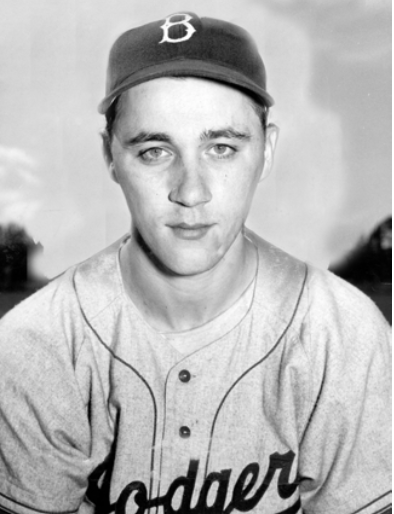

Billy Loes

In a widely circulated national profile of the Brooklyn Dodgers’ Billy Loes in the Saturday Evening Post in 1953, journalist Jimmy Breslin described the young hurler as a “Dizzy Dean from the sidewalks of New York.”1 That reference would not have been lost on readers at the time. The former 30-game winner Dean parlayed his down-home, country-boy personality into one of the most recognizable baseball broadcasters of the 1950s. The youthful Loes, on the other hand, made headlines for his wacky statements and bizarre, typically candid pronouncements that left many wondering whether he was cocky, stupid, or a combination of both.

On the eve of the 1952 World Series, Loes found himself in a mini-controversy when reporters asked him to clarify his prediction that the New York Yankees would beat his Dodgers in six games. Claiming that he was misquoted, Loes responded, “I never told that guy the Yanks would win it in six. I said they’d win it in seven.”2 Loes almost had the chance to foil his own prophecy by holding the Yankees scoreless through six innings in Game Six, with Brooklyn leading three games to two. A sequence of peculiar events led to his unraveling in the bottom of the seventh and an eventual Yankees victory. Loes was charged with a balk when he dropped the ball in his windup and then misplayed a grounder back to the mound leading to a run. Afterward, Loes calmly explained his miscues in his strong New York City accent and gruff, profanity-ridden language (which sportswriters liberally edited): “I might have had the [expletive] thing if it wasn’t for the low sun shining in my face”3

Loes cultivated his zany persona, which many sportswriters and fans considered part of Brooklyn’s screwball tradition dating back to the “Daffiness Boys” of managers Wilbert Robinson and Casey Stengel more than a generation earlier. The team’s “right-handed weirdie” was a typical epithet for Loes.4 Prior to the 1952 season, Loes told reporters that no Dodgers pitcher would win at least 15 games, and then made an early-season amendment. “Better make it seventeen,” he said after his hot start. “I looked pretty good out there today.”5

Loes once claimed he never wanted to win 20 games because then the Dodgers would expect him to win that many every year, and would cut his salary if he didn’t. Twelve or 13 wins would be plenty, he suggested.6 Oddball comments like those might have made him a quirky favorite of fans, but they exasperated his managers and the front office. “How can the public be so gullible?” said Loes in 1956, after he had been traded from the Dodgers to the Baltimore Orioles. “Don’t the people know that most of the stories are phony?”7

Loes was a complicated and unpredictable player, filled with contradictions and myriad superstitions. Behind what Brooklyn beat writer Tommy Holmes called a “brusque exterior,” Loes was a brooding type away from the game, yet a practical joker and clown with teammates.8 However, he never seemed at home with reporters, despite his penchant for good copy; rather, he often brushed them off with “I don’t know nothing about anything.”9 Nervous and fidgety in the dugout on game days, Loes was more at ease on the mound, where he was typically undemonstrative. Later in his career he developed a reputation for arguing with umpires and even his catcher.

“I used to think Durocher was a nut on superstitions,” said Dodgers skipper Chuck Dressen, “but this kid is even worse.”10 According to Dressen, Loes dropped his glove in a certain spot in the dugout after arriving from the mound each inning, and it had to land in a specific way; and he could go to the mound only after the opposing base coaches got into position. Whereas many pitchers like to be left alone between innings, Loes sat in a same spot in the dugout and chatted with the same teammates every time, and required a few words of encouragement from Dressen each inning on his way back to the mound. He also went through periods when he refused to talk on the mound, including to his manager. Despite his eccentricities, Loes was generally well liked by his teammates. Many of them no doubt laughed when Loes once demanded that the Dodgers pay for a stray dog he took home to his mother as a legitimate business expense.11

Loes was praised as having unlimited natural talent, while his work ethic and attitude were publicly questioned by his managers, and he was dismissed as a flake. “Loes wears an aggravated look constantly, as if Lady Luck mistreats him with steady rudeness,” wrote sportswriter Arthur Daley in the New York Times in 1956. “He also seems to carry a chip on his shoulder … and thinks that he has received bad press without justification.”12 Loes’ volatile personality and blowups contributed to that impression. “The only thing I like about baseball is the salary,” he told Jack Orr in a Sport profile in 1958. “I never get a kick out it. I haven’t got one of these feelings that it’s the greatest thing in the world. It’s just a job.” Plagued by chronic shoulder pain throughout his career, Loes never reached the potential many predicted, finishing with an 80-63 record in parts of 11 big-league seasons, including a stellar 50-25 slate with Brooklyn from 1952 to 1955.

William Loes was born on December 13, 1929, in Long Island City, New York, and was raised in Astoria, about a half-hour from Ebbets Field. (Both Long Island City and Astoria are sections of the New York City borough of Queens.) He was the only child of James and Filo Loes, Greek immigrants who, according to Loes, had shortened their surname. The younger Loes lived in a small apartment and grew up with limited means. The elder Loes suffered a debilitating injury while serving in the Maritime Service in World War I, and did not work; Billy’s mother provided for the family by working in a furniture store. By the time Billy was a teenager, he was obsessed with baseball. He worked to save some money to attend occasionally a big-league game. Like many other kids, he played on local sandlots and in the street, pretending to pitch to the likes of Joe DiMaggio and Bill Dickey, and began playing for a local YMCA youth team.

Loes emerged as one of New York City’s best pitchers during his last two years at William Cullen Bryant High School in Long Island City. After his junior year he led the Astoria Cubs to the Kiwanis League state title in the summer 1947, and was selected as the most valuable player.13 At 6-feet-1 and just 150 pounds, Loes possessed a wicked curveball that helped him fashion five no-hitters (four as a senior), the last of which was in the semifinal game of the 1948 Public School Athletic League championship with a flock of big-league scouts in attendance.14 The overly confident teenager often tooted his own horn, angering friends and foes alike. “I was misunderstood in high school,” he once said. “There’s a difference between cockiness and confidence.”15

Loes finished his prep career by tossing a one-hitter and knocking in the winning run to lead coach Vince Starace’s squad to the title.16 For his MVP performance, he won a weeklong tour with the New York Giants. Upon returning home, the legend of Loes’ head-scratching comments was cemented when he compared himself to the Giants’ star righty Larry Jansen and boldly announced, “I forgot more [about pitching] than he ever knew.”17

In baseball’s postwar big-bonus era, Loes was angling for a hefty payday from teams lining up to sign him. Tom Yawkey, owner of the Boston Red Sox, had been fined by Commissioner Happy Chandler for attempting to ink the teenager while he was still in high school, a serious transgression at the time.18 As a member of the Brooklyn Eagle All-Stars after graduating from school, the 18-year-old Loes dominated competition on a traveling tour against other all-star squads in Washington, D.C., and Canada.19 At the tour’s conclusion, Loes played semipro ball in Queens.20 He became one of the most sought-after pitchers in New York after an excellent outing in a showcase game with scouts from supposedly all 16 big-league clubs except the Yankees and Dodgers.21 The Cleveland Indians offered the precocious youth an $18,000 signing bonus, yet Loes hesitated.

The Dodgers, sensing an opportunity, had one last chance. After working out in front of Dodgers brass at Ebbets Field, Loes accepted GM Branch Rickey’s offer of a $21,000 bonus, the largest in club history at the time, and signed with Brooklyn. “I knew I wasn’t worth no big dough,” said Loes in typical fashion in the Saturday Evening Post piece, “but I figured those kids weren’t worth it either.”22 Rickey seemed to agree, but knew that it would be public-relations nightmare had the New York City native signed elsewhere. “He’s just about a $10,000 player,” said the Mahatma, “but Loes is a local boy and I just can’t let another club sign him.”23

During the Dodgers minor-league spring training in Vero Beach, Florida, in 1949, Loes’ “every move was followed closely” reported Brooklyn sportswriter Ben Gould.24 Loes began his professional career with Nashua in the Class-B New England League, where he blazed a trail, going 11-3, including a no-hitter, before he was promoted to Fort Worth in the Double-A Texas League. With a combined 16-5 record and 2.69 ERA in 194 innings, Loes was added to the Dodgers’ big-league roster in mid-October.25 Under the bonus rules then in effect, Loes would have otherwise been eligible for the amateur draft slated in November, and was required to remain on the Dodgers’ roster for the entire 1950 season.

Obviously not yet prepared to face major-league hitters, Loes’ rookie campaign in 1950 was a washout. The 20-year-old hurler languished on the far end of skipper Burt Shotton’s bench, primarily confined to the role of BP pitcher, logging just 12⅔ innings and yielding 11 earned runs. He debuted in mop-up duty against the St. Louis Cardinals on May 18, walking five, balking once, and surrendering one hit (a two-run homer to Johnny Lindell) in two innings.

While Loes’ skills rusted on the bench, his career encountered another setback when he was drafted into the Army and inducted in early February 1951.26 Stationed primarily at Fort Devens in Massachusetts, Loes served with the 314th Quartermaster Subsistence Company. He pitched for the base team in the semipro Blackstone Valley League and against other military base squads.27 In mid-October he received his discharge as a hardship case, citing his financial support of his parents. Two years later, he purchased them a house with his 1952 World Series earnings.28

Loes was itching to play baseball, but only on the big stage in 1952. He supposedly told second-year pilot Chuck Dressen that he’d quit baseball if he were demoted. “I’ve learned all any minor-league manager can teach me,” said Loes. “I’d be wasting my time down there.”29 Described already as “insufferably conceited” by beat writer Roscoe McGowen, Loes had a surprisingly productive spring, and then shocked his team in the Dodgers’ home opener on April 18 by hurling five scoreless innings of two-hit ball to pick up the victory over the New York Giants in 12 innings. After yielding just two earned runs in 19 innings of relief, Loes tossed a six-hit shutout against the Pittsburgh Pirates on May 15 at Ebbets Field in his first big-league start. Two starts later, he blanked Philadelphia on five hits at Shibe Park.

Hurling consistently all season long as a starter and reliever, Loes emerged as one of the Dodgers’ most effective hurlers. While the Bums captured their second consecutive pennant, Loes posted a 13-8 record, including four shutouts, and a 2.69 ERA (fourth lowest in the NL) in 187⅓ innings.

Facing the Yankees in the World Series for the third time in five seasons, the Dodgers had a chance to capture their first, elusive championship in Game Six at Ebbets Field. Dressen called upon Loes despite the right-hander’s shaky relief outing in Game Two (two hits and two runs in two innings). Loes mowed the Yankees down through six before Yogi Berra led off the seventh with a home run to tie the game, 1-1. Loes committed a balk two batters later, then misplayed Vic Raschi’s two-out grounder, which bounced off his knee and caromed into right field, enabling Gene Woodling to score. In the bottom of the frame, Loes singled and then added to his growing legend for zaniness by stealing second. Whether it was a failed attempt at a hit-and-run by Billy Cox or Loes’ own idea will forever be a mystery. Loes himself, however, took credit for the adventure: “I just saw nobody was watchin’ me, so I ran to second.”30 In the eighth, Loes yielded a towering home run to Mickey Mantle, and was ultimately charged with the loss (nine hits and five walks in 8⅓ innings). The Yankees broke Brooklyn’s collective heart the next day by capturing the title with a 4-2 victory.

While his comments about being blinded by the sun looking down to field a grounder added to his eccentric reputation, Loes found himself embroiled in a less savory episode just weeks after the World Series when a warrant for his arrest was issued in New Jersey as part of a paternity suit. The Dodgers front office brushed off the case as yet another example of “blackmail”31; and indeed the case was eventually thrown out four years later.

Loes was often described as a good-looking player, with a dark complexion and dark eyes situated on a thin baby-face. He bulked up to about 175 pounds, but never put on the weight that his managers thought was necessary to be a durable ace, and always appeared thin. According to Breslin, Loes was “popular with the bobby-soxers”; however, the eligible bachelor initially preferred spending his nights at home, where he resided with his parents during his tenure with the Dodgers.32

Loes’ success rested on four pitches: curve, fastball, changeup, and, beginning in 1952, a slider. In Loes’ rookie campaign, the Dodgers felt that he lacked a serious heater, though Dressen later claimed that was a mistake, and that “he was faster than the average pitcher.”33 Brooklyn’s MVP catcher Roy Campanella was more direct in his assessment: “He’s got the best fastball in the National League.”34 Loes had a fluid, graceful pitching motion, as can be seen in the video of Game Six of the 1952 World Series.35

Highly touted as a possible 20-game winner in 1953, Loes emerged as Brooklyn’s only reliable starter in the early part of the season. By the end of June he had won 10 games, but had also been hit hard in some contests, resulting in a bloated 4.49 ERA. After that Loes was a “complete loss for two months,” opined Brooklyn sportswriter Dave Anderson, plagued by shoulder pain that would accompany the hurler for the remainder of his career.36 It was during that stretch (on August 23) that Breslin’s piece in the Saturday Evening Post appeared, causing quite a stir. A sensitive Loes threatened to sue (though he didn’t refute the portrayal) while Tommy Holmes of the Brooklyn Eagle thought it made the pitcher look like a “Simple Simon.”37 On September 7 Loes tossed a complete-game four-hitter against Philadelphia to win his first start in two months, and suddenly his name was bandied about as a possible World Series starter for Brooklyn, which was then cruising to a franchise-record 105 wins.

With the Dodgers trailing the Yankees two games to one, Loes (14-8, with a 4.54 ERA in 162⅔ innings) battled his friend and fellow Astoria resident, Whitey Ford, in Game Four, at Ebbets Field. While Ford was knocked out after one inning, Loes scattered eight hits and gave up three runs over eight frames to earn his only World Series victory, 7-3. The Bronx Bombers, led by Billy Martin’s heroics, took the next two games to capture their record-setting fifth consecutive championship.

Chided as a “crazy, mixed-up kid — even unpredictable in the Spring,”38 Loes embroiled himself in yet another brouhaha in spring training 1954, with the statement, “I hate baseball,” claiming to prefer a 9-to-5 job.39 Those comments drew the ire of local sportswriters who had berated him as too sensitive since the Breslin episode. Loes suffered a severe elbow injury in late April and pitched sporadically and poorly afterward, leading new Dodgers skipper Walter Alston to chastise him publicly as a “mystery” whose pitches were “half-dead.”40 Just when it appeared that Loes had lost it, he tossed an overpowering complete-game victory against the Pittsburgh Pirates, whiffing a career-best 11, on July 5. Defying expectations, he won his next eight decisions, including five straight starts in August, keeping Brooklyn in a tight pennant race with the Giants. But Loes slumped in September, re-aggravating his elbow and shoulder injuries, and was ultimately exiled to the pen. A seemingly exasperated Alston, who rarely complained about players in the press, openly questioned Loes’ mental preparation and commitment as the Dodgers finished in second place, five games behind their crosstown rival Giants.41

Shortly after the 1954 season, Loes made his first and only appearance in a film, Roogie’s Bump.42 The comedy was about a young Flatbush boy, Remington Rigsby; his nickname is Roogie. The actor who plays him is Robert Marriott. Roogie develops a bump on his arm that enables him to throw with great speed. He eventually lands a spot on the Dodgers.43 Four of his teammates are real-life Dodgers — Roy Campanella, Carl Erskine, Russ Meyer, and Loes, all of whom play themselves. Film critic Jane Corby of the Brooklyn Eagle was excited by some action shots of the team and Ebbets Field in the film, but added, “the story is weak.”44

Despite a 13-5 record and 4.14 ERA in 147⅔ innings in 1954, there was a “feeling that Loes could have been much better,” wrote Roscoe McGowen.45 It was the typical refrain heard about the hurler who drew charges of indifference. In the offseason, GM Buzzie Bavasi expressed his frustration by remarking that “Loes is old enough now to realize he’s got to settle down.”46 The United Press opined that “nobody takes baseball less seriously and gets more results than Brooklyn’s unorthodox Billy Loes.”47 Bothered by shoulder pain most of the 1955 season, Loes pitched well when he could (19 starts), including matching his career high with 11 strikeouts in a complete-game win against Chicago on June 11. On September 7, after being sidelined for a month, Loes tossed a stellar complete-game six-hitter to defeat the Milwaukee Braves at County Stadium and give the Dodgers at least a tie for the pennant. Few could have guessed that it would be Loes’ last victory as a Dodger.

While “Dem Bums” finally beat the Yankees in the World Series in seven games, Loes’ start in Game Three was deemed a “complete failure.”48 After hurling just 18 innings in September, Loes shook off the rust to toss three scoreless frames before imploding in the fourth. He was charged with the loss (seven hits and four earned runs in 3⅔ innings) and tied a World Series record by hitting two batters.

Loes endured so much shoulder pain during spring training in 1956 that he threatened to quit baseball altogether. He didn’t, but the Dodgers cut their ties with the oft-injured hurler on May 14 by selling him in a waiver transaction to the Baltimore Orioles. “For four years we’ve been waiting for him to produce,” said Bavasi. “I’m beginning to wonder how long it’ll take. His trouble is he has no sense of responsibility.”49 Loes, who made just one disastrous start before the deal (five hits and six runs in 1⅓ innings), welcomed the change of scenery. “I just couldn’t get comfortable in Brooklyn,” he claimed. “I was always under too much strain.”50 Loes transitioned into the bullpen with Baltimore with middling results (2-7, 4.76 ERA in 56⅔ innings).

With few expectations for success, Loes emerged as one of the feel-good stories of the first half of the 1957 season. Beginning with a complete-game 11-2 victory over the Kansas City A’s on May 8, he won eight consecutive decisions in the best stretch of pitching in his career. He completed six of nine starts, posting a 1.89 ERA in 71⅓ innings, and spun two shutouts, including the best game of his career, a sparkling three-hitter with no walks against the A’s on June 25 as part of the Orioles’ record-tying four consecutive shutouts. “I know his arm has been sore, but he’s still young enough to recover,” said Orioles GM-manager, Paul Richards, who appeared to have fleeced the Dodgers.51 When asked to explain his sudden success, Loes responded in usual curt fashion: “Luck and a bigger ballpark.”52

Selected by Casey Stengel to his first and only All-Star Game, Loes followed starter Jim Bunning’s three hitless innings with three scoreless innings of his own, yielding just three hits, which probably made Walter Alston, skipper of the NL squad, squirm on the dugout bench. Loes improved his record to 12-5 with his third shutout of the season, on August 4, but it proved costly. He reinjured his elbow and was confined to the bullpen, save for one start, for the rest of the season.

There was no fairy-tale return for Loes in 1958, as he lost his first seven decisions (all as a starter). His career may have reached its nadir in an ugly incident on June 1 in Baltimore. Trailing 1-0 in the fifth, Loes caught Bob Aspromonte of the Washington Senators in a rundown between third base and home after retiring Camilo Pascual on a grounder to the mound. Loes took matters in his own hands and attempted to chase down Aspromonte himself. When Aspromonte eluded his tag and was called safe by home-plate umpire Larry Napp, Loes went ballistic. He threw the ball in disgust against home plate and shoved Napp. Julio Becquer, on first via a single, rounded the bases to score. Loes was immediately ejected, and subsequently earned a fine and suspension from the AL, and also by the Orioles for “deliberately throwing away a game.”53 Loes took his frustrations out on the autocratic Richards. “He doesn’t care whether you win or lose, just so that you don’t make him look bad,” said the volatile hurler. “He’s got all the pitchers on this club scared to death of him.”54 Despite rumors that he’d be traded, Loes remained with the club, spending the final three months of the season in the bullpen.

An exasperated Richards was desperate to rid the club of the sore-armed Loes in 1959. “Know anyone who wants him?” he asked rhetorically in mid-March.55 Richards found a taker, sending Loes to the Washington Senators on April 1; however, the trade was voided by Commissioner Ford Frick eight days later when Loes was incapable of pitching. Back with Baltimore, Loes found yet another of his nine lives, pitching effectively much of the season as a reliever, recording 14 saves, before his aching wing limited his effectiveness in the final two months of the season.

Loes spent his final two big-league seasons with the San Francisco Giants when Baltimore traded him along with pitcher Billy O’Dell for infielder Jackie Brandt, pitcher Gordon Jones, and catching prospect Roger McCardell on November 30, 1959. Confined to mop-up duty in 1960, Loes had a surprisingly productive spring in 1961 and earned a spot in skipper Al Dark’s rotation. Given ample time between outings, Loes enjoyed some early-season success, tossing the last of his nine career shutouts on May 7, blanking the Philadelphia Phillies on seven hits. Inconsistent and injury-plagued, Loes (6-5, 4.24 ERA) logged 114⅔ innings, his most in three years, but wasn’t in the Giants’ long-term plans.

In the offseason Loes was sold conditionally to the expansion New York Mets, but quit in a bizarre tirade before spring training began. “It was a matter of pride and decency,” said Loes contemptuously.56 Loes was insulted that Mets president George Weiss did not publicly acknowledge the hurler’s sore shoulder and welcome him with open arms. “I’m no animal,” said Loes. “I’ve got feelings, too.”57 The Mets returned Loes to the Giants, who released him on March 2.

So ended Loes’ tumultuous 11-year big-league career. He expressed a desire to coach and even volunteered to return to baseball in 1963, but the player who spent the previous decade antagonizing his managers and front office had no takers. His final slate included an 80-63 record and 3.89 ERA in 1,190⅓ innings. He batted .110 on 38 hits.

Loes’ transition away from baseball was not easy. He returned to Long Island, where he remained for most of the rest of his life, and drifted away from baseball. “I was floating from job to job,” said Loes about 10 years after he left the game.58 He drove a cab, worked a lunch counter, and served as a youth counselor in a Greek organization. “I never liked stayin’ in one place too long,” he declared.59 In 1990 he was inducted into the Brooklyn Dodgers Hall of Fame at the Brooklyn Museum, and momentarily soaked up the media’s attention. If those in attendance hoped that Loes would offer sentimental words about Brooklyn and the Dodgers of the 1950s, they were sorely disappointed. “I think Brooklyn was dying at the time,” said Loes with the frankness that defined his career. “[Team owner Walter] O’Malley had foresight and [the Dodgers’ move] was a great thing for baseball.” And then he offered a morsel of romantic dreaming by adding, “Brooklyn needs a baseball team.”60

On July 15, 2010, Billy Loes died in Tucson, Arizona at the age of 80. According to his New York Times obituary, he had been suffering from diabetes for many years, and had not been in good health.61 He was survived by his wife, Irene; the two had been separated.

This biography appeared in “From Spring Training to Screen Test: Baseball Players Turned Actors“ (SABR, 2018), edited by Rob Edelman and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Loes’ player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com, and The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record. Special thanks to Bill Mortell for his assistance with genealogical research.

Notes

1Jimmy Breslin, “The Dodgers’ New Daffiness Boy,” Saturday Evening Post, August 23, 1953: 115.

2 Breslin, 116.

3 Tommy Holmes, High Homers, Low Sun Foil Pale Face Kid,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 7, 1952: 13.

4 “Flock Wants Heavier Loes,” Brooklyn Eagle, February 1, 1954: 14.

5 Breslin, 116.

6 The Sporting News, January 19, 1955: 13.

7 Jack Orr, “Has Success Spoiled Billy Loes,” Sport, June 1958: 85.

8 Tommy Holmes, “The Sudden Rise of Billy Loes,” Brooklyn Eagle, May 27, 1952: 19.

9 Dave Anderson, “Loes to Miss Next Start,” Brooklyn Eagle, April 29, 1954: 18.

10 The Sporting News, August 27, 1952: 3.

11 “Dodgers Won’t Pay for Loes’ Gift Dog,” Brooklyn Eagle, July 3, 1953: 11.

12 Arthur Daley, “Sports of the Times,” New York Times, March 4, 1956: S2.

13 Zander Hollander, “It’s Look but Don’t Touch for Scouts Tailing Loes,” New York World-Telegram and Sun, June 15, 1948.

14 “Bryant in Final on Loes No-Hitter,” Brooklyn Eagle, June 15, 1948: 15.

15 Zander Hollander, “Pro Ball Modifies Loes, But He’s Still Hot Stuff,” New York World-Telegram and Sun, July 12, 1996.

16 “Bryant Gains City P.S.A.L. Title on Brilliant One-Hitter by Loes,” Brooklyn Eagle, June 26, 1948: 7.

17 Breslin, 116.

18 Zander Hollander, “It’s Look but Don’t Touch for Scouts Tailing Loes.”

19 James Murphy, “All-Stars Leave for Washington,” Brooklyn Eagle, July 26, 1948: 13.

20 ‘Loes Stars in Debut as Semi-Pro Hurler,” Brooklyn Eagle, August 16, 1948.

21 Breslin, 116.

22 Ibid.

23 The Sporting News, February 4, 1953: 6.

24 Ben Gould, “Bonus Player Loes Faces Jump to Flock in Only One Season,” Brooklyn Eagle, April 27, 1949: 23.

25 “Dodgers Call Up Bankhead, 4 Others,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 10, 1949: 24.

26 Joe Lee, “Dodgers Lose Billy Loes to Uncle Sam,” Brooklyn Eagle, February 7, 1951: 20.

27 “Billy Loes of Dodgers Get Out of Army,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 20, 1951: 6.

28 “Loes Due for Discharge,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 16, 1951: 12.

29 The Sporting News, August 27, 1952: 3.

30 Breslin, 116.

31 “Dodger Chief Brands Loes Paternity Case ‘Blackmail,’” Brooklyn Eagle, October 20, 1952: 1.

32 Breslin, 117.

33 The Sporting News, August 27, 1952: 3.

34 Breslin, 118.

35 Game Six of the 1952 World Series, You Tube, https://youtube.com/watch?v=ry-qwiXt82w.

36 Dave Anderson, “Erskine Rates as Only Brooks Sold?? Starter,” Brooklyn Eagle, September 9, 1953: 19.

37 Tommy Holmes, “Scatter Shot at the Sports Scene,” Brooklyn Eagle,” August 24, 1953: 13.

38 “Loes to Know No Behavior Pattern,” Brooklyn Eagle, March 26, 1954: 14.

39 Harold C. Burr, “Billy Loes Is Not Alone in Indifference to Game,” Brooklyn Eagle, April 2, 1954: 2.

40 “Loes Termed ‘A Mystery’ by Flock Manager,” Brooklyn Eagle, June 21, 1954: 13.

41 Dave Anderson, “Absence of Dodgers Spirit Annoys Alston in Drive for Second Place,” Brooklyn Eagle, September 20, 1954: 19.

42 Watch the entire movie on YouTube: https://youtube.com/watch?v=ZPaIYL-Neoc.

43 “Flatbush Boy, Gaining Fame on TV, Is Still Kid at Home,’ Brooklyn Eagle, March 4, 1954: 7. In the film, the ghost of Red O’Malley, a deceased Dodgers star hurler, appears before Roogie and provides him with the bump that transforms him into the “miracle kid with the super zoom ball.” Rob Edelman adds: In the film, Red O’Malley is nothing less than saintly, and even is patronizingly referred to as the “Great O’Malley.” One has to ask: Is there any connection here to the name of the real Dodgers owner?

44 Jane Corby, “‘Duel in the Sun,’ ‘Roogie Bump’ Share Boro Paramount Bill,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 13, 1954: 12.

45 The Sporting News, January 19, 1955: 13.

46 Dave Anderson, “Weirdie Loes May Mellow With Age,” Brooklyn Eagle, December 29, 1954: 17.

47 United Press, “Billy Loes Is Baseball Gem, Dodgers Say,” Logansport (Indiana) Pharos-Tribune, January 12, 1955: 18.

48 The Sporting News, October 12, 1955: 7.

49 Orr, 94.

50 Ibid.

51 United Press International, “’Orioles’ Loes Seeks ‘Comeback’ Honors,” Austin (Minnesota) Herald, June 26, 1957: 12.

52 The Sporting News, July 17, 1957: 15.

53 The Sporting News, June 11, 1958: 11.

54 UPI, “Loes, Orioles Parting,” New York World Telegram and Sun, June 2, 1958.

55 “Orioles Give Up, Loes Headed for Minors,” New York World Telegram and Sun, March 13, 1959.

56 Milton Richman, UPI, “Loes Quits Due to Conditions,” Tyrone (Pennsylvania) Daily Herald, February 10, 1962: 8.

57 Ibid.

58 Bill Madden, UPI, “Ex-Dodger Pitcher Billy Loes, Who Once ‘Lost’ Ground Ball in the Sun, Has Found Himself.” [Article dated October 10, 1973. Player’s Hall of Fame file].

59 Ibid.

60 Michael George, “Ex-Bum Loes Says Baseball Shouldn’t Dodge Brooklyn,” New York Post, June 11, 1990.

61 Richard Goldstein, “Billy Loes, Quirky Pitcher for Dodgers, Dies at 80,” New York Times, July 27, 2010.

Full Name

William Loes

Born

December 13, 1929 at Long Island City, NY (USA)

Died

July 15, 2010 at Tucson, AZ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.