Flame Delhi

Young Lee Delhi attended Santa Monica (California) High School and pitched for its baseball team 1908-10. As a pitcher for Santa Monica, he was known as Turk, Red and Demon Delhi.

Young Lee Delhi attended Santa Monica (California) High School and pitched for its baseball team 1908-10. As a pitcher for Santa Monica, he was known as Turk, Red and Demon Delhi.

By 1909 Delhi had began to draw attention from the Pacific Coast League. Happy Hogan, the manager of Vernon, wanted to sign the young right-hander, but Delhi declared that he “harbored no ambition to enter the game professionally — at least for several years yet.” At just 16 years of age, Delhi was already tipping the scales at 180 pounds and was reported to be “heaviest hurler in the high school ranks.” In one contest against Polytechnic at the Santa Monica baseball grounds at Tenth and Utah streets, Delhi entered the game in the second inning with his club already behind 4-0. Over the next eight innings, Delhi gave up only four hits and struck out 13 batters although Santa Monica still lost the game 6-4. “Turk” was considered the fastest thrower in the Los Angeles County Baseball League. Santa Monica coach George Morgan promised that his club would contend for the title against two-time defending champion Compton. Although Delhi starred, he could not make up for a weak-hitting lineup as his team failed to live up to expectations.

That spring the big redhead played in the Bankers League for Merchants National, often pulling double duty and pitching for Santa Monica High School one day and the Merchants the next. In the high school team photo for 1909, Delhi is wearing his Merchants uniform, suggesting that he may have had a game with the bankers that day. Of course, his cover was that he was a bank teller, but at only 16 years old it is doubtful that he actually worked at the bank while attending school at the same time. He did his work for the bank on the mound, leading his club to the league title. A Santa Monica newspaper reported, “Turk Delhi, slabster of the Merchants, is the biggest man in the league, the other players looking like Lilliputians when lined up beside him.” Following the season the league passed a rule that prohibited anyone from playing with a team who was not a bona fide employee of the institution, which the team represented. Two exceptions were made to this rule: Lee Delhi and James Rheinhard, an outfielder for the German-Americans. The rule wouldn’t matter to Delhi. He had other plans.

On October 16, 1909, still one month away from his 17th birthday and pitching as an amateur, Lee took the mound for the Los Angeles Angels against the Sacramento Sacts of the Pacific Coast League. The youngster allowed 12 hits, walked two and struck out seven in a complete game 6-5 loss.

Baseball had come to the West Coast in the 1850s as migrating easterners swarmed to California during the gold rush days. It wasn’t long before organized leagues formed in the Golden State. The California League and the Cal State League were two of the first. In 1903 the Pacific Coast League was established and soon was playing a top caliber of baseball. Because of the mild California weather, the PCL played a schedule that at times reached 225 games and lasted from March to November. This made it attractive to players who could earn a living by playing ball for about eight months out of the year. Along with the mild weather and long schedule, favorable travel conditions made the PCL one of the favorite leagues of players of the time — so much so in fact, that some players preferred playing in the Coast League to the major leagues. After the San Francisco earthquake of 1906 jeopardized the existence of the league, the PCL dwindled to just four teams for the 1907-08 seasons. Major League Baseball however, saw the value of having a West Coast training ground and helped the league get through the crisis. The National League kicked in with a $1,000 contribution while the American League, on April 29, 1906, only 11 days after the earthquake, played an exhibition game in New York between the Highlanders and the Philadelphia Athletics that raised $6,000 in relief funds. By the start of the 1909 season, the league returned to a six-team circuit with the addition of Sacramento and Vernon, a Los Angeles suburb, to holdovers Los Angeles, San Francisco, Oakland and Portland. Los Angeles, the 1908 champ, slipped to third with a 118-97 record as San Francisco won the 1909 title with a 132-80 mark.

The trial start with the Angels in 1909 led their manager, Pop Dillon, to offer Delhi a contract. Although he certainly had professional aspirations, Delhi put off any decision but promised to give Dillon “…first call on his services when he decides to enter professional baseball.” Big “Turk” then spent the winter playing for the Tufts-Lyon club where he, of course, was the star pitcher. When the 1910 high school baseball season rolled around, Delhi was already working out with the Angels and was declared ineligible to pitch the Santa Monica opener against Harvard Military School because he had entered school too late that year.

While he wasn’t allowed to start the season for Santa Monica, nothing could stop him from playing in exhibition games with the Angels. On March 18 he took the mound against the Chicago White Sox, who were training on the coast. The Sox played their regular lineup, including first baseman Chick Gandil, who would go on to be the ringleader of the infamous 1919 Black Sox, and future Hall of Fame pitcher Big Ed Walsh. Delhi started the game and pitched seven innings, gave up six hits, struck out three and didn’t walk a batter. He left with the Angels leading 2-1. But the Chisox tied the game with a run in the ninth and then scored four runs off Bull Thorsen in the tenth and went on to win 6-2. Eight days later, Delhi again faced the White Sox in Los Angeles, this time giving up five runs on seven hits in four innings and losing a 11-9 slugfest in chilly weather.

Lee returned to school to earn his diploma and was allowed to pitch for the team. He led his prep squad to the league pennant although they lost in the tournament to Los Angeles High School by a 2-1 score. During this time Delhi pitched some weekend home games for the Angels and joined the club for good after the school year ended. He was now a full-fledged professional. The Los Angeles Examiner reported his signing like this: “Delhi is the only recruit from the semi-pro ranks to stick with the Seraphs this season. He has good smoke as it is but will have clouds of it when he learns the knack of putting more of that poundage behind the ball.”

Pitching was king in 1910, smack in the middle of the Deadball Era. Portland, the league champion, hit only .218 as a team and San Francisco led the PCL with a .226 average. Hunky Shaw of San Francisco won the batting title with a .281 mark. Portland put together an amazing streak of pitching 88 consecutive scoreless innings October 6-16. Forty-eight of those innings were against the Angels; Delhi did not escape the streak as Vean Gregg twirled one of his league record 14 shutouts against the youngster. Each side finished the game with two hits but Portland came out on top 1-0. The next day’s newspaper reported “Delhi made the Portland batters look decidedly foolish by feeding them a tantalizing slow curve which they could not touch.”

When Delhi made the trip to San Francisco for a series against the Seals, it was the first time he had been away from the Los Angeles area since moving there from his Harqua Hala, Arizona, birthplace. Coming over on the boat with the other Angels players, young Delhi got chummy with fellow pitcher Bull Thorsen. It wasn’t long after the two had been chatting that some other players from the team noticed Delhi running from port to starboard like “a loco pony.” It seems that the green pitcher was looking for the boat’s bowling alley that Thorsen had assured him was on all of the boats. Now we know where Thorsen got his nickname! The Seals beat Delhi in his first appearance on a San Francisco diamond by a 5-0 score. Later, “Red” pitched a shutout of his own against the Seals, winning 4-0. He also beat them 4-1 in a September series. In that game he struck out Seals slugger Ping “Home Run” Bodie twice and “…tied him into several different brands of knots.” Delhi hit one of his two home runs for the season in the contest. He soon discovered the nightlife of San Francisco at the ripe age of 17. Delhi and his teammates would visit the nightspots and shoot BBs out of straws at the chorus girls from the front row. It was an education both on and off of the diamond for the youngster. On November 6, the final day of the 1910 season and one day after his 18th birthday, Delhi shut out Sacramento 4-0. His first season as a professional yielded a decent record of nine wins and ten losses in 25 games. He walked 38 and struck out 87. He also came away from the season with a new nickname, “Flame.” Los Angeles sportswriter Beanie Walker tagged him with the moniker. The nickname was derived as much from Lee’s stunning shock of red hair as from his blazing fastball.

Immediately after the season, Flame was signed by Kitty Brashear to play for the Doyle’s of the California Winter League. The league included teams from Los Angeles (Brashear’s team), Vernon, San Diego and the biggest drawing card of the league, the Rube Foster’s Negro Leagues Leland Giants. It was around this time that he started dating Rose Leonette of Los Angeles. Lee and Rose met at a party and, according to their daughter, “she didn’t much like him at first. She thought his red hair and big hands we re ugly.” Lee was persistent, however, and the two began a courtship that would result in their marriage in September of 1911. The couple lied about their ages on their marriage license. He said he was 22 and she said she was 18. They were really just 18 and 16, respectively.

The Angels played their games at Washington Park, also known as Chutes Park. It would be the home for Flame Delhi’s greatest season in baseball. The 1910 team had finished just 101-121, their first losing season after seven straight years of over-.500 ball, including four league titles. By 1911 baseball had arrived on the coast as the national pastime. More than 9,000 fans showed up for opening day in San Francisco while the Angels drew an overflow crowd of 7,100 to their newly remodeled ballpark. Big Red Delhi got the honor of starting the opener for the Seraphs against the defending PCL champion Portland Beavers. As was the custom, the lone umpire, Gene McGreevy, walked to the center of the diamond, cap in hand, and yelled the names of the starting batteries to the fans. Portland pitcher Tommy Seaton matched Delhi pitch for pitch through five innings. In the sixth, the champs broke through for a run against the Angels’ big right-hander. The Angels mounted a rally, scoring two runs in the seventh and chasing Seaton from the game. They added four more in the ninth and gave Delhi the cushion he needed to hang on and win the game 6-4 in spite of a three-run Beaver ninth.

Four days later, Delhi again went to the mound against Portland. With his future wife in the stands, he shut out the Beavers 1-0 allowing just one hit, a two-out single by William Rapps in the second inning. On April 22, in front of the largest crowd ever in Portland, Delhi again beat Seaton and the Beavers, this time by a 4-2 score.

Earlier in the month, on April 6, ‘The Human Sunflower’ as one scribe called Delhi, pitched two games for the price of one when he went the distance in an 18-inning marathon against the Oaks. Oakland fans had started what would become a long day by attending a luncheon with the players followed by an automobile parade to the ballpark as part of the festivities for their home opener. Oakland scored two in the first but Los Angeles caught the Oaks with one in the sixth and another in the seventh. On and on they went with Delhi and Oakland hurler Knight matching each other inning after inning. Finally, as darkness approached, the Angels pushed across a run in the top of the 18th and Delhi held the lead in the bottom half of the inning for a 3-2 win. Delhi almost caused his team to miss a chance to win when he was called out for missing second base in the last inning. Fortunately, the next hitter singled home what proved to be the winning run. Although they played double the usual number of innings, the time of game was still only 3 hours and 15 minutes. Flame’s sister, who lived in the Oakland area, was in the stands to see the big redhead’s iron-man performance.

As the season went on, Delhi kept winning and pitching well while the Angels dropped to the cellar early and stayed there all season. The Los Angeles Herald acknowledged that Delhi was about the only bright spot in the Angels’ otherwise dismal season: “When Delhi pitches Los Angeles is always conceded a chance against any team in the league, but when any of the others work the fans are generally ready to concede the victory to the opposing faction.” Indeed, by the end of the season Delhi had won 27 of the club’s 82 victories. The Angels finished dead last with 127 losses.

Meanwhile, Flame was drawing attention from the big leagues. Cincinnati had first rights to the hurler and it appeared certain that he would be there in 1912. Reds manager Clark Griffith had started negotiations with Los Angeles in January to obtain the rights to Delhi, and Cincinnati president Garry Herrmann came to the coast to watch Delhi pitch in May. Under the rules of the time, Delhi’s contract had to be sold by the October draft period or any team could draft Delhi and pay a fraction of the price that the sale of his contract would bring. Delhi started the Sunday game against Vernon with Herrmann in attendance but lost the contest due to errors behind him and the nervousness of knowing that the Cincinnati president was in the stands. The Reds hesitated in buying Delhi’s contract and other teams would soon join the bidding.

On July 19, Delhi was the victim of one of the strangest plays in baseball history. In the sixth inning of a tie game, the Angels put two men on base with no outs when Charles Moore was hit by a pitch and George Metzger walked. Vernon pitcher Al Carson was replaced by Harry Stewart, who came in to pitch to Angels third baseman Roy Akin. With the runners going, Akin hit a liner over second baseman Kitty Brasher’s head. The apparent single was headed for the outfield when center fielder Walter Carlisle came racing in and diving to the turf, he did a complete somersault and came to his feet holding the baseball! Carlisle sprinted to second base to double Moore off and then trotted to first and tagged the bag, completing the unassisted triple play. Vernon went on to score two runs in the ninth and beat the Angels 5-4. It spoiled an otherwise fine performance by Delhi, who hit his only home run of the season in the second inning. The blast over the left-field fence was said to be “a mighty swat, worthy of an Atlas or a Hercules.” Carlisle said, “Backed by a winning team, Flame Delhi would never lose a game. That may sound like a strong statement, but (it) will be easily understood by the men who have faced Delhi. He has everything – tremendous speed, fine control, good curves and an excellent slow ball.” Praise for Delhi was commonplace in the newspapers and he was often referred to as the next Orvie Overall, Tacoma’s 32-game winner for its 1904 championship team who went on to twice win twenty games in the major leagues and post one of the best career ERAs of all-time (2.24). At only 18 years old, Flame Delhi was the best pitcher in the Pacific Coast League.

On June 21 Henry Berry, the president of the Angels, received a telegram from White Sox owner Charles Comiskey asking Berry to set a price on Flame Delhi. Although other teams would join the bidding, the White Sox eventually won Delhi’s contract for $5,000. It was reported that this was the highest price paid for a Coast League pitcher up to that time. Delhi was to report to the White Sox for the 1912 season but would be allowed to finish the 1911 season with the Angels. Late in the year, Delhi threw only 75 pitches in a Sunday afternoon game, an apparent professional record for the fewest pitches in a game. His record would stand until 1940 when Julio Bonetti of the Angels would throw only 66 pitches in a victory over Oakland. It was quite a year for the youngster. In all, he pitched in 57 games, winning 27 and losing a league-high 23. He also led the PCL in complete games with 43, an Angels club record that still stands. Flame struck out nearly twice as many batters (187) as he walked (98).

Besides establishing himself as the best pitcher in the West, Delhi was earning a reputation as an all-around athlete. He beat Carl Mueller in two straight games (21-8 and 21-3) to win the Southern California Athletic club handball tournament. According to a Los Angeles-area newspaper, later in the summer he showed up at Ocean Park in “one of the loudest bathing suits of the season.” It was said to be “the attraction of all those present on the beach.” He entertained the crowd by demonstrating the cutaway, corkscrew, pile dive and several other stunts.

As his fame grew, so did his legend. One scribe wrote of Lee’s days in Arizona, “All that the little Flame knew about the world in those cactus salad days was cows, horned toads, castor oil and burros. His chief form of amusement was in tossing ground apples at slab-sided, long-horn steers.” An article from a Chicago paper that was in Delhi’ s scrapbook said that he played on Pomona University’s football team for three years, was the team’s pitcher, best basketball man, the best handball player and best swimmer at the university. He never attended the school. Delhi scribbled ‘BS’ across the article.

Celebrity endorsements aren’t anything new. In November, following his spectacular 1911 season, Delhi and Johnny Kane of Vernon were featured in a Bullock’s advertisement and then made appearances at the store. The ad told readers that “Flame Delhi says – ‘Every boy in Los Angeles should come to Bullock’s for his new suit and overcoat. Honestly, the best values I ever saw are here in the store for your boy – Santa Claus, Johnny Kane and I have formed a partnership that means much to you and everyone.’”

Delhi played winter ball again and then headed to Waco, Texas, for the start of spring training with the White Sox. Temperatures in Waco were frigid and the club held morning practices inside. A Chicago newspaper reported “Delhi threw on the side for 45 minutes today and looked good … .in spite of the near freezing temperatures.” Delhi had an assortment of pitches including a slow underhanded twister and a knuckleball. When asked what his best pitch was, Flame told reporters: “I reckon my cross-fire, side arm and by hook. I have been willing, of course, to sacrifice speed at times for control.” He went on to explain that he could throw just about any pitch except the spitter, which he never learned and didn’t intend to. On March 9 he was one of three pitchers used by the White Sox in an exhibition game against a local team in Houston. Two days later Delhi pitched three innings in and intersquad game at Waco. While the weather was sunny, a cold wind continued to chill the players and make conditions uncomfortable. Shortstop Buck Weaver made two errors behind Delhi, causing the recruit to lose the game 3-2. The teams played only five innings because of the icy wind and to allow Baylor University to use the field for their regular practice in the afternoon. On the 16th, in a seven-inning game, Delhi beat a local team in Fort Worth 10-1. A terrific wind blew throughout the game. Lee had made the team and headed back to Chicago with the club. On the road back the White Sox stopped to play games in Oklahoma City on April 3 and Wichita on April 4. Delhi pitched in both games. In the first game in Oklahoma City, he allowed just two hits, no runs and struck out eight in four innings of work. The next day in Wichita he was less effective as he again pitched four innings but gave up three runs and struck out only two. One can only speculate if the combination of throwing in cold weather, overwork with the Angels and pitching two days in a row in April ruined Delhi’s arm. In any case, he did not pitch again until his lone regular-season appearance of April 16, 1912.

In the spring of 1912, Arizona was still growing up. After all, the former territory had only gained statehood in February and most of the country still thought of Arizona as the untamed Wild West. It’s not surprising that the first major league appearance by Flame Delhi, a rookie pitcher for the Chicago White Sox, went largely unnoticed. It probably wasn’t even noted in any newspaper that Delhi was the first Arizonan to play big league baseball. The headlines of the Chicago newspapers on April 16 were dominated by the sinking of the Titanic, which had gone down just a day earlier. The next day, with the news of the Titanic disaster still dominating the headlines, the Chicago American reported on the Tigers-White Sox match-up by noting that the day was “too cold to play baseball … and the White Sox performed as if they knew it.”

About 3,000 fans braved the cold and the threat of rain to watch the Sox take on Detroit. The Tigers were without the services of the great Ty Cobb. The Georgia Peach was on a train headed back to Detroit. It seems that the room Cobb was assigned at the Chicago Beach Hotel was next to the Illinois Central railroad tracks. Cobb complained about the noise and was told that he couldn’t be moved to another room but could be put up in another hotel. Ty was furious. He demanded that the whole team be moved to another hotel. When his demand was declined, he refused to play and jumped a train home. A young outfielder named Hank Perry replaced Cobb in the lineup that day.

Perry would be the first batter Delhi faced in the major leagues. With the Sox already trailing 4-0, Delhi came on to pitch in the top of the seventh inning. Hank ‘Socks’ Perry had made his big league debut just six days earlier. His career, like Delhi’s, would be brief. For Perry, 1912 would be his only big league season. It was a season that saw him play in only 13 games. This would be his greatest day in baseball as he went 2-for-6 against the Chisox. He ended the season with six hits in 36 at-bats, a .167 average.

As the seventh inning opened, it was two youngsters trying to make their mark. One in the lineup replacing the legendary Ty Cobb, the other thrown out there to save the regular pitchers’ arms on a blustery day in Chicago.

Flame showed the smoke that had gotten him to the big leagues as he struck out Perry. It would be the high point of his major league career. The next batter was future Hall of Famer Sam Crawford. Wahoo Sam slammed a shot back through the box right past Delhi’s ankles and into center field for a single. Del “Sheriff” Gainer, the Tigers’ first baseman, followed Crawford to the plate. Gainer grounded out softly to Buck Weaver at shortstop with Crawford taking second on the throw – two outs. With shortstop Donie Bush at the plate, Crawford stole third, one of 42 steals on the season for the Tigers’ outfielder. Bush then worked Delhi for a walk. It was one of the light-hitting shortstop ‘s league-leading 117 free passes that year. Bush, in spite of a lifetime average of only .250, led the American League in walks five times, including four years in a row (1909-12). At 5-foot-6 and 140 pounds, the diminutive infielder used his size to his advantage. Charlie O’Leary stepped to the plate with runners at the corners. O’Leary had been the Tigers’ regular shortstop 1904-07, but by 1912 he was playing second base and was in decline. He would play in only three games that season before being released. In the off-season O’Leary and former teammate Germany Schafer would work a vaudeville act together. On the first pitch to O’Leary, Bush took off for second. When White Sox catcher Bruno Block threw down, Crawford raced toward the plate. The relay home was late and both runners were safe after having pulled off the double steal. Delhi then struck out O’Leary to end the inning.

In the bottom of the seventh inning and trailing 5-0, the Sox tried to rally as Callahan and Bodie singled. Matty McIntyre then pinch hit for Chick Mattick. McIntyre lined a shot that was speared by O’Leary. He flipped the ball to Bush at second to double off Callahan. Bush then threw to first in time to catch Bodie off base – triple play! Incredibly, Delhi’s club had again been victimized by a triple killing when Flame was the pitcher.

With the triple play, the Sox lost any chance they had for a comeback. In the eighth inning it looked as though the club had lost all of its spark. Flame was unable to get the bottom of the order out in the inning. Light-hitting catcher Oscar Stanage led off with a single up the middle followed by a single by the pitcher, Ed Willett. For Willett, a .165 hitter on the year, it was a big day. It was his third hit of the game in a season in which he managed just 19 hits. The leadoff hitter, rookie outfielder Ossie Vitt, grounded to Weaver with Willett moving to second and Stanage holding at third. Baldy Louden drew a walk to load the bases and bring up Perry. It looked like Delhi might escape the inning when Perry grounded back to the box and Flame threw home to force Stanage for the second out. But the next batter, big Sam Crawford, grounded a shot past Weaver, scoring Willett and Louden. Perry tried for third but was thrown out by Callahan to end the inning.

After the White Sox failed to score in the eighth, Delhi returned to the mound for the ninth. Gainer reached on Weaver’s error, and Bush walked for the second time against Flame. O’Leary grounded out, advancing the runners and Stanage singled to center, scoring both runners. Willett singled to center with Stanage stopping at second. Vitt singled to center to load the bases, and Louden singled past Delhi to score a run and leave the sacks full. Perry then hit back to Delhi who again threw home for the force out. Crawford mercifully flied to right to end the inning, three runs having scored. Of the nine outs Delhi recorded, four were accounted for by Perry, who struck out, grounded into two force plays and was thrown out trying to go to third base on a single. When Flame Delhi left the mound, he surely didn’t realize that there wouldn’t be another day. His career as a major leaguer was over. Delhi was pinch-hit for to lead off the ninth and never would appear in another big league game. The White Sox lost that day 10-1 but Arizona had seen its first native son play big league baseball.

Flame had also left another legacy behind in Chicago. He was part of the composite that made up Jack Keefe, the bush leaguer in Ring Lardner’s “You Know Me Al” stories. In an interview with Ping Bodie that was published by The Sporting News in 1940, Bodie talked about his role in Lardner’s work: “Naw, I wasn’t the Al in the ‘You Know Me Al’ series that Ring Lardner wrote. I was the stoolie for Lardner. That character was a combination of Flame Delhi – he’s president of Western Pipe and Steel now – and old Reb Russell. I roomed with both of them at different times and I’d tell Lardner what they said and he’d use it in those letters. That Lardner could write a bit too.”

A month after his ill-fated pitching performance in Chicago, Delhi was sold to San Francisco in the PCL. After joining the Seals, Delhi never could get it going. He was constantly bombed out of the box and the fans and the newspapers turned on him. One paper accused him of “dogging it.” Fans would boo when he took the mound and the sensitive Delhi, still only 19 years old would cry. He didn’t tell anyone that his arm was dead, although it became obvious that he didn’t have the same smoke on the ball that had gotten him to the big leagues. After a dismal 1912 season, a 5-8 record in 16 games and just 99 innings, Delhi was told to take the winter off and come back ready to pitch next year. For the first time since 1908, Delhi didn’t play winter ball. When he returned to the Seals for the 1913 season, he was made to take a pay cut which hurt his pride. He was determined to show the league that he could still pitch. He was given just three starts in which he was battered for 36 hits and 19 runs in only 26 innings and the Seals released him. The May 8, 1913, issue of The Sporting News reported his release:

“The release of Delhi suggests that he was perhaps the most bitter disappointment ever inflicted upon a Coast manager. … Delhi was unable to get himself into shape all last season. He complained of a sore arm much of the time, and when he was able to take his turn, his arm seemed to have lost all its effectiveness. When he reported to San Francisco at Boyes Springs in March he looked like a real comeback. In fact, he made a great showing against the White Sox in a practice game and was generally expected to be a mainstay of the Seal staff in the regular season. But his work was miserable. He was batted all over the lot with absurd ease. After starting him about four [sic] times and being satisfied he could not get into form, Howard decided to release him. A year’s rest may do Delhi good and he will be a free agent if he ever wants to start again.”

Delhi didn’t want to rest; he wanted to pitch. He talked Herb Hester, the Great Falls manager in the Union Association, into giving him a chance. Although it was only Class D ball, it was still baseball. At that level Delhi dominated. Not only did he post a 22-10 record in 34 games on the mound, he also played 28 games in the outfield and batted .312 with five home runs. His performance prompted the Pittsburgh Pirates to give Delhi a chance to make the club in 1914.

Although he was still having arm problems, the Pirates carried Delhi into the season and even talked about making him into an outfielder. He roomed with the immortal Honus Wagner and would later say that Wagner was the greatest player ever. In May Pittsburgh sent Delhi to John D. “Bonesetter” Reese, a Youngstown, Ohio, chiropractor who had gained a reputation for quick cures. Even the miracle worker couldn’t repair Delhi’s lame arm and later that month Flame was released to Kansas City of the American Association.

Playing the outfield and pitching for the Blues in 1914, Delhi posted a 12-11 record in 32 games and batted .246. He returned to Kansas City for the 1915 season and his comeback was complete as he pitched 325 innings, posting a 2.60 ERA and a 21-15 record in 47 games. Delhi’s wife Rose hated Kansas City and longed to return to the coast. With Delhi’s comeback came a three-cornered battle for his services. Barney Dreyfuss, the owner of the Pirates, claimed that Delhi was sent to Kansas City with the understanding that the Blues would have to pay a large sum of money if they wanted to keep him. Blues owner George Tebeau refused to give the Pirates any money and Pittsburgh sold his contract to the Angels of the PCL. Tebeau said he would not allow Delhi to go to the Coast League even though that is where the pitcher wanted to go. Delhi was caught in the middle. He had been promised a $400 bonus if he won 60 percent of his games in 1915 (21-15 came to .583, but for some reason the papers reported that he had won the bonus by winning at a .600 clip.) The National Commission awarded Delhi’s rights to the Angels. The Blues’ owner told Delhi he would pay him the $400 bonus only if he reported to Kansas City, but the National Commission ruled that if he reported to the Blues, Delhi would be banned form organized ball. Lee and Rose didn’t like living in Kansas City and longed to return to their Los Angeles home. For them the decision was easy. They would pass up the $400 and return to the Angels.

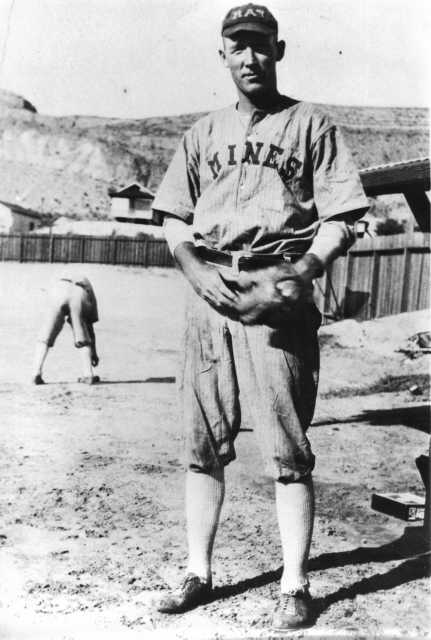

In the meantime, an interesting development took place. Delhi’s old friend Herb Hester from Great Falls was scouting players for an Arizona league. He presented Delhi with a unique proposition: If Flame would come to Arizona and play for the Ray Copper Mine team in the Copper Belt League, the company would teach him civil engineering. As much as Delhi wanted to return to Los Angeles, he recognized the need to learn a trade. After all, he couldn’t pitch forever. In 1916 Delhi moved to Ray, Arizona, to play for the company team. The Angels put him on their restricted list hoping he would someday return to the PCL.

Following the 1917 season, Delhi decided to return to organized baseball and the Angels. He and Rose returned to Los Angeles, where Flame played winter ball. During this time Rose became pregnant. Lee, on the verge of becoming a father, reconsidered taking up pitching again and returned to Ray. In March 1918, Delhi’s only child was born in Los Angeles. Six months later, Rose and baby Marjorie joined Flame in Arizona. Life in Ray was not easy. Rose would grease the legs of Marjorie’s crib with lard so centipedes couldn’t crawl up and bite the baby. Flame used a garden hose and a tin can with holes in it to make a showerhead. These were city folks living in the desert.

By 1920 Delhi, his wife and daughter had moved back to California, where he landed a job on a construction crew in El Segundo. Four years later he started a 22-year career with Western Pipe and Steel. He rose to the company’s vice presidency and was in charge of shipbuilding operations. He was one of the leading proponents of arc welding and pioneered building all-welded ships with no riveting. Under Delhi, Western Pipe and Steel completed more than 40 ships for the war effort in the 1940s. Lee W. Delhi, in his San Francisco Chronicle obituary, was called “a titan of western steel.” He served as the national president of the Welders Society of America and the president of the California Metal Trades Association. Delhi commanded a salary of more than $80,000 a year at the height of the Depression.

In 1946 Western Pipe and Steel was sold to Consolidated Steel of California. Delhi resigned to join the engineering firm of Hunt, Mirk and Co. He continued to be a nationally known industry leader. Later in life he acted as a consultant to the steel industry.

Lee and Rose separated in the 1930s and lived apart for the rest of their lives although they never divorced. In retirement Flame would tell baseball stories to his grandchildren while sipping on lemonade and gin.

Lee William “Flame” Delhi died at Marin County Hospital in Greenbrae, Calif., May 9, 1966, with his daughter at his side.

Sources

Much of the material for my research on Flame Delhi came from The Flame Delhi Scrapbook. This scrapbook was put together by Marjorie Prince, the daughter of Flame Delhi. She pasted numerous newspaper clippings in the book and presented it to her father for Christmas in 1941. The clippings were saved through the years by Mrs. Prince’s mother. The scrapbook is now available to researchers at the Arizona Historical Foundation located on the second floor of Arizona State University’s Hayden Library. Many of the included newspaper articles, from 1908-1940, are unidentified and undated.

Newspaper clippings from the scrapbook I could identify include:

Los Angeles Express

Los Angeles Examiner

Los Angels Times

Los Angeles Herald

Oakland Tribune

Chicago Record Herald

Chicago American

Unidentified newspapers from:

Kansas City

Pittsburgh

Arizona

Santa Monica

Los Angeles

Additional material provided to the author by Mrs. Prince included:

Articles from The Welding Journal (June 1941).

Company documents from Western Pipe and Steel.

Documents and correspondence from the American Welding Society.

Various other trade publications.

Various original photographs from family archives.

Interviews and correspondence with Mrs. Prince.

Other Sources

Newspapers:

Chicago American: April 17, 1912.

Chicago Tribune: April 17, 1912.

Los Angeles Examiner: Many dates, 1910-1912.

Santa Monica Daily Outlook: March 12, 1909; April 2, 1909.

San Francisco Chronicle: Many dates; 1912-1914.

Periodicals:

The Sporting News: Many issues, 1909-1941.

Books:

Barnes, W.C. (1988). Arizona Place Name s.

Obojski, R. (1975). Bush League.

O’Neal, B. (1988). The Pacific Coast League.

Thorn, J., Palmer, P. (EDS) (1991). Total Baseball: Second Edition.

Trimble, M. (1989). Arizona: A Cavalcade of History.

Turkin, H., Tompkins, S.C., eds. (1956). The Official Encyclopedia of Baseball.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Bob Hoie, Dick Beverage for help with Delhi’s statistical record and information about the Pacific Coast League. Also, thanks to George Hilton for his help with information about Delhi’s brief time with the White Sox.

Full Name

Lee William Delhi

Born

November 5, 1892 at Harqua Hala, AZ (USA)

Died

May 9, 1966 at Greenbrae, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.