Joe Dunn

Joe Dunn spent parts of four decades in professional baseball and held nearly every job except umpire. He broke in with Columbia in the Sally league in 1906 and served as a player, manager, scout, owner, or general manager until the fall of 1932. He was a fiery competitor on the field and a stern, demanding manager known for his drill-sergeant-like demeanor. When World War I broke out, one of his minor-league players, Pepper Clarke, was interviewed about his impending induction and the rigors of Army discipline. Clarke said, “I think I should be able to escape all punishment after playing for the honorable Joe Dunn for two seasons. I’ll have no fear whatsoever.”

Joe Dunn spent parts of four decades in professional baseball and held nearly every job except umpire. He broke in with Columbia in the Sally league in 1906 and served as a player, manager, scout, owner, or general manager until the fall of 1932. He was a fiery competitor on the field and a stern, demanding manager known for his drill-sergeant-like demeanor. When World War I broke out, one of his minor-league players, Pepper Clarke, was interviewed about his impending induction and the rigors of Army discipline. Clarke said, “I think I should be able to escape all punishment after playing for the honorable Joe Dunn for two seasons. I’ll have no fear whatsoever.”

Joseph Edward Dunn was born on March 11, 1885, in Springfield, Ohio. His parents were Charles Patrick Dunn, a native of County Laois in Ireland, and Mary Ellen Campion. Charles emigrated to America in 1849 and settled in Urbana, Ohio, where he worked as a day laborer. He married Mary Ellen Campion in 1869 and they moved to Springfield, Ohio, where Charles worked as a molder for the Leffel Co. They had five children (three daughters and two sons), of whom Joseph was the youngest.

Growing up in Springfield, Joseph earned the nickname Bullets as a strong-armed catcher in leagues around town. In the fall of 1905 he was signed by the Atlanta Crackers of the Southern Association; the following spring his contract was transferred to the Columbia Gamecocks of the South Atlantic League, where he won the starting catcher’s job in competition with three other backstops. Joe’s defense earned him praise, especially when he threw out two would-be Brooklyn base stealers in an exhibition game. But even though he weighed just 160 pounds, he was unable to hit anywhere near his weight (.118). In the first week of May, he went 0-for-11 and “fanned nearly every time up,” according to a contemporary newspaper account. A new catcher was brought in and Dunn saw very little action until he was released in early June. He caught on with Sumter of the Class D South Carolina League but was released after a few days and joined Darlington in the same league, for whom he appeared in 46 games, mostly behind the plate but with a few games at first base. Box scores for all but four of his games show that Dunn batted .238 (35-for-147), with eight doubles, a triple, and six stolen bases. He had a .980 fielding average, with six errors. The State in Columbia named him to its league all-star squad. Two days after the season closed, Dunn joined the Roanoke Highlanders of the Class C Virginia League, where he batted.230 in 17 games. Joe returned to Springfield for the winter and most likely worked for the city water department. (In later years he found offseason employment with the post office because his brother Charles was the postmaster.)

During his playing days Dunn established a network of friends and acquaintances and tapped them to build clubs as a manager and later as an owner. In 1907, after Springfield resident Bill Donahue signed with Evansville of the Central League, Dunn used the hometown connection to get a job as a utilityman on the team. He filled in when Donahue was sent home with a case of malaria, and later for other players who were injured. He was even forced to play injured himself, but nothing was wrong with his arm. In a game in August he gunned down four Dayton runners. For the season Dunn played in 101 games and batted .245.

Dunn returned to Evansville in 1908 after a holdout that saw him return two contracts unsigned. Unlike 1907, this time he was the regular catcher. He had what was arguably his finest season as he hit .266 in 113 games and earned a call to the major leagues. After a slow start, Evansville hit a hot streak and landed in first place in mid-July. They shook off a challenge from Dayton and cruised to the pennant. Dunn’s defense earned him glowing comments in newspapers throughout the league. A report that he had been purchased by Cincinnati proved untrue, and Dunn joined the Brooklyn Superbas at the close of the Central League season. Brooklyn needed Dunn to fill in for regular catcher Bill Bergen, who had been injured in a collision and was out for the season. The Springfield Daily News reported that Dunn had a charley horse and reported in less than top condition. The leg must have bothered him, because at season’s end The Sporting News said that Dunn was giving up too many stolen bases, and “will have to improve in his throwing if he expects to keep his job.”

Dunn’s first at-bat for the Superbas was against Christy Mathewson on September 12, and he launched a double to the right-field fence that scored two runs. His next time up Dunn ripped a single. In his fourth trip to the plate “he slashed out a grounder that nearly took Herzog’s foot away,” according to the Brooklyn Eagle. The hot shot was ruled an error, though the Eagle said that nine out of ten scorers would have called it a hit. Dunn started seven of Brooklyn’s next eight games. Catcher Alex Farmer returned from injury and he and Dunn split the duries the rest of the season. Dunn played in 20 games, including both games of a doubleheader against the Cubs on September 27 when Ed Reulbach pitched two shutouts. For the season, he hit .172 and earned an invitation to spring training in 1909.

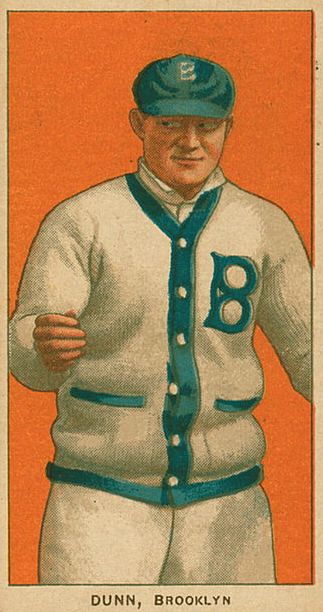

Brooklyn kept three catchers in 1909. Bergen came back from his injury and caught 112 games despite hitting a dismal .139. Doc Marshall was brought in and played in 50 games. This meant there was little opportunity for Dunn. He saw action in 10 games and batted only 27 times. In midseason he left the team in Pittsburgh briefly to act as best man at his brother’s wedding in Springfield. Dunn made his last major-league appearance on September 26 at St. Louis. He went hitless but started a 2-5 double play in the 1-0 win. Though he played little in 1909, he still was included in the memorable T-206 tobacco card set.

During the winter Joe was interviewed by the Springfield Daily News and said he hoped to see more action the next season. He got his wish, but it wasn’t on the major-league level. It’s unclear how Dunn left the Superbas – trade or release – but he was signed by Mobile of the Southern Association and started a three-year stint with the Sea Gulls. Dunn appeared in 110 games and hit .162 for the sixth-place Gulls. The 1911 version of the team was even worse, finishing in seventh place. Dunn missed a two-week stretch when he was injured fielding a bunt. He appeared in 95 games and hit .169.

In 1912 the Gulls brought in veteran minor-league manager Mike “Duke” Finn. Dunn was again handed the starting job behind the plate, this time with a strong veteran staff to work with. Al Demaree won 24 games and Heinie Berger joined the staff to win 19 as the Gulls battled Birmingham for the title. Dunn drew raves for his defense. Manager Frank Chance of the Cubs described Joe as “a nice clean ballplayer and a beautiful thrower.” Dunn raised his average to .207 in 105 games as the Gulls finished second, 6½ games behind Birmingham. In the offseason Finn swapped Dunn to the Tigers for catcher Charley Schmidt. The Tigers in turn sold Dunn to Seattle, but Joe balked. Dunn was returned to Mobile’s roster and eventually his contract was sold to the Southern League rival Atlanta Crackers for $500. Atlanta manager Billy Smith called Dunn “the headiest catcher in the league.”

The 1913 Crackers fell into fourth place by the start of June. Smith started playing Dunn more often and gave him credit for keeping the pitching staff on target and playing solid defense. Down the stretch the Crackers pulled close by reeling off 19 wins in 21 games (plus 2 ties) and eventually passed Mobile and finished in first place by half a game. Dunn returned to Atlanta for the 1914 season and found himself getting more playing time because, according to Smith, “he seemed to be getting better with age.” The Crackers were not as strong as in 1913 and injuries took their toll on the way to a fourth-place finish.

In the fall of 1914 businessman Joe Gardner became the new owner of the Dallas franchise in the Texas league, and he hired Joe Dunn as player-manager. Gardner proclaimed that “Dunn will do great work in developing young pitchers.” One of them, 18-year-old Neal Brady, ended the season with a 20-12 record in a whopping 382 innings and earned a call-up to the majors with the New York Yankees. But though most minor-league managers of the time had the autonomy to sign players and construct their roster to their liking, Dunn did not have that luxury. He had to make do with what scout Don Curtis sent him or with pickups from other teams. It was a valuable lesson for the rookie manager and made him aware of the necessity to network with friends and acquaintances in order to build teams in the future.

Dallas got off to a slow start, but Dunn worked hard trying out different players and looking at new pitchers. He butted heads with owner Gardner, who, according to The Sporting News “crossed Dunn on many occasions, especially in the selection of pitchers.” Meanwhile, Dunn was also the regular catcher and appeared in 110 games. On May 1 Dunn was involved in an incident that would repeat itself in later years. The catcher for the Galveston team, Fred Dilger made an insulting comment about Dunn’s membership in the Knights of Columbus, upon which, according to the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Dunn “landed a right jab on Dilger’s left ear.” Teammates and the umpire stopped the fisticuffs and both players were ejected. By mid-June, Dunn had sorted out the line-up and the team moved up to fourth place. Dallas finished in fourth place and Dunn, tired of the owner’s interference, let it be known that he would not return to Dallas the next season.

Dunn soon found employment for the 1916 season when he signed to manage and catch for his hometown Springfield Reapers of the Central League. After bad weather in the spring, the Reapers played poorly to begin the season. But slowly the team began to round into shape behind a pitching staff of Jesse Haines and Lefty Lowdermilk. The Dayton Veterans took the first-half crown, but Dunn had his team ready for the second-half race. Haines had a superb season and the Reapers won the second-half title, though they lost the postseason playoff to Dayton in six games.

In November Joe was married to Katherine “Kitty” Fahey in St. Joseph Church in Springfield. They had four children, the first of whom was Joe, Jr. born in 1919. From 1920 on, the family spent the season wherever Dunn was managing. Daughter Kathleen remembered, “He always had a beautiful home for us.” Robert was born in 1922; Kathleen in July of 1924 (in Evansville, Indiana, where Joe was managing); and Edward in 1930. Joe,,Jr. was a bombardier in World War II and a graduate of the University of Dayton. Robert was very athletic, but died at the age of 16 after a sports injury led to pneumonia and a blood clot. Kathleen got a degree as a dietician from Mount Saint Joseph College in Cincinnati and worked at the Springfield Community Hospital for decades. Edward, an excellent athlete, graduated from Wittenberg College and got a law degree from Georgetown. As of 2010, he still practiced law in Springfield.

Dunn returned to pilot the Reapers in 1917. Jesse Haines was joined by a rookie, Joseph Coffindaffer, to form a potent one-two punch on the hill. Another excellent recruit was outfielder Frank Walker, who won the triple crown with a .370 average, ten home runs and 161 runs batted in. After playing a career high 120 games in 1916, Dunn spent more time in the dugout and played in 71 games. His days as a number one catcher were over, as he spent more time as a bench manager. The Reapers led the league until mid-June, when the Grand Rapids Black Sox overtook them. The Reapers played almost.600 ball (74-50), but they weren’t able to keep pace with Grand Rapids, finishing six games back. Financially, the ownership did well, with many of the players being drafted or sold to higher classification teams.

After the season Dunn went to work for his brother the postmaster awaiting an offer for a baseball position for 1918. He eventually accepted an offer from the Salt Lake City Bees of the Pacific Coast League to be the backup catcher in a wartime climate that made it difficult to keep players. The catching job paid Dunn more than his manager’s job. The federal government’s Work or Fight order gave local draft boards the right to order men into specific jobs or draft them for the military. The Bees were at .500 when the PCL disbanded on July 14. It’s not clear whether Dunn, 33 years old, fell under the Work or Fight order, but he took a good-paying job at a shipyard in Portland, Oregon, where he could also play ball on Saturdays and Sundays. (Bees manager Buddy Ryan also took a job at the shipyard.) Later he moved to a shipyard in Seattle, where he worked and managed a local team.

In April 1919, World War I was over and Dunn was hired to manage and be the backup catcher for the Bloomington Bloomers in the Three-I League. The league had disbanded in July 1917 and was getting back into business along with many other minor leagues. The scramble for players was intense and Dunn called upon all his connections to put a squad together. Over the years his best connections were with Billy Smith from his Atlanta days, Hughie Jennings and the Detroit organization, and veteran manager Ducky Holmes. One of Dunn’s early signings was 21-year-old Butch Henline, who handled most of the catching and went on to an 11-year major-league career, followed by four years as a National League umpire. Bloomington finished 80-41 and won the pennant by 15 games.Dunn returned to Bloomington in 1920, and his team won the pennant with an 82-57 record. After the season the team barnstormed the state of Illinois and also had home matches with Indianapolis and St. Louis. The Bloomington Daily Pantagraph reported in September that Dunn had been offered a job with Columbus of the American Association and that the Philadelphia Phillies had also contacted him. He was also reported to be a finalist for the Detroit job that went to Ty Cobb. Dunn opted to stay with Bloomington for 1921.

After two titles Dunn had to cope with a great deal of turnover; he had little success finding the right combinations, and the Bloomers finished in sixth place (65-69). He decided not to return to Bloomington for another season. The Springfield Daily News reported that he “has been swamped with offers.” At the minor-league winter meetings in Buffalo, Dunn accepted an offer from the Joplin, Missouri, team of the Western League. The Joplin franchise fell apart in the winter of 1921-22 and was transferred to Denver, but without much of its talent. With the team’s record at 16-26, Dunn resigned in June. (The Bears limped to a final record of 63-105.) Dunn caught on as a scout with Detroit and was on a scouting trip to Toronto when the Birmingham Barons contacted him and asked him to replace manager Carlton Molesworth. The team was 40-44 when Dunn arrived on July 11. They finished 74-80 in a grueling season that included a 12-game losing streak. In October Joe signed to return for the 1923 season. He had a good lineup and pitching staff and hopes were high. But the Barons got off to a slow start and were under .500 in late May, when Dunn resigned as manager. The Sporting News reported that clubhouse dissension was an issue. Dunn’s children said the Ku Klux Klan burned a cross in the Dunns’ yard because they were Catholics. After that Kitty had no desire to stay in Birmingham. The children attributed the clubhouse dissension to Johnny Neun, Dunn’s first baseman. It is uncertain whether this was personal or KKK-related. Dunn left Birmingham with an 18-28 record and returned to Springfield.

The Evansville Pocketeers of the Three-I League brought Dunn in to manage in 1924. He assembled a talented, fiery, maybe even hot-headed squad. There were numerous run-ins with umpires. In one game an Evansville player even refused to leave the field when ordered, yet the game continued. It was suggested by rival newspapers that Dunn was responsible for a “riot” on June 21 when fans attacked the umpires. There was even a move to oust him from the league. The Pocketeers were in the pennant race until the last series, when they were swept by Bloomington, and finished in second place. The 1925 version of the Pocketeers featured only three holdovers from ’24 and won 72 games, but finished in third place.

Dunn moved on to Elmira in the New York-Penn League for the 1926 season. The Colonels had the worst attendance in the league in 1925 and Dunn was brought in to improve the team. He kept only three starters from the previous year. The Colonels were a feisty bunch, emulating their manager. On June 20 in a game against Scranton, state troopers had to be called in to break up a fight. The scrappy Colonels stayed close in the pennant race into August, when they tailed off and dropped to fourth, finishing with a record of 68-67. Dunn made his last appearances as a player that season, coming into three games. He agreed to return to Elmira for 1927. After another rebuilding job, the team hovered near .500 most of the year and finished in fourth again with a 67-73 record.

In 1928, Dunn helped bring professional baseball back to his hometown of Springfield, Ohio. The city had been without a team since 1917 and the Central League had folded in 1922.Dunn was instrumental in reviving the league in 1928, and he and his siblings Charles and Katherine formed the Springfield Baseball Club Inc. They then transferred some of their stock to Frank Navin, owner of the Detroit Tigers, in return for $5,000 to be used as operating expenses. Navin also got a cut of the concessions and first-refusal right on any players Dunn signed. The club rented Eagles Field in Springfield for $3,000 for the season and sold the concessions rights to the Jacobs Brothers of Buffalo, New York, for $3,000. The revived Central League played a split season, with Fort Wayne winning the first half and Erie taking the second-half title. The Springfield Buckeyes finished with a combined record of 67-66, the fifth best overall record. In 1929 the team renamed itself the Dunnmen, and barely avoided the cellar with a 59-77 record.

The 1930 team adopted the nickname Blue Sox. Dunn was determined to build a winning team and put together an offensive juggernaut. The Blue Sox won both halves of the season and finished with a combined 82-55 record. But the Depression took its toll and the team lost money. Dunn was often heard in later years saying, “You can’t make money owning a baseball team.” The Central League folded after the 1930 season. Dunn was advised to declare bankruptcy and avoid the debts he had incurred during the past few years. His sense of honor did not allow that and it appears he made good with his creditors over time. Needing to be employed and not wanting to be out of “the game,” Dunn returned to the Three-I League in 1931, catching on as manager at Bloomington. The city was excited about Dunn’s return because “he likes fighting ballplayers. …He always has been that way.” The league ran a split season. After a slow start, the team finished 27-22 in the first half, but trailed Springfield. In the second half the record dropped to 31-39 and they never challenged second-half champ Quincy. Economic woes cost Bloomington its franchise for the 1932 season. The league itself started with six teams, but disbanded on July 14 after two teams dropped out. Dunn found employment as the general manager of Hazleton in the New York-Penn League. He worked there until the fall when he sent out contract offers and then returned to Springfield. As fate would have it, the Hazleton club folded before the start of the 1933 season.

Back in Springfield, Dunn took a job as district manager for Shell Oil. He stayed with the company until 1942 and was active with baseball in town. He continued to attend the major- and minor-league winter meetings, always hoping for a job offer in the big leagues. Edward Dunn remembered seeing his father open a letter from a major-league club one day and seeing his shoulders slump. The letter contained an offer, but only to manage in the low minors. After leaving Shell Oil, Joe worked as a supervisor for the Robbins and Meyers Mfg. Co. and coached their company team in Springfield. On Sunday, March 19, 1944, the Dunn family went to Mass. During the service, Joe became ill and was taken to the nearby Bancroft Hotel. He died in the lobby of a heart attack. He is buried in Calvary Cemetery in Springfield. His wife, Kitty, continued to live in the family home until her death in 1968.

Sources

I am indebted to Joe’s children Edward and Kathleen, who graciously spent time with me and provided me with clippings from throughout Joe’s career. They also shared a family tree and a copy of the stock certificate transferred by Charles Dunn to Detroit owner Navin. Edward found this for sale on eBay.

A tip of the hat to SABR member Mark Miller who suggested Dunn as a topic and who provided a great deal of research about Springfield baseball.

Baseball-Reference.com

Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball

Various Spalding and Reach Guides

The Sporting News

Newspapers from Springfield, Ohio; Columbia, South Carolina; Roanoke, Virginia; Dallas, Texas; Evansville, Indiana; Bloomington, Illinois; Mobile, Albama; Montgomery, Alabama; Atlanta, Georgia; Elmira, New York; Denver, Colorado; and Salt Lake City, Utah.

Full Name

Joseph Edward Dunn

Born

March 11, 1885 at Springfield, OH (USA)

Died

March 19, 1944 at Springfield, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.