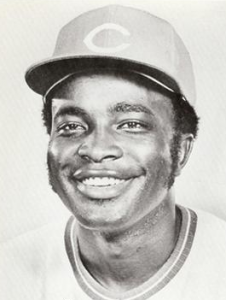

Joe Morgan

Hitting for average and power and stealing bases with aplomb, the diminutive infielder was the star of the Castlemont High School baseball team in Oakland, California. Major-league scouts were well aware of the quality of play in the East Bay. Among alumni of Oakland schools were such recent luminaries as Frank Robinson, Vada Pinson, and Curt Flood. Scouts came to Castlemont games not to see a pint-sized infielder, but to view the pitching of Rudy May, who eventually signed with the Minnesota Twins for an $8,000 bonus. Of the infielder they felt he was a good little player, with an emphasis on the second of the two adjectives. No one offered him a signing bonus.

Hitting for average and power and stealing bases with aplomb, the diminutive infielder was the star of the Castlemont High School baseball team in Oakland, California. Major-league scouts were well aware of the quality of play in the East Bay. Among alumni of Oakland schools were such recent luminaries as Frank Robinson, Vada Pinson, and Curt Flood. Scouts came to Castlemont games not to see a pint-sized infielder, but to view the pitching of Rudy May, who eventually signed with the Minnesota Twins for an $8,000 bonus. Of the infielder they felt he was a good little player, with an emphasis on the second of the two adjectives. No one offered him a signing bonus.

Who can blame them? At 5-feet-7 and 140 pounds, he did not seem a likely prospect for professional baseball. Who could have guessed that Joe Morgan would go on to become a two-time Most Valuable Player in the National League, a member of the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, and almost universal recognition as one of the greatest second basemen in the history of major-league baseball?

Joe Leonard Morgan was born September 19, 1943, in Bonham, Texas, the seat of Fannin County in the Red River Valley, not far from the Oklahoma state line. The oldest of six children born to Ollie and Leonard Morgan, Joe moved with his family to Oakland when he was 5. There his father and several other relatives secured employment with the Pacific Tire and Rubber Company. As a child Joe enjoyed playing informal games of football, basketball, and baseball, often without using a regulation ball or following the usual rules of the game. His first experience on an organized team came at the age of 13 when he won a spot on a team in the local Babe Ruth League. For each of the three years he played Babe Ruth baseball, Morgan made the league’s all-star team.

In high school Joe ran track and played basketball, but baseball was his best sport. When his team won the championship of the Oakland Athletic League, his friend Rudy May left to play professional baseball, but Joe’s hopes for a similar career were dashed. He was not even offered a baseball scholarship to a four-year college. Instead, in 1961 he enrolled in Oakland City College, a two-year school, where he majored in business and played on the baseball team. The team’s second baseman, Joe was its leading hitter and base stealer, and one of the best players in its league. At last he attracted the attention of the bird dogs. The former major leaguer Cookie Lavagetto tried unsuccessfully to get the New York Mets to sign Morgan. The youngster heard that the Yankees were interested, but nothing came of that either. Finally, on November 1, 1962, Bill Wight, a scout for the Houston Colt .45s, signed the 19-year-old for $500 a month and a $3,000 signing bonus.

After a stint at the Colt .45s’ instructional camp in Moultrie, Georgia, Morgan was assigned to the Modesto Colts of the Class A California League for the start of the 1963 season. After playing in 45 games for Modesto, he was transferred to the Durham Bulls of the Carolina League. In Durham Morgan had his first real exposure to racism. (The players had been shielded from the public in Moultrie.) He was the only black player on the team, and his arrival had been anticipated with some nervousness. Manager Billy Goodman tried to put Joe at ease by telling him he would not play in the first game, so he should just relax on the bench. Nevertheless, Joe could not help hearing hateful words coming from the stands during warm-ups. By the ninth inning, Morgan was more at ease and he was ready when Goodman called on him to pinch-hit. The Bulls were down by one run with one runner on base. In his first at-bat in Durham, Morgan hit a game-winning home run. The complaints about “niggers” were drowned out by cheers. Morgan credited Goodman with having the sensibility to put him into the game at the right time.

Shortly after his Durham debut, Morgan had another rude awakening. In Winston-Salem he was not allowed to stay in the same motel as his white teammates; he saw signs designating segregated water fountains and segregated bathrooms; and, worst of all, he saw a section of the right-field stands at the ballpark fenced off like a cage for black fans. He decided to quit, but with Goodman’s encouragement he stuck it out. Years later he wrote: “It would be nice to say that I changed my mind because of the example of earlier black players who had it tougher, like Jackie Robinson. … But my decision came from my own sense of shame and embarrassment. When I thought of facing my father and telling him that I had quit — I simply could not go ahead.”1

Goodman not only helped Morgan feel accepted by the Bulls, but he also gave him a valuable tip about hitting, suggesting that he not swing at the first pitch, but take pitches to see what kind of stuff the opposing pitcher had. Morgan took this advice to heart and had an outstanding year in Durham, hitting .332 and compiling a .528 slugging percentage. Houston changed its plans for him, bringing him to the majors sooner than it had anticipated.

When the major-league rosters were expanded in September, Morgan was promoted to the big team. On September 21, 1963, he made his major-league debut just two days after his 20th birthday. Pinch hitting in the third inning against Philadelphia starter Dallas Green, Morgan popped out to the second baseman. The next evening, he was brought in as a pinch-runner in the eighth inning against the Phillies and remained in the game. Houston had tied the game in the bottom of the ninth when Morgan came up with runners on second and third and two outs. With the count 2 and 0, Philadelphia relief pitcher Johnny Klippstein came inside with a fastball. Morgan grounded a base hit to right, driving in the winning run from third base.

Morgan spent the 1964 season with the San Antonio Bullets of the Double-A Texas League and had a fine season, hitting .323, driving in 90 runs, and stealing 47 bases. He was named the Most Valuable Player in the Texas League and earned another late-season promotion to the majors. This time he was to stay for 22 years.

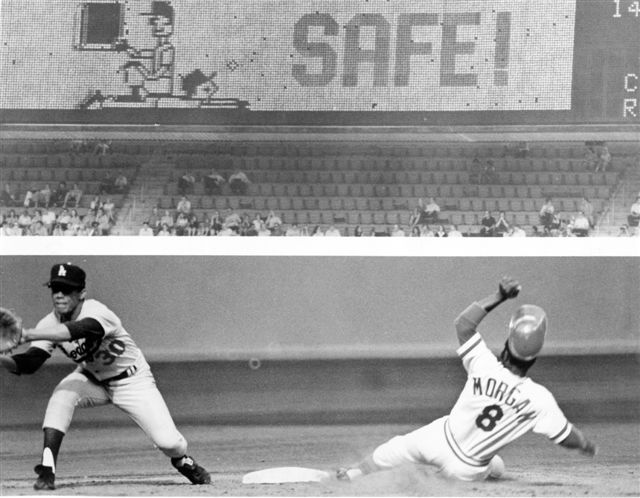

From 1965 through 1971 Morgan was Houston’s regular second baseman (except for 1968 when he was sidelined for all but ten games of the season by a torn mediate ligament in his left knee). He was a very good one, the best in the league some years, though not at the level he later attained. Early in his time at Houston, Morgan was keeping his back elbow too low when trying to hit. His teammate Nellie Fox suggested that he flap his left elbow like a chicken to keep it up. Morgan took the advice, and his flapping arm became his trademark for the rest of his career. In 1965 he finished second to Jim Lefebvre of the Dodgers in voting for the National League Rookie of the Year. In 1966 and 1970 he made the NL All-Star team. Morgan and Astros’ teammate Sonny Jackson earned some fame when they appeared together on the June 6, 1966 cover of Sports Illustrated. In his six full seasons with Houston, he ranked among the league’s top five in stolen bases four times and in bases on balls all six years. He ranked second in on-base percentage in 1966. He was a fine player.

On April 3, 1967, Morgan married Gloria Stewart, who had been his girlfriend back in his high-school days. They established a home in Houston, and Joe became involved in community affairs. He hoped to spend his entire career there. In 1971 he incurred the displeasure of manager Harry “The Hat” Walker and was placed on the trading block. Joe believed that southern-bred Walker was a racist.2 Walker claimed that Morgan was selfish, moody, and a troublemaker. On November 29, 1971, Morgan was traded along with outfielders Ed Armbrister and Cesar Geronimo, pitcher Jack Billingham, and infielder Denis Menke to the Cincinnati Reds for second baseman Tommy Helms, first baseman Lee May, and utilityman Jimmy Stewart. Morgan was very unhappy at being traded. Gloria was pregnant with their second daughter, Angela. Their first daughter, Lisa, was not quite 3 years old. Gloria did not accompany Joe to Cincinnati, but she did join him there later. For his baseball career, however, the trade could not have worked out better for Joe. He immediately became one of the biggest stars in the game. In his very first year with the Reds Morgan led the National League in runs scored, bases on balls, and on-base percentage.

Cincinnati fans were not pleased about the trade. Helms and especially the slugging May were among the most popular players on the Reds. “I just want you to know that whatever happened in Houston is over,” manager Sparky Anderson told his new player. “You get a fresh start here.”3 Sparky assigned Morgan the locker right next to Pete Rose, hoping that some of Charlie Hustle’s spirit might rub off on the newcomer. Morgan quickly exceeded his manager’s expectations. Soon Sparky was saying, “That little man can do everything.”4 He later said that Morgan was the “smartest player I ever coached.”5

When Morgan joined the Reds, they were not one big, happy family. Pete Rose, playing in his hometown, had long been the favorite of Cincinnati fans. He resented the attention given to neophyte Johnny Bench, the great catcher from Oklahoma. According to Morgan, there were four leaders on the team. He and Rose on one side, Bench and Perez on the other. Morgan wrote that another player came up to him one day and said: “You can’t be Pete’s friend and John’s friend. … On this ball club you can be friends with one but not with both.”6

Morgan initially thought that Dave Concepcion, the shortstop with whom he had to partner on double plays, was not a worthy teammate. Joe thought the shortstop was not only an inferior player, but that he was lackadaisical and sometimes lacked concentration on the field. Morgan later changed his mind about Concepcion and praised him highly in his autobiography.7 However, he never granted him the star status that the shortstop craved. One reserve player on the team complained that the stars got preferential treatment. Manager Anderson replied: “You’re damn right they do and don’t expect me to treat you the same. When you contribute to the team what they do, then you’ll get the same kind of consideration.”8 Under Sparky’s guidance the team pulled itself together, won the National League West and defeated the Pittsburgh Pirates three games to two during a dramatic NLCS, but lost the 1972 World Series to the Oakland Athletics in seven games. Morgan hit .263 with two home runs in the NLCS, and only batted .125 in the World Series.

Morgan initially thought that Dave Concepcion, the shortstop with whom he had to partner on double plays, was not a worthy teammate. Joe thought the shortstop was not only an inferior player, but that he was lackadaisical and sometimes lacked concentration on the field. Morgan later changed his mind about Concepcion and praised him highly in his autobiography.7 However, he never granted him the star status that the shortstop craved. One reserve player on the team complained that the stars got preferential treatment. Manager Anderson replied: “You’re damn right they do and don’t expect me to treat you the same. When you contribute to the team what they do, then you’ll get the same kind of consideration.”8 Under Sparky’s guidance the team pulled itself together, won the National League West and defeated the Pittsburgh Pirates three games to two during a dramatic NLCS, but lost the 1972 World Series to the Oakland Athletics in seven games. Morgan hit .263 with two home runs in the NLCS, and only batted .125 in the World Series.

In 1973 the Reds won the most regular-season games of any team in the major leagues, but they lost the NLCS in five games to the New York Mets, who had won the East with the lowest winning percentage (.509) ever for a pennant winner. Morgan did not distinguish himself in the postseason, collecting only two hits in 20 times at bat. In 1974 the Reds finished second to the Los Angeles Dodgers in the NL West. Morgan again led the league in on-base percentage and won his first Gold Glove, his third consecutive outstanding season with the Reds. But Cincinnati fans were disgruntled and Sparky Anderson’s job was said to be in jeopardy.

The Reds got off to a poor start in 1975. For much of April and part of May they were at .500 or had a losing record, although Morgan was going great. By April 22, he had walked 15 times in the first 15 games and was hitting over .400. Of his starting teammates, only Rose was hitting as high as .300. Going into an afternoon game at Riverfront Stadium against the San Francisco Giants on the 22nd, the Reds were in fifth place, with a 7-8 record. With the score tied, 4-4, in the bottom of the ninth, Morgan stroked a one-out double, and then Bench was walked intentionally. Still slumping, Perez struck out. With Cesar Geronimo at the plate and two outs, San Francisco Giants’ relief pitcher Charlie Williams threw a pitch in the dirt that got by catcher Marc Hill for a wild pitch. Morgan took off for third but slowed before reaching the bag. Hill tried to throw Morgan out, but his hurried peg went past the third baseman and down the left field line. Joe raced home with the winning run. After the game he rubbed salt in the Giants’ wounds by telling reporters: “I could have made third easily, but I deliberately held back. … I was hoping Hill would do just what he did.”9 The Giants were furious. “If Joe Morgan keeps up his current pace,” Anderson said, “He’ll be dead in another month.”10 The Giants were not the only players who disliked Morgan. Many baseball people thought he was arrogant.

By June 7, the Reds were in first place to stay. Anderson’s risky experiment of moving Rose from left field to third base was paying dividends. The switch enabled George Foster to move to left field, opening up right field for young Ken Griffey. Both Foster and Griffey hit .300 or better that season, but they did not receive much support from Morgan. “George and I both kept waiting for him to take us under his wing, but it didn’t happen,” Griffey said.11 In center field Geronimo was leading the league in putouts. As summer turned into autumn, the Reds were running away with the NL West. The Big Red Machine cruised to 108 victories, the most by any National League club since the Pirates of 1909. After being a viable candidate for three years, Morgan easily won the Most Valuable Player Award. He hit .327, led the league with an on-base percentage of .466, drew 132 bases on balls, stole 67 bases and won his third straight Gold Glove. “I have never seen anyone, and I mean anyone, play better than Joe has played this year,” gushed Anderson.12

The Reds swept Pittsburgh in three straight to take the NLCS. The Boston Red Sox won the American League title, setting the stage for one of the greatest World Series in the history of baseball. Morgan hit just 7-for-27 in the Series, and was victimized by a spectacular catch by Dwight Evans in the historic Game Six, but he had two crucial hits: his tenth-inning game-ending single in Game Three, and his game-winning single in the top of the ninth in Game Seven as the Reds won the dramatic Series.

Heading into 1976, most observers thought the Reds and their second baseman were each second to none. The April 12, 1976 issue of Sports Illustrated had Morgan on the cover proclaiming Joe as “The Complete Player”. To the surprise of no one, the Reds again rolled to the National League pennant. Their 102 victories were ten more than the Dodgers could win in the West. In the postseason, the Reds swept Philadelphia in three games during the NLCS and then swept the New York Yankees in four games during the World Series. They became the first National League team since the 1921 and 1922 New York Giants to win two consecutive World Series. (No National League club has done it since.) They were the only club besides the 1922 Giants and the 1963 Dodgers to sweep the Yankees in a World Series.

Morgan again won the MVP award, as he remarkably improved upon his spectacular 1975 season. He hit .320, led the league in on-base percentage and slugging percentage, hit a career-best 27 home runs, scored 113 runs, batted in 111, walked 114 times, and stole 60 bases. For his fielding, he won his fourth consecutive Gold Glove. It was truly one of the best seasons any player has ever had.

The Reds dealt Perez after the 1976 season, and the team slowly disintegrated after that. Morgan had a fine year in 1977, .288 with 22 home runs and 117 walks, though a bit down from his remarkable 1972-76 stretch. The team finished a distant second to the Dodgers, which they would also do in 1978. Morgan hit just .236 in 1978 and .250 the next year, with his other numbers down as well. After the 1978 season Rose left as a free agent and Anderson was fired. The Reds team that won the 1979 NL West division bore only a passing resemblance to the Big Red Machine, and the Pirates quickly dispatched them in three games during the NLCS. After the season Morgan, now 36 years old, declared for free agency and signed with the Houston Astros, his old team.

After leaving Cincinnati, Morgan played for five more years in the major leagues – one season for Houston, two for the Giants, and one each for the Phillies and the Oakland Athletics. He was still a very effective player, if no longer quite a star. In 1982, Morgan won the NL Comeback Player of the Year and the Silver Slugger Award for second basemen. In the 1983 World Series, Joe hit two home runs during the Phillies’ five-game series loss to Baltimore. He played his last game on September 30, 1984, at the age of 41. He went out in style, hitting a first inning double off Kansas City’s Mark Gubicza in his last time at bat. Tony Phillips was sent in to pinch run for Morgan, and Joe left the field to a large ovation from the Oakland fans.

Following his retirement as a player, Morgan pursued interests in business, broadcasting, and philanthropy. For a time he ran three Wendy’s franchises in the Oakland area, then he became a distributor for Coors Beer in Northern California. Fulfilling a promise he had made to his mother 27 years earlier, he finished college, earning his B.A. degree from California State College-Hayward in 1990.

Morgan started his broadcasting career in 1985 for the Cincinnati Reds. Later he broadcast games for San Francisco and Oakland. In 1988 and 1989 he announced for ABC and from 1994 to 2000 he was with NBC. His best known stint as an announcer was with ESPN, where he teamed with Jon Miller for 21 years on “Sunday Night Baseball” telecasts. Morgan’s keen intelligence and vast experience enabled him to be an insightful analyst. Like all announcers, he had his detractors, as some felt he was self-righteous and uninterested in new ways of studying the game.

Morgan’s ESPN contract was not renewed after the 2010 season. He accepted a position with the Cincinnati Reds as “special advisor to baseball operations.” His duties were primarily in the areas of community outreach and diversity. In 2011 he became host of a syndicated weekly radio program on Sports USA, called “The Joe Morgan Show.”

In 2000 Morgan became vice chairman of the Board of Directors of the National Baseball Hall of Fame. He also joined the boards of a number of other charitable and civic organizations. Among his chief interests was Adventures in Movement, which uses music to help handicapped children experience movement in an enjoyable way. (Morgan is an ardent jazz fan.) He also joined the board of directors of the Baseball Assistance Team (BAT), dedicated to helping former major-league, minor-league, and Negro League players through financial and medical hardships.

On March 15, 1988, while in the Los Angeles International Airport, waiting to make connections for a flight to Phoenix for a charity event, Morgan was detained by two undercover police officers who accused him of being a drug courier. One of the officers pinned Morgan’s arms behind him, kneed him in the back, and knocked him to the ground. “Over the next hours, the nightmare deepened, and it was all because I was just another black man. No longer a celebrity, as anonymous as any other black man, I was exposed to whatever fury was going to be meted out,” he wrote in his autobiography.13 After Morgan was taken to the police station, he was able to prove his identity and was released, but was not allowed to file a complaint. He filed a suit against the LAPD. In 1993 the Los Angeles City Council settled the suit for $796,000.

In the late 1980s Joe and Gloria drifted apart and divorced. In 1990 he married Theresa Behymer. As Theresa was white, it took some time for both sets of parents to accept the marriage. On February 9, 1991, twin daughters, Kelly Ann and Ashley Lauren, were born in San Francisco. Both daughters grew up to be college athletes. Kelly played soccer at the University of Southern California, and Ashley became a national champion gymnast at Stanford.

In 1990, the first year of his eligibility, Morgan was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame, the highest honor that can come to a baseball player. The good little infielder had proved that he belonged among the game’s elite.

Morgan died at the age of 77 on October 11, 2020, at his home in Danville, California.

Last revised: April 16, 2021 (zp)

An earlier version of this biography is included in SABR’s “The Great Eight: The 1975 Cincinnati Reds” (University of Nebraska Press, 2014), edited by Mark Armour.

Notes

1 Joe Morgan and David Falkner, Joe Morgan: A Life in Baseball. ( New York: W.W.Norton & Co., 1993), 52-53.

2 Walker, along with his brother Dixie, had been among the leaders of the attempted boycott of Jackie Robinson back in 1947.

3 Joe Posnanski, The Machine (New York: William Morrow, 2009), 42.

4 Posnanski, 42.

5 Posnanski, 43.

6 Morgan and Falkner, 142.

7 Morgan and Falkner, 156-158

8 Morgan and Falkner, 162.

9 Posnanski, 84.

10 Posnanski, 84.

11 Posnanski, 132.

12 Posnanski, 190.

13 Morgan and Falkner, 98-99.

Full Name

Joe Leonard Morgan

Born

September 19, 1943 at Bonham, TX (US)

Died

October 11, 2020 at Danville, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.