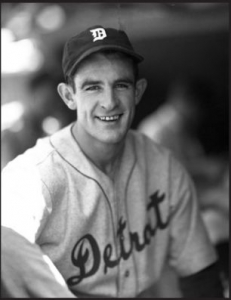

Elden Auker

Over a major-league career that lasted 10 seasons, Elden Auker played for Hall of Fame managers Bucky Harris, Mickey Cochrane (who called him “Mule Ears”), and Joe Cronin (who severely limited Auker’s effectiveness by calling, from his shortstop position, each pitch Auker was to throw). Auker was a teammate of Hall of Famers Hank Greenberg, Charlie Gehringer, Goose Goslin, and Al Simmons on the Tigers; Jimmie Foxx, Lefty Grove, Bobby Doerr, and Ted Williams on the Red Sox; and Rick Ferrell on the St. Louis Browns.

Over a major-league career that lasted 10 seasons, Elden Auker played for Hall of Fame managers Bucky Harris, Mickey Cochrane (who called him “Mule Ears”), and Joe Cronin (who severely limited Auker’s effectiveness by calling, from his shortstop position, each pitch Auker was to throw). Auker was a teammate of Hall of Famers Hank Greenberg, Charlie Gehringer, Goose Goslin, and Al Simmons on the Tigers; Jimmie Foxx, Lefty Grove, Bobby Doerr, and Ted Williams on the Red Sox; and Rick Ferrell on the St. Louis Browns.

Born in Norcatur (population approximately 500) in rural Kansas on September 21, 1910, Elden was an only child. Surrounded by farms sprawled over the prairie, downtown Norcatur was just two blocks long. The town’s only saloon shut down during Prohibition and never reopened. By the time he was six weeks old everyone in town knew Elden. His father, Fred, was the town’s only postman, and his mother took him along on his father’s route and introduced Elden to all the postal patrons. Initially Fred delivered the mail on horseback, but before Elden was born he was using a motorcycle in the more temperate months and a horse-drawn wagon in the harsh winter. The family income was supplemented by marketing milk and eggs. Elden’s mother was in charge of this effort. His first job was to deliver these products in his red express wagon. At an early age Elden had instilled in him by his parents a respect for the value of money.

Norcatur High School didn’t have a baseball team, so beginning at age 15, Auker played on the town team with the men. After graduating from high school in 1928, he attended Kansas Agricultural and Mechanical College (today Kansas State) in Manhattan, Kansas. Charlie Corseau, who recruited him, was the varsity basketball and baseball coach there, and arranged part-time jobs for Elden so he could pay his way. Auker’s goal was to become a medical doctor and he took the appropriate courses in anatomy, physiology, chemistry, psychology, etc., to prepare for that profession.

While in college, Auker played varsity football (quarterback), baseball (pitcher), and basketball (guard and team captain). He was voted All Big Six in all three sports. This resulted in a college nickname: Big Six. But in his autobiography, Auker wrote that no one in major-league baseball ever called him that.

Football was his favorite sport. Ironically, in his first college football game, Auker permanently injured his right shoulder. This prevented him from ever throwing overhand. To compensate for the shoulder separation, he learned to pitch with a slightly underhand motion.

Auker always took on extra jobs to earn money, which was in short supply in the 1930s. In the summer of 1931 he pitched for pay on a town team, the Manhattan Travelers, and faced Satchel Paige, who was pitching for the legendary Kansas City Monarchs. Auker beat Paige, 2-1, the Monarchs’ only run coming on a home run by catcher T.J. Young. This loss broke the Monarchs’ 33-game winning streak. Later that summer Auker played for another town team in Oxford, Nebraska, but under the name Eddie Leroy to preserve his college eligibility. Once more his team faced Kansas City, but this time a pitcher named Andy Cooper was on the mound for the Monarchs. Auker threw a shutout, winning 1-0. Auker thought Cooper had a sharper curveball than Paige, and was at least as good a pitcher as Paige, if not better.

After graduation in 1932, Auker was scouted by football great Bronko Nagurski and turned down an offer of $6,000 from the Chicago Bears to play pro football. Instead he signed with the Detroit Tigers for $450. He decided to play baseball because he would start getting his paychecks instead of waiting until the fall, when the football season started. Auker’s intention was to play pro baseball as a means of earning tuition money for medical school. But he made such good money at baseball that he couldn’t afford to give it up. Besides, the Depression was in full force and both jobs and money were scarce.

At one of his first minor-league stops, Decatur of the Three-I League in 1932, Auker’s manager was Bob Coleman, who had caught perhaps the most famous submarine pitcher to ever work in the majors, Carl Mays. Coleman suggested that Auker modify his slightly underhand throwing motion even more, and throw directly underhand. Before the 1933 season ended, Auker, who was 16-10 with Beaumont of the Texas League, was called up to “The Show” by the Detroit Tigers. He started six games and relieved in nine others, going 3-3 overall. He pitched a total of 55 innings.

Also in 1933, Elden married Mildred Purcell, a college classmate. In their senior year Elden was voted “Joe College,” and Mildred “Betty Coed.” Although they knew each other in college they didn’t date until after graduation. Their only child, a son, James, was born in 1939. Their marriage was better than any Hollywood love story and Elden and Mildred were devoted to each other for their entire lives.

After the 1933 season, Mickey Cochrane replaced Bucky Harris as the Tigers’ skipper. Cochrane was a dynamic playing manager who infused a winning spirit in the club by constantly exhorting his players to do better. The talent was there, and the club responded. The Tigers had an outstanding pitching staff, led by Lynwood “Schoolboy” Rowe and Tommy Bridges (24-8 and 22-11, respectively), and ably supported by Auker’s fine 15-7 season, along with another 15 wins from Fred (Firpo) Marberry. The Bengals coasted to victory with a record of 101-53, seven games ahead of the aging Yankees.

The ’34 Tigers were a powerhouse team and boasted an infield that combined to drive in an astonishing total of 462 runs. Four members of the team would be elected to the Hall of Fame: Cochrane, Charlie Gehringer, Goose Goslin, and Hank Greenberg.

In the National League, the St. Louis Cardinals won their fourth pennant since 1926 —behind four different managers. The latest version of the Cards, known as the Gas House Gang, was led by another playing manager, Frankie Frisch. The Cardinals’ roster included five players destined for the Hall of Fame —Dizzy Dean, Leo Durocher, Frisch, Joe Medwick, and Dazzy Vance. They had a 95-58 record and the ’34 season would be their finest moment, as the fabled Gas House Gang never won another pennant.

The 1934 Series opened in Detroit, and the Cardinals took the opener, 8-3, with Dizzy Dean besting Alvin “General” Crowder. In the second game Schoolboy Rowe went all the way as the Tigers scored a run in the bottom of the ninth to pull out a 3-2 victory. Bill Walker took the loss for the Cards.

The Series shifted to St. Louis, where the Cardinals won the third game, 4-1. Paul Dean beat Tommy Bridges, who was knocked out in the fifth inning after facing three hitters without retiring anyone.

The Cardinals now led two games to one and the Tigers needed a win. Auker was matched against Tex Carleton in the fourth game. Elden pitched a complete game as Bill Walker again took the loss in relief. Auker gave up 10 hits and three earned runs in a 10-4 Tigers victory.

At the end of six games the Series was dead even. Auker started the crucial Game Seven at home, opposing Dizzy Dean. Auker pitched well enough for the first two innings, allowing three hits, but Dizzy Dean kept the Tigers from scoring, too. After Auker got the first out in the top of the third, Dean doubled to left. Pepper Martin then beat out a slow roller to first, giving the Cardinals runners on first and third. Martin promptly stole second, and outfielder Jack Rothrock walked, loading the bases. The next batter was the switch-hitting Frisch. He fouled off four pitches and then doubled to right field, clearing the bases.

Cochrane removed Auker in favor of Rowe, who got Medwick to ground out to short, with Frisch taking third. St. Louis kept hitting, though, and by the time the inning was over, the Cardinals had scored seven runs. It was quite a game, and Tigers fans displayed their frustration after Joe Medwick and Tigers third baseman Marvin Owen tangled in a fight on the field. The crowd pelted Medwick with bottles, food, and all sorts of trash as soon as he took his position in left field. The mob was in such an uproar that the game had to be halted. Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis ordered that Medwick be removed from the game “for his own safety.” The final score was 11-0, bringing the championship home to St. Louis.

Auker got some measure of revenge by winning the first major-league baseball players’ winter golf tournament in Lakeland, Florida, in January 1935, defeating Dizzy Dean and Babe Ruth, among others.

The Tigers picked up in 1935 right where they left off in ’34, winning the AL pennant with a record of 93-58. The team was largely unchanged, but General Crowder, at 16-10, improved greatly over his 1934 season (he was a combined 9-11 with Washington and Detroit). Auker was also better, at 18-7, and led the league with a winning percentage of .720. It was his best season ever. In the World Series the Tigers faced the Chicago Cubs, who had compiled a record of 100-54 under Charlie Grimm.

With the Series tied at one game each, Auker started Game Three in Chicago against Bill Lee. Auker gave up a solo home run to Frank Demaree in the second, in addition to a scratch run. The Cubs squeaked out another run in the fifth, and the Tigers got on board in the sixth on a Pete Fox triple that scored Goslin. The top of the seventh started with Marvin Owen flying out to right field. When utility infielder Flea Clifton walked, manager Cochrane saw a chance to ignite a rally and sent Gee Walker up to bat for Auker. Walker promptly hit into a double play, ending the rally and the inning. But in the eighth, the Tigers scored four runs, getting Auker off the hook. They won the game by a score of 6-5. It was Auker’s only appearance in the 1935 Series. The joy in Detroit knew no bounds when the Tigers went on to win their first-ever world championship. But that powerhouse Detroit team was not able to win another pennant until 1940. By then Auker was no longer part of the team.

Auker’s years in Detroit were happy ones. It was a close-knit team and produced lifelong friendships. But the idyllic situation came to an abrupt end after the 1938 season, when Auker was traded, along with reserve outfielder Chet Morgan and pitcher Jack Wade, to the Boston Red Sox for third baseman Mike Higgins and pitcher Archie McKain. Detroit felt this trade was necessary because Marv Owen was in poor health and ready to retire. Over his five-plus seasons with Detroit, Auker started 136 games and completed 70 of them, compiling a record of 77 wins and 52 losses.

In Boston, according to Auker, manager-shortstop Joe Cronin called each pitch for all his pitchers except Lefty Grove. Auker didn’t learn of this until well into the season. He complained bitterly about not being allowed to pitch as he thought best, but to no avail. Auker dealt with this situation by disregarding the catcher’s signals. Cronin responded to this rebellious act by temporarily taking Auker out of the pitching rotation. Auker’s performance suffered in 1939 as he lost 10 games while winning 9. He completed only six of the 25 games he started.

On the bright side of this unhappy year, Auker became lifelong friends with Ted Williams. They truly loved each other. Years later, at events hosted by the Ted Williams Museum and Hitters Hall of Fame in Citrus Hills, Florida, Williams and Auker would discuss the fine points of hitting and pitching. Whenever they disagreed on some particular, Ted would look Elden right in the eye and bellow out, “Goddammit Elden, pitchers are dumb, dumb, dumb.” Elden didn’t take this personally, as it was Ted’s universal judgment of all pitchers.

Auker roomed with Jimmie Foxx while on the road in 1939, and came to respect and admire Double-X so much that he named his only child James Emory in his honor. Fortunately, the child was a boy.

At the end of the 1939 season, Auker told Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey he couldn’t play for Cronin and would retire if Yawkey didn’t trade him. After being assured by St. Louis Browns manager Fred Haney that Auker could call his own game, Yawkey sold the pitcher to St. Louis for $30,000.

The Browns simply didn’t compare with either the Tigers or the Red Sox. They were not contenders, and finished a dismal sixth in 1940 and 1941. Luke Sewell took over as manager in 1942 and the Brownies rose to third place, winning 82 games. Auker won 14 of those games and earned a substantial salary. World War II was now raging, and Auker felt he had to devote full time to what up until then had been his offseason job.

Auker realized that his career as a ballplayer wasn’t going to last forever. In 1938 he began to prepare himself for life after baseball. He and Mildred stayed in Detroit that winter instead of going to Florida to chase a little white ball around the golf links. A Detroit friend, Jim Jackson, offered him a job at his small firm, the Midwest Abrasive Company. Auker learned the abrasive industry from the ground up by working in all departments. The next year he moved into the sales department, and then learned how the abrasive was employed in the honing process that removed all the microscopic rough spots from the interior of 20mm and 40mm anti-aircraft gun barrels —a critical step in fabricating accurate gun barrels. By the end of 1942, Auker was a vital link in the production of defensive armaments for the Navy and he believed his country needed him more than baseball. Although offered a lucrative contract by St. Louis, he decided not to return for the 1943 season. He was 32 years old, and was fully aware that by the time the war ended he would be too old to resume his career on the diamond.

Abandoning baseball and committing himself to the war effort was a noble, patriotic decision. It was also a very expensive one, as his annual income was greatly reduced. Ultimately, Auker was rewarded; by the time he retired in 1975, he had risen to be president of what was then the industry’s second largest firm, and was very well off financially.

As Auker rose up the executive ladder, he and Mildred were obliged to relocate to Massachusetts. There, in addition to his corporate responsibilities, Auker became the vice president of the National Association of Manufacturers, and president and chairman of the board of the Associated Industries of Massachusetts, a manufacturers’ trade group. In this role he met Joseph Kennedy (father of the president), Ronald Reagan, and Barry Goldwater, played golf with Gerald Ford and Tip O’Neill, and interacted with numerous other important people.

Immediately after his retirement in 1975, Auker was hired by Dresser Industries, the parent company of the division from which he had retired, as a consultant to evaluate its Washington office. He and Mildred had just purchased a home in Vero Beach, Florida, but Auker accepted the offer and commuted by air each weekend to Florida for a year.

Auker and Mildred became full-time residents of Vero Beach when he completed the consulting agreement in 1977. In his 80s, he joined the Society for American Baseball Research in 1997 and attended every meeting of the Central Florida Chapter. Andy Seminick, a resident of Cocoa, Florida, also became a chapter member. In 1998 the chapter was renamed the Auker-Seminick (alphabetical order) Chapter in their honor. The chapter celebrated Elden’s 90th birthday in 2000 and hosted a party for him. When asked how he spent his time, he replied that he played golf two or three times a week. Naturally, someone asked him about his score. With a smile Elden softly said that it was less than his age.

Typically, a chapter meeting centered on one of the members making a presentation of their latest research findings. Then the meeting took the form of an open discussion. Both Auker and Seminick freely participated and candidly shared their baseball experiences. Elden’s tales from the diamond were enthralling, as was his entire life story. Just possibly the experience of talking about his career, and the enthusiastic reception to it, led him to write his autobiography, Sleeper Cars and Flannel Uniforms.

In his book, Auker made it quite clear that he didn’t put up with cheaters, or rule violators like Pete Rose. Although Elden was a soft-spoken and gentle man, it was evident that he was made of iron when it came to his moral code.

It was also clear that he thought current pitchers were not up to the physical standards of his day. Typically, Auker reported, the day after pitching a game he would do some easy throwing and a lot of hard running in the outfield. The following day he would throw batting practice from the mound. And Auker threw hard stuff, no creampuffs or meatballs. He worked to improve the command of his pitches, and didn’t care to be hit hard by his teammates. A teammate had to earn a solid hit, even if it was just BP. After throwing batting practice, Auker would do more hard running in the outfield. He religiously ran hard every day. He was convinced that a pitcher’s strength came from his legs. Simply doing wind sprints didn’t improve leg strength and Auker was an advocate of running as hard as possible.

The major change Auker observed in pitching technique had to do with brushing back a hitter. He said emphatically, “The plate is mine. If a batter gets into my territory I’m going to make him eat dirt.”1 Auker said he never threw to hurt a hitter, but plunking him in the ribs to back him off the plate was acceptable. In Auker’s opinion, the rule change that prevented a pitcher from doing this tipped the balance sharply in the hitter’s favor.

When Tiger Stadium was “retired” at the end of the 1999 season, Auker participated in the solemn ceremony. As the senior Tiger in attendance he stood at the head of a line of 60 Tigers players, arranged in order of seniority, anchored at the other end by the current team captain, catcher Brad Ausmus. Auker’s remarks over the public address system clearly indicated that in his heart and mind he was still a Tiger. The flag was lowered, folded, and passed from the center-field flagpole from one player to the next until it reached home plate. It was then put into storage until Opening Day of the 2000 season, when the process of passing the flag from home plate out to the center-field flagpole was repeated by the same players at the new home of the Tigers, Comerica Park. Elden’s son, James, arranged to get a copy of the video and Elden showed it at the next meeting of SABR.

Another honor came to Auker on May 27, 2000. His home town of Norcatur dedicated a park in his name. The land was donated by Jim Nelson, a boyhood buddy of Elden’s. It was a very emotional moment for Elden and Mildred, as the entire town turned out for the ceremony, highlighted by a band playing the national anthem as the flag was raised.

Elden had a long history of heart problems —he was on his third pacemaker —and on August 4, 2006, he died from heart failure. A memorial service celebrating his life was held at the First United Methodist Church of Vero Beach. It was attended by a huge throng of relatives, friends, business associates, and fellow SABR members. His son, James, and two grandsons eulogized Elden. Their tender, loving words moved the audience greatly. Immediately following the service his family hosted a reception in the Christian Life Center Fellowship Hall.

Sources

Auker, Elden, with Tom Keegan, Sleeper Cars and Flannel Uniforms (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2001).

Bucek, Jeanine, ed., The Baseball Encyclopedia. Tenth Edition (New York: Macmillan, 1996).

Cohen, Richard M., and David S. Neft, The World Series (New York: Dial Press, 1979).

Levenson, Barry, The Seventh Game (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004).

Schaefer, Robert, personal notes taken at meetings of the Auker-Seminick

SABR Chapter, 1996-2006.

Van Brimmer, Kevin, “Auker was ‘Treasure to Game, Humanity.’ ” TC Palm (Obituary), August 5, 2006.

Notes

1 Author’s conversation with Elden Auker at a SABR Regional (Central Florida) Chapter Meeting, 1997.

Full Name

Elden LeRoy Auker

Born

September 21, 1910 at Norcatur, KS (USA)

Died

August 4, 2006 at Vero Beach, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.