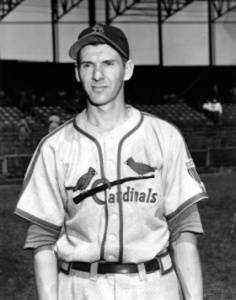

Marty Marion

Before the Wizard of Oz, the St. Louis Cardinals had Mr. Shortstop. Marty Marion never turned a backflip, but he was the National League’s premier defensive shortstop in the 1940s and is the only man to win a Most Valuable Player award with his glove.

Before the Wizard of Oz, the St. Louis Cardinals had Mr. Shortstop. Marty Marion never turned a backflip, but he was the National League’s premier defensive shortstop in the 1940s and is the only man to win a Most Valuable Player award with his glove.

No Scooter or Rabbit or Pee Wee, he was a different breed at 6-foot-2 and 170 pounds. His long legs and arms earned him another nickname, “The Octopus.” The sportswriter Red Smith said he “could go and get balls nobody else could reach.”1 Baltimore manager and St. Louis native Earl Weaver shifted the 6-foot-4 third baseman Cal Ripken Jr. to short because “he reminded me of Marty Marion.”2

Mr. Shortstop’s legacy extends beyond the infield. Every major leaguer who came after him owes him, because he was the father of the players’ pension plan.

Marion joined the Cardinals in 1940 as the last members of the Gashouse Gang were leaving. He was part of a new generation with Stan Musial, Enos Slaughter, and the brother battery of Mort and Walker Cooper who led the team to the most successful run in its history. In the twilight of the Branch Rickey era, the Cards won 606 games in six years, 1941-1946, capturing four pennants and three World Series championships.

Friendly and approachable, Marion was one of the most popular Cardinals. Six decades after he last wore the uniform, the club’s general manager, John Mozeliak, said “I never met the man, but I’ve met scores of Martys in my time in St. Louis and they all told me they were named after Marty Marion.”3

Martin Whiteford Marion was born in Richburg, South Carolina, on December 1, 1916 (he was a year older than his “baseball age”), the second of four ballplaying sons of John and Virginia Marion and the only one who wasn’t a redhead.4 His older brother, Johnny, called “Red” in baseball, played outfield briefly for the Washington Senators and was a longtime minor league player and manager. Younger brothers Roy and Charles also played in the minors. The Marions were said to be descendants of Francis Marion, a Revolutionary War guerrilla fighter known as the Swamp Fox.

While his blond son was still in diapers, John Sr. moved the family to Atlanta for a job with the Georgia Power Company. John, who had hoped to try pro ball until a broken leg sidelined him, played second base for the company team.

When Marty was 10 he fell down a steep embankment, suffering a compound fracture of his right leg. He spent months in traction and couldn’t walk for more than a year. His mother was protective, but his father allowed him to play baseball at Tech High School and on an American Legion team as a power-hitting third baseman.

Red Marion was playing for Chattanooga in the Southern Association when Marty graduated from high school in 1935. The Lookouts gave Red’s kid brother a tryout and a token contract. Marty was left behind when the team went on the road, so he went home to Atlanta to see his girlfriend. The business manager, Calvin Griffith, complained that he should have stayed in Chattanooga to work out, but Marion protested that nobody had told him so. Griffith handed him his release.

Marion enrolled at Georgia Tech with plans to study architecture. After he showed his stuff at a Cardinals tryout camp, he and a third baseman from a rival high school, Johnny Echols, were invited to St. Louis. The pair made a pact that neither would sign without the other. They worked out at Sportsman’s Park for general manager Branch Rickey and manager Frankie Frisch. The Cardinals brass liked Echols, but Frisch thought Marion was hopeless with the bat. Rickey’s brother Frank eventually signed both.

Marion reported in 1936 to the Cardinals’ mass spring camp for their hundreds of farmhands. On the first day he saw 11 players milling around third base, so he trotted out to shortstop, where there was less competition. Burt Shotton, the manager of St. Louis’s Columbus farm club, is usually credited with nicknaming him “Slats” after the “Abbie an’ Slats” comic strip. Slats was the skinny one.

For the next four years Marion worked his way up through the Cardinals system. Along the way he married his girlfriend, Mary Dallas, on December 27, 1937. In 1939 Branch Rickey offered to sell the Chicago Cubs either of the Cardinals’ two shortstop prospects, Marion and Bobby Sturgeon. The Cubs paid $50,000 for Sturgeon, who played in the majors for six years without any resemblance to Marion.

After trading Leo Durocher in 1937, the Cardinals tried out seven shortstops over the next two years. The 23-year-old Marion (who was believed to be 22) won the job in 1940 with his glove and strong arm. He was a below-average hitter for most of his career, batting in the .260s and .270s without power while slotted seventh or eighth in the order.

St. Louis began its run of success in 1941 under manager Billy Southworth. The club won 97 games, but the Brooklyn Dodgers won three more. The next year, with rookie Stan Musial joining the lineup, those two teams staged an epic pennant race. The Dodgers stretched their lead to 10 games in August; then the Cardinals took off. They won 26 of their last 30 to edge Brooklyn by two games, and upset the mighty Yankees in the World Series.

The Cardinals’ 106 victories were the most in the National League since 1909. They were called the “St. Louis Swifties” because they consistently took the extra base, leading the league in doubles and triples. Marion and Musial always said the ’42 club was the best they played on. The season was Marion’s best at the plate. He hit .276/.343/.375 with no home runs but a league-leading 38 doubles, the only time he led the league in any batting category.

Just three of the team’s regular position players and pitchers were past 30. They were a dynasty in the making, even though most of the young Cardinals went away to military service over the next three years. Branch Rickey left St. Louis after 1942, but his farm system supplied replacements for the departed players. Marion was never drafted because of his childhood leg injury and a knee injury suffered in his rookie year.

In 1943 the Cardinals won 105 games and another pennant, in a runaway, but lost the World Series to the Yankees. Marion hit a Series home run and made the first of seven All-Star teams. The club duplicated its record in 1944: another 105 wins, another runaway pennant. That fall’s World Series was one of a kind: St. Louis vs. St. Louis. The Browns, the American League’s poor relations, won their only pennant when their draft rejects outplayed those of their rivals.

“We took the Browns very lightly, which was a mistake,” Marion recalled.5 The Browns won two of the first three games before the Cardinals righted themselves and put away the championship with three straight victories. Marion was sick the whole time with flu symptoms and a fever that reached 104, subsisting on orange juice, but he played every inning.

There was no Series MVP award then, but National League president Ford Frick and several sportswriters said Marion was the best player on the field. An Associated Press writer credited him with “seemingly impossible stops.”6 In Game Two he charged in to scoop up Mike Kreevich’s slow bouncer and record a forceout. When the Browns threatened in Game Four, Marion turned a scorching ground ball up the middle into a rally-killing double play.

While Marion was already recognized as an elite glove man, his high-profile Series performance changed the conversation. “I’ve looked at a lot of shortstops in my day,” said Connie Mack, whose days in the majors spanned nearly 60 years, “but that fellow is the best I’ve ever seen…. Of course, Honus [Wagner] was a better hitter, but I don’t think he could cover more ground than Marion.”7 Now the issue was not whether Marion was the best shortstop of his time, but whether he was the best of all time. The ancient umpire Bill Klem said he was Wagner’s equal. Braves manager Bob Coleman, who had been Wagner’s teammate, commented, “It seems humanly impossible to be better than Marion defensively.”8

Danny Litwhiler, a celebrated college coach who played left field behind Marion, marveled, “Balls would be hit that I just knew were going to be base hits, and I’d go in to make the play, and his arm would come over and grab it and give it the flip to first base. He just had fantastic hands.”9 Marion played shallow, trusting his quick reactions and long reach. He made the toughest chances look ordinary, “movin’ easy as a bank of fog,” the broadcaster Red Barber said.10

Marion accomplished all this while playing on what was, by popular acclaim, the majors’ worst infield. With the Browns and Cardinals sharing Sportsman’s Park, the everyday assault of spikes wore the grass to a nub and St. Louis’s hellish summers baked the dirt to lumpy concrete. Marion was the park’s best groundskeeper, obsessively picking up pebbles and grooming the surface around his position.

Despite Marion’s glowing reputation, it was a surprise when sportswriters named him the National League’s Most Valuable Player. He batted .267 with a .362 slugging percentage – both figures still the lowest for any MVP. RBI was traditionally the voters’ favorite stat; Marion had just 63.

It’s not as if there was no competition. The Cubs’ Bill Nicholson led the majors with 33 home runs and 122 RBIs, MVP numbers in many seasons. Marion received 7 first-place votes out of 24; Nicholson was second with 4. The point system – 14 points for a first-place vote, 9 for second, 8 for third, down to 1 for tenth – made it the closest vote ever: 190 points for Marion, 189 for Nicholson.

Nicholson’s Cubs finished fourth with a losing record. As the writers saw it, Marion was the MVP of the league’s best team. Even though Musial batted .347/.440/.549, he finished fourth in the balloting with 3 first-place votes. Catcher Walker Cooper hit .317/.352/.504 and finished eighth. His brother Mort, 22-7, 2.46, was ninth. (The writers voted before the World Series, but the results weren’t announced until November.)

Marion, the first shortstop to win the award, led the league in fielding percentage, but his .972 mark was not extraordinary. He did not lead in putouts, assists, or double plays, the other fielding statistics available in that era; Cincinnati’s Eddie Miller swept all three categories. The voters probably didn’t know any of that; fielding stats usually weren’t published until after the season. Marion won because he aced the writers’ eye test. (Modern sabermetric fielding stats, estimated from incomplete data, rate him very high.)

Owner Sam Breadon offered the MVP a $1,000 raise to $13,000. Marion wanted $15,000. Breadon, like his former deputy Rickey, was a notorious cheapskate; his club was among the lowest paying in the majors. He explained that the Cooper brothers were making $13,000 apiece and he had promised them they would be the highest-paid Cardinals. “I don’t care what the Coopers are making,” Marion said. “I won’t play for $13,000.”11 He got the $15,000 and so did the Coopers. Mort bought Marion a new hat to say thanks. Breadon called his shortstop the toughest businessman he had encountered among the players, and he meant that as a compliment.12

With only four core players left from the ’42 Swifties, St. Louis won 95 games in 1945 and wound up just three behind the pennant-winning Cubs. If not for the war, Marion believed the Cardinals could have won at least six pennants in a row.

The spring of 1946 brought renewal in baseball, but also anxiety. The war veterans had to find out whether they could still play, while the wartime replacements were struggling to hold onto their jobs. For most of the fill-ins, it was a losing battle.

Two outside forces stirred this pot of uncertainty. The Mexican League brandished suitcases full of cash to lure major leaguers to the outlaw circuit. Only a few accepted. A Boston lawyer, Robert Murphy, founded the American Baseball Guild, a union that, he asserted, would protect players from the tyranny of the owners. Murphy’s organizing drive failed, but it was a sign of the times; 1946 saw strikes in dozens of American industries as workers demanded relief from wartime wage restrictions. Even a whisper of unionization scared baseball owners into radical action: They agreed to meet with player representatives for the first time since the 19th century, to discuss their employees’ complaints.

Marion, though only 29, was worrying about his future. His chronic back problems had become so painful that the team’s trainer, Harrison “Doc” Weaver, roomed with him on the road to give him treatment. Marion called the Doc “probably the best friend I ever had in baseball.”13 Weaver, who had played tackle on coach Branch Rickey’s Ohio Wesleyan football team 40 years earlier, was old enough to be thinking of retirement. He and Marion began talking about a pension plan for ballplayers.

Neither man knew an actuarial table from a pool table, but they crafted a detailed proposal. “I discussed the pension plan with Doc Weaver at great lengths most every day,” Marion wrote, “and as I would talk Doc would put it down on paper.”14

National League player representatives chose Marion, Dixie Walker, and Billy Herman as their delegates to the August meeting with owners. The player reps from both leagues asked for, among other things, a guaranteed minimum salary; an expense allowance for spring training (their paychecks didn’t start until Opening Day); expanded postseason barnstorming, an important source of extra income; and a pension plan.15

The owners, likely stifling smug smiles of relief, granted most of these modest requests, too modest to be called demands. The sportswriter Red Smith scoffed that the owners were “tossing the help a bone” and ridiculed players who thought they were getting steak.16

The player reps didn’t raise the issue of the reserve clause that prohibited them from playing for the team of their choice. Marion said later, “We didn’t think baseball could operate without the reserve clause.”17 They also knew that troublemakers could be released or demoted to the minors with no right of appeal. But the package of changes, meager as they were, added up to the greatest concession by owners in the history of professional baseball.

After actuaries ran the numbers, owners and players adopted a pension plan that provided $50 a month at age 50 for a player who had spent five years in the majors and $100 for a 10-year man. (Those who waited until they were older got bigger checks.) The plan was funded by contributions from players and owners plus a share of broadcasting rights fees for the All-Star Game and World Series. That was very close to Marion’s original proposal.

The pension became the players’ prize benefit and a continuing source of friction with the owners. Twenty years later, when Marvin Miller was elected executive director of the Players Association, he found that the pension plan was the members’ number one concern. As big TV money swelled the fund, the ballplayers’ pension grew to be the most generous outside of a corporate executive suite, although latter-day players refused to share the increases with those of Marion’s generation who had laid the foundation.

On the field, there was a pennant to be won. The 1946 National League race, again featuring the Cardinals and Dodgers, ended in a tie for the first time. St. Louis won two straight games to take the best-of-three playoff and defeated the Red Sox in the World Series for the Cards’ third championship in five years. In Marion’s later years, when anyone asked him how it felt to win a World Series, he would say, “Just like Christmas.”18

Marion faced a challenge off the field during the World Series. Several of the Red Sox didn’t want to give up a portion of their Series money to seed the new pension fund. Marion went into the opposing team’s clubhouse to try to persuade them to go along. Boston owner Tom Yawkey won the day by pledging to reimburse any player who felt shortchanged.

Another outsider roiled baseball in 1947. The arrival of Jackie Robinson thrust Marion and his teammates into the role of racist villains in the integration drama. The New York Herald Tribune reported that some of the Cardinals had planned to strike rather than play against Robinson and the Dodgers but backed off after NL president Ford Frick threatened to suspend them. While the Tribune writer, Stanley Woodward, named no names, he blamed the team’s many southerners – “boys from the Hookworm Belt” – for fomenting a strike.19

Other writers have fingered Enos Slaughter, Terry Moore, Harry Walker, and Marion as possible ringleaders. In the decades since, every Cardinal who was asked has denied that there was a plot to strike, although several acknowledged some angry talk. There is no hard evidence that any plot existed.20

Marion always insisted he knew nothing of a strike threat: “I never heard such a stupid thing in my life.”21 A few years later Robinson himself wrote that Marion “was always nice to me.” He remembered one incident when he slid hard into Marion and the shortstop helped him up and asked if he was okay.22

St. Louis reeled off three straight second-place finishes from 1947-1949, coming within one game of the pennant in ’49. But the Swifties were aging, and the farm system was no longer churning out quality replacements. They dropped to fifth in 1950. Marion suffered torn cartilage in his right knee during spring training and played only 106 games. The injury effectively ended his career at 33, bringing the reign of Mr. Shortstop to a premature close.

Manager Eddie Dyer was forced out, and the club’s new owner, Fred Saigh, named Marion to replace him. Some of the players thought the job should have gone to Terry Moore, their former captain who was now a coach. Marion had impressed Saigh, just as he had won Sam Breadon’s respect, with his personality and intelligence.

The 1951 Cardinals were dragged down by injuries and a flu outbreak that tore through the clubhouse. Marion, after knee surgery, couldn’t play at all. His team finished 81-73, in third place but 15 ½ games behind the Giants, who won the pennant with “The Shot Heard ’Round the World.” Marion riled Saigh by spending his days off with his family and business interests instead of talking to the owner about how to improve the club. Saigh fired him at the end of the season, citing poor communication.

Marion didn’t have to leave home for his next job. Bill Veeck, scuffling to keep his failing Browns afloat, was surrounding himself with ex-Cardinals in the vain hope that they would pull in some customers. He hired Rogers Hornsby as manager, Harry Brecheen as pitching coach, and Marion as a player-coach. The 35-year-old Marion got into 67 games in 1952, but he was clearly finished.

By June the players were in near-revolt against the foul-tempered manager. Veeck fired Hornsby and turned the club over to Marion. The Browns got even worse under their new leader. A 62-90 record left them in seventh place.

The American League blocked Veeck’s attempt to move his bankrupt franchise to Baltimore. Veeck’s fellow owners wanted to get rid of him and his fan-pleasing stunts and his “socialistic” idea that all teams should share local TV money. News of the proposed move alienated the Browns’ few remaining fans. Marion stayed on to preside over a team that lost 100 times in 1953 and fell to last place in attendance and the standings.

As soon as Veeck agreed to sell, AL owners approved the Browns’ transfer to Baltimore. But Marion didn’t survive the move. He told the new general manager, Arthur Ehlers, exactly how bad the club was, and Ehlers fired him for his “defeatist” attitude.23 The new Orioles proved their old manager right; they lost 100 again in 1954.

Marion’s reputation did survive the train wreck that was the St. Louis Browns. He quickly found work as a coach with the Chicago White Sox in 1954, where he stepped into a three-cornered feud. Sox manager Paul Richards was growing fed up with general manager Frank Lane’s second-guessing. Lane was growing fed up with the meddling of Chuck Comiskey, the 29-year-old grandson of the team’s founder, who thought he should be running the show.

In three years, Lane and Richards had turned a perennial loser into a consistent winner, but their partnership was fraying. Hiring Marion was Lane’s decision, not Richards’. To create an opening on the coaching staff, Lane fired one of Richards’ cronies, Doc Cramer. Marion looked like a manager in waiting.

He didn’t have to wait long. Richards quit in September to take a better job as both manager and general manager of the Baltimore Orioles. Marion managed the last nine games for a club that finished third with 94 wins. Lane followed Richards out the door a year later, leaving the Comiskey heir in charge – as long as he didn’t upset his mother, who controlled the checkbook.

Under Marion the White Sox stalled in third place in 1955 and 1956. Chuck Comiskey announced that the manager would return for another year. That promise was soon forgotten as Marion found himself playing the part of Rick Renteria, with Al Lopez as Joe Maddon.24

Lopez was the only manager to interrupt the Yankees’ string of pennants from 1949-1956, when his Cleveland Indians won in ’54. He resigned after the Indians finished second in ’56, and Comiskey grabbed him, dumping Marion in the ditch.

“I don’t think the club could have done better than it did this year,” Marion said, “but I am willing to step aside to let somebody else see if he can do better.”25 He walked away with the $30,000 he was owed for 1957. Years afterward he reflected on the job of a manager: “You give me the players, I’ll win my share. You give you the players, you’ll win your share. The hardest thing about managing is keepin’ ’em happy.”26

Marion, only 40, set his sights higher. Among his offseason jobs during his playing career, he had sold printing services for a St. Louis company owned by Milton Fischmann, a rising business leader about his age. The two became friendly and eventually neighbors in suburban Ladue. With Marion as the front man and Fischmann as the money man, they put together a group of investors in 1957 to buy the Minneapolis Lakers of the National Basketball Association. The sale fell through, and the Lakers later moved to Los Angeles.

Turning to more familiar ground, Fischmann and Marion bought the Houston Buffs, a longtime Cardinals farm team that was joining the Triple-A American Association in 1959. At a press conference, Marion announced that he would move to Houston as president of the club. He went home to find Mary and their four daughters sobbing at the thought of leaving St. Louis. Daddy had to buy the girls a poodle to restore peace in the household, and he became a long-distance commuter.

Fischmann and Marion were positioning themselves to break into the majors. Houston was widely recognized as a leading candidate for an expansion franchise. With no timetable for expansion in sight, the partners bid for the Kansas City Athletics after the club owner, Arnold Johnson, died in 1960. They lost out to Charles O. Finley.

That same year the National League voted to put new teams in Houston and New York. But the league passed over Fischmann and Marion, and awarded the Houston franchise to a syndicate headed by Texaco heir Craig Cullinan Jr., oilman R.E. Smith, and Judge Roy Hofheinz, a local political power broker. Although Marion believed Hofheinz’s grand plan for a domed stadium was the deciding factor, the Cullinan group had been laying the groundwork for a big league team for nearly a decade.

Marion had renewed his ties with the Cardinals, serving as a spring training coach after his friend Bing Devine became general manager. When the team moved into the new Busch Stadium in 1966, Marion became part owner and manager of the Stadium Club, an upscale members-only restaurant. He ran the club for 18 years before retiring.

Marion drew a high of 40 percent in 1970 in the sportswriters’ voting for the Hall of Fame, far short of the 75 percent needed for election. He lived to see himself eclipsed as the shortstop on the Cardinals’ all-time teams by the Wizard, Ozzie Smith. Marion died of an apparent heart attack at 94 on March 15, 2011. He left behind Mary, his wife of 73 years, and daughters Martinna, Virginia, Linda, and Nancy.

According to his family, Marion “ enjoyed duck hunting, fishing, farming, driving Cadillacs, smoking cigars, and being in the outdoors all with his friends, his daughters, and their families. Most of all, he enjoyed being with Mary.”27

Notes

1 Red Smith, “Orioles’ Ehlers Didn’t Want Truth from Marty Marion,” syndicated column in the Washington Post, November 13, 1953, 33.

2 William Gildea, “Around Camden Yards, Ripken is Toasted with Cheers,” Washington Post, September 6, 1995, B7.

3 “Marty Marion Dies; Shortstop Was MVP with ’44 Cards,” stltoday.com, March 16, 2011.

4 Baseball encyclopedias give his birth year as 1917, but his gravestone and the Social Security Death Index say 1916.

5 Marty Marion interview by Walter Langford, May 10, 1985, SABR Oral History Committee.

6 “Cardinals Win in 11th, 3-2,” Associated Press-Baltimore Sun, October 6, 1944, 14.

7 Frederick G. Lieb, “Hats Off!” The Sporting News, October 12, 1944, 8.

8 Daniel W. Scism, “Sew It Seams,” Evansville Courier and Press, October 15, 1944, 2. The column’s title may be the lamest pun in the pun-littered history of American journalism.

9 Peter Golenbock, The Spirit of St. Louis (New York: Harper Entertainment, 2000): 255.

10 Red Smith, “Views of Sport,” syndicated column in the Dover (Ohio) Daily Reporter, October 6, 1966, 20.

11 William B. Mead, Baseball Goes to War (repr. Washington: Broadcast Interview Source, 1998): 16. (Originally titled Only the Browns).

12 William Marshall, Baseball’s Pivotal Era: 1945-1951 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1999): 75.

13 Marty Marion, letter to James T. Gallagher, April 24, 1964, in Marion’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York.

14 Ibid.

15 The American League player representatives were Joe Kuhel, Johnny Murphy, and Mel Harder. The full list of the players’ proposals is in Marshall, Baseball’s Pivotal Era, 77-78.

16 Red Smith, syndicated column, July 31, 1946, reprinted in Red Smith on Baseball (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2000): 10.

17 Marshall, 78.

18 Obituary, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 18, 2011, GenealogyBank.com, http://genealogybank.com/doc/obituaries/obit/1360D5CE1FBA19D0-1360D5CE1FBA19D0. Accessed November 12, 2015.

19 Woodward’s stories were reprinted in The Sporting News, May 27, 1947, 4.

20 For accounts of the alleged strike threat, see Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment (New York: Vintage, 1984); and Marshall, Baseball’s Pivotal Era.

21 Golenbock, 384.

22 Jackie Robinson, “A Kentucky Colonel Kept Me in Baseball,” Look, February 8, 1955, 87.

23 Red Smith, “Orioles’ Ehlers Didn’t Want Truth.”

24 In 2014 the Cubs announced that Renteria would return as manager, then fired him when the highly esteemed Maddon became available.

25 “Comiskey Lists Lopez as Prospect,” Associated Press, October 26, 1956. Clipping in Marion’s HOF file.

26 Larry Moffi, This Side of Cooperstown (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1996): 9.

27 Obituary, St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Full Name

Martin Whiteford Marion

Born

December 1, 1916 at Richburg, SC (USA)

Died

March 15, 2011 at Ladue, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.