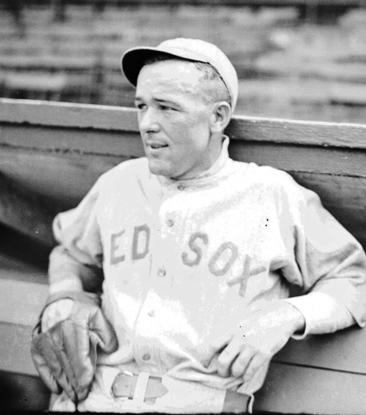

Walt Kinney

July 1918 was perhaps the most momentous month in Walt Kinney’s life. The Texas League – like all minor leagues during the summer of 1918 – had been facing dwindling attendance and a steady stream of young players leaving for the Great War in Europe, or accepting war-related employment. Finally, on July 7, the league canceled the remainder of its season. Kinney, a left-handed pitcher for the Dallas Giants, returned to his home in Denison, Texas.

July 1918 was perhaps the most momentous month in Walt Kinney’s life. The Texas League – like all minor leagues during the summer of 1918 – had been facing dwindling attendance and a steady stream of young players leaving for the Great War in Europe, or accepting war-related employment. Finally, on July 7, the league canceled the remainder of its season. Kinney, a left-handed pitcher for the Dallas Giants, returned to his home in Denison, Texas.

On July 12, Kinney’s wife, the former Jessie Elizabeth Ringo, gave birth to their first child, Walter Jr. A couple of days later, Kinney’s contract was purchased by the Boston Red Sox and the 24-year-old pitcher headed north to Chicago to join his new teammates. On July 26, he made his major league debut at Comiskey Park.

Kinney appeared in only five games for the 1918 Red Sox, pitching a total of 15 innings. He was not on the team’s World Series roster, but he did serve as a batting practice pitcher. He later pitched parts of three seasons for the Philadelphia Athletics.

Walter William Kinney was born in Denison, Texas, on September 9, 1893, to John William Kinney and Cora Estelle Sabin. Kinney’s maternal grandmother was the daughter of Ezra Chandler and Louisa Ann Kendall. One of Ezra’s brother’s descendants was Albert Benjamin “Happy” Chandler, commissioner of baseball from 1945 until 1951.

Kinney first pitched professionally at the age of 20 for the Denison Railroaders in the Texas-Oklahoma League in 1914. In 27 games, he pitched 187 innings, allowing 123 hits and 57 walks, while striking out 112 batters. It is not known how many of the 58 runs Kinney allowed were earned, but his runs against average was 2.79.

On February 20, 1915, Kinney, then 21, married Jessie Ringo, a 27-year-old native of Texas.

Kinney had two more good seasons with Denison (a 1.94 ERA in 210 innings in 1915 and a 2.48 ERA in 269 innings in 1916). In 1916, he first exhibited the control problems that would plague him for most of his professional career. In 269 innings, he walked 154 – an average of 5.2 per nine innings. He did win 22 games against 11 defeats, however, and that may have earned him the opportunity to finish that season out west, appearing in 16 games for Oakland in the Pacific Coast League. In 54 innings, Kinney allowed a whopping 62 hits and 38 walks. He had an 0-6 record to go along with a 4.17 ERA.

The following year, Kinney was in the Western Association, pitching for Muskogee. He led the league in several categories: innings pitched (an astonishing 370), walks (191), and strikeouts (260). He posted a 23-16 record, with 30 complete games. Again, the number of earned runs allowed is not known, but Kinney’s RA was 3.72.

Kinney was pitching for Dallas in the Texas League in 1918 – 17 games, 11 complete games, a 2.97 ERA in 112 innings, with more walks (51) than strikeouts (40) – when the league suspended its season.

The United States entered the Great War in April 1917 and Kinney registered for the draft two months later. His paperwork states that he was blind in one eye. Kinney’s niece, Marjorie Sherrill, is unsure if Kinney was actually blind in one eye or he was trying to get out of military service. Sherrill says that Kinney did have eye trouble much later in his life. The Boston newspapers made no mention of any possible issue with Kinney’s vision.

When Kinney hooked up with the Red Sox, his first days with the team were spent serving as a batting practice pitcher, along with right-hander Dick McCabe. He struck up a friendship with another lefty on the team, Babe Ruth. At 6-foot-2, Kinney and Ruth were the tallest men on the team, but that wasn’t all they had in common. Both men shared a love of pranks, crude jokes, and generally adolescent behavior. They would often box, wrestle, and carry on like two hyperactive kids.

On July 26, at Comiskey Park, the White Sox battered Red Sox starter Sam Jones for five runs in the third inning and two more in the fourth. As Boston was coming up to bat in the top of the fifth inning, an announcement was made that the War Department had granted all major league players an extension: They now had until September 1 to comply with the government’s “work-or-fight” order (a May 1918 decree that all draft-age men had to find war-related employment or become eligible for the draft).

A bit later in the game, Boston manager Ed Barrow went to his bench. Kinney relieved Jones and pitched the final four innings. He allowed only one hit, while striking out one batter and hitting another. He went 0-for-2 at the plate. Cuban-born Eusebio Gonzalez also made his big-league debut, taking over at shortstop for Everett Scott.

On August 2, exactly one week after his debut, Kinney pitched three perfect innings in Cleveland against the Indians, the Red Sox’ main rival in the pennant race. Only one ball was hit out of the infield.

As the Red Sox continued their western road trip, Kinney saw action in Detroit on August 7, giving up three hits and three runs in three innings. During his stint on the mound, Kinney and Ty Cobb got into a shouting match when the Tigers star accused Kinney of trying to bean him. After walking Cobb to load the bases, Kinney surrendered a triple to Bobby Veach. The Tigers won the game, 11-8.

Two weeks later, the Red Sox were back home, getting set for another big series with Cleveland. Kinney made his first appearance at Fenway Park on August 20, coming out of the bullpen after Babe Ruth had been shelled. Kinney pitched two innings, allowing one hit and one walk, while striking out two. The Red Sox lost the game, 8-4.

(Two days earlier, a bunch of Red Sox bench warmers and a few regulars played a Sunday exhibition game in New Haven, Connecticut. Kinney and Bill Pertica pitched for Boston, which lost to the locals, 4-3.)

During the last weekend of the regular season, Kinney appeared in two games. On August 31, he hurled three innings against Philadelphia in the second game of a doubleheader. He allowed only one hit, but walked three. Boston lost the game, 1-0, as A’s pitcher John Watson pitched two complete games that day. Carl Mays had done the same thing for the Red Sox in a twin bill the previous day.

In New York, on September 2, in the late innings of the season’s final game, Barrow made numerous substitutions. Kinney ended up playing right field.

In his 15 innings, Kinney allowed six hits, walked eight and struck out six. His ERA was 1.80 and opposing hitters batted only .147 against him. Although he did not receive a decision in any of his five games, the Red Sox lost all five. As a batter, he was 0-for-5.

Kinney and the rest of the Red Sox left New York by train and headed straight to Chicago for the World Series. Because the Cubs would be relying heavily on their two left-handed pitchers, Jim Vaughn and Lefty Tyler, Barrow wanted Kinney to pitch batting practice, to get the Boston hitters more accustomed to southpaw deliveries.

Kinney’s star turn on the 1918 Red Sox was not on the playing field. Rather, it occurred on the train ride back to Boston after the first three games of the World Series. Boston had defeated the Cubs in the first and third games and Babe Ruth – who had thrown a complete game, 1-0 shutout in the opener – was set to take the Fenway mound for Game Four.

The team’s train hadn’t even pulled out of Chicago on Saturday evening, September 7, a few hours after Game Three, when Ruth, Kinney and a few other players began racing through the cars, grabbing every straw hat they could find and ramming their fists through them. Game Four was set for Monday the 9th – Kinney’s 25th birthday – and he and the Babe apparently started celebrating a little early.

As the train traveled through western Massachusetts, Ruth somehow injured his pitching hand. The first accounts of what happened were not exactly consistent.

Boston Herald and Journal:

Babe Ruth . . . narrowly escaped serious injury on the baseball special outside of Springfield last night. He was standing in the aisle of the Sox car, talking to Carl Mays, when the train lurched, sending the Colossus aspinning and crashing against a window. The heavy glass was shattered and fell clattering, inside and outside. Babe did not know how seriously he had been injured, but he had the presence of mind not to put out his hands, and was fortunate enough to escape with only a small cut in his trousers.

Boston Traveler:

A slight accident made its appearance in the Sox camp on the way home from the middle West. Saturday night Babe Ruth was walking out of the smoker when the train gave a lurch and he was thrown against the side of the car. He put out his left to save himself from a fall and bent the third finger of his left hand so far that the middle joint was slightly strained. It swelled a little, but [team trainer] Doc Lawler was on the job with iodine and it isn’t in any serious condition this morning.

One of the Boston papers – the American – and the Chicago Herald and Examiner came a little closer to the truth. American:

Battering Babe Ruth did bump one of his pitching fingers “fooling” on the train, but the digit was not affected badly enough to harm his hurling ability.

Herald and Examiner:

[L]ast night Ruth put his pitching hand on the bum. Babe made a playful swing at a brother athlete in the smoking room of the Pullman. The brother athlete dodged and Babe bent the third finger on his left hand.

When Barrow learned what had happened, he was livid, but Ruth assured him that he could still pitch the fourth game. Babe did well in the game, though he needed some relief help from Joe Bush in the eighth inning. Boston won the game 2-1; the two Red Sox runs scored on Ruth’s fourth-inning triple.

Afterwards, the Big Fellow confessed he had been in pain for the entire game. “I still don’t know how I did as well as I did,” Ruth said. “I was lucky to get that far.” Once the victory was secure, giving the Red Sox a 3-1 lead in the series, Edward Martin could inform the Globe’s readers that Ruth’s hand “was bruised during some sugarhouse fun with W.W. Kinney”.

The Red Sox beat the Cubs in six games to win an unprecedented fifth World Series championship. It was the third title in four years for the Red Sox, and the fourth in seven years. Kinney was awarded a partial winner’s share of $300.

On Sunday, October 13, 1918, just over one month after the World Series, Kinney pitched an exhibition game for the Tulsa Federals in Cleveland, Ohio. Washington Senators ace Walter Johnson pitched for the Cleveland team and Jim Thorpe (an outfielder with the New York Giants in 1918) was scheduled to appear. The White Way Café offered to give “$10 in cash to the first player to knock a home run” in the game. An ad for the game states:

In the game at Oilton last Sunday Johnson

Beat Kinney 1 to 0 in a ten-inning game,

Kinney desires another opportunity to defeat

The peerless pitcher Johnson.

Major league baseball was considering canceling the entire 1919 season, but the Great War ended on November 11. Released after the season, Kinney signed with the Philadelphia Athletics.

In 1919, Kinney split his time between the starting rotation and the bullpen, appearing in a team-high 43 games (two fewer than the league leader). He led the AL with 21 games finished; a former 1918 Red Sox teammate, Jean Dubuc, led the NL with 22.

In 202 2/3 innings, Kinney posted a 3.64 ERA (the league average was 3.32); his nine victories were exactly one-quarter of the team’s season total. Kinney had the fourth-best rate of strikeouts per nine innings in the American League, although his lack of control was still an issue (91 walks and 97 strikeouts).

In 1920, Kinney made eight starts and two relief appearances for the Athletics before jumping the team in late May. An independent team in Franklin, Pennsylvania, had offered him $500 more than his annual salary with the Athletics.

Philadelphia manager Connie Mack tried to persuade Kinney to return to the club and the pitcher apparently told Mack he’d meet the team in Detroit. When he didn’t show up, Kinney was charged with violating his contract. According to news reports, Athletics management also had loaned Kinney $1,000 at the start of the 1920 season, in addition to giving him a 60 percent increase in salary from the previous year. When Kinney left the A’s, he still owed the club about $800.

It’s unclear how long Kinney stayed with the Franklin club, but his second child – a daughter named Mary Jean – was born in Wisconsin in September 1920. This means that after leaving the Athletics, Kinney and his family must have moved away from Texas.

The following spring, Kinney showed up at the Athletics’ spring training camp in Lake Charles, Louisiana, and asked Mack if he could rejoin the team. Mack referred him to Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who denied Kinney’s application for reinstatement on March 29, 1921, and banished him from the major leagues for five years.

Kinney was out of organized baseball for only two years. He returned to the Athletics for five games in 1923. On May 9, Kinney came out of the bullpen with the Athletics trailing the St. Louis Browns, 3-0. He helped Philadelphia tie the game in the sixth inning by hitting a home run off Urban Shocker, but then he allowed three runs in the bottom half of the inning. The Browns went on to win the game, 10-5.

Nine days later, on May 18, Kinney demanded a trade. Connie Mack refused. Kinney said he would jump the team – and he was not in uniform for the A’s game that day against Cleveland.

It turned out to be the end of Kinney’s major league career. His home run off Shocker was in his final major league at-bat.

Kinney did not play professional baseball for three years (1924-26), though he did pitch for a semipro team in Massillon, Ohio. During that time, he also did an ad for the Lonas-Nash Garage:

“While not Playing Base Ball with the Agathons he is driving his Nash. Is he satisfied with his Nash? We’ll say he is!

He traveled over 15000 miles with his NASH during December and January 1923-24 through Missouri, Oklahoma, and Texas. He changed one tire during that time, the motor is in A-1 condition without repairs or tearing down. He drove for six days through the Ozark mountain region through roads so bad that for six days he could average only nine miles per hour. He broke the road ahead of 14 other cars, making the road for all of them.

Walter Kinney’s Statement: I have driven eight different makes of cars since 1911, and will say that the NASH has given me greater pleasure and service than any other car. This leads me to believe that the NASH really DOES lead the world in Motor Car Value. Signed WW Kinney”

In 1926, Kinney, his wife, and their two children were in Orange County, California. The city directory lists his job as “ballplayer.” The following year, they had moved to a different address and Kinney was listed as a “pumper.”

Kinney resumed his baseball career in 1927, when, at age 33, he signed with the Portland Beavers of the Pacific Coast League. He had a rough year, pitching in 172 innings over 35 games, allowing 189 hits, walking 72, and striking out only 36. His ERA was 4.50.

In 1928, Kinney was again working as a laborer, although he also pitched in 38 games for the Hollywood Stars (PCL) and compiled a record of 17-8. City records again list him as a ball player in 1929 and 1930. The US Census of 1930 lists Kinney and his family as renting a house at 1040 West 4th Street in Santa Ana, California. His occupation is professional ballplayer.

Kinney pitched 13 games for Dallas (Texas League, 1930), two for Mission (PCL, 1931), and eight for Tucson (Arizona-Texas League, 1931) before finishing his baseball career in Hollywood (PCL, 1932) with just 11 innings in two games.

Kinney and his wife remained in California, though it’s not clear what Kinney did after his baseball career was over. According to Marjorie Sherrill, Kinney’s niece, at one point Kinney tried his hand at prospecting. When the Kinneys lived in Redondo Beach, California, Sherrill says, “their major entertainment was to go to the thrift store down the street on Tuesdays when a new shipment would be delivered. They were excited by some of their little finds.”

In a family history, Kinney’s grandson notes, somewhat cryptically, that Kinney “did not know how to handle so much fame and money, etc. and he ran into some difficulties.” Sherrill recalls Kinney telling her “how he was taken advantage of by flim flam men and lost money in the stock market due to his lack of education.” Neither Kinney nor his two siblings finished high school.

In his later years, Kinney had diabetes and a drinking problem. After his wife died in January 1970, he took a turn for the worse. His eldest son, Jack, put him in an assisted living home in Escondido, California, where he died on July 1, 1971.

Sources

Babe Ruth and the 1918 Red Sox, by Allan Wood (and personal research).

E-mail correspondence with, and documents provided by, Marjorie Kinney Sherrill (Kinney’s niece – her father was Walt’s older brother Carl Kinney).

Full Name

Walter William Kinney

Born

September 9, 1893 at Denison, TX (USA)

Died

July 1, 1971 at Escondido, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.