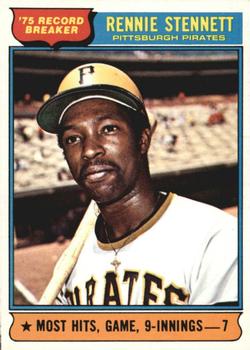

Rennie Stennett

On September 16, 1975, the Pittsburgh Pirates were wrapping up a three-game series with the Chicago Cubs at Wrigley Field. They held a six-game lead over Philadelphia in the National League East Division and the season was growing old. With only 12 games remaining on the Pirates’ schedule, time was indeed running out on the Phillies.

On September 16, 1975, the Pittsburgh Pirates were wrapping up a three-game series with the Chicago Cubs at Wrigley Field. They held a six-game lead over Philadelphia in the National League East Division and the season was growing old. With only 12 games remaining on the Pirates’ schedule, time was indeed running out on the Phillies.

The drama on the North Side was short-lived as the Pirates sent 14 men to the plate in the first inning, scoring nine runs. Rennie Stennett led off with a double to right field, and singled to right in his next at-bat, later in the frame. He scored both times. He added a single to center in the third inning, and a double to left and single to right in fifth inning when the Pirates batted around again, sending 11 men to bat. The score was 18-0 and the carnage continued. Stennett singled to center in the seventh inning and tripled to right field in the eighth. He was then lifted for pinch-runner Willie Randolph.

The final score was Pirates 22, Cubs 0. It remains the worst defeat suffered by Chicago at Wrigley Field. For Stennett, it was a record-setting day, as he collected seven hits in seven at-bats, scored five runs, and drove in two. His seven hits tied the National League record for hits in a nine-inning game, set by Wilbert Robinson of the Baltimore Orioles in 1892. Stennett also tied a record with the most times getting two hits in one inning. “I got to the ballpark and I wasn’t supposed to play that day. I had twisted my ankle and it was badly swollen,” recalled Stennett. “But I taped up the ankle and I played. The first time up I hit a ball between (Cubs) first baseman Andre Thornton and the bag, and in my mind that told me that day I was gonna do good because as a right-handed hitter, when I’m hitting the ball to the right side, I know I’m hitting good. That was a shot, and it triggered something. I felt all I had to do was make contact and I was going to get a hit.”1

Stennett told the team trainer, Tony Bartirome, to tell Pirates manager Danny Murtaugh to remove him from the game because of his ankle. But Murtaugh refused until Stennett made an out. “I came up to bat in the eighth inning for the seventh time and hit a line drive to right-center and they said (outfielder) Champ Summers could have caught it, but he dove and he missed it and I wound up with a triple.”2

“I heard that when Uncle Robbie (Wilbert Robinson) was managing, whenever any of his players got six hits, he took him out of the game,” quipped Murtaugh.3 But Stennett was not done. The next night, he got three more hits at Philadelphia to set a new mark for most hits (10) in consecutive nine-inning games. The next evening, he collected two more hits, to give him 12 hits in three consecutive nine-inning games, tying a record.

Renaldo Antonio (Porte) Stennett was born on April 5, 1951, in Colon, Panama. He grew up in the same neighborhood as Rod Carew, and attended the same high school, Paraiso, as Carew had. Stennett was a multisport athlete, excelling in volleyball, basketball, and track. He especially excelled on the hardwood; he scored a school-record 45 points in a basketball game. But baseball was his true passion. At age 15, he was a pitcher on a sandlot team; his batterymate was Manny Sanguillen. At 21 Sanguillen was already in the Pirates’ minor-league chain. Although both players hailed from Panama, there was a language barrier. Sanguillen was reared in Colon in the Republic of Panama, where Spanish is the dominant language. Stennett was raised in the Canal Zone, then a US possession, and did not speak Spanish. “I remember Rennie well,” recalled Sanguillen. “Whenever I wanted to go out to the mound to talk to him, I had to ask the third baseman to come over and translate for us.”4

At an early age, Stennett was approached by major-league teams about going to the United States. But on the advice of his father, who worked on Canal tugboats, he turned down the offers. “The Yankees, Giants, and Astros talked to me,” said Stennett. “They wanted me to come to the States to further my education. But my father wanted me to remain at home and go through high school. I’m glad I did because I don’t think I’d ever made it as a pitcher.”5

After finishing school, Stennett signed a contract with C. Herbert Raybourn, a Pirates scout in the Canal Zone area. At 18, Stennett began his ascent through the Pirates’ minor-league chain at Gastonia (North Carolina) of the Class A Western Carolinas League. He was placed in the outfield, and finished sixth in the league in hitting when he batted .288. Stennett showed a high aptitude for hitting. In 1970 at Salem (Virginia) of the Class A Carolina League, Stennett led the league in batting (.326), hits (176), and triples (9).

After the 1970 season, Stennett went to Bradenton to play in the Florida Instructional League. The conversion to second base began there, and it was a move he was welcomed. “I always wanted to be in the game and you’re in the game at second base,” said Stennett.6 When he reported to Charleston (West Virginia) of the Triple-A International League for the 1971 season, he was inserted as the starter at second base. Manager Joe Morgan was thrilled with Stennett’s progress, but wanted the youngster to work on going to his right on grounders up the middle. “He does everything else very well,” said Morgan,” and he has a whale of an arm.”7

Stennett was enjoying another terrific season at Charleston in 1971 when he was called up to Pittsburgh. Starting second baseman Dave Cash and third baseman Richie Hebner were to begin back-to-back two-week drills in the military Reserve in July. Stennett made his major-league debut on July 10, 1971, against Atlanta. On August 5, utility infielder José Pagán was hit by a pitch in Montreal and suffered a broken left arm. Although it was it an unfortunate circumstance, it opened the door for Stennett to remain in the Steel City for the remainder of the season.

Stennett’s defense at the keystone position was shaky at times and he was often replaced in the late innings for defensive purposes. But there was no denying his work with a bat. He put together an 18-game hitting streak from August 22 through September 10. It was the longest streak for a Pirate in two years. Fourteen of the games in the streak were of the multi-hit variety, as his batting average rose from .278 to .405

It was during this streak that Stennett became a part of baseball history. On September 1 Pittsburgh became the first team in major-league history to field an all-minority team to begin the game. The lineup card submitted by Murtaugh read:

- Stennett, 2B

- Gene Clines, CF

- Roberto Clemente, RF

- Willie Stargell, LF

- Sanguillen, C

- Cash, 3B

- Al Oliver, 1B

- Jackie Hernández, SS

- Dock Ellis, P

The Pirates defeated the Phillies that night, 10-7. After the game, Murtaugh was asked about the significance of his lineup. He replied, “I put the best athletes out there. The best nine I put out there happen to be black. No big deal. Next question.”8

In spite of Stennett’s contributions to the Bucs’ success, he was left off the 1971 postseason roster. Murtaugh chose to go with the veteran Pagán, who had returned to the team late in the season. The Pirates knocked off the San Francisco Giants in the NLCS, and they capped their year by winning the World Series, defeating Baltimore in seven games. After the Series, Murtaugh was moved to the front office. He had been sidelined during the year with chest pains, and the Pirates were concerned about his health. Bill Virdon, a star center fielder for Pittsburgh in the 1950s and 1960s, and the Pirates’ hitting coach since, assumed the manager job.

With Cash entrenched at second base, Stennett seemed to be a player without a position. He put in time at shortstop and at all three spots in the outfield. The 1972 season was his fourth in pro ball, so there was a learning curve for Stennett when he was in the field. But he needed no such excuse when he was at the plate. “He hits everything we throw him,” said the Reds’ Johnny Bench.9

With Cash entrenched at second base, Stennett seemed to be a player without a position. He put in time at shortstop and at all three spots in the outfield. The 1972 season was his fourth in pro ball, so there was a learning curve for Stennett when he was in the field. But he needed no such excuse when he was at the plate. “He hits everything we throw him,” said the Reds’ Johnny Bench.9

The Bucs captured the NL East Division again in 1972, and this time, Stennett was invited to the party. He led the club with six hits in the NLCS, but the Bucs were ousted by Cincinnati in five games.

However, the Pirates family was devastated when on December 31, 1972, Roberto Clemente lost his life. Clemente was aboard a cargo plane headed from San Juan to Nicaragua to deliver medical and food supplies to earthquake victims in Managua. Shortly after the 9:15 P.M. takeoff, the plane experienced engine problems and tried to return to San Juan International Airport, but it crashed after a series of explosions into the Atlantic Ocean about a mile-and-a-half from shore. There were no survivors.

Stennett recalled: “The only reason I was in Puerto Rico was because Roberto Clemente was supposed to play for San Juan, as he did every year, but after the World Series, he decided to take a rest. So they gave me his contract to take his place. It was my first year in the big leagues and Pittsburgh thought it would be good for me to play in Puerto Rico to gain some experience.

“That night, we went to Bob Johnson’s apartment for the New Year’s Eve party. Sometime during the night, somebody said, ‘Look over the window, there’s a ship on fire.’ We all looked and we could see flames coming from the water. We all left the party and went home, and at about four o’clock in the morning, we all got a call that woke us up to tell us that Roberto’s plane had crashed. Everybody got up and we went over to Clemente’s house. It was sad. We just couldn’t believe it.

“I’m not saying the flames we saw were Roberto’s plane, but when you put everything together, that’s what you have to think.”10

The Pirates’ 1973 season was bordered in black as a result of Clemente’s death. Virdon was relieved of his duties on September 5, even though the Pirates were in second place, just three games behind the Cardinals. But their record was 67-69 at the time and Murtaugh came down once again from the front office to manage the club. Stennett belted a career-high 10 home runs. But his batting average dropped to a career-low .242. Once again he was in no-man’s land as far as an everyday position was concerned. Virdon shuffled Stennett, Jackie Hernández, and Gene Alley at shortstop until Dal Maxvill was acquired from Oakland in early July to solidify the position. “I wasn’t myself,” Stennett said of his 1973 batting woes. “Maybe I could blame it on not playing regularly, but I was at fault, too. I got into bad habits. I swung at bad pitches and never stopped.”11 His defense improved; he made only nine errors in 77 starts at the keystone spot. His fielding percentage was .981.

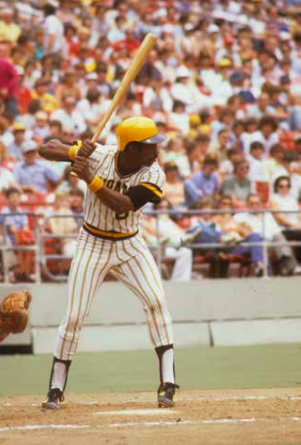

On October 18, 1973, Cash was dealt to Philadelphia for pitcher Ken Brett. The Pirates were looking for a quality starting pitcher, and felt that Cash would bring more quality their way. They also felt that Stennett was a better long-range option at second base, as he demonstrated more range than Cash. “It’s a good feeling,” said Stennett. “Just going to the ballpark every day and expecting to be in the lineup is something that is bound to help me.”12 He was correct in his assumption, as his batting average rebounded to a more Stennett-like .291 in 1974. A snowmobile accident in February 1975 hindered Stennett at the start of the ’75 season. But he finished strong, batting .367 in August and .330 in September, and batted .286 for the year. Stennett, who batted mostly leadoff in the Pirates batting order, drove in a career-high 62 runs in 1975.

Stennett was playing at a high level, in both the field and at bat for the Pirates. Noted for his hustle and grind-it-out style of play, he was a favorite in the hard-working city of Pittsburgh. “His achievements have gone unnoticed by many people,” said Pirates general manager Joe Brown. “There hasn’t been a player in baseball, not even Pete Rose, who has hustled more than Stennett this year.”13 Rennie’s glove work also was coming around. He put together a streak of 47 errorless games while playing second base in 1974. “I don’t worry about errors,” said Stennett. “I play as hard as I can and if I make an error, I make an error. There is nothing I can do about it.”14

Murtaugh was back as the full-time field manager, and the Bucs won the division title in 1974 and 1975. However, they were knocked out in the NLCS both years. Stennett’s performance during those two seasons allowed the Pirates to trade one of their prized prospects, Willie Randolph. The Pirates packaged Randolph with Ken Brett and fellow pitcher Dock Ellis and sent them to the New York Yankees for pitcher Doc Medich on December 11, 1975.

The Pirates finished second to Philadelphia in 1976. After the season the Pittsburgh family suffered another major loss, when Murtaugh, who had retired after the season, suffered a stroke and died on December 2.

Under new manager Chuck Tanner, Stennett was enjoying his best offensive year in the majors in 1977. He was batting .336 and batting sixth in the lineup, which was more to his liking. “I am a .300 hitter,” said Stennett. “I’ll always be aggressive at the plate. That’s my style. Maybe I’m not flashy. Mainly, I swing, and I’ve been getting an awful lot of hits on first pitches.”15 One part of his game was sliding. Stennett had the habit of jumping before sliding, and bruised his right shoulder while sliding into second base. “I had better learn to slide or I am going to break something some day,” he said.16

Stennett’s words were prophetic when on August 21, 1977, anticipating a force play that never occurred; he fractured a bone in his right fibula and dislocated his right ankle sliding into second base against the Giants. He was lost for the year. Phil Garner was moved from third base to second and Dale Berra was called up from Triple-A Columbus to man the hot corner. It was a big blow to the team, which was trailing the Phillies by 6½ games at the time. The Pirates had already lost Willie Stargell on July 8, when he attempted to break up a fight during a game with the Phillies and got a pinched nerve in his left elbow for his trouble. Stargell was waiting for surgery and was out for the season. Stennett was 12 at-bats shy of qualifying for the batting championship. Teammate Dave Parker won the honors with a .338 batting average.

Stennett was back to being a utility infielder in 1978. Because of his injuries, restrictions were placed on the games he would be allowed to play. He would not play both games of a doubleheader, and he would sit if the field was slick, or judged too dangerous to let him play. A bone spur developed over his right ankle, and Stennett was limited to 79 starts at second base and six at third. For the third straight season, the Pirates finished in second place to the Phillies.

The 1979 Pirates won their sixth division title, clearly making Pittsburgh the dominant team of the 1970s. The theme “We Are Family” spread through the Steel City, as they were led by co-league MVP Willie “Pops” Stargell. In retrospect, it may have been best for Stennett to take the 1978 season off in order for his ankle to heal 100 percent. Unfortunately for him, his playing time at second was split with Garner, who was also playing third. That was until a trade with San Francisco brought Bill Madlock to Pittsburgh in late June. While Madlock had been playing second base with the Giants, Tanner immediately returned the two-time batting champion to third base. Garner became the full-time starter at second; while Stennett started only 17 games after the All Star break.

The Pirates swept the Reds in the NLCS, although it was hard-fought; two of the games went into extra innings. Pittsburgh then dug out of a three-games-to-one deficit in the World Series to beat the Orioles. It was the second time in the decade that the Pirates topped Baltimore in the fall classic. But for Stennett, he was merely a benchwarmer in the postseason, totaling one at-bat between both series. “Our mentality with the Pirates was that if we were 0-for-3 and we came up in the ninth inning with the winning run on base and knocked in that run, it was like having a 4-for-4 day,” he said. “We felt we couldn’t lose.”

Stennett sensed he needed a change of scenery. He entered the re-entry draft and was claimed by the limit of 14 teams. San Francisco outbid the competition, and Stennett was the proud owner of a new five-year, $3 million pact. But Stennett never could get untracked in San Francisco. At times he was replaced by Joe Strain, a journeyman infielder, which caused Stennett to seethe. Manager Dave Bristol was not the motivational type of manager “It’s very tough to play for Dave Bristol,” said Stennett. “He puts too much pressure on players. He just doesn’t communicate. He’s old-school and you can’t depend on him for any motivation.”

Many of the other veteran players shared the same sentiment as Stennett, but because of the contract he signed, he carried much of the criticism in the media. Specifically, where did Rennie come off popping off about Bristol after hitting a measly .244?

Bristol was fired after the 1980 season and was replaced by Frank Robinson. But more importantly, two-time MVP Joe Morgan was signed as a free agent. Even though Little Joe was nearly eight years older than Stennett, he was named the Giants’ starting second baseman. A good portion of the 1981 season was washed away by a players strike, forcing the leagues to play a split season. San Francisco acquired second baseman Duane Kuiper from the Cleveland Indians after the 1981 season. Kuiper, who played for Robinson when Robby piloted the Tribe, was set to be the backup to Morgan. Stennett was released on April 2, 1982.

Stennett played for Reynosa of the Mexican League in 1982. In 1983, before retiring on July 8, he played in 55 games for Wichita of the Triple-A American Association, a Montreal Expos affiliate managed by Felipe Alou. He moved his family (Gail, his wife, and their two children, Renee and Stevie) to Florida. There he owned a carpet-cleaning business with a friend. The Stennett clan moved to Boca Raton, where he joined Davimos Sports Management in 1986. Sanguillen was a partner in the firm that counseled ballplayers, mostly Latins, on life outside the foul lines.

At 38, Stennett wanted to give baseball one more chance and he signed with the Pirates in 1989. However, he was cut at the end of the spring training. For his career, Stennett batted .274, with 41 home runs, 1,239 hits, and 432 RBIs. His career fielding percentage at second base was .978.

As of 2016 Stennett resided in Boca Raton. He kept in shape by playing tennis and enjoyed his three grandchildren. He has participated in Pirates Fantasy Camp, but also coached baseball back in his native Panama on the professional level.

Last revised: August 8, 2016

This biography appears in “When Pops Led the Family: The 1979 Pitttsburgh Pirates” (SABR, 2016), edited by Bill Nowlin and Gregory H. Wolf.

Notes

1 Phil Pepe, Talkin’ Baseball: An Oral History of Baseball in the 1970s (New York: Ballantine Publishing Group, 1998), 190.

2 Pepe, 191.

3 Dave Anderson, “7 for 7-Twice in a Century of Baseball,” New York Times, September 20, 1975.

4 Charley Feeney, “Rookie Stennett Plugs Hole at Keystone,” The Sporting News September 18, 1971: 3.

5 Ibid.

6 A.L. Hardman, “Conversions Rimp and Rennie Are Key to Charlies’ Success,” The Sporting News, June 26, 1971: 43.

7 Ibid.

8 George Skornickel, “Characters with Character: Pittsburgh’s All Black Lineup,” Baseball Research Journal, Fall 2011.

9 Charley Feeney, “Bucs’ Stennett Earns Reprieve With Hot Bat,” The Sporting News, May 27, 1972: 13.

10 Pepe, 93-94.

11 Charley Feeney, “Bat Skid Could Give Stennett a Boost,” The Sporting News, February 2, 1974: 32.

12 Ibid.

13 Charley Feeney, “Pressure Brings Out Star in Stennett, Rooker,” The Sporting News, “October 12, 1974: 3.

14 Ibid.

15 Charley Feeney, “Steady Stennett – Pirate Keystone Jewel,” The Sporting News, July 2, 1977: 13.

16 Ibid.

Full Name

Renaldo Antonio Stennett Porte

Born

April 5, 1951 at Colon, Colon (Panama)

Died

May 18, 2021 at Coconut Creek, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.