Lloyd Merriman

Lloyd Merriman’s timing couldn’t have been worse. A college football star, he interrupted his studies to serve in World War II. A bonus baby, he was rushed to the majors after a single year in A ball. A Marine Corps pilot, he was called back into service during the Korean War and missed two full seasons in his prime.

Lloyd Merriman’s timing couldn’t have been worse. A college football star, he interrupted his studies to serve in World War II. A bonus baby, he was rushed to the majors after a single year in A ball. A Marine Corps pilot, he was called back into service during the Korean War and missed two full seasons in his prime.

Merriman excelled at everything he tried — except hitting major-league pitching. Could he have mastered that if he’d had a chance to learn his craft in the minors? He thought so. We’ll never know.

His greatest tool was speed — he was nicknamed Citation after the thoroughbred Triple Crown winner — but he played in a time when stolen bases took a back seat to three-run homers, and he never developed a power stroke.

Neither football nor baseball nor his wartime exploits defined him. Family members said he “was a cowboy at heart.”1

Lloyd Archer Merriman was born on August 2, 1924, in Clovis, California, just outside Fresno in the San Joaquin Valley, where the big event was the annual rodeo. His parents, Carl and Bessie (Prussing), ran a grocery store. Lloyd came to baseball naturally; his father been a semipro pitcher. Working part-time at the store, the boy saved enough money to buy gloves for himself and his dad so they could play catch.

Playing at Clovis Union High, in American Legion ball, and on sandlot teams, the left-handed pitcher and outfielder attracted attention from major-league scouts, but followed his parents’ wishes and went to Stanford University. Fellow pledges in the Zeta Psi fraternity talked him into trying out for the freshman football team, and he won a starting spot at fullback.

That was in 1942, the first year of World War II. At the end of his freshman year, Merriman enlisted in the navy and was transferred to the Marine Corps to be trained as a pilot. He played football in the service and did not complete flight training until July 1945, just before Japan surrendered.

First Lieutenant Merriman was released from active duty in time to enroll at Stanford for the spring semester in 1946. He joined the varsity baseball team, batting .390 as the center fielder.

Stanford had gone undefeated in football in 1940, but dropped the sport during the war because of the manpower shortage. Coach Marchmont Schwartz was rebuilding a team from scratch. He quickly realized he had something special in Merriman, a fullback with a halfback’s speed. A United Press reporter described him as “big (197 pounds), fast and hits like a bulldozer.”2

Chosen as team captain, Merriman powered the 1946 Stanford Indians to a 6-3-1 record, including a 25-6 victory in what was known as the Big Game against the University of California. But a hard hit in the second quarter aggravated a leg injury, and he was carried off the field.

After the season the Chicago Bears made him their fifth-round pick in the NFL draft, the 32nd player selected. The Los Angeles Dons of the rival All-America Football Conference tapped him in the third round. Although draft-eligible because his original class had graduated, he showed no interest in signing.

He batted .404 on the diamond in the spring of 1947 while his name was the talk of the coming football season. The Associated Press and United Press had chosen Merriman for their all-West Coast teams, and sportswriters were predicting that he would be a sure All-American in the fall.

Merriman was focusing on his future. He was almost 23, with two years to go for his college degree. The leg injury was still bothering him, and he feared that another season of football might kill his dream of playing major-league baseball. He was also focused on Dilys Jones, a brunette speech and drama major he had met on a Christmas ski trip. “Looking at Dilys, I wondered where I had been spending my time on campus,” he said.3 Marriage was on his mind.

In July he went to Cincinnati with scout Bobby Mattick to work out for the Reds. They signed him for a $12,500 bonus, making him their first bonus baby under a new rule designed to limit payments to untried amateurs.

The news hit the West Coast football world like an earthquake. “The entire team had been built around Merriman,” Stanford athletic director Al Masters lamented.4 He may not have been exaggerating; the Indians didn’t win a single game in 1947. Coach Schwartz understood the decision by a young man who had given three years of his life to the war: “He no doubt figured that if he was to make anything out of his great talent as a ball player there was no time to waste.”5 For years afterward Stanford remembered him as one of its great running backs, in the same sentence with Ernie Nevers and Bob Mathias, a two-time Olympic decathlon champion.

The Reds signed Merriman to a Class-C contract, but after looking him over in spring training in 1948, they jumped him to Class-A Columbia, South Carolina. He lived up to their fondest expectations, leading the Sally League with 120 runs, 18 triples, and 44 stolen bases while batting .298. After Citation won racing’s Triple Crown that summer, fans hung the nickname on him.

With his first pro season behind him, Lloyd and Dilys were married on October 10, 1948, and returned to Stanford to complete their degrees. He was allowed to take final exams before spring training so they could graduate together with the class of 1949.

Under the bonus rule in force at the time, the Reds had to put Merriman on their major-league roster or risk losing him on waivers if they tried to farm him out again.6 After winning back-to-back pennants in 1939 and 1940, the club had fallen out of contention and posted losing records for the last four years. Merriman was one of the few bright spots in the thin farm system. The pressure was on.

“He’s got a great chance to be a star,” manager Bucky Walters said, “because he has the ability — power, speed and a strong arm — and the finest attitude I’ve seen in a young player in years. At spring training he worked harder than anyone else I ever saw, mostly on little things that many young players overlook.”7

Playing center field and leading off on April 24, 1949, at Pittsburgh, Merriman recalled his first big-league plate appearance: “I was so nervous I couldn’t swing the bat. I just stood there and took two strikes. I thought, ‘It’s strike two. I gotta start swinging.’ Next pitch I took a whack at it, and by God if I don’t hit it!”8 He lined it hard into right-center, galloped around the bases like a four-legged thoroughbred, and pulled up with a triple, then scored on a fly ball. Tying a bow on his debut, he clouted a home run in the eighth. He remembered it as a cheap one that barely made it into the right-field stands, but it turned out to be the winning run in a 3-2 victory.

Merriman hit safely in his first five games, but it took National League pitchers only a couple of weeks to catch up with him. As his batting average sagged below the Mendoza Line in June, he was consigned to late-inning defense. Veteran outfielder Danny Litwhiler, a future college coach, became his mentor, showing him the best places to eat around the league and taking him to the park early for extra batting practice.

With the Reds headed for a seventh-place finish, manager Walters put Merriman back in the lineup for the last two months of the season. His bat perked up a bit, but not enough. His final line: .230/.285/.348 in 287 at-bats.

Merriman knew he was overmatched. “Personally I would rather have had three or four years in the minor leagues to do some experimenting — like in base stealing and hitting differently,” he said later. “In the majors you can’t afford to make mistakes.”9

New manager Luke Sewell amped up the pressure the next spring. “Lloyd must come through for us in center field if we are to have a good outfield,” he said.10 Sewell tried to protect him, playing him almost exclusively against right-handed pitchers in a platoon with Bob Usher. Merriman was batting .305 on June 1 and appeared to have figured it out. That day he hurt his wrist crashing into Crosley Field’s center-field wall and missed two weeks. He may have come back too soon. His hitting fell off sharply to a final .258/.330/.349.

Merriman played regularly in 1951 only because there was no better alternative. The Reds were a team going nowhere with the league’s weakest offense. A decent pitching staff kept them close to .500 until mid-July before they tailed off to finish sixth. Merriman hit .242/.303/.359 in a career-high 114 games. He was just 27, but after three years he was showing no progress.

It was to be his last chance. With the undeclared war in Korea stalemated in its third year, the Marine Corps was summoning reservists from World War II back to active duty. “You had a choice when World War II ended,” Merriman explained. “You could go into the inactive reserves and go home immediately. Or you could go to China and finish out your tour. I myself didn’t want to go to China.”11

Merriman and Yankees second baseman Jerry Coleman received their notices in January 1952 and were activated in May. Ted Williams and Cleveland outfielder Bob Kennedy followed close behind. All were pilots. Williams believed the athletes had been unfairly singled out and said so five years later.12 If Merriman agreed, he never aired his feelings publicly.

Merriman hadn’t touched the controls of an aircraft since the war. Along with Williams and Kennedy, he was retrained to fly jet fighters. “Flying a jet was quite a thrill,” he recalled. “The funny thing is how you hear all this sound going down the runway, but about 300 feet after takeoff, all the sound goes away. You think maybe that jet has quit on you, but what happens is you’ve left the sound behind you.”13

He was shipped to Korea in February 1953 to serve in the same unit with Williams and future astronaut John Glenn. The two ballplayers conducted one baseball clinic for enlisted men on a rocky excuse for a field and went duck hunting together once, but Merriman saw that he was not in Williams’s class as a hunter.

Most of their days were spent in the air, a dangerous place to be. Captain Merriman flew 85 combat missions in F-9 Pantherjets, attacking North Korean positions and providing air support for ground troops. Williams famously escaped the crash of his burning plane. A few weeks later Merriman’s jet was hit by antiaircraft fire that knocked out his hydraulic system, disabling his brakes. The ground crew rigged a wire across the runway, like the arresting cables used to stop planes landing on an aircraft carrier. Merriman had never landed on a carrier. He missed the wire and careened off the end of the runway into rice paddies. He walked away stinking of manure that was used as fertilizer.14

He was awarded the Air Medal with four presidential citations and four gold stars. By the time he returned home in September 1953, Williams, Coleman, and Kennedy were already back on the ball field. Merriman played winter ball in Cuba to work himself into baseball shape.

During the offseason he attended a sports banquet in Palo Alto where Ty Cobb was the featured speaker. The two had a conversation lasting far past midnight, with the ancient legend doing most of the talking. Cobb invited him to visit his home in Atherton, California, leading to two more long talks. And Cobb became his pen pal, sending several letters full of advice in his trademark green ink. In one he wrote, “Work yourself up mentally, sore at the opposition and the pitcher.” Merriman appreciated Cobb’s tips but commented, “They worked for him, but not always for me.”15

In the two years that Merriman was away, the Cincinnati club had acquired a new nickname, Redlegs, in response to the anti-communist fever gripping the country, and a new outfield of younger, more powerful hitters. Jim Greengrass, a product of the Yankees organization, played left with Gus Bell, traded from Pittsburgh, in center and Wally Post, who had been Merriman’s teammate in Columbia in 1948, in right.

As he passed his 30th birthday, Merriman served primarily as a left-handed pinch-hitter in 1954, going 11-for-38 with 10 RBIs in that role. Frustrated by the lack of playing time, he told general manager Gabe Paul he was quitting the game, but Paul talked him out of it. Merriman asked Paul to trade him or send him to the Pacific Coast League, close to home.

“Somehow I came to be typed as an in-and-outer with Cincinnati,” he said. “Trouble was, I didn’t get to play enough. … [G]etting in there for just one game at a time and sitting on the bench thinking for a week about that 0-for-4 you got last time you were in there soon convinces you that you can’t hit.

“Trouble was, when I went up there I knew I couldn’t hit major league pitching and so did they. Good hitters tried to help me, fellows like Paul Waner, Gerald Walker, Augie Galan and a dozen others. I was just at an age when I tried everything they told me. And they all had a different theory. They all meant well and I’m grateful for their trying to help me, but I got so many tips from them it mixed me all up. It took me years to learn how to hit.”16

The Redlegs let him go on waivers to the Chicago White Sox. Sox manager Marty Marion soon received a letter from Ty Cobb urging him to give his new outfielder a chance.17 But Merriman got into only one game in 1955 before the club sold him across town to the Cubs.

“The Cubs desperately needed a center fielder and Merriman needed a steady job,” John C. Hoffman wrote in The Sporting News.18 The new Bruin was confident that “if I play regularly I’ll come around.”19 The Cubs gave him a 14-game trial, playing him almost every day. He delivered some highlights, including a four-RBI game with his last home run to beat his former teammates in Cincinnati, but hit only .200 and went to the bench. After he posted a line of .214/.311/.290 in 72 games, the Cubs sent him to their Triple-A club in Los Angeles, then sold him to the Pacific Coast League Portland Beavers. He batted .242 for Portland and retired after the 1956 season.

In an interview that winter, he said his career had been derailed from the start by the bonus rule: “Sure, the bonus I got seemed like big money, but after all it was an obstacle because I needed minor league experience to develop and I couldn’t get it. I was playing big league ball before I was ready. I’m sure I would have been a much better player with proper preparation.”20

Merriman’s disappointing five-year major-league career was unforgettable for one observer: Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully. When Merriman smacked a line drive just outside the third base line one day, Scully meant to say “hot shot hit foul,” but it didn’t come out exactly that way.

Returning home to Clovis, Merriman opened an insurance agency and began breeding horses on his ranch. He continued to play ball for several years for the Fresno Police in the semipro Central Coast League. Lloyd and Dilys raised son Robin and daughters Daryl Ann and Lynn. After Dilys’s death in 1989, he married Suzanne Maree Tuggle. In later years Merriman became a sponsor for Alcoholics Anonymous. Stanford inducted him into its Athletic Hall of Fame and the Clovis school district named the high school baseball field after him.

Although he was celebrated as an athlete and a decorated Marine, Merriman spent most of his life in the role he loved best. “He loved being a cowboy and doing cowboy things,” said his daughter Lynn Hernandez. He competed in rodeo horsemanship events. “He was amazing with a horse,” daughter Daryl Erdman remembered. “Oh, my goodness, he could take a young horse, no trainer, nobody else touched that horse, and he was Reserve Non-Pro champion twice on babies that he raised.”21

Lloyd Merriman died of emphysema at 79 on January 20, 2004.

Acknowledgments

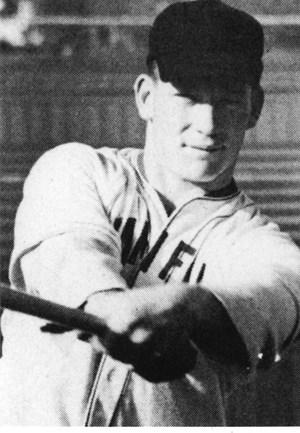

Photo credit: Stanford University Athletics. This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Notes

1 Unidentified obituary in Merriman’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York.

2 Robert Prescott, United Press, “Stanford May Trip Coast Grid Experts,” New York World-Telegram, October 12, 1946, in HOF file.

3 Bob Broeg, “‘Doesn’t Think He Knows Everything,’” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 15, 1949: 2D.

4 Prescott Sullivan, “Merriman Quits Grid to Join Cincy,” San Francisco Examiner, August 10, 1947: 25.

5 Sullivan, “The Lowdown,” Examiner, August 11, 1947: 17.

6 The 1947 bonus rule classified any player receiving more than $6,000 as a bonus baby. The rule was repealed in 1950, then strengthened in 1952 to require any player receiving more than $4,000 to be kept on the major-league roster for two years.

7 Broeg, “‘Doesn’t Think He Knows Everything.’”

8 Jim Sargent, “An Interview with Lloyd Merriman: Football Star, War Hero, Big Leaguer” in Baseball in the Buckeye State (SABR, 2004), 46.

9 United Press, “Merriman Feels Sorrier for Williams, Coleman Than Self,” Fresno Bee Republican, September 3, 1952: 21.

10 Lou Smith, “Blackie Starts Today Facing Washington Club,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 18, 1950: 15.

11 Leigh Montville, Ted Williams: The Biography of an American Hero (New York: Doubleday, 2004), 152.

12 Montville, Ted Williams, 153.

13 Sargent, “An Interview with Lloyd Merriman,” 48.

14 Montville, Ted Williams, 166-167.

15 Bruce Farris, “Script of a Legend,” Fresno Bee, July 18, 1997: D4. Several of Cobb’s letters are in Merriman’s HOF file.

16 “Merriman Victim of Too Many Hitting Tips,” The Sporting News, March 2, 1955: 19.

17 John P. Carmichael, “The Barbershop,” Chicago Daily News, March 1, 1955, in HOF file.

18 John C. Hoffman, “Merriman Brings Some Cheer to Worry-Man Hack of Bruins,” The Sporting News, May 4, 1955: 10.

19 Associated Press, “Merriman Gets Big Break Landing with Chicago,” Oakland Tribune, April 25, 1955: 38.

20 “Merriman Hangs Up Glove, Regrets He Accepted Bonus,” The Sporting News, December 26, 1956: 19.

21 Clovis United School District, “CUSD Hall of Fame 2017 — Lloyd Merriman,” video tribute at https://vimeo.com/241740012, accessed June 12, 2019.

Full Name

Lloyd Archer Merriman

Born

August 2, 1924 at Clovis, CA (USA)

Died

January 20, 2004 at Fresno, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.