symphonies he could have written if he had not been out there coaching baseball for me. In many Protestant churches — and, technically, Baptists aren’t Protestant but nobody really gets off on that argument any more — in the Baptist church, you typically have a pastor and then a minister of music. The minister of music leads the choirs, he leads the congregation. Of course, he does a lot of other things — administrative things behind the scenes, but what he’s responsible for is the music of the church. The last church my dad was in — this was in Memphis — he had something like 17 choirs and he directed all those himself. From Memphis, we moved to Nashville and he was appointed head of the music department for the Tennessee Baptist Mission Board. He was essentially the coordinator for all the church music throughout the state. He was a very gifted individual. I admired him tremendously. He was a great dad.”4

And Pete’s mother was an achiever, too. First, raising three children, then forging some paths of her own. “My mother went back to school when I was a sophomore in high school, because she didn’t know how they were going to pay for my college. Fortunately, I got an athletic/academic scholarship to Baylor, so my college days didn’t really cost them much. But she didn’t know that at the time, so she went back and started teaching. First grade was probably the first thing she taught. She ended up teaching everything from kindergarten through high school in Nashville. As she was doing that, she continued to go to graduate school and got her degrees. Once she did that, she became a college professor at Belmont University. Her field was English literature and early childhood reading. She set up the first privately run classes for children’s reading in the State of Tennessee. She was very well thought-of across the state. She wasn’t teaching at the private school all the time, but she set it up and watched over it.

“She was a very gifted individual. It gave me a miserable childhood, having a mother who was an English teacher. I say that tongue-in-cheek. Being able to write and use proper grammar is a tremendous asset, and I owe that ability to my mother because she insisted on it.”5

Though he first made his name as a star pitcher for Baylor University, Charton ranked his best memory in baseball as having come in the eighth grade. “I think my favorite moment was in the Knothole League in what would have been the summer of ’55, before the eighth grade.6

“We moved from Memphis to Nashville in the summertime, and what had happened was that all the teams in the Knothole League had been chosen, and I was a latecomer. They stuck me on a team of other people like me — people who didn’t get chosen and all that.”7 It was, he said, “a team of leftovers and scrubs. To make a long story short, we kind of gelled and ended up playing for the city championship. In that game, with the bases loaded, I hit a double and drove in three runs. We were behind at the time and in the last inning, and I drove in three runs to win the ball game. I think of all the ball games I ever played, that was the most exciting one I was ever in.”8 Nearly 70 years later he said, “You know, I can still see the ball hit the bat. It was a chest high pitch, on the outside of the plate, and I can still see that bat hitting the ball just as clear as day.”9

After starring in high-school ball and being named MVP in 1960 (he was also president of the National Honor Society at his high school), Charton attended Baylor. In his sophomore year, in the spring of 1962, Charton threw a three-hitter, a two-hitter, and then a five-hitter for the Baylor Bears, with an 8-2 record and selection to the All-Southwest Conference team.10 He earned an offer from Boston Red Sox scout George Digby. On July 3, he signed with the Sox for an amount thought to be in excess of $8,000 (the actual amount was never publicly revealed).11 He was to report in the spring of 1963. As it happens, he got in some work late in 1962 pitching in the Florida Instructional League.

The Red Sox assigned him to their affiliate in the Single-A Carolina League, the Winston-Salem Red Sox. The team finished 17 ½ games out of first place in its division, but Charton finished with an earned run average of 3.07 and a record of 8-10 in 170 innings of work. He struck out 176 batters, more than one per inning. He returned to Florida Instructional League ball that winter.

That he made the major-league roster of the Boston Red Sox was due to a rule in place at the time. Larry Claflin of the Boston Record American explained:

It must be a nice feeling for a kid like Tony Conigliaro of Swampscott to go to spring training in February and know that no matter what he shows he will stick with the Red Sox next season.

Under the rules of baseball, such is the case. Two other youngsters — pitchers David Gray and Pete Charton — also will stick with the team. None of them is ready for the major leagues, but they’ll be there anyway.

The rule that creates the situation is the so-called “first year rule” which forces the Red Sox to keep their first year players on the 25-man roster or risk losing them for only $8,000 on waivers which cannot be withdrawn.

Four such players will be protected by the Red Sox in 1962. One of them — Tony Horton — will be sent to the minors but the others must be kept all year or placed on waivers. All three must be kept all season. The Red Sox cannot afford to risk losing them.12

The rule obviously hurt player development and handicapped teams, so was shortly dispensed with. But Charton did indeed spend the entire season with the Boston club. Manager Johnny Pesky could only hope to get something out of the first-year bonus rule players on the roster.

He got more than almost anyone would have expected out of Conigliaro, including 24 home runs and a .290 batting average. And Pesky may have used Charton more than intended — he was used in 25 games and threw 65 innings.

He wasn’t used much at first — two innings of relief on April 19 and 1 ½ innings on May 10. He was tagged for two runs the first time out, and (after retiring the first three batters) three more runs in his second appearance. His once-a-month work improved to three calls in June and five in July, all closing games — though all were in games the Red Sox were already losing.

Some of the Red Sox players took him aside to give him pointers. “The person that I probably appreciated the most was Bill Monbouquette. For some reason he took a liking to me. He grabbed me by the shirt collar one of the first days of the season. He sat me down and wouldn’t let me move until we faced every team and pitched to every hitter, and that kind of thing.

“Monbo didn’t have overpowering stuff. He was a really smart pitcher and had really good control. I guess he would remind you a lot of Maddux or somebody like that. He taught me a lot about certain hitters, and then when I would ask him about hitters I was pitching against, he would tell me how to try and pitch them, what their weaknesses were, and all that.”13

With the Sox clearly out of contention, Pesky gave Charton more work in August, calling on him nine times. Over the course of the month, he brought his ERA down from 10.43 to 7.34. He was employed six times in September. As it happens, the Red Sox lost each of the first 22 games in which Charton appeared.

His first start was on September 7 at Dodger Stadium. It was the 21st of those 22 games and ended in a 4-3 win for the Angels. But when Dick Radatz took over for Charton in the seventh inning, the Sox had a 3-0 lead. This was not one of Radatz’s strongest efforts, and he blew the save. Bob Heffner bore the 4-3 extra-inning loss. After his first start, Charton said he was already looking forward to being in the minor leagues in 1965, to get another year of development under his belt. “I’ll get a chance to pitch regularly there, and I figure I’ll be back up with the Sox before too long.”14

Charton’s second start was against the Angels at Fenway Park five days later. He gave up only four hits and one run in seven innings. The score was tied, 1-1, when he departed. Heffner lost that one, too, also in extra innings.

Finally, in his 23rd appearance for the Red Sox, Charton saw his team win the game in which he had pitched. He started against the visiting Minnesota Twins on September 18 and gave up four runs in 4 2/3 innings. The Red Sox were leading, 6-4, when he was relieved, and went on to win the game, but he was one out short of being the pitcher of record, not having completed the first five.

Charton had two more starts and in them received his first two decisions. In neither game did his team score even one run — a 1-0 loss to the Washington Senators on September 23 and a 5-0 loss on September 30 to Cleveland. Only two runners had even reached second base in the game on the 23rd, but one of the two scored and that was the ballgame.

Charton finished the year with a record of 0-2 (5.26). The Red Sox finished in eighth place, 27 games out of first place. And Johnny Pesky finished out of a job, replaced by Billy Herman when only two games remained on the schedule.

It really had been a lost year in terms of development, but he’d learned as best he could and he’d gotten a good taste of the majors.

Had Pete’s father lived long enough to see him make the big leagues? Yes, he had. “There were two great moments in his life. One was when I signed with the Red Sox because he just absolutely adored Ted Williams – thought he was the greatest hitter that ever lived. The second was when I got to play in the majors. My family came to Baltimore and to Kansas City and to Cleveland. They drove to those places from Nashville just to watch me play. Dad was excited about that.”15

Having served his sentence, so to speak, Charton could be farmed out. He pitched in Triple A for Toronto in 1965, Boston’s affiliate in the International League. He had a very good season, 8-5 (2.37) in 16 starts. He’d started well and was 6-2 but then his shoulder gave out. “I pitched a shutout in Atlanta one Tuesday night. The next time I was scheduled to pitch, I couldn’t throw.”16

His arm troubles had started in 1964. “I couldn’t figure out what was going on. And then it started showing up the next season when I was in Toronto. It just seemed to get progressively worse. Finally, as kind of a last-ditch effort, we decided to have it operated on. They never did find the problem until they operated on it. They couldn’t see it on an x-ray, and of course they didn’t have MRIs and all the technology back then.”17

He’d developed some fans in Boston during the 1964 season, and more than one newspaper report (even as late as 1966) mentioned fans in the stands at Fenway holding up signs or banners reading, “Bring back Pete Charton.”18

Near the end of spring training in 1966, with a recurrence of his shoulder issue, he was optioned to Toronto. Before the end of April, however, he was sent back home to Nashville to undergo medical treatment. This also allowed him to continue course work he had been taking at George Peabody College. Beginning in early June, again he was forced to sit out baseball for the rest of the year. In November, it still not having cleared up, he underwent surgery for the removal of calcium deposis in his shoulder.

In June 1967, he was reactivated and optioned to the Pittsfield Red Sox in the Double-A Eastern League. In 13 games there (eight of them starts), he was 3-1 with a 3.67 ERA. He had a shot at becoming part of the Impossible Dream team, but he just wasn’t able to answer the call. “I was throwing pretty well at Pittsfield. I was throwing pretty hard again, but it was hurting and I just knew that it wasn’t going to last all that long. But as a ballplayer you don’t ever say that. About four or five of the front office from Boston came over to watch me pitch. They wanted me to pitch one more game and then I was going to go to Boston, because they were in the hunt for the championship and they didn’t have adequate pitching, other than Jim Lonborg and Sparky Lyle. Of course, I was excited about it. Russ Nixon was my catcher then, and I was throwing before that last game. He said, ‘Pete, you better start throwing harder. The game’s getting ready to start.’ And I never will forget telling him…I said, ‘Russ, it is wide open. That’s all I’ve got.’ He said, ‘Oh, me.’ And I said, ‘Yeah, oh me. It’s gone.’ I pitched about a half-inning and then came out.”

“Then I drove over to Boston from there. I had a meeting with several of the front office and told them that I was just going to hang it up because the shoulder was hurting so much; I was afraid I was going to have to have surgery again. I just didn’t want to do that.

“I’ve had a lot of trouble with the shoulder ever since. If I don’t exercise religiously and lift weights with it, it does give me some problems. Even today.

“The Red Sox and I parted on very amiable terms. They understood.”19

When the Boston team added Ken Harrelson for the stretch drive that year, they needed to clear a roster spot and so released Charton outright to Pittsfield.

“I have wondered for years why somebody didn’t sign me as a hitter,” he said in 2017. “I always thought I was a better hitter than a pitcher. My senior year in high school, I hit .621. The next year as a freshman at Baylor, I hit .520-something. I don’t remember exactly. As a sophomore, I hit .475 or .480, somewhere around there. Nobody even talked to me about hitting. Of course, all I ever wanted to do was play pro ball, thus, I was glad to do whatever they wanted, even if it meant pitching.”20

Were he able to do anything differently about his baseball career, Charton told Andrew Martin, “I would have been a catcher rather than a pitcher. I think I would have made a good catcher. I did some catching when I was growing up; not a whole lot because I had to be either on the mound or the infield. I think that being a catcher is about the fastest way to the major leagues. You can play there the longest if you’re a good defensive catcher and hit .250.

“Pitching was alright in the minors, but you didn’t get to hit and you played once out of every four or five days. I was just always wanting to play every day and would have taken a position where I could have been an everyday ball player.21 I did pinch hit regularly in the minor leagues, and after the shoulder surgery and retirement from baseball I was offered a Red Sox contract in the minors as a hitter/ position player, but I opted to stay in graduate school instead.”

In many respects, Charton was lucky to be alive, much less having made the major leagues. As a teenager, working construction before going to college, he’d stepped on a rusty nail and been given a tetanus shot that was nearly fatal. He had such a reaction that he nearly died, and doctors later assessed that he had been five minutes from death. “I was lucky that the doctor on duty in the emergency ward at the hospital was a specialist in this field and knew what to do.”22 His heart was left so weak that even then doctors wondered if he would survive. The incident was followed by three additional bouts of allergic reactions which left his heart so weak it “couldn’t record a wave on a cardiograph. I couldn’t live a normal life. I could go to high school only half a day and then I would have to come home and stay in bed until the following day. I was so depressed that I started blaming everyone else for my problems. For seven months I couldn’t do anything.”23

It was then, he said, that he knelt beside his bed and prayed. “I asked God to give me the chance to live normally and, if he did, I would dedicate my life to him in every way.” Two weeks later his regular checkup found his heart functioning normally. “Medically, they don’t have a reason. I still believe it was a miracle.”24

And, indeed, there was more to life than baseball. Even when he was, in a sense, on top of the world, pitching in the big leagues, he also had begun to realize something else: “I found I did not like the life associated with professional baseball. I continued to love playing baseball, but I did not like living it. Boredom became the persistent enemy. Sitting in hotel lobbies and movie theaters waiting to play the day’s game, day after day, became unpleasant; and living out of a suitcase while traveling to one large city after another from March to October played havoc with my general attitude. Am I condemning professional baseball with these statements? No, because for many players, professional baseball represents a coveted career; for me, however, it did not fit well. I simply had made poor assumptions. When a shoulder injury and subsequent surgery ended my brief baseball career, I returned to college with an entirely different perspective regarding the role of academics in my life, so much so, that I decided to become a college professor.”25

“I realized that my shoulder was not going to heal properly and was going to be really inconsistent. It took me about five years, I think, to complete my last two years of college. After I finished that I went on to graduate school and got an assistantship at Michigan State. I stayed there for about five years. I received a Master’s Degree and PhD.”26

“I studied physical geography. That was the department that I was in. But as one of my bosses told me, “I’ve never seen a resume that had this much variety in it.” I actually came out of school as a meteorologist. I had a minor in soil science. And I had almost a minor in botany. I had a whole bunch of geology in there; I actually ended up teaching geology most of my college career.

“At the time I was studying the geography of plants. To do that you really had to have an understanding of meteorology. You’ve got to understand soils, and the geology and the botany of it. It all made sense at the time. It prepared me to teach lots of different subjects over the years. I totaled it up one time, and I think I had taught 26 or 27 different subjects in my career. I told somebody I don’t know how good I was, but I was sure versatile.”27

After working as a teaching assistant while finishing his degrees at Michigan State, Charton taught for a couple of years at the University of Illinois. He fully appreciated the university, but felt something of an additional calling. While at Michigan State, he’d met his future wife, Sylvia, in the small Eastern Tennessee city of LaFollette.

This was the late 1960s, he said, and President Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society” initiative had been launched. “I had a professor at Michigan State who had a joint appointment. He was halftime in geography and halftime in education. Although it didn’t pertain to anything I was particularly interested in, he wanted to know if I would go do a research project in education for him. He told me just to choose some poor Southern Appalachian county and here’s what I want to have done. To have a topic that a professor was supporting is really good when you’re doing a thesis, so I said I’ll do it. I called my dad because he knew all the ministers and ministers of music across the state and I said, ‘Dad, where should I go?’ He said, ‘ Well, I know this man who is a pilot. I’ll bet he would fly you all over the area and give you a bird’s eye view, plus introduce you to everybody you need to know.’ I said, ‘That sounds great, I’ll do it.’

The pilot was from LaFollette and the first afternoon was a Wednesday. “Baptist churches always have services on Wednesday nights — midweek services — as well as Sunday. We were flying around up there and he says, ‘Oh, by the way, we don’t have a pastor right now. We’re between pastors. Would you lead the service tonight?’”

Charton had a lot on his plate. He was busy, and tired, “And I was not a preacher, you know, and I had about an hour and a half to prepare for it. But he was so nice to me, I smiled and said, ‘Sure, I’ll do it.’” And there he was that evening speaking to the congregation when he spotted his future wife Sylvia, there with her mother near the back of the room. “It was an immediate connection. After the service we shook hands and looked at each other, and somehow we just knew right there. I don’t know how. We were engaged a couple of weeks later. We married the next spring, 1969.”28

Sylvia herself graduated with honors from Michigan State. She did some substitute teaching, but concentrated on being a homemaker and raising a family.

And in time, they moved from Champaign, Illinois, back to the mountains of East Tennessee to the town of Harriman — near Oak Ridge, west of Knoxville, where he took a position at a new community college being set up in the region, Roane State Community College. He hadn’t really expected to stay at the community college but figured he’d teach there for a couple of years, and then he would move to Oak Ridge where there was always a need for scientists. He taught at Roane State for 35 years.

“It was like new life had been breathed into me. It was almost like a missionary-type experience. They started holding classes in an old house in 1970 and they moved into the new campus building in’72 and I went there in ‘74. Probably two-thirds of the students’ parents had never been to college, and many of these parents had never graduated from high school. To see these students go off to places like Harvard and Emory and Vanderbilt after Roane State prepared them…It was just so gratifying, I never left.”29

Pete and Sylvia have three children. Katie, the second-born, “always wanted to minister to disadvantaged, hurting people.” She first worked with elementary school children, kids who didn’t have English as their first language — English Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL). She helps them understand what’s going on. She has done that for a large number of different language speakers. She has helped so many kids and sometimes assisted frightened parents. She’s helped kids find out they need glasses or this and that, and in some cases she has learned if they’ve been abused at home. I don’t know how she does it.

“Katie is the reason we moved to South Carolina, because of our children she seemed most likely to stay in one place. {Pete and Sylvia moved to Columbia after he retired from Roane State.)

“In the last couple of years, she has largely stepped out of her ESOL role and is teaching seventh grade social studies. She and her husband have three sons.

“Ross, our oldest, is a Lieutenant Colonel. He lives in Georgia. Now out of active duty, he serves in the Army Reserve. Most of his work is done in Huntsville, Alabama. He has two daughters and a step-son.

“Kristi, our youngest, lives just outside of Sevierville, Tennessee. She teaches high school math there, where she, too, has helped so many students cope with life difficulties. Her college football-coach husband and 2 years-old daughter keep her (and us) on the go.”

Looking back on his baseball career, Charton says, “I loved baseball, but when it was over, I knew it was over and I had to look ahead and not backwards. I have had the most wonderful life with my wife and children. I loved my teaching. I have loved my family. It’s just been a great life. I’ve just been so blessed.”30

Last revised: January 18, 2018

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Norman Macht and fact-checked by David Kritzler.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Charton’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks to Eric Manning.

Notes

1 Author interview with Pete Charton, November 7, 2017.

2 Andrew H. Martin, “Catching Up with Pete Charton,” December 4, 2011, at http://baseballhistorian.blogspot.com/2011/12/catching-up-with-pete-charton.html

3 Author interview with Pete Charton, November 7, 2017.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Andrew H. Martin.

7 Author interview.

8 Andrew H. Martin.

9 Author interview.

10 Associated Press, “Charton Signs Pact With Bosox,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans), July 4, 1962: 13.

11 Associated Press, “Nashville Prep Star Signs With Red Sox,” Charleston News and Courier (Charleston, South Carolina), July 4, 1962: 19. Charton told Andrew Martin, “I hate to admit this, but until the week I signed with the Red Sox, I was a Yankee fan, which is terrible.”

12 Larry Claflin, “1st year Rule Handcuffs Sox,” Boston Record American, December 22, 1983: 20.

13 Andrew H. Martin.

14 Tom Monahan, “Charton to Get More Work,” Boston Traveler, September 8, 1964: 44.

15 Author interview. Pete Charton’s favorite player? He told Andrew Martin, “I think my favorite player, and I had a lot of favorites, was Robin Roberts. He was just a great pitcher. He won 20 games so many years for a team that always came in last. I just thought that was really something.”

16 Larry Claflin, “Charton Fights Woes to Stick With Red Sox,” The Sporting News, April 2, 1966: 12.

17 Author interview.

18 Jack McCarthy, “Charton Fans’ Reward Near,” Boston Herald, March 6, 1966: 71.

19 Author interview.

20 Ibid.

21 Andrew H. Martin.

22 Will McDonough, “Back Injury Nearly Finished Charton,” Boston Globe, March 6, 1966: 58.

23 Ibid.

24 Ibid.

25 Dr. Pete Charton, Off to College with King Solomon: A Devotional Handbook for Beginning College Students (Self-published, 2008, rev. 2012), 42.

26 Andrew H. Martin.

27 Author interview.

28 Ibid.

29 Ibid.

30 The last section is drawn both from Dr. Charton’s book and the November 2017 interview.

Full Name

Frank Lane Charton

Born

December 21, 1942 at Jackson, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.