Sam Jones

Sam Jones was an intimidating pitcher. He was big (6 feet 4 and 200 pounds), threw hard, had a massive sweeping curveball, and could be quite wild. Three times he led the National League in both strikeouts and walks (1955, 1956, and 1958). He narrowly missed this feat a fourth time in his finest season, 1959, when he was the NL’s Pitcher of the Year. In 1955, Jones became the first African-American major leaguer to throw a no-hitter. He could have had at least two more, barring a dubious scoring decision and a fierce storm.

“Toothpick Sam” — he always had one in his mouth — gave no quarter on the mound. Valmy Thomas, his catcher in Puerto Rican winter ball, recalls how Jones warned any batter who crowded the plate, “[Expletive deleted], cover it up!” Sam squared off with Don Newcombe, Rubén Gómez, and Don Drysdale in knockdown duels and payback plunkings. Yet he disclaimed the “headhunter” tag. He stated, “I was always worried I might permanently hurt someone. . . .I just don’t believe in the beanball.”1

The mournful-looking Jones was also known as “Sad Sam,” echoing the AL hurler of 1914-35. He didn’t talk much and mumbled when he did. He had quirks: He was afraid of airplanes and snorted like an old horse because of a sinus condition. Off the field, Sam was an amiable man, generous to teammates and fans alike. Hobie Landrith, who caught the righty for six seasons (1956-61), said it well. “He wasn’t very expressive, he wasn’t the gregarious type, (but) he injected humor.”2

In a pro career that spanned 22 years (1946-67), Jones played in the Negro Leagues and in four other Caribbean nations: Panama, Venezuela, the Dominican Republic, and Nicaragua. He was in the majors for eight full seasons (1955-62) and parts of four others (1951-52, 1963-64). His last four summers were spent as a player-coach in the minor leagues.

Sam came to the game late and needed time to harness his talent. With his shambling gait, he wasn’t a graceful athlete. He faced still more obstacles. It took him years to find an opening in the majors, and once he did, he got a largely undeserved reputation as “not a winner.” Often saddled with low run support and shaky fielding, he seemed to catch more than his share of bad breaks. Alas, this hard luck followed him into retirement. Just four years after he hung up his spikes, Jones passed away from a recurrence of cancer.

Samuel Jones was born Daniel Pore Franklin in Stewartsville, Ohio on December 14, 1925. Although the Social Security Death Index gives the year as 1923, census records and Sam’s gravestone show 1925, in line with baseball reference books. However, various newspaper articles over the years hinted that Jones might have been shaving years off his age for professional purposes.

The more interesting aspect is this man’s name at birth. The release of 1940 census data in 2012 shed light on his family background, where details had been lacking. His mother, Athelestine Jones, was born in Alabama around 1909. Her unusual given name and the fact that she was still living in Stewartsville in 1935 reveal her four-year-old son in the 1930 census – under the name Sam Franklin. Athelestine was married in her teens, but his father, John Franklin, was no longer with the family by 1930. A childhood friend named Robert Armstead, who later wrote a memoir about his life as a coal miner in West Virginia, said that Sam looked just like his mother – but never knew his real father.3

Another topic was never really brought out in the open while Sam was playing. His very light tan complexion, green eyes, and facial features all bespoke a biracial mix — think of Derek Jeter or basketball star Jason Kidd. Another indicator here was his reddish hair, which won him the early nickname Red (though it would recede over time, leading him to sport a porkpie hat indoors or out4). At the time, newspapers simply called him “a light-skinned Negro.”

As of 1930, Athelestine (still also known by the Franklin surname) was in the home of her father, Charles Jones. Sam had no other siblings at that time, though his teenaged uncle and aunt were also under the same roof. Charles, who worked as a loader in the Stewartsville coal mines, was a father figure to his grandson. He was represented simply as Sam’s father in articles written during the pitcher’s career.

Sometime between the ages of 10 and 12, Jones moved with his family to West Virginia. Robert Armstead remembered that his friend was the state champion marble shooter in West Virginia in 1937. “They gave him fifty dollars and a brand new bicycle. To us poor young black boys, Sam’s victory was incredible. . .His determination and skill made him an even greater celebrity twenty years later.” 5

Work took Charles Jones to Monongah, a coal company town that was the scene of the worst disaster in American mining history, in 1907. The industry’s hazardous conditions were little better during the Great Depression, as Mountaineer novelist Davis Grubb grimly depicted in his book The Barefoot Man. Still, with times as tough as they were, fathers accepted the risks despite the paltry pay. This set the tone for noted sportswriter Dick Schaap’s warm portrait of Sam Jones — as a pitcher and as a man — in a 1960 special feature for Sport magazine. Schaap told how calamity loomed:

“Sam can think back to his 13th year and remember the day his father went off to work and there was an explosion and his father didn’t come home. He can still see his father-in-law twisted into a wheel chair, sentenced by a cave-in to paraplegic anguish and helplessness. Sam Jones knows the coal mines all right.”6

As of 1940, Athelestine was married again, to a much older man named Amos Wilson who was also a coal loader. They and Sam lived in a poor neighborhood known as The Bottom in the neighboring community of Grant Town.7 Fortunately, Sam himself never had to descend into the mines. He played football and basketball at nearby Fairmont High School, although he left school early. However, except for games of catch with Robert Armstead’s father (who showed him a knuckleball and curve), Jones had very limited exposure to baseball.8 He did not play with teams — even in the sandlots — until he joined the Army around 1943 (records have been lost). He was stationed in Orlando, Florida; during World War II, some Army personnel served at the Orlando Army Air Base and nearby Pinecastle Army Air Field. Sam played not for the post team, which was still white-only, but for a team fielded by one of the base’s smaller units that was actually stronger. His positions were first base and catcher; he pitched only on occasion.9

In the service, this man who neither smoked nor chewed tobacco — at least then10 — also acquired his defining habit: chewing toothpicks. “He began by chewing match sticks, but they were too expensive and the sulphur tips ruined his appetite. ‘They’ve got to be flat. They’re the only kind to chew. The round ones are too hard. The flavored ones don’t taste good. I’ve tried peppermint, cinnamon, even strawberry — they can’t touch a plain old flat one.’”11

The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues states that Sam played for the Homestead Grays in 1946. This has been repeated elsewhere — but various articles in the Oakland Tribune show that from April until at least mid-July, he was pitching for the Oakland Larks of the West Coast Baseball Association. This short-lived Negro League folded during its first season. Its president was Harlem Globetrotters impresario Abe Saperstein, and its vice president was the great Olympic track star Jesse Owens.

Jones may also still have been in the Army Air Corps that year, perhaps before he joined the Larks, and possibly afterward as well. On the side, he was playing with the Orlando All-Stars, a town team in the Florida State Negro League.

In 1947, Jones signed to play with the Cleveland Buckeyes of the Negro American League. Veteran catcher Quincy Trouppe (who added a second “p” to his family name in 1946 while playing in Mexico) was the club’s manager. By some accounts, Trouppe was the man who got Sam to leave the Army and turn pro, though that does not account for his time in the WCBA. In Dick Schaap’s account, the Buckeyes faced the All-Stars in 1947, and Trouppe “liked the way Jones handled himself.” He promised the soldier $550 a month, more than five times his Army salary, and painted a colorful picture of the baseball life. Eventually Quincy convinced Sam as well as his company commander. Jones forsook becoming a “twenty-year man,” withdrew his re-enlistment, and was mustered out. In July 1947, he became a Buckeye — and he was a full-time pitcher, as he had been with the Larks. He wasn’t a good hitter, and besides, “Quincy was the catcher, and there wasn’t no sense trying to beat out the manager.”12

Record books indicate that Red (whose teammates allegedly found him lacking in social graces13) was 4-2 for Cleveland that year. However, almost no box scores of these games were published, and limited statistics were kept. A Sporting News feature on Sam in June 1951 gave his ’47 record as 6-3, which is possible.14 The won-lost total of all the Buckeyes pitchers listed in The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues was 44-17, whereas the team overall was 54-23.

The Buckeyes were champions of the Negro American League, or West. The lineup was anchored by two other men who would go on to noteworthy major-league careers: outfielder Sam Jethroe and Al Smith, then a shortstop. The ace of the pitching staff was wily 40-year-old Chet Brewer. They faced the Eastern champs, the New York Cubans, in the Negro World Series. The opponents featured future major leaguers Orestes “Minnie” Miñoso and Rafael “Ray” Noble, as well as another native Cuban, Luis Tiant, Sr. Pat Scantlebury from Panama, who would pitch in six games for the Cincinnati Reds in 1956, had a 10-5 record to go with Tiant’s 10-0.

The Cubans won the series in five games after the opener at the Polo Grounds was called because of rain. The makeup game was played before about 9,000 fans at Yankee Stadium, but subsequent matches were played before very small crowds in Cleveland (Municipal Stadium, not League Park, where the Buckeyes played), Philadelphia (Shibe Park), and Chicago (old Comiskey Park, where the Negro Leagues’ East-West All-Star Games took place).15

Sam’s only inning of work came in Game Three at Cleveland. The Cubans broke open a 0-0 tie with six runs against him in the ninth, on a double, three singles, a walk, and an error.16

Returning to the Buckeyes in 1948, Jones posted a 9-8 record — or possibly 13-8, as noted in the June 1951 Sporting News article. Again this is feasible, based on the team’s total record of 41-42 and the aggregate record of 26-27 for pitchers listed in The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues. Quincy Trouppe had moved on to the Chicago American Giants; Cleveland’s new manager was Alonzo Boone. After stumbling to a 5-13 start, the Buckeyes then played .750 ball over their next 36 games to finish the first half in second place at 32-22.17

But just over a week later, on July 13, the team lost their two best everyday players, and a predictable skid ensued. Sam Jethroe went to the Dodgers’ organization, while Al Smith signed with the Cleveland Indians. The club’s financial woes no doubt contributed; Jones for one “seldom received the $550-a-month he had been promised. ‘More like $50 to $75 and promises for the rest.’”18

Sam himself got a first look from the Indians in 1948 — but an unnamed scout dismissed him with a brief “Won’t do.”19 That summer a writer friend in Cleveland told the raw pitcher that he would need a good change of pace to make it to the majors. Red protested that he did have one, but the writer candidly told him that he was telegraphing it. A few years later, “with triumph in his voice, Jones told the writer, ‘I’ve got a good one now! Look at those box scores!’”20

After the ’48 season ended, Sam joined the Kansas City Royals, a touring Negro League squad handpicked by Satchel Paige.21 The opponents included teams headed by Paige’s teammates on the World Series champion Indians, Bob Lemon and Gene Bearden. The venues included Wrigley Field, and the crowds were respectable, reaching over 13,000.22 However, no record has surfaced of any appearance by Jones.

In November, Sam signed to pitch in Panama with the Spur Cola Colonites, one of four teams in that nation’s former pro league. Edric “León” Kellman, the Panamanian third baseman of the Buckeyes, managed the team and was almost certainly the man who brought Jones down. Pat Scantlebury was the ace of the staff. The race was exciting, as a berth in the inaugural Caribbean Series was at stake. Although the season did not end until March, the leader as of February 12 represented Panama, since the tournament was set for February 20-25.23

As the week of February 7 began, Spur Cola needed to win four out of five games. A three-way tie with Carta Vieja and Chesterfield was possible. Sam was instrumental in this stretch, beating Chesterfield with a strong relief effort and clinching the lead on the evening of February 12 with a win over last-place Cervecería that brought his record to 4-5.24 He added at least one more win in March, a two-hit shutout.25

Panama (2-4) finished third behind undefeated Cuba and Venezuela in the 1949 Caribbean Series, which was played in Havana. Sam was 1-1, as he dropped a 4-2 decision to Venezuela’s Caracas Leones on February 21 but came back three days later to beat the same club, 3-2. He struck out 10 in his 17 innings pitched.26

In 1949, the Negro National League had disbanded and the Negro American League was moribund. Jones left for the Southern Minnesota League, a strong semipro circuit. Ben Sternberg, manager of the Rochester Royals, signed Sam thanks to his connections with Abe Saperstein. Saperstein, owner of the Harlem Globetrotters basketball team, was also active as owner and booking agent in the Negro Leagues.27

Jones became the Southern Minny’s most feared pitcher. He won 10 and lost just two during the regular season, including a 12-3 no-hitter over Owatonna on August 4 that featured 12 strikeouts, six walks, and five errors. Dick Schaap’s story stated that Sam’s record was an astonishing 24-3 that year, as did the 1951 Sporting News article. However, Armand Peterson, co-author of Town Ball: The Glory Days of Minnesota Amateur Baseball, shows how this was not possible. So, looking back again at Sam’s Negro League numbers from 1947 and 1948 as reported by The Sporting News, that’s another reason to take those with a grain of salt.

Peterson combed through the Rochester Bulletin on microfilm to record all box scores and line scores for the Royals. The league played a 35-game schedule that year, with a few exhibitions. Jones pitched his first game for the team on June 12, so it was remarkable that he got as many decisions as he did. Rochester was 3-7 before Sam joined the staff but went 18-7 thereafter, as the workhorse either started or relieved 18 times before the regular season ended on August 16.

Jones was 3-2 in the playoffs. He won twice in the semi-finals but lost the first game of the finals against Austin (home of Hormel Foods and SPAM®), 4-3. In the second game — six days later because of two rainouts — he threw another no-hitter, striking out 15 and walking seven. Then, down two games to one and facing elimination, Rochester used its ace on one day’s rest because its second starter had to leave for his high-school teaching job. Sam was knocked out in the seventh inning, and the Packers took the title, 6-1.28

That fall, Jones entered “Organized Baseball.” Wilbur Hayes, business manager of the Buckeyes, had kept lobbying Hank Greenberg of the Indians on his pitcher’s behalf. Greenberg, then farm director and later general manager, remained doubtful but agreed to bring Sam in for a tryout in November. His eyes were quickly opened.

“I saw this big fellow pitch, and it was hard for me to believe what I saw. Here was a fellow, 23 years old, who had never played organized ball and he could do things with a baseball that many of our veterans couldn’t do. He had an overhand curve and a side-arm curve. And speed! What speed! How our scout was able to make such a completely incorrect report I’ll never understand.”29

Laddie Placek, Cleveland’s supervisor of Ohio scouts from 1947 to 1961, is credited with the 1949 signing. It is not clear whether Placek, who also got Al Smith and Joe Caffie from the Buckeyes for the Indians, was the one who thought Sam didn’t have the goods the previous year.

Jones pitched for Spur Cola again in the winter of 1949-50. Although information on that season is also scanty, he threw at least two shutouts. Joining him on the staff that year was another Panamanian comrade from the Buckeyes. Lefty Vibert “Webbo” Clarke, who would appear in seven big-league games for the Washington Senators in 1955, had pitched the previous year with Chesterfield.30

Upon his return from the isthmus, Sam married his hometown sweetheart, Mary Beans, whom he had known from high school, on February 26, 1950.31 They had two sons: Sam Jr., later known as Nick (born 1952), and Michael (born 1954).

Jones helped the Wilkes-Barre Barons win the championship of the Class A Eastern League in 1950. His 17-8 record included a 9-0 start. He led the league in strikeouts with 169, and his 2.71 ERA ranked second. He finished second in the voting for the Eastern League’s most valuable pitcher to his teammate Bob Chakales, the ERA champ.32 “Didn’t throw nothing but fastballs there,” Jones recalled. “Didn’t need nothing else.”33 It was also in Wilkes-Barre that local sportswriter Bill Phillip dubbed him Sad Sam.34

In the winter of 1950-51, the Panamanian league was tightening its belt. Spur Cola and Chesterfield both sought to trim payroll and use players from lower classifications. Pat Scantlebury held out for more money but eventually decided to play. After an initial indication that he might join the roster, Sam did not come down.35, 36

Spring 1951 saw Jones in camp with the Indians, but on March 9 he was assigned to the San Diego Padres of the Pacific Coast League. On March 31, the Long Beach Press-Telegram observed, “Cleveland writers accompanying the Tribe were amazed when manager Al Lopez decided to leave him with the Padres. They thought he was good enough to stick. . . . and that can be taken as a tip that Sad Sam may become the whirlwind of the coast this summer.” (Also of interest: that article gave Sam’s age as 28.)37

Jones did have a strong if not extraordinary year. After a 9-4 start, which included a couple of tough shutout losses, he finished 16-13 with a 2.76 ERA. He struck out a league-leading 246 batters in 266 innings, and his 21 complete games also led the PCL. “Rogers Hornsby, then managing Seattle, insisted, ‘Jones is the best pitcher in the whole minor leagues.’”38 The Los Angeles Mirror called him “a poor man’s Bob Feller”; Hollywood Stars manager Fred Haney said, “That’s no baloney. He throws just like Bob Feller when Bob broke in.”39

Feller himself had taught Sam how to mask his pitches in spring training that year. Jones worked on this further in San Diego, noting, “Every time I threw a curve, my thumb was sticking up in the air. I fixed that right away. Got my thumb down.”40

The development of the big-breaking Jones curveball is more intriguing. Sam gave initial credit to Satchel Paige, whom he beat 1-0 in 1947 while Satch was with the Kansas City Monarchs. Said the master to the rookie after the game, “You’ll be a good pitcher, boy — but you got to know how to make a ball move around. You ain’t going nowhere with just you and a fastball.”41

Aside from the brief barnstorming tour in the fall of 1948, Paige and Jones were never on the same roster. Satch played for the Monarchs in 1947 and the first half of 1948, until the Indians signed him that July 7. Jones made good use of their occasional contact, but credit is also due to Buckeyes teammate Chet Brewer, who “worked long and hard in an effort to put a bend in Sam’s pitch.”42 Brewer was also noted for a sweeping curve. Bob Feller, by then relying more on his curve, lent a hand as well with the Indians. In later years, though, Jones would state that Cleveland’s first-rate pitching coach, Mel Harder, helped him master “Number Two.”

On August 18, 1951, the Padres staged Happy Sam Night to try to change their pitcher’s luck after a losing streak.43 It helped that night and more — the Indians called Sam up in September. He made his debut on September 22 in relief at Detroit, getting the last two outs in the eighth inning as the Indians lost, 9-4. His first major-league start came on the last day of the season against Detroit. Sam lost a tough 2-1 duel, as he walked the bases loaded in the seventh. The last pass was intentional, but opposing pitcher Virgil Trucks foiled the strategy by looping a two-run single to left.44

“You’ll see a lot of Sam Jones,” said Indians manager Al Lopez after the season. “I like a fastball pitcher for relief. So Sam could help us in the bullpen, as well as become a starter. He hides his pitch very well.”45

Jones pitched in the Puerto Rican Winter League in the winter of 1951-52. With the San Juan Senadores, he had a fine season: 13-5, with a 2.51 ERA. His 146 strikeouts in 167 innings led the league. Sam had a rivalry with Rubén Gómez of the Santurce Cangrejeros (Crabbers), his future opponent in the NL too. In one late-season game, in a play at the plate, Gómez spiked Jones in the knee.46 Rubén led the league in wins and captured the MVP award that winter — but Sam’s Senadores were league champs that year.

After pitching well over 400 innings in 12 months, Jones reached the point of critical overload late in January 1952. With a one-hitter going into the ninth inning against Santurce, Sam reached back to try to strike out the Crabbers’ Johnny Davis — and felt a sudden pain in his arm. It turned out to be bursitis (if not more), which he tried to nurse along with a sling, heating pads, and hot towels, and daily rubdowns from wife Mary.47

Despite his ailment, Jones reported for spring training, but he left camp for a while to rest the arm. Upon his return, he remained on Cleveland’s roster (aside from a brief end run around the 25-man limit in July) until being optioned to Triple A Indianapolis on August 18. With Cleveland he was seldom used, starting just four times in 14 outings. The results were poor too: 2-3, 7.25 ERA, 37 walks and six homers in 36 innings. Clearly the bursitis (which he downplayed as “just a touch”48) was still plaguing him, but he refused even to consider surgery.

However, a historical footnote came in Sam’s first game that year, on May 3. When he entered in the seventh inning against the Washington Senators, behind the plate was his old Buckeyes manager, Quincy Trouppe, making one of his six major-league appearances at the age of 39. They formed the first black battery in AL history.

Sam pitched the 1953 season with Indianapolis in the American Association. He had gone 4-0, 3.09 for Indy at the end of the previous summer, with Trouppe as his receiver. Jones posted a so-so record in ’53 (10-12, 3.32) and did not see any major-league action. The arm was still bothering him — but beyond that, it was simply impossible to crack the Big Four Cleveland rotation of Bob Lemon, Early Wynn, Feller, and Mike Garcia.

That winter he pitched with the Maracaibo Gavilanes in Venezuela, which then had four teams in its league. The manager was Indians coach Red Kress, who brought along various Tribe prospects at the suggestion of Hank Greenberg.49 The GM had reversed his prior stand against winter-league ball, which Sam’s sore arm had prompted.50 Playing shortstop for the Gavilanes was a local — Luis Aparicio, replacing his father (also named Luis) in his first pro season. It was not a successful time for Jones, though, as his control again deserted him. In 48 innings over seven games, he walked 38 men, allowed 43 hits, and struck out only 18. This led to a 2-4 record and 5.06 ERA.

Sam returned to better form in 1954: 15-8, albeit with a 3.75 ERA, despite four shutouts. Yet he remained stuck at Indianapolis and grew disenchanted. “In September 1954 he was fed up with his treatment by the Indians and threatened once again to quit. The Minneapolis Tribune quoted him as saying that ‘if I don’t get a major-league job next summer, I’m going to quit organized baseball and make my home in Rochester. I like it around there and I can pitch in the Southern Minny League.’”51

On September 30, the Indians finally dealt Jones, sending him to the Chicago Cubs (along with $60,000 and Gale Wade, as it developed) for a player to be named later. That player turned out to be Ralph Kiner, the Hall of Fame slugger, who had just one season left in him because of his bad back. Kiner was also an old teammate and friend of Hank Greenberg’s.

In the winter of 1954-55, Sam returned to Puerto Rico, this time playing for Santurce. Crabbers third baseman Don Zimmer called it “the best winter league baseball club ever assembled.”52 Managed by Herman Franks, the cast featured Latinos, Negro Leaguers, and both black and white major leaguers. The outfield of Bob Thurman, Willie Mays, and Roberto Clemente was extraordinary. There was quality on the mound too, led by Jones and Rubén Gómez. Sam won the Triple Crown of pitching that season with his 14-4 record, 168 strikeouts in 158 innings, and 1.77 ERA. “This isn’t the Sam Jones that we had,” said Al Lopez. “This Jones can throw hard. The Jones we had couldn’t even lift his arm.”53

Sam won the last game of the league finals against Caguas. The Crabbers then went on to take the Caribbean Series. The tournament’s most exciting game was an 11-inning duel between Jones and Ramón Monzant of the Venezuelan champs, Magallanes. Just past midnight, Clemente singled and Mays homered to give Puerto Rico a 4-2 win. Sam was named to the series All-Star team.54

In 1955, nearing if not over 30, Jones finally got his chance in a major-league rotation. The Cubs were a sub-.500 team at 72-81. This had a bearing on Sam’s record: 14 wins, 20 losses (most in the majors), 4.10 ERA. However, his wildness was pronounced. He walked 185 and hit 14 batters in 241⅔ innings pitched, leading in both those categories as well as in strikeouts (198).

On May 12, before a sparse crowd of 2,918 at Wrigley Field, he threw his no-hitter against the Pittsburgh Pirates. It was the first one at Wrigley since Fred Toney and Hippo Vaughn faced off in their double no-hitter of May 2, 1917. . .and it didn’t come easily.

Sam had thrown 109 pitches through eight innings, with four bases on balls. To start the ninth inning, he walked Gene Freese, pinch-hitter Preston Ward, and Tom Saffell. Cubs manager Stan Hack was on the point of pulling his pitcher, but veteran catcher Clyde McCullough barked at Hack to keep him in. Jones then proceeded to strike out Dick Groat (who fanned only 26 times all that year), Roberto Clemente, and Frank Thomas on 11 pitches to preserve his gem. Accounts vary, but allegedly it was only when Thomas got to the plate that Sam realized from the crowd noise that he was on the verge of a rarity. Even with the bases loaded, he fed the slugger nothing but curves.

Sam had thrown 109 pitches through eight innings, with four bases on balls. To start the ninth inning, he walked Gene Freese, pinch-hitter Preston Ward, and Tom Saffell. Cubs manager Stan Hack was on the point of pulling his pitcher, but veteran catcher Clyde McCullough barked at Hack to keep him in. Jones then proceeded to strike out Dick Groat (who fanned only 26 times all that year), Roberto Clemente, and Frank Thomas on 11 pitches to preserve his gem. Accounts vary, but allegedly it was only when Thomas got to the plate that Sam realized from the crowd noise that he was on the verge of a rarity. Even with the bases loaded, he fed the slugger nothing but curves.

Cubs’ TV announcer Harry Creighton had joked with Sam during batting practice that he would buy him a gold toothpick if Jones threw a no-hitter; after the game, Creighton spent $11 to honor his pledge.55 Family man Sam’s first act, though, was to call his wife.56

Jones was named to the National League All-Star team in ’55. His brief eighth-inning stint was a microcosm of his season: He struck out Mickey Mantle, got Yogi Berra to foul out, but then hit Al Kaline and added two walks before Joe Nuxhall retired the side.

The 1956 campaign was subpar overall for Sam (9-14, 3.91), even though he led the NL again in strikeouts. On December 11, the Cubs sent him to the St. Louis Cardinals in a nine-player deal. “I’ve always had trouble hitting against him,” said the great Stan Musial. “I’m glad he’s on our side.”57 The feeling was mutual. General manager Frank Lane also liked Sam’s talent, promising him a gold-and-diamond toothpick if he won 20 games.58

With the Cards, although a sore elbow troubled him, he enjoyed a fairly good season in 1957: 12-9, 3.60. He went 14-13 in 1958, with a club-record 225 strikeouts, breaking Dizzy Dean’s 1933 mark. His 2.88 ERA was second in the NL behind Stu Miller. St. Louis manager Fred Hutchinson liked Sam, calling him the best pitcher in the National League.59 The former Tigers pitcher refined the big man’s herky-jerky mechanics: Sam streamlined his windup, focused his head on the plate, and used his weight better.60 On the other hand, Frank Lane, who called Jones “a calculated risk” when he dealt for him, was no longer a backer. He later said, “Jones would be great if he had ambition. He had all the natural equipment. But he had a tendency to be lazy. He seemed content to win three or four more than he lost every year.”61

However, Trader Frank was not speaking from firsthand knowledge in 1958. He had moved on to Cleveland in the AL; Bing Devine replaced Lane as Cardinals GM in November 1957. On March 25, 1959, Devine traded Sam to San Francisco in a four-player swap. Budding star Bill White, who was stuck behind Orlando Cepeda, came to St. Louis. The Cards were looking to the future; the Giants wanted to win right then.

“I’m happy as hell,” yelled Giants manager Bill Rigney when he heard about the deal.62 Jones went on to win 21 games that year against 15 losses, the second of the “13 Black Aces” (after Don Newcombe) to have a 20-win season. His 2.83 ERA was the NL’s best. Contrary to Lane’s view, he took the ball whenever Rigney asked, despite the longer-term risk. He started 35 games and relieved in 15 more, with four saves. “What more could he do? He must have thrown 3,000 pitches,” said the skipper.63 Indeed, late that season (September 21), Time magazine profiled Sam in “The Tortured Arm.”

Another example of his competitive fire was visible on August 6, 1959. Against Milwaukee, Hank Aaron’s fifth-inning blooper dropped into short left field. Jim Davenport and Ed Bressoud collided, Aaron motored for third, and Jones covered. Aaron came in hard, spiking the pitcher’s right knee — and driving Sam’s toothpick into his throat. Trainer Bob Bauman dislodged the pick, though, and Jones went on to record a 7-1, complete-game win.64

Sam pitched two innings in the second All-Star Game of 1959, allowing one run. But his most memorable moment from that season came on June 30 at the Los Angeles Coliseum against the Dodgers. Jones was in top form and had a no-hitter through 7⅔ innings. Jim Gilliam of the Dodgers hit a chopper over Sam’s head to shortstop André Rodgers, but the Bahamian, never known for his fielding, bobbled the ball. Yet scorer Charlie Park from the Los Angeles Mirror scored it a base hit, insisting that Gilliam would have beaten it out. Park was alone in his view — his fellow writers were incredulous, and even the LA fans howled. That did little to cheer up a truly sad Sam, who still felt robbed.

In his last outing of 1959, on September 26, Jones no-hit the Cardinals through seven innings. In the top of the eighth, though, menacing funnel clouds danced over Busch Stadium in St. Louis. Then torrential rain and flag-shredding 50-mph gales lashed the park. The game was halted and it went into the books as a no-hitter for Jones. (The achievement was retroactively canceled in 1991, when the major leagues’ rule-makers decreed that a pitcher had to hurl at least nine innings to get credit for a no-hitter.) Despite Sam’s efforts, the Giants faded down the stretch and finished third in the NL that year, three games behind the Dodgers and Braves. He received two votes for the Cy Young award, at a time when there was only one award for both leagues, runner-up to Early Wynn’s 13.

Sam made a special friend that season: an 11-year-old boy named Johnny Bushman, who had moved from a reservation in Montana (his father was a Sioux) to San Francisco. Young Johnny faithfully attended all the Giants games at Seals Stadium, though he didn’t always have the 90 cents to get a bleacher seat. The pitcher had noticed the lad, who wore leg braces as a result of polio, on the fringes of the crowd of kids who would gather around Willie Mays. In his quiet way, he made sure that Johnny got tickets and even admitted him to the clubhouse afterwards.65

Today, John Bushman still has fond and vivid memories of Sam; he feels that the pitcher treated him as a surrogate son while away from his family. Jones would drive him home from the ballpark too. “He gave me the ball from his 20th win that year,” Bushman adds.

That winter, Sam worked once again for a dry cleaner’s shop in his hometown of Monongah — a sign of how modestly paid ballplayers were back then. “I have to work,” he said, but also added that his duties would help keep his legs in condition, as he did a lot of walking on his pickup and delivery route.66 Proprietor Tony Sauro let Jones go out and drum up his own business among the miners, keeping his own hours. He observed that Sam’s memory for people’s addresses and belongings was fantastic.67

In 1960, the Giants gave their ace a raise to $35,000. On Opening Day (April 12), Jones started the first game at the new Candlestick Park. With Vice President Richard Nixon in attendance, San Francisco beat St. Louis 3-1. Four days later, Jones threw another one-hitter; the only man to connect for the Cubs was Walt Moryn with a pinch-hit homer in the eighth.

Shortly thereafter, Sam found that his young friend Johnny Bushman was in San Francisco’s Shriners Hospital after a leg operation. So he went often to see him and the other children on the ward, staying to play pool, sign autographs, and give away caps. “Said Sam, himself the father of two boys, ‘He’s a nice, well-mannered kid. I just like him.’”68 Eleven years later, these visits would have a poignant echo.

The 1960 season was the last in which Jones was a big winner. His 18-14, 3.19 mark included yet another brush with a no-hitter. On May 11, the Phillies got just two fluke hits: a wind-blown bloop double to right by Harry Anderson (sure enough, this game was at blustery Candlestick) and a checked-swing grounder over third by Tony Curry.

After the season, Jones joined the Giants as they toured Japan. The jet-lagged Americans lost the opener, 1-0, to the Yomiuri Giants as Stu Miller allowed a run in relief of Sam and Billy O’Dell. San Francisco then went on to win 11 of the remaining 15 games against a Japanese all-star squad (there was one tie). Jones won three of those and lost none, posting a 0.82 ERA in 22 innings. That was his second trip across the Pacific; the Cardinals had made the previous American tour in ’58, going 14-2 against the Japanese all-stars. Sam had one of those losses but won twice with a 0.47 ERA in 19 innings.

In 1961, Jones dropped off to 8-8, 4.49. He was no longer a full-time starter, coming out of the bullpen 20 times in 37 games. The Giants left him available in the expansion draft after the season, and the Houston Colt .45s made him their 13th selection on October 10. Sam’s take was that he had been “sold down the river” by manager Alvin Dark. He added, “I have to pitch regularly, every fourth day, to be right. My arm was never in good enough shape, being rested that way. If they let me work regular I’ll do a good job for them in Houston.”69 However, the Colts traded him to Detroit on December 1. Tigers manager Bob Scheffing, who was a Cubs coach for the 1955 no-hitter, said, “I know all about him.”70

Sam played in 1962 under the cloud of cancer. In February, during spring training, a baseball writer recounted later, “Jones was plagued with an unusually stiff neck. While massaging the neck one day, trainer Jack Homel noticed two enlarged nodes near the base of the right side. Homel insisted Jones see a doctor and the doctor immediately insisted on an operation.”71 After the March 1 procedure, the initial indication on the “knotty tissues” was benign, but additional tests showed a “low-grade malignancy.”72 Sam underwent cobalt treatments until September, and he went into remission.

The radiation must have been draining, yet Jones still pitched in 30 games (2-4, 3.65), making six spot starts. “He made no alibi, no excuse,” said Scheffing. “All he ever complained to me about was not getting to pitch enough.”73 Proving he could learn new tricks, Sam added a slider from teammate Frank Lary. He went 11 innings in a tough loss to Cleveland on June 26. An earlier highlight came on April 26, when he hit his only homer in the majors, off Dave Wickersham of Kansas City.

However, Sam missed most of September after hurting his leg in a car accident (he was at home in Monongah for an off-day after a series in Baltimore).74 He got the sense as the season wound down that the Tigers would release him.75 They did so, on September 28, with two games left to play.76 As a result, Jones missed out on a third straight American tour of Japan.

Bill Rigney, then managing the Los Angeles Angels, gave his former ace a chance to make his team in spring training of 1963. Sam had reached out to him when the writing was on the wall in Detroit. Much as Rig wanted to keep his old favorite, it didn’t work out. However, Jones signed “for peanuts” with Toronto, the top farm club of the Milwaukee Braves, on April 26. “We offered him what we could afford, never dreaming that he would accept such a salary,” Maple Leafs manager Bill Adair declared. “But he’s determined to prove that a lot of big league people were wrong.”77

Sam spent a couple of months with the Maple Leafs, and then the Cardinals organization obtained him in late June. They assigned him to their Atlanta Crackers affiliate. According to Detroit scout Cy Williams, “When Sam was with the Tigers last season, he was so worried [about his illness] that he lost his fastball. Now that tests have proven to him that he is in no danger, he’s a happy, carefree man and his fastball is humming. He’ll be with St. Louis before long, and he’ll do a good job for them.”78

Indeed, Sam remained an effective pitcher at the Triple-A level (9-4, 2.57 between Toronto and Atlanta), and the Cards called him up that August. In Atlanta, he also tutored young pitchers such as Harry Fanok, a Redbirds prospect with a terrific fastball but no true second pitch until Jones showed him how to get rotation on the curve. Harry remembers Sam’s favorite adult beverage (Scotch and milk on the rocks!) and also how the veteran never ran with the rest of the pitchers in practice, saying “You can’t run the ball up to the batter!” Perhaps if his mentor had still been with the Crackers, Fanok might have been able to avoid the sore arm that curtailed his career. At any rate, while Sam won both his decisions and had two saves in 11 appearances for the Cardinals, his ERA was 9.00. He was released shortly after the season ended.

It had been nine years since Jones had pitched in winter ball, but he went to the Dominican Republic in 1963-64 to play with Aguilas Cibaeñas. This club had a working agreement with the Pittsburgh Pirates, who sent the likes of Steve Blass and Bob Veale to pitch there, along with position players including Willie Stargell and Elmo Plaskett. The manager, Bucs coach Gene Baker, went way back with Sam. Baker was on the Kansas City Monarchs in 1948, but the men really became close as Gene played second base for the Cubs during Sam’s two seasons in Chicago. Ernie Banks and “Sharp Top” (as Banks called his brainy double-play partner) came to Monongah to hunt with Jones in the offseason.79 Joe Christopher, who was Baker’s teammate with Pittsburgh in 1960, remembers how the older man took him on visits to Sam’s San Francisco apartment.

Jones looked sharp in the Dominican League (4-1, 1.55). Thus the Pittsburgh organization retained the veteran in 1964, assigning him to the Columbus Jets in the International League. However, he did enjoy a last fling in the majors with the Baltimore Orioles in September of that season. The O’s were making a run at the pennant with their staff of “Baby Birds,” and manager Hank Bauer said, “I wanted someone with experience. Jones was recommended by Darrell Johnson [manager of Baltimore’s Rochester farm club], who said he has done a good job for Columbus this season.”80 Indeed, Sam had struck out 89 in 82 innings over 52 games (7-6, 1.76), and was named to the IL All-Star team. He pitched the last inning as this squad defeated the Cleveland Indians, 4-2, in an in-season exhibition game at Buffalo on August 17.

Bauer used Jones in short and long relief, and he went 0-0, 2.61 in seven games. Meanwhile, as part of the transaction that brought Jones to the Orioles, Columbus obtained the legendary erratic flamethrower Steve Dalkowski from Baltimore’s Class A team in Stockton. It was a conditional deal. According to John-William Greenbaum, who has studied Dalkowski’s career in detail, “The kicker was that Pittsburgh had to place Steve on the 40-man roster and call him up for the deal to stick. They did neither — Steve’s stats at Columbus are truly bizarre — and each man was returned to his respective organization after the season.” The Orioles released Jones on October 20, closing out his major-league career. Sam’s final marks were 102 wins and 101 losses, with a 3.59 ERA and 9 saves. He notched 1,376 strikeouts in 1,643⅓ innings, for an imposing ratio of 7.54 per 9 innings. Among his 76 complete games, Jones threw 17 shutouts.

His lifetime batting average of .149 merits a brief aside: Arthur Daley of the New York Times once told how Sam got a pinch-hit double in 1958 with his eyes closed — but the record suggests this tale is apocryphal. Jones neither pinch-hit nor doubled that year, nor did he have a base hit in the same week as the nuclear submarine Nautilus crossed beneath the North Pole, as St. Louis broadcaster Joe Garagiola allegedly quipped.

In the winter of 1964-65, Sam embarked on yet another Caribbean adventure. This time he went to Nicaragua, where a pretty fair winter league existed from 1956 through 1967. He played for the Bóer Indians, who won the league championship under Panamanian catcher-manager Calvin Byron after Whitey Kurowski left for personal reasons. Jones posted a 2-0 record with a 3.35 ERA, fanning 46 men in 45 innings.81 On the Indians staff with him was young lefthander Grant Jackson, who would start his 18-year major-league career in September 1965.

Sam closed out his professional journey with three more years in Columbus. Said Jets manager Larry Shepard in May 1965, “The only reason we have Jones is that most major-league managers have a phobia about a pitcher’s age.”82 In his own mind, the veteran felt, “No reason I can’t stay active another ten years.”83 “There’s what keeps me going,” Jones said one day that season, pointing to his two teenage sons cavorting around the field before a game in Columbus.84

On July 16, 1965, Jones was honored by the Central Ohio Home Plate Club for his relief work, receiving a truckload of gifts.85 He was a repeat member of the IL All-Star team and wound up as Pitcher of the Year (12-4, 3.04 in 77 innings over 58 games, with 22 saves). However, he was in Fairmont General Hospital when he received his award that October. He suffered badly broken ribs and lacerations in a car accident on September 16, shortly after the pennant-winning Jets had lost the Governors’ Cup finals to Toronto. On a bridge in New Martinsville, West Virginia, about an hour from home, Sam failed to yield the right of way. His new Cadillac (he always liked Caddy convertibles) bounced off the rails and rammed into the rear wheels of a tractor-trailer loaded with 30,000 pounds of plate glass. Also in the car were his wife, sister-in-law, and niece.86 After staying in the hospital for several weeks, he suffered complications — the steering wheel had caused internal injuries — and had to return for surgery.87, 88

Nonetheless, Jones remained effective with Columbus in 1966 (7-3, 2.95). He was still capable of some most impressive performances. On August 25 he fired five shutout innings in relief, retiring 15 of 16 men — 11 by strikeout. He started the ’67 season on the disabled list, but was still by no means bad (7-8, 3.95). “It’s a wonder the guy can even lob a baseball, let alone pitch as he does,” said club physician John Stephens. “Sam has an arthritic shoulder, but he just keeps rollin’ along.”89

However, his time on the mound ended at last as the Jets released him on October 14, 1967. He then returned to Monongah. Among other things, said area journalist John Veasey, Sam was responsible for bringing the first drive-through car wash to his hometown. He persuaded his former boss Tony Sauro, the dry-cleaner owner, to invest in the business. In addition, he reportedly also served as a part-time scout with the Cardinals.90

At some point — it’s not certain exactly when — Sam’s neck cancer returned and spread. He entered West Virginia University Hospital in Morgantown on June 1, 1971, and was there off and on for treatment over the next five months. In October, the news reached Johnny Bushman from San Francisco, by then a 23-year-old college student. While watching a Giants game, he heard that his old hero was gravely ill. That very night he dropped everything to fly east. Bushman said, “Sam had done so much for me when I was a boy that, in whatever small way I could, I wanted to repay him.”91

John Veasey — who knew Sam well and took several photos for Dick Schaap’s profile — spotted Johnny in the hospital. He wrote a touching story that the Associated Press then made national. It was an emotional reunion for the two men in Sam’s hospital room; both were moved to tears. Johnny planned to stay with the Jones family in Monongah “as long as they will put up with him.”92 Indeed, he was there when the end finally came on November 5. “I brought back the ball he’d given me from his 20th win in 1959,” says Bushman today. “But after Sam passed, then Mary gave it back to me again.”

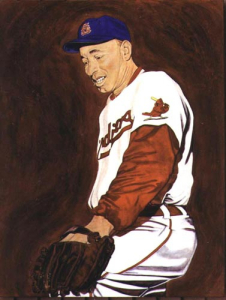

Sam Jones is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery, in Fairmont. His modest headstone bears the inscription “‘Sad’ Sam 1925-1971.” The town of Monongah erected a sign in front of Sam’s home that included a career overview. SABR member John Schwarz (who profiled the pitcher for the 2002 edition of The National Pastime) honored Sam’s memory in another most distinctive way. He commissioned artist Jennifer Ettinger of Vancouver, British Columbia, to paint a 40-by-30-inch portrait in acrylic. She may have captured the man’s expression better than any photo — down to his trademark toothpick.

Sam Jones is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery, in Fairmont. His modest headstone bears the inscription “‘Sad’ Sam 1925-1971.” The town of Monongah erected a sign in front of Sam’s home that included a career overview. SABR member John Schwarz (who profiled the pitcher for the 2002 edition of The National Pastime) honored Sam’s memory in another most distinctive way. He commissioned artist Jennifer Ettinger of Vancouver, British Columbia, to paint a 40-by-30-inch portrait in acrylic. She may have captured the man’s expression better than any photo — down to his trademark toothpick.

Quotes on Sam Jones and his stuff

“Sam had the best curveball I ever saw. . .He was quick and fast and that curve was terrific, so big it was like a change of pace. I’ve seen guys fall down on sweeping curves that became strikes. Righthanders thought Sam had the most wicked curve, and as a left-handed hitter, I thought that it was positively the best.” —Stan Musial93

“I think it’s fair to compare Jones with [Dazzy] Vance. . .He’s got that sidearm one, a flat curve that breaks away from a right-handed hitter. And he’s got that three-quarter overhand that breaks down and out. That’s what we used to call an out-drop. He changes speeds on both of them. Then, when you’re looking for the curve, he’s got that good fastball.” —Whit Wyatt94

“You’ve never seen a curveball until you’ve seen Sam Jones’ curveball. If you were a right-handed hitter, that ball started out a good four feet behind you. It took a little courage to stay in there because he was wild and he could throw a fastball very hard.” — Hobie Landrith95

“In all my years playing baseball, I’ve never struck out sitting down.” — Pee Wee Reese96

“Sam threw one of his famous benders and [Jerry] Buchek tried to duck down. But the hook followed him all the way for a called strike three! There were many giggles happening in our dugout. Overmatch city!” — Harry Fanok

“It wasn’t the curveball so much, because you could see the spin. It was the wildness, because you weren’t sure what the pitch was.” — Eddie O’Brien97

Originally published in 2008. Updated in 2012. Most recently revised on August 7, 2021, with information on Jones’ activity with the Oakland Larks.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to John Bushman, John Veasey, and Jennifer Ettinger, as well as major leaguers Valmy Thomas, Harry Fanok, and Joe Christopher, and SABR members John Schwarz, Armand Peterson, Larry Lester, Alfonso Tusa, and Herm Krabbenhoft (the last of whom provided additional research on Jones and the Oakland Larks).

Sources

Riley, James A. The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1994.

Holway, John. The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues. Fern Park, Florida: Hastings House Publishers, 2001.

Professional Baseball Players Database V6.0

Crescioni Benítez, José A. El Béisbol Profesional Boricua. San Juan, Puerto Rico: Aurora Comunicación Integral, Inc., 1997.

Gutiérrez, Daniel, Efraim Álvarez, and Daniel Gutiérrez, Jr. La Enciclopedia del Béisbol en Venezuela. Caracas, Venezuela: Editorial Norma, 2007.

www.baseball-reference.com

www.retrosheet.org

www.ancestry.com (1930 and 1940 census data)

Vital records, Belmont County (Ohio) Health Department (thank you to Jill Antolak, Deputy Registrar)

Japan-U.S.A Baseball Game History (Japanese-language special magazine, Yoshikazu Matsubayashi, editor-in-chief), 2004.

Picture Credits

The Topps Company

Jennifer Ettinger

Notes

1 Moffi, Larry, and Jonathan Kronstadt. Crossing the Line: Black Major Leaguers 1947-1959. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1994: 57.

2 Mandel, Mike. SF Giants: An Oral History. Santa Cruz, California: self-published, 1979: 70.

3 Armstead, Robert and S.L. Gardner. Black Days, Black Dust: The Memories of an African American Coal Miner. Knoxville, Tennessee: University of Tennessee Press, 2002: 56.

4 Terrell, Roy. “A Toothpick For The Pennant.” Sports Illustrated, April 11, 1960.

5 Armstead, Black Days, Black Dust: 56.

6 Schaap, Dick. “The Ups and Downs of Sad Sam.” Sport, June 1960: 57. Bob Broeg (see note 30) wrote that Charles Jones’ accident took place when Sam was 11 — an inconsistency that may also support a 1923 birthdate.

7 Ibid.: 61.

8 Armstead, Black Days, Black Dust: 56.

9 Schaap, op. cit., loc. cit.

10 Schrader, Gus. “Sam Jones Seeks Change of Luck.” Cedar Rapids Gazette, Cedar Rapids, Iowa, April 15, 1952: 13. Wells Twombly, the literary sportswriter who penned the truest Sam Jones obituary (see note 61), worked in Los Angeles in 1959. He alludes to Sam smoking cigarettes.

11 Falls, Joe. “‘I Feel Undressed Without My Toothpick’—Sam Jones.” Detroit Free Press, March 14, 1962.

12 Schaap, op. cit.: 61.

13 Terrell, op. cit.

14 Young, A.S. “Doc.” “Padres’ Sad Sam Jones Helps Keep San Diego Fans Happy.” The Sporting News, June 20, 1951: 16.

15 Figueredo, Jorge S. Béisbol Cubano: A un Paso de las Grandes Ligas, 1878-1961. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2005: 260.

16 “Negro World Series.” The Sporting News, October 1, 1947: 36-37.

17 “Important Game Thursday For Cleveland Buckeyes”. Newark Advocate and American Tribune, Newark, Ohio, July 21, 1948: 8.

18 Schaap, op. cit.: 63.

19 Lebovitz, Hal. “‘You’ll See a Lot of Sam Jones in ’52,’ Says Lopez.” The Sporting News, October 10, 1951: 29.

20 Young, A.S. “Doc.” “Convinced Doubting Scribe of Pace Change With Wins.” The Sporting News, June 20, 1951: 16.

21 “Rockets, Royals Tangle Today.” The Independent (Long Beach, California), October 2, 1948: 14.

22 “Paige Defeats Bearden,” Daily Freeman, Waukesha, Wisconsin, October 25, 1948: 9.

23 Eberenz, Leo J. “Three Teams Vie for Top in Panama Loop”. The Sporting News, February 16, 1949: 24.

24 Eberenz, Leo J. “Spur Cola in Caribbean Series as Panama Pro Loop Leader.” The Sporting News, February 23, 1949: 26, 28.

25 Eberenz, Leo J. “Spur Cola Wins Panama Pro Title From Chesterfield.” The Sporting News, March 23, 1949: 34.

26 Figueredo, Jorge S. Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2005: 315.

27 Peterson, Armand, and Tom Tomashek, Town Ball: The Glory Days of Minnesota Amateur Baseball. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006: Part III, Chapter 2.

28 Ibid., Part I, Chapter 4.

29 Schaap, op. cit.: 63.

30 Eberenz, Leo J. “Biscan Busy With Brush in Panama Winter Loop.” The Sporting News, January 18, 1950: 20.

31 Lacy, Sam. “Girls Behind the Guys.” Baltimore Afro-American, May 13, 1952.

32 “Honor Chakales in Eastern Loop”. Charleston Daily Mail, Charleston, West Virginia, November 10, 1950: 21.

33 Schaap, op. cit.: 63.

34 Broeg, Bob. “Jones Turns Into Winner as Control Pitcher.” The Sporting News, August 20, 1958: 5.

35 Eberenz, Leo J. “Carta Vieja Has Trouble Lining Up Manager, Players.” The Sporting News, November 8, 1950: 22.

36 Eberenz, Leo J. “Grodzicki to Manage in Canal Loop.” The Sporting News, November 22, 1950: 20.

37 Delano, Fred. “San Diego Mound Staff Coast’s Best?” Press-Telegram, Long Beach, California, March 31, 1951: B3.

38 Schaap, op. cit.: 60.

39 Young, A.S. “Doc.” “Padres’ Sad Sam Jones Helps Keep San Diego Fans Happy.”

40 Schaap, op. cit.: 63.

41 Schaap, op. cit.: 62-63.

42 Young, “Padres’ Sad Sam Jones Helps Keep San Diego Fans Happy.”

43 “Special Days.” The Sporting News, August 29, 1951: 15.

44 “Tigers Spoil Tribe Exit, 2-1, Sunday.” Lima News, Lima, Ohio, October 1, 1951: 14.

45 Lebovitz, op. cit.

46 Van Hyning, Thomas E. The Santurce Crabbers. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1999: 47-48.

47 Schaap, op. cit.: 63.

48 Schrader, loc. cit.

49 Lang, Jack. “Indians Sign Agreement With Club in Venezuela.” The Sporting News, September 23, 1953: 32.

50 “Weik Only Indian To Play This Winter”. East Liverpool Review, East Liverpool, Ohio, October 9, 1952: 14.

51 Peterson and Tomashek, op cit., Part III, Chapter 2.

52 Van Hyning, Thomas E. Puerto Rico’s Winter League. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1995: 216.

53 Schaap, op. cit.: 60.

54 Van Hyning, The Santurce Crabbers: 70-71.

55 Liska, Jerry. “Another Walk Would Have Yanked Jones From No-Hitter”. The News-Palladium (Benton Harbor, Michigan), May 13, 1955: 16.

56 Reynolds, Speck. “Speck Speculates,” Daily Tribune, Great Bend, Kansas, June 12, 1955: 10.

57 Moffi and Kronstadt, op. cit.: 58.

58 Schaap, op. cit.: 65.

59 Daley, Arthur. “Man Who Chews Toothpicks,” New York Times, September 14, 1958: S2.

60 Broeg, op. cit.

61 “Obituaries”. The Sporting News, November 20, 1971: 54. (See also Schaap, op. cit.: 59).

62 “Sad Sam Brings Joy to San Francisco Club”. Lincoln Journal, Lincoln, Nebraska, March 26, 1959: 17.

63 Moffi and Kronstadt, op. cit., loc. cit.

64 Schaap, op. cit.: 59.

65 Twombly, Wells. “Sam Jones and His Loyal Rooter.” The Sporting News, November 13, 1971: 47.

66 “Sam Jones Back Home for Winter.” Raleigh Register (Beckley, West Virginia), November 6, 1959: 9.

67 Schaap, op. cit.: 65.

68 “Sad Sam’s Visit to Hospital Brightens Up Polio Victim.” The Sporting News, April 27, 1960: 10.

69 “Giants Sold Me Down River, Claims Sam Jones”. Oakland Tribune, October 11, 1961: 39.

70 “Detroit Adds Sam Jones to Pitching Staff.” Monitor-Index, Moberly, Missouri, December 2, 1961: 6.

71 Newhan, Ross. “Sad Sam Fans Life’s Deadliest Hitter”. Long Beach Independent-Press-Telegram, February 17, 1963: D2.

72 “Tiger Hurler Benched by Neck Growth.” Arizona Daily Sun, Flagstaff, Arizona, March 21, 1962: 8.

73 Spoelstra, Watson. “Tigers Flash Toothy Grin for Sad Sam’s New Secret Weapon.” The Sporting News, July 14, 1962: 11.

74 “Tigers Pitcher in Auto Wreck.” Daily Mail, Charleston, West Virginia, September 8, 1962: 8.

75 Newhan, op. cit.

76 “Tigers Free Sam Jones.” Titusville Herald, Titusville, Pennsylvania, September 29, 1962: 8.

77 “Sad Sam on Comeback Trail.” The Sporting News, June 1, 1963: 38.

78 Reddy, Bill. “Keeping Posted.” Syracuse Post-Standard, July 9, 1963: 17.

79 Hardman, A.L. “Sam Glad Not to Face Stan Any More.” The Sporting News, December 19, 1956: 10.

80 “Birds Add Sam Jones for AL Stretch Drive.” Frederick Post, Frederick, Maryland, September 1, 1964: 9.

81 The Sporting News, February 6, 1965: 24.

82 Kritzer, Cy. “Sam Jones to Lead Pennant Push by Jets, Shepard Says.” The Sporting News, May 1, 1965: 35.

83 “Sad Sam Top Int. Reliever.” El Paso Herald-Post, June 17, 1965: 31.

84 Fisher, Eddie. “Toothpick Sam, Hefty Herrera Help Jets Shoot Down Int Foes.” The Sporting News, July 3, 1965: 31.

85 “Jets Fans Honor Sam Jones, Crax Hurler Upstages Him.” The Sporting News, July 31, 1965: 31.

86 “Baseball Pitcher Hurt in Accident”. Beckley Post-Herald, Beckley, West Virginia, September 17, 1965: 1.

87 “Sam Jones of Jets Named Int. Loop’s No. 1 Pitcher,” The Sporting News, October 16, 1965.

88 Kritzer, Cy. “Jets, Braves, Leafs, Tabbed Top Dogs in Chase For Int Flag.” The Sporting News, April 23, 1966: 27.

89 “Sam Jones Rolls On.” The Sporting News, June 10, 1967: 41.

90 Hager, Don. “Too Many Stars. . .So Award Dropped!” Daily Mail, Charleston, West Virginia, May 10, 1969: 7.

91 Veasey, John. “Now Johnny Visits Sad Sam.” Charleston Daily Mail, October 7, 1971: 30.

92 Ibid.

93 Musial, Stan and Broeg, Bob. Stan Musial: “The Man’s” Own Story. New York: Doubleday, 1964.

94 Moffi and Kronstadt, op. cit.: 57.

95 Schaap, op. cit.: 59.

96 Mandel, op. cit.

97 Neyer, Rob and James, Bill. The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004: 261.

Full Name

Samuel Jones (name at birth: Daniel Pore Franklin)

Born

December 14, 1925 at Stewartsville, OH (USA)

Died

November 5, 1971 at Morgantown, WV (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.