Allan Travers

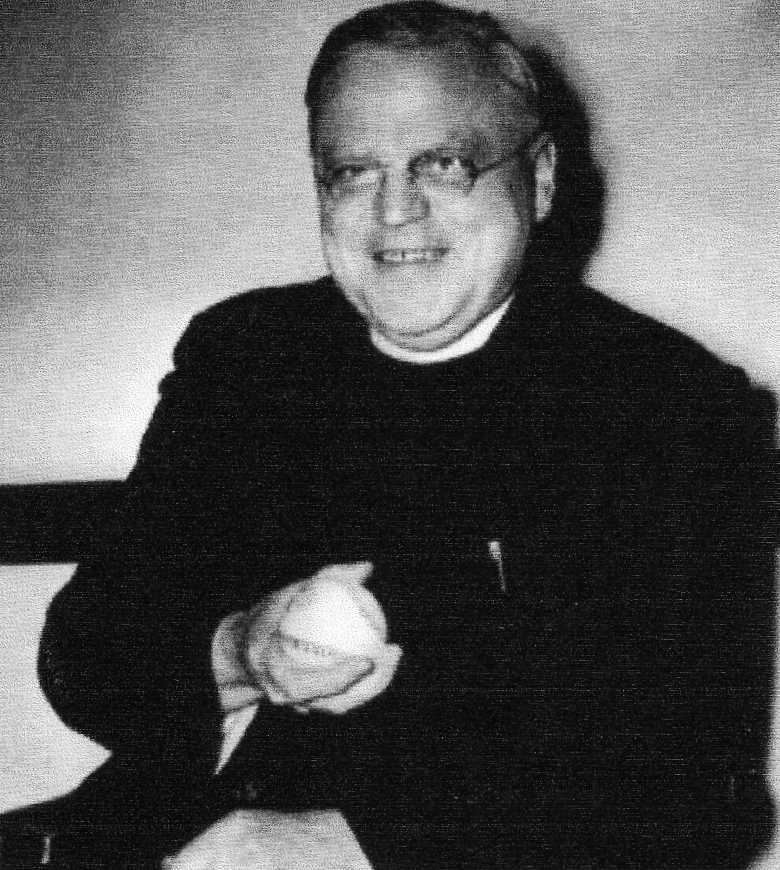

Through an extremely unlikely, almost unbelievable set of circumstances, a twenty-year-old college junior with virtually no baseball experience and little athletic ability found himself on the pitcher’s mound one bright, sunny Saturday afternoon facing the World Champion Philadelphia Athletics. The date was May 18, 1912–surely one of the most bizarre days in major league history–and the site was Shibe Park, Philadelphia. The pitcher was Allan Travers, a student at nearby St. Joseph’s College. A few years later, he would become Father Aloysius S. Travers, S. J., and to this day he is the only Catholic priest ever to play in a major league game.

Through an extremely unlikely, almost unbelievable set of circumstances, a twenty-year-old college junior with virtually no baseball experience and little athletic ability found himself on the pitcher’s mound one bright, sunny Saturday afternoon facing the World Champion Philadelphia Athletics. The date was May 18, 1912–surely one of the most bizarre days in major league history–and the site was Shibe Park, Philadelphia. The pitcher was Allan Travers, a student at nearby St. Joseph’s College. A few years later, he would become Father Aloysius S. Travers, S. J., and to this day he is the only Catholic priest ever to play in a major league game.

On the previous Wednesday, May 15, the sixth-place Detroit Tigers were in New York’s Hilltop Park for a regularly scheduled game against the New York Highlanders. As the game started, no one could possibly imagine that it would become the infamous game in which an enraged Ty Cobb savagely beat an abusive, handicapped fan named Claude Lueker. On this fateful day he had been taunting Cobb with a steady barrage of profanity-laced abuse peppered with racial slurs.

Cobb stormed into the stands and battered Lueker with a vicious volley of punches to the face, and then stomped him in the abdomen with his spikes. Unknown to Cobb was that Lueker, a former pressman, had lost one complete hand and three fingers from the other hand in an industrial accident the previous year. With fans screaming at Cobb, “Don’t hit him! He has no hands!” the out-of-control Cobb reportedly shouted back, “I don’t care if he has no feet!”

Unfortunately for Cobb, American League president Ban Johnson was in the park that day. He had witnessed the horrific incident and was aghast, later informing Detroit manager Hughie Jennings that Cobb was hereby suspended indefinitely. After the next game on Friday in Philadelphia, sixteen Tiger players voted to strike in protest of Cobb’s suspension. They would not take the field again, they declared, until Cobb was reinstated.

Ban Johnson was not easily intimidated. Aware of the threatened walk-off, he informed Detroit’s owner Frank Navin that the team would be fined $5000 and forfeiture for every game that he failed to field a team. Navin panicked. Not one to call Johnson’s bluff and sensing that the team was serious about the walk-off, he knew he was in critical danger of losing his franchise. He ordered Jennings to field any team he could find. Philadelphia manager Connie Mack suggested drafting a team of substitutes from around Philadelphia. That sounded reasonable, so Jennings sought help from a Philadelphia acquaintance, Joe Nolan, sports writer for The Philadelphia Bulletin.

During the spring exhibition season, the Philadelphia Athletics had fielded a team of second stringers called the “Yannigans” against the nearby St. Joseph College varsity baseball team. Nolan was acquainted with the team’s assistant manager, Allan Travers, a twenty-year-old junior from Philadelphia. Before the Saturday afternoon game, Nolan contacted Travers asking him to find ten to or twelve amateurs in case the Tigers went through with their threatened strike. Nolan informed Travers that the recruited group would not be expected to play in the game, but were only required to take the field.

Travers agreed to Nolan’s arrangement and recruited eight potential “Tigers” from his 21st and Lehigh neighborhood in North Philadelphia. Each participant would be paid $25. The players Travers recruited included six “sandlotters” and two Philadelphia area amateur boxers: Dan McGarvey, 25; Jim McGarr, 24; Pat Meaney, 20; John Coffey, 19 (who played that day using the alias Jack Smith); Hap Ward, 20; Ed Irvin, 20, Bill Leinhauser, 19, and Billy Maharg, 29. McGarvey and McGarr had been teammates at Georgetown College; the boxers were Maharg and Leinhauser, a noted amateur welterweight. This unlikely group arrived at Shibe Park early and, as instructed by Jennings, took seats in the bleachers. Navin demanded a replacement team to take the field, and Jennings was prepared to deliver. As the 2:30 PM game time neared, a surprising crowd of over 20,000 Philadelphia fans had packed into the park on a bright, sunny afternoon.

Umpire Bill Dineen called “Play Ball,” and the Tiger regulars in their traveling grays took the field. Ty Cobb sheepishly strolled out to his customary spot in center field until umpire Ed “Bull” Perrine waved him off. Cobb stalked off the field with the Tigers following behind. They returned to their clubhouse and removed their uniforms. The first ever players’ strike in the major league baseball history was on. Now it was Jennings’ turn to act. He signaled for Al Travers and the other “misfits” to come into the clubhouse and donned the uniforms of the striking Detroit players. All hurriedly signed standard one-day contracts and were now officially “Tigers.”

Seeing the large crowd and fretting over the potential loss of substantial revenue, Connie Mack had a sudden change of heart. He now insisted that the game be played. Why cancel the game, Mack reasoned, when his team had an opportunity to fatten their individual statistics? Jennings was stunned, but he could not find it within himself to challenge a decision of saintly Connie Mack. He instructed his shocked recruits to take positions on the field. He recruited two of his own Detroit coaches for the game: ancient Jim “Deacon” McGuire, now 48, a former catcher who consented to fill in behind the plate; and white-haired Joe Sugden, 41, for first base. McGuire was completing an astonishing twenty-six-year major league career in which he had played with twelve different teams. Sugden had been inactive as a player for over seven years.

The next problem was to find a pitcher. Enticed by the $50 fee offered by Jennings, Travers volunteered, even though he later confessed that he had never pitched a game in his life. The revamped Tigers, with Al Travers ready to take the mount, awaited the start of the game against the World Champion Athletics.

Travers, the principal player in this unlikely drama, was not a natural athlete. Born on May 7, 1882, he claimed to have played some stickball in his youth, but his mother had dreamed of him becoming a musician for the Philadelphia Symphony Orchestra. Now in his junior year at St. Joe’s, he was following his mother’s wishes by playing violin in the student orchestra. He was also an actor of some promise and performed in the school Oratorio society. Not talented enough to make the varsity baseball team, his duties as assistant manager included writing up summaries of each game for the school annual–hardly a glowing resume for a potential major leaguer. What was going through the mind of young Travers as he strode to the mound that day? Did he know what awaited him? One day he’s at St. Joe’s College innocently attending his classes…and the next, by a strange quirk of fate, he’s on the mound pitching in a major league game in front of 20,000 fans.

To make matters worse, the powerful A’s treated the game like the seventh game of the World Series, as Connie Mack turned the tables on the naive Jennings and fielded his regulars. The famous “$100,000 infield” of Hall-of-Fame third baseman Frank “Homerun” Baker, acclaimed shortstop Jack Barry, Hall-of-Fame second baseman Eddie Collins, and the great defensive first baseman Stuffy McInnis played the entire game. In centerfield was standout Amos Strunk. Two of the three pitchers were aces: Jack Coombs and Hall-of-Famer Herb Pennock. They combined with Boardwalk Brown for 16 strikeouts. Led by the competitive Collins, the A’s never let up, with eight stolen bases, four doubles, and seven triples.

What may have started as a thrill for the replacement players quickly turned into an embarrassing farce. As expected, the A’s won handily, 24-2, with Travers allowing all 24 runs on 26 hits, walking seven, and striking out one. The score was a respectable 6-2 through four innings until the A’s erupted for 16 runs over the next three innings. Travers’ lifetime ERA was 15.75 for his one-day “career.” He unwittingly set a major league record for most runs allowed in a nine-inning game that exists to this day. The only recruit to get a hit was Ed Irvin, going 2-3. The crowd viewed the game as a joke, and after the third inning many left in disgust, seeking a refund of their money. Fortunately, there were no serious disruptions during the game, and the players were escorted off the field by local police. By the end, the weary players knew they had been used and had participated in a travesty.

The next day was Sunday, which in those days meant no baseball, but Johnson immediately canceled Monday’s game and then called a mandatory meeting with the striking Detroit players. Johnson informed them in no uncertain terms that if the strike continued another day, they would all be banned for life. They had been read baseball’s version of the proverbial “riot act.”

The Tigers then departed for their next series in Washington. In a rare act of humility, Ty Cobb advised his teammates not to jeopardize their careers and urged them to end the strike. Ban Johnson’s threat had its intended effect as the Tigers meekly returned to the field the following day. The one day walk-off was over. Each striking Tiger received a $100 fine, while Cobb, the instigator of the entire sordid affair, was fined only $50. Surprisingly, Johnson reduced Cobb’s suspension to ten days, retroactive to May 16, and so he was back in action on May 26. Perhaps Cobb’s threat to sue Major League Baseball helped his cause.

To his friends Al Travers was a celebrity that day, but his mother was not pleased. The next morning she saw a picture of him in the newspaper with the caption: “strikebreaker.” There was concurrently a trolley strike in Philadelphia that month, and his mother feared for his safety from vengeful “hooligans.”

Following graduation in 1913, Travers entered The Society of Jesus and studied at St. Andrew on the Hudson in New York, and Woodstock College in Maryland, from where he was ordained into the priesthood in 1926. He subsequently taught at St. Francis Xavier High School in Manhattan for eight years and then was named Dean of Men at St. Joseph’s College in 1939. In 1943, he returned to his alma mater, St. Joseph’s Prep, and taught Spanish and religion for 25 years until his death in 1968. He became known as the “Man who saved the Detroit franchise,” not to mention the only priest ever to play in a major league game.

Father Travers was always reluctant to talk about his one day of fame, perhaps finding the entire episode embarrassing. Kevin Quinn, currently Associate Athletic Director at Saint Joseph’s University, was a student of Father Travers in the 1960s at St. Joe’s Prep, and confirms this impression: “He never spoke of the game, even when he would be asked. The ‘asking’ was done by one of the ‘wise guys’ in almost a taunting way and Father Travers never acknowledged his role.”

Years later, Father Travers broke his silence in an interview with Red Smith, giving his account of that crazy day in 1912:

About noon when Nolan told me about the strike of the Detroit players he told me the club would be fined and might lose its franchise if twelve players didn’t show up. He told me to round up as many fellows as I could find, so I went down to 23rd and Columbia where a bunch of fellows were standing around the corner. We thought we’d just go out and appear. We never thought we’d play a game.

About his pitching he said:

I was throwing slow curves and the A’s were not used to them and couldn’t hit the ball. Hughie Jennings told me not to throw fast balls as he was afraid I might get killed. I was doing fine until they started bunting. The guy playing third base had never played baseball before. I just didn’t get any support…no one in the grandstands was safe! I threw a beautiful slow ball and the A’s were just hitting easy flies…trouble was, no one could catch them.

Less is known about the other replacement players. Bill Leinhauser, who had the thankless task of replacing Cobb in center field, served in France during World War I and later became a Philadelphia police detective for 41 years, 29 in narcotics. A rumor making the rounds in 1912 was that when his wife found that he had the audacity to replace the great Ty Cobb, she hit him with a skillet. He survived until 1978. The shadowy Billy Maharg would resurface seven years later as a gambler, fixer, and informer in the notorious 1919 Black Sox scandal. He was the only one who made it legitimately to the Majors, with one at-bat for the Phillies in 1916. He died of unknown causes in 1953. Ed Irvin died from injuries suffered when, according to The Baseball Necrology, he was “thrown through a saloon window” in 1916; Pat Meaney died from a combination of unknown illnesses in 1922; John Coffey would survive until 1962; Hap Ward until 1979; Jim McGarr until 1981. The entire episode was a precursor to future attempts in baseball to organize labor unions.

By playing in this game, the “misfits” unwittingly became a small piece of baseball’s storied lore, with their names and “career” statistics eternally etched into the pages of baseball history. In baseball’s bible, the venerable Baseball Encyclopedia, along with immortals like Babe Ruth, Lou Gerhig, Ted Williams, Walter Johnson, and Cy Young, we find…Aloysius Travers?…Hap Ward? How many people, randomly thumbing through their encyclopedias over the decades, have ever noticed these obscure names? How many would ever associate them with that bizarre day in 1912 when a future priest, five “sandlotters,” and two amateur boxers became major leaguers for a day?

Sources

Alexander, Charles C. Ty Cobb. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984.

Davis, Ted. Connie Mack. Lincoln, Nebraska: Writers Club Press, 2000.

Gay, Timothy. Tris Speaker. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2005.

Lee, Bill. The Baseball Necrology. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 2003.

Light, Jonathan Fraiser. The Cultural Encyclopedia of Baseball, Second Edition. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 2005.

Reichler, Joseph. Baseball Encyclopedia. New York: Macmillan, 1993.

Stein, Harry. Hoopla. New York: Dell Publishing, 1983.

Stump, Al. Cobb. Chapel Hill, North Carolina : Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 1994.

“The Fans Speak Out,” Baseball Digest, May 2007, p. 9. (Letter from Gary L. Livacari, Box Score of Tigers-Athletics game of May 18, 1912)

New York Times, May 19, 1912.

Philadelphia Inquirer, April 25, 1968.

St. Joseph’s College Annual, 1913.

Special thanks to:

- Fr. Timothy R. Lannon, S.J., President, Saint Joseph’s University

- Ms. Pat McAvinue, Director, Saint Joseph’s University Archives

- Mr. Don DiJulia, Athletic Director, Saint Joseph’s University

- Mr. Kevin Quinn, Associate Athletic Director, Saint Joseph’s University

- Ms. Marie Wozniak, Assistant Athletic Director, Saint Joseph’s University

- Mr. Ken Krsolovic, Athletic Director, Lake Erie College

Full Name

Aloysius Joseph Travers

Born

May 7, 1892 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

Died

April 19, 1968 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.