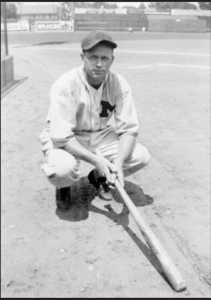

Chet Morgan

Chick Morgan could have boasted of playing in the major leagues with the Detroit Tigers, or of a 17-year career spanning three decades as a professional player. Yet, somehow, it seems quite plausible that his greatest satisfaction could have been that 80 years after he began his first season in the minors, his great grandson is carrying on a love for the game with the same passion Morgan showed when playing.

Chick Morgan could have boasted of playing in the major leagues with the Detroit Tigers, or of a 17-year career spanning three decades as a professional player. Yet, somehow, it seems quite plausible that his greatest satisfaction could have been that 80 years after he began his first season in the minors, his great grandson is carrying on a love for the game with the same passion Morgan showed when playing.

Chester Collins Morgan was born on June 6, 1910 in Skene, Bolivar County, Mississippi to Isaac Daniel, a farmer, and Jessie Inez Morgan.1 Chester was the third of eight children in the Morgan household. Growing up on his father’s farm, Chester graduated from the local high school and played town ball, often with or against older men. Eventually the region became aware of his talent. After acquitting himself well at a tournament in Memphis, Tennessee, he was offered a contract with the Southern Association Memphis Chickasaws (Chicks) in 1931. Before playing a game with Memphis however, Vicksburg of the Cotton States League picked up his contract —and promptly dropped him.2 While he did not play professional ball in 1931, he did gain a nickname, Chick, bestowed on him for his ever so brief association with Memphis.3

That year proved to be important to Morgan for a far more permanent association, as he married his high school sweetheart, Audrey Hattie Howard. They met while he was in the sixth grade, Hattie in the fourth. Their marriage lasted until Morgan passed away in 1991. They had two children, Chester Collins Morgan Jr., born in 1932, and Danny Lee Morgan, born in 1943.

The Texas League Beaumont Exporters signed Morgan to a contract in the fall of 1932. Morgan’s son recalled years later that his father’s joining the club in the spring of 1933 was not exactly auspicious. Former major-league player Bob Coleman was then managing Beaumont. When meeting young Morgan, Coleman asked where his bats were. Morgan had none; he assumed the team supplied them. Exasperated with the naiveté of the rookie, Coleman gave Morgan $10 and told him to buy a bat at the local general store. Morgan promptly went into town and bought a Hanna Batrite model bat.4 His store-bought bat served him so well, that he continued using Hanna Batrites most of his career. Playing on a team with the likes of Elden Auker, Claude Passeau, and Rudy York, Morgan played solid defense at third and hit a creditable .294 for the Detroit Tigers-affiliated club.

In 1934, Morgan started with Beaumont, but when the San Antonio Missions’ third baseman Harland Clift was called up to play with the major-league St. Louis Browns, Morgan was transferred to the Missions. He went on to have a great year for San Antonio, capturing the batting title with a .342 mark. Morgan led the league with 216 hits, scored 120 runs, hit 42 doubles, legged out ten triples and made six home runs.5 Using a split-hand batting grip along the lines of Ty Cobb, Morgan developed superb bat control, producing line drives rather than generating power. During the season, Morgan shifted from third to the outfield to capitalize on his speed. For the rest of his career, he played the outfield.

In describing his capture of the batting title, The Sporting News noted Morgan was born on June 6, 1913, three years after his actual birth, reflecting a practice among players of his era to enhance one’s potential by reporting a younger birth date. The article further went on to say the Philadelphia Phillies had drafted Morgan, who would report to their camp the following spring. 6

Although having played for San Antonio, affiliated with the Browns, Morgan still belonged to Beaumont, a Tigers affiliate. After the season ended, an announcement was made that Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Landis was investigating whether Morgan’s playing time in the minors was sufficient in duration to be eligible for the draft.7 It evidently was not, as a few months later Detroit purchased Morgan’s services from Beaumont.8 This was not the last time Morgan came to the attention of Landis.

The Tigers were coming off a pennant-winning effort the year before. Morgan faced tough competition in making the club, let alone becoming a starter. Pete Fox, Goose Goslin, and Jo-Jo White had performed well in 1934, ably backed up by reserve outfielder Gee Walker. Morgan’s ability to make the club received a boost because of Detroit manager Mickey Cochrane’s perception that the club was not hustling, that they lacked “pep.” At one point, Cochrane lashed into his players, accusing them of loafing and warning them they could not repeat their league championship if they failed to hustle. One way to do so was to let some of the regulars know they had not cinched a starting position. This worked to Morgan’s advantage, as he did well in spring training, impressing all with his hitting, at one point going 12-for-25 during practice games.9 Cochrane, a keen judge of baseball talent, was impressed by Morgan’s hitting —not as much with his fielding. Cochrane was probably correct in that assessment. At this point in his career, Morgan had played just half a season in the outfield.

His performance allowed him to make the team after just two seasons in the minors. Detroit, as Cochrane feared, was not ready as the season began. They got off to a slow start, languishing in the second division much of the early going. Morgan made his first appearance in the third game of the season, on April 19, pinch-hitting unsuccessfully for pitcher Firpo Marberry in the bottom of the ninth in a losing effort against the White Sox. The next day, Cochrane decided to shake up the lineup, putting Morgan in left field, batting eighth, getting the nod over Pete Fox and Gee Walker. Morgan played the next several games —then disaster struck.

When asked why his father’s major-league career was so brief despite having played well in the high minors, Chester Jr.’s response was quick, “He always told me his career was hurt because he dropped a fly ball.” Morgan had been in the starting lineup for less than a week when he made his miscue against Chicago, in a scoreless game, the bases loaded and two out. Two runs scored on the play; three more came in before the Tigers got out of the inning. They eventually lost 7-2.10 Cochrane replaced Morgan with Pete Fox in the lineup the next day. It was Morgan’s last game in the field that year, his opportunity to crack the lineup now lost.

Over the next several weeks, he pinch-hit occasionally, going just 1-for-8. During the first week of June, not hitting, his defense suspect, Detroit optioned Morgan to the Toledo Mud Hens. When the Tigers optioned Morgan they had just started to turn things around. They would catch the Yankees in late July, going on to win their second straight pennant and beat the Chicago Cubs in the World Series. Meanwhile Morgan finished out the season with Toledo, appearing in 107 games for the American Association’s Mud Hens, while batting .321.

That error would haunt his career over the intervening years. The next season Morgan went to the Tigers’ spring training camp. During camp, Cochrane was interviewed about the crop of rookies seeking to make the club. He spoke highly of the likes of Gil English, Chet Laabs, and Rudy York. Cochrane’s take on Morgan however, went along the lines of, “Chester Morgan can hit, but his fielding is not so good.” 11

When camp broke, Morgan went to the Milwaukee Brewers, also in the American Association, Milwaukee having succeeded Toledo as a Tigers affiliate. For the year, Morgan hit .297 as Milwaukee captured the Junior World Series against the Buffalo Bisons. Each player on the winning Brewers club received $648 —a far cry from the New York Yankees players’ World Series winning shares of $6,430 for their victory over the Giants.12 While Morgan’s winnings might have seemed meager when compared to the Yankees, he put it to good use for his farming activities in Bolivar County. An article about offseason activities noted Morgan was working property “clearing out some cut-over land.”13 Morgan was intent on getting his own property.

Toledo reestablished its affiliation with Detroit for the 1937 season and Morgan went back to the Mud Hens. He hit 22 doubles, 10 triples, and just 3 home runs while batting .308. It seemed as if he was never destined to make it back to the big leagues. Morgan again started the 1938 season with Toledo and went on a tear. By early July, he was leading the league in batting with a .361 average. At the same time, Detroit was playing poorly thanks to a combination of inadequate pitching, injuries, and a general fall-off in performance from several players. After having won the World Series in 1935, they had followed up with two consecutive second place finishes, but by July 10, were in fifth place. Jo-Jo White had hurt his ankle, and center-fielder Chet Laabs, mired in a 2-for-26 slump, was not helping the club. Shaking up the team, Detroit traded Laabs to Toledo for Morgan. Morgan immediately began playing center field and batting leadoff for the Tigers. It was noted that he “brought assurances of defensive improvement since his last trial with the Tigers.”14 When contacted by the Toledo News-Bee on July 11, Mrs. Morgan was near ecstasy. “Oh boy am I happy. Is Chester happy? You bet. He’s like me. He called me this morning and was plenty excited. I nearly fainted when he struck out his first time at bat yesterday.” That Morgan made a fine catch and made two hits, alleviated her concern.15

Morgan started every game until mid September. That he played center field, a demanding defensive position, reflected how well his fielding had improved since his inauspicious debut in 1935. Detroit continued to play poorly, however. On August 6, with Morgan hitting .340 and the Tigers having lost their fourth straight game, coach Del Baker took over for Cochrane, who resigned. The team immediately started to play better under Baker’s low-key style of management. Under his guidance, they went 37-19 the rest of the way to finish in fourth place, 16 games behind the Yankees. Morgan continued to hit over .300 until mid-September, a late-season slump brought him down to .284. On September 29, he went 0-for-5 against the Browns. It was his last major-league game. Ominously for Morgan, Chet Laabs, recalled from the minors, played the last three games of the season.

At first glance, Morgan’s .284 average seems respectable enough by today’s standards. Placed within the context of the times, however, his performance is lessened by the realization the American League’s overall batting average was .281. With just six doubles, one triple, and no home runs, Morgan’s line-drive hitting ability generated little power, a sought-after commodity for outfielders. While today’s on-base plus slugging (OPS) average calculations were not used in 1938, Morgan’s virtually powerless .641 was over 80 points behind the next-lowest of outfield regulars in the American League that year.16

His ability to stay in the majors received a fatal blow on December 15, 1938, when he, Elden Auker, and Jake Wade were traded to the Red Sox for third baseman Pinky Higgins and Archie McKain. Morgan joined a Sox outfield comprised of Doc Cramer and Joe Vosmik both proven career .300 hitters. The third outfielder was a rookie from the Sox’s minor league Minneapolis Millers team —Ted Williams. It was a hopeless situation for Morgan. Morgan was sent to the Louisville Colonels in the American Association, where he became a fixture for several years, never again a serious prospect for the majors.

The Colonels were one rung below the majors, over 80% of their roster comprised of players who had or would play in the majors. Playing excellent ball, they made the Junior World Series in 1939-40, winning the series in 1939.17 Morgan’s teammates included the likes of Johnny Pesky, Pee Wee Reese, and Stan Spence. His play was solid, averaging 150 games per year through 1942, “one of the best defensive gardeners in the circuit,” as described in The Sporting News.18

While not getting back to the majors, he did experience a bit of good fortune.

Commissioner Landis had always looked with a jaundiced eye at the relationship between the major and minor leagues. Several times during his tenure, Landis freed minor leaguers from their contracts when it became apparent that various major-league teams were not treating them correctly, that they were in essence controlling their services through interlocking (and often secret) arrangements between major-league clubs and their minor-league affiliates. Landis was also concerned when major-league teams to all intents and purposes controlled several teams in one league. His particular nemesis was Branch Rickey of the St. Louis Cardinals. In 1938, Landis freed 91 players from their contracts with the Cardinals.

Two years later Landis took similar action against the Tigers, whose practices in controlling their players was similar in many ways to Rickey’s operations. Detroit also lost 91 players. Landis’s decision went beyond those players still controlled by Detroit; he declared that those no longer with the Tiger’s organization, but who had previously been held under contracts illegally, should be compensated. One of these was Morgan, formerly property of the Tigers but now under auspices of the Red Sox. Landis ordered Morgan be paid $5,000 by Detroit. 19

This action allowed Morgan to purchase what eventually became a 360-acre cotton farm near Boyle, Mississippi. Near the Mississippi River, on land extremely fertile, it was a superior property for raising cotton. Chet Jr., growing up there, recalled catfish ponds, exploring the surrounding woods and hunting for rabbit with his father, a crack shot with a .22.20 Farming was a prominent part of Morgan’s life; his work at Boyle was often noted in articles about player offseason activities.21

At the start of the 1943 season, Morgan announced his retirement from baseball to focus on farming. Married, the father of two boys, he was exempt from the draft, assigned a 3-A status, a deferment granted because of hardship to dependents.22 Somewhat into the season, Morgan reversed his decision and rejoined the Colonels.23 Subsequently he suffered an attack of appendicitis, keeping him off the field for several weeks.24 Playing just 56 games, Morgan hit .235. After the season ended, he was traded to the Buffalo Bisons and then the Toronto Maple Leafs where he stayed until 1946. Briefly playing with the Tulsa Oilers of the Texas League that year, he decided to retire again, a decision keeping him out of baseball in 1947.

In 1948, Morgan came out of retirement as playing manager for the Clarksdale Planters in the Cotton States League, a Class C League that had been in existence off and on since 1902. The Planters, like most teams in the league, were unaffiliated with any major-league club. They played in Clarksdale’s Community Park approximately 50 miles from Morgan’s farm. The league was part of a post-World War II boom where minor leagues flourished.

In Morgan’s first season as manager, the team did well, finishing second to the Brooklyn-affiliated Greenwood Dodgers. Morgan hit .314, tied for third in the league of players having at least 400 at-bats.

In 1949, Morgan was one of two managers for a Planters team that finished seventh; in 1950, he managed the entire season. By then he was not only playing and managing but also serving as general manager and part owner.25 For the year, Morgan batted .327 in 96 games as the Planters again finished seventh. It was his final year as a player. His career ended as it had begun, playing for a local team.

Morgan’s major-league record covered a little more than half a season’s worth of games, hitting .277 in 88 games. His minor-league record was impressive. Over the course of 17 seasons, he appeared in nearly 1,900 games, making 2,142 hits and finishing with a lifetime average of .302.

He remained affiliated with the Planters who shifted to Greenville in 1953 when he briefly came back to manage, only to resign late in the season.26 By then the Morgan family focus in baseball was on his son, Chester Collins Morgan Jr. who had signed with the Boston Braves organization.

Chester Jr. – “Thumper” as he came to be known – played seven years in the minors. He began in 1950, his father’s last year of play, one of just a few times father and son played professional ball simultaneously. In 1951, Chester Jr. was assigned to the Evansville Braves of the Three-I League. His manager, Bob Coleman, had managed Chet Sr. years before.27 Morgan Jr. played through 1956. Along the way Chet Jr. played ball with the likes of future major-leaguers Don McMahon, Wes Covington, and, in 1952-1953, Hank Aaron.

After Chet Sr. severed his relations with Greenville, drought-like conditions forced him to sell his farm. In 1954, he and Audrey moved to Pasadena, Texas, where brother Laburn still resided. Morgan joined the city’s water department, eventually becoming superintendent, and played fast pitch softball in the local church league. After retiring, he worked as a security officer before passing away on September 20, 1991 from congestive heart failure at the age of 81. Audrey, Chester Jr., Danny, along with three grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren, survived him.28

After Chet Jr.’s playing career ended, he taught at the high school level and coached baseball. He was recruited to coach baseball in Italy where he and wife Shirley lived several years, reveling in the experience. Chet Jr. managed Olympic level players, several times taking teams to European and World Championship level playoffs.29

One of the continuing themes of baseball is a love for the game passing from generation to generation. Chet Jr.’s son Mitchell, coached Little League ball and his grandson, M. Jacob Samuel Morgan is playing ball practically year round in the El Paso area and various regional tournaments. A switch-hitter, the 17-year-old plays infield and is trying his hand at pitching. Chet Sr. would be proud, and, if asked, might advise young Morgan to think about batting with hands slightly apart because, “you get a little bit better bat control that way.”

Notes

1 Some baseball reference sources showed Morgan’s birthplace as nearby Cleveland, Mississippi. Morgan’s son Chester Collins Morgan Jr. advised in a phone interview on July 22, 2013 that his father was born in Skene, Mississippi. A profile of Morgan in The Sporting News on June 21, 1934, “Minors Worth Watching,” also notes Morgan’s birthplace as Skene.

2 “Minors Worth Watching,” The Sporting News, June 21, 1934, 3.

3 Interviews with Chet Morgan Jr., on July 11 and September 26-27, 2013.

4 Hanna Batrite baseball bats were manufactured in Athens, GA from the early 1900’s until the mid-1970’s, originally made out of Southern white ash. Innovations Hanna Batrite introduced included a nonchipping treatment, a “hold fast” grip for players who had a tendency toward excessive perspiration and a cork grip. http://www.stevetheump.com/Bat_History.htm

5 All statistics for this article come from either Baseball-reference.com or Retrosheet.org.

6 “Texas Batting Title to Morgan By Two-point Margin Over Hooks,” The Sporting News, November 1, 1934, 8.

7 “Reds Draft Herrmann,” Emporia Gazette, October 3, 1934, 10.

8 “Detroit Takes Chester Morgan,” San Antonio Express, January 4, 1935, 7.

9 “Cochrane Jacks Up His Pepless Tigers,” The Sporting News, March 28, 1935, 6.

10 “Chisox 7, Tigers 2,” Hartford Courant, April 24, 1935, 14.

11 “Tiger Rookies Praised By Manager Cochrane,” The Herald-Star, Steubenville, OH, April 4, 1936, p11.

12 “Brewers Win Their First Junior Series,” The Sporting News, October 8, 1936, 7 and The 1960 Baseball Guide published by The Sporting News, 135.

13 “Between Innings,” The Sporting News, December 17, 1936, 10.

14 “Cochrane Re-Sods Part of His Garden,” The Sporting News, July 14, 1938, 14.

15 “The Morgan’s Are Really Happy,” The Toledo News-Bee, July 11, 1938, 8.

16 Boston’s Doc Cramer had the next-lowest OPS at .734.

17 Called the Little World Series until 1932, the postseason series was played between two of the three top minor leagues.

18 “Most of AA Colonels Carry 3-A U.S. Listing,” The Sporting News, February 18, 1943, 10

19 “Landis Lays Down Law for Farms, Working Agreements; Detroit Loses Title to 91 Players, Must Pay 15 Others,” The Sporting News, January 1, 1940, 1.

20 Phone interview, Chet Morgan Jr. on July 11, 2013.

21 “Burwell Does Kipling As Colonels Check In,” The Sporting News, April 8, 1943, 5.

22 “Most of AA Colonels Carry 3-A U.S. Listing,” The Sporting News, February 18, 1943, 10

23 “Colonels Brightened At Short By Albright,” The Sporting News, June 24, 1943, 2.

24 “Caught On The Fly,” The Sporting News, December 12, 1943, 12.

25 “Caught On The Fly,” The Sporting News, February 1, 1950, 27.

26 “Parade of Pilots,” The Sporting News, August 5, 1953, 37.

27 “Highlights of Lower Minors,” The Sporting News, May 23, 1951, 36.

28 “Obituaries,” Pasadena Citizen, September 22, 1991, 3A.

Full Name

Chester Collins Morgan

Born

June 6, 1910 at Skene, MS (USA)

Died

September 20, 1991 at Pasadena, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.