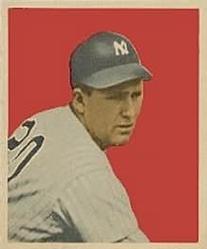

Spec Shea

In the spring of 1947, “uncertain” may have been the word that best described the New York Yankees’ prospects. The team that had dominated the American League throughout the late 1930s and the early 1940s was coming off an ignoble third-place finish in 1946, seventeen games behind— and seemingly light years removed from—the champion Boston Red Sox.

In the spring of 1947, “uncertain” may have been the word that best described the New York Yankees’ prospects. The team that had dominated the American League throughout the late 1930s and the early 1940s was coming off an ignoble third-place finish in 1946, seventeen games behind— and seemingly light years removed from—the champion Boston Red Sox.

The pitching, after twenty-game winner Spud Chandler was suspect. Joe DiMaggio and shortstop Phil Rizzuto had returned from three years of military service and turned in subpar seasons. All-Star second baseman Joe Gordon batted .210 and was traded to Cleveland for right-handed pitcher Allie Reynolds, who lost as often as he won.

Would this group of Yankees be able to rebound to challenge the Red Sox? The answer was an emphatic “yes,” with help.

Give a lion’s share of the credit to Frank “Spec” Shea, a twenty-six-year-old rookie right-hander from Naugatuck, Connecticut, who threw hard and cracked wise. Shea assembled a 14-5 record with a 3.07 earned run average for the pennant-winning Bronx Bombers, leading the league in fewest hits allowed per nine innings (6.4) and winning percentage (.737). On July 8 he became the first rookie pitcher to receive credit for a victory in the All-Star Game, working the middle three innings of the American League’s 2–1 win at Wrigley Field in Chicago.

Spec (so named as a youngster because of his freckles) capped his memorable first season by winning two decisions in the Yankees’ seven-game World Series victory over the Brooklyn Dodgers.

If there had been separate Rookie of the Year awards for each league, Shea would have been an overwhelming choice as the American League’s best freshman. Instead, he placed third in the overall balloting behind two National Leaguers, Jackie Robinson of the Dodgers and pitcher Larry Jansen of the New York Giants.

“Everything I touched turned to gold that year,” Shea recalled. “Getting credit for the win in the All-Star Game. Two victories in the World Series. How fortunate I was. It was a year you dream about. The only thing I feel bad about was I hurt my arm that year. I had no problem winning in the big leagues.”

Francis Joseph O’Shea was born in Naugatuck on Oct. 2, 1920, to Frank Lawrence O’Shea and Helen (Morris) O’Shea. His only sibling, the future Eleanor Scheiber, had arrived two years earlier.

The senior O’Shea was an aspiring pitcher, too, but after a fine playing career at Naugatuck High School, he married young and limited his pitching to semipro ball. When Frank Jr. was born, his dad vowed that he would have a big league career by proxy—the one he mapped out for his newborn son.

Young Frank was a whiz himself at Naugatuck High. In 1938 he pitched a four-hitter and hit a pair of home runs to propel the Greyhounds to a 7–0 verdict over Manchester High in Connecticut’s first state championship game. As a senior the following season, he struck out twenty-one batters in eleven innings in the state title game against Torrington.

Paul Krichell, the Yankees scout credited with discovering Lou Gehrig, added Shea to his portfolio in the winter of 1940. A story goes with it.

En route to Naugatuck to sign Shea (he had by now dropped the O’ in his name) to a Yankees contract, Krichell was stopped by a Connecticut state trooper in Westport. Asked to identify himself, he told the officer about his Yankees affiliation and said that he was heading to Naugatuck to sign a young pitcher named Frank Shea.

“Hell’s bells,” the state trooper responded. “Why didn’t you tell me that in the first place? Just follow me and I’ll lead you to him. That Shea kid is a wow and I’m a Yankee fan.”

Shea’s progression through the Yankees’ farm system was rapid—11-4 with Amsterdam, New York, of the Class C Canadian-American League in 1940, 16-10 with Norfolk, Virginia of the Class B Piedmont League in 1941, and a luckless 5-8 (despite a 3.15 ERA and 89 strikeouts in 100 innings) with Kansas City of the Class Double-A American Association in 1942. Then World War II intervened.

Shea spent three years in the Army Air Corps, and was among the thousands of GIs who went ashore in Normandy just days after D-Day. The oldest of his three children, also named Frank, recalled hearing a story from his dad about being injured in an explosion during the war.

“He was carrying two cans of gasoline and a sniper’s bullet hit one of the cannisters,” young Frank related. Scorched virtually from head to toe, Shea was a hospital case for months.

“No Purple Heart, though,” he said years later, “because it wasn’t enemy action. I always wondered, though, if they called it friendly action.”

Discharged from the Army too late to return to Organized Ball in 1945, the former Sergeant Shea returned home to pitch for the semipro Waterbury Brasscos. Talk about timing. The Brasscos had an exhibition date scheduled with the Yankees, and Spec merely shut them out, 1–0.

That performance earned him an invitation to spring training with the Yankees in 1946. Alas, Shea required an emergency appendectomy during the team’s trip to Panama, and he was sidelined for a couple of months. His pitching that summer, although outstanding, was with the Oakland Oaks of the Pacific Coast League under manager Casey Stengel.

Shea won fifteen of twenty decisions for the second-place Oaks, struck out 124 and compiled a brilliant 1.66 ERA, second in the league behind San Francisco’s Larry Jansen, at 1.57.

The following spring in St. Petersburg, Florida, a healthy Shea impressed new Yankees manager Bucky Harris, and along with twenty-year-old prospect Don Johnson, was a candidate for a spot in the club’s starting rotation.

Dan Parker, the New York Mirror sports columnist who had watched Shea’s father pitch in high school, told Harris that if he liked Spec, he should have seen his dad. “I’ll settle for him,” said Bucky. “I wish I had a dozen like him. He’s my type of pitcher. I don’t see how he can miss.”

The six-foot, 195-pound Shea made his Major League debut on April 19, 1947, pitching two innings of scoreless relief in a 4–2 loss at Griffith Stadium. He made his first start five days later, against the defending champion Red Sox at Yankee Stadium. He allowed just three singles in nine innings, but wound up on the short end of a 1–0 score. The lone Red Sox run crossed the plate in the fifth on a pair of walks (Shea walked seven in the game), a force out and Sam Mele’s scoring fly ball.

If a well-pitched defeat can be considered a portent, that was the case here. Mixing fastballs with curves and sliders, over his next eight starts Shea reeled off seven straight victories and a no-decision, including a pair of shutouts against Detroit Tigers ace Hal Newhouser. After a 3–2 loss to the Chicago White Sox in eleven innings, he won four more, highlighted by a three-hit, 3–0 decision over the Cleveland Indians. Shea entered the All-Star break with a luminous 11-2 record, twelve complete games and a 1.91 ERA.

Yankees announcer Mel Allen dubbed him The Naugatuck Nugget, a nickname that endured until the end. His Naugatuck neighbors and admirers, delighted by his early successes, turned out en masse to honor their native son on Frank “Spec” Shea Day at Yankee Stadium on June 22. Heading the delegation from his hometown was his dad who, in his son’s achievements, saw the fulfillment of his own aspirations.

The crowd of 53,765 included thousands from Connecticut who had purchased tickets weeks in advance in the hope of seeing Shea pitch. (He didn’t.) In pregame ceremonies, the Borough of Naugatuck’s warden, Harry L. Carter, presented Shea with a 1947 maroon Hudson, replete with the Connecticut license plate SPEC.

“I grew up as a Yankee fan,” Shea said. “My father took me down to the Stadium when I was a kid, and this was when you could go on the field after the game. I used to run out to the mound and pretend I was pitching. ‘Someday,’ I’d say, “I’m going to pitch here.”

And so he did. But for the remainder of July and all of August, Shea pitched neither well nor often, due to a nagging neck injury that restricted him to a handful of appearances. He rebounded in September by winning three of four decisions, including a four-hit, 3–1 triumph over the White Sox on September 18.

In the 1947 World Series, Shea proved more than a match for the Dodgers by winning two games. He captured the opener at Yankee Stadium by a 5–3 score, allowing just one run and two hits in five innings before departing for a pinch-hitter.

In Game Five, two days after Shea celebrated his twenty-seventh birthday—the right-hander gave the Yankees a 3–2 Series lead by stopping the Dodgers, 2–1, on a four-hitter at Ebbets Field. At bat he contributed a double and single, the latter driving in New York’s first run in the fourth inning. In a fitting coda, Shea fired a third strike past the previous day’s hero, Cookie Lavagetto, for the final out.

After the Dodgers won the sixth game, 8–6, to square the Series once again, the Yankees’ mercurial president, Larry MacPhail, offered a one-thousand-dollar bonus to any Yankees pitcher who would start Game Seven.

Shea accepted the offer, but he departed in the second inning after allowing one run and three straight hits. And, “You know, I never got that thousand dollars,” Frank Shea recalled his father telling him on several occasions. But the Yankees rallied to prevail, 5–2, to gain their eleventh world championship.

Likable and loquacious, the pitcher enjoyed a special friendship with DiMaggio, a man who could be aloof. “He used to buy me breakfast every day at the hotel. He’d never let me pay,” Shea said. “I never treated DiMaggio like God. He was an everyday guy as far as I was concerned.”

Shea provided frequent livery service for the Yankee Clipper during their years together in New York. He recalled one occasion when DiMaggio was opening his mail during their drive to Yankee Stadium. He opened an envelope. A check appeared. He opened another envelope. Another check. “By the time we got to the ballpark, he had $12,000 in endorsements,” Spec said.

Never again did Shea approach his rookie accomplishments. He pitched reasonably well in 1948, but a lack of run support contributed to a 9-10 record despite his leading the American League a second time in the fewest hits allowed per nine innings. His ERA was a respectable 3.41.

The arm and neck maladies that kept Shea on the sidelines for several weeks late in the 1947 season forced his return to the Minor Leagues for a portion of 1949 and all of 1950. In ’49, he was 1-1 with the parent club, 0-3 in five appearances with Newark of the International League. With Kansas City of the American Association in 1950, the results also were less than encouraging—6-11 with a 6.28 ERA.

Rejoining the Yankees in 1951 as a reliever and spot-starter, Shea contributed a 5-5 record, a pair of shutouts, and a 4.33 ERA to the Bombers’ drive to another American League pennant. But he wasn’t called upon in the World Series when the Yankees bested the Giants in six games.

With an established Big Three of Reynolds, Vic Raschi, and Eddie Lopat, as well as Whitey Ford waiting in the wings, Shea was deemed expendable. On May 3, 1952, he accompanied outfielder Jackie Jensen to the Washington Senators in a six-player trade that brought outfielder Irv Noren to New York. Shea was not in the least disappointed.

“Hey, that trade reunited me with Bucky Harris, and he gave me a chance to pitch,” Shea said. “The owner, Clark Griffith, who was a grand guy, told me I wouldn’t be making any World Series money here and he handed me a $2,500 check when I arrived to make me feel welcome.”

With fifth-place Senators teams, Shea proved a solid No. 2 starter behind another ex-Yankee, Bob Porterfield, turning in records of 11-7 in 1952 and 12-7 in 1953. He contributed to the Yankees’ pennant in 1953 by defeating runner-up Cleveland four times without a loss.

“He’s still quite a funny guy, but he’s more serious now than ever,” Harris told the Washington Star’s Morris Siegel. “And Frank is a smarter pitcher now. He sets you up for a pitch. And what a battler he is. He’ll fight you right down to the last pitch of the ballgame. And in those tough spots, he’s always putting a little something extra on the pitch. I wish the Yankees or any other club would give up on a number of guys like him. I’ll find a place for them.”

When his eight-year Major League career was nearing its end in 1955 (lifetime record: 56 wins, 46 losses, 3.80 ERA), Clark Griffith asked Shea to be the Senators’ pitching coach the following season. Shea was receptive. But Griffith died that fall, and his heirs had other plans.

So Spec and his wife, Genevieve (Martino) Shea, whom he’d married in 1949, and their young sons, Frank and John, settled in Naugatuck. A third child, daughter Barbara, was born a decade later. Shea eventually became the borough’s superintendent of parks and recreation, a position he held for twenty years until his retirement in 1989.

A gifted storyteller, he was a welcome guest on the banquet circuit, especially at the Connecticut Sports Writers’ Alliance’s annual Gold Key Dinner. He was among the three honorees at the group’s 1962 banquet. He also returned to Yankee Stadium each summer to wear the pinstripes for the annual Old Timers Day. (Writer to Shea: “Ready to go nine today?” Shea to writer: “Yeah, nine pitches.”)

Accompanied by other retired Major Leaguers such as Ralph Branca, Willard Marshall, and Sal Yvars, Shea participated in charity golf tournaments throughout Connecticut and New York’s Westchester County, helping to raise funds for local nonprofits.

He also devoted considerable time to the Baseball Assistance Team (B.A.T.), the organization founded by retired Major League catcher and broadcaster Joe Garagiola to help indigent former players and other baseball people in need.

In the early 1980s the Naugatuck Nugget had one additional brush with fame. The telephone rang in the Shea household one day, and Spec asked his daughter to answer it. “May I ask who’s calling, please,” said Barbara Shea, then nineteen years old. “It was Robert Redford. I think he said ‘Bob Redford.’”

Indeed, Robert Redford was preparing for the role of Roy Hobbs in the acclaimed 1984 film, The Natural, and he asked Spec Shea to teach him how to pitch and hit 1930s style. “I don’t want to embarrass myself,” Redford told the retired pitcher.

So, on at least one Sunday, perhaps on a few occasions (stories differ), Shea provided the rudiments of pitching and hitting to the Oscar-winning Hollywood actor and director at Breen Field in Naugatuck.

“People were walking by, saying, ‘Is that Robert Redford?’” Frank the son remembered.

“It was supposed to be a big secret, but the word got out,” Barbara said.

Shea “was just a big, happy guy,” said Barry Lockwood, an officer in the Naugatuck Hall of Fame, which included the old pitcher among its original inductees in 1972. “Spec was one of the people this town was noted for. When he was on top of his game, no one was his equal.”

John Hassenfeldt, a boyhood friend, remembered Shea as a guy who was “always willing to talk to everybody. And he did a lot to help the kids of this town.”

Frank “Spec” Shea died on July 19, 2002, four weeks after heart valve replacement surgery at Yale-New Haven Hospital. He was eighty-one years old.

This biography is included in the book “Bridging Two Dynasties: The 1947 New York Yankees” (University of Nebraska Press, 2013), edited by Lyle Spatz. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Sources

Cramer, Richard Ben. Joe DiMaggio: The Hero’s Life. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000.

Daniel, Dan. “Shea Seeks 20-Game Circle with New Fadeaway

Pitch,” New York World-Telegram, March 5, 1948.

Daniel, Dan. “Hats Off…!,” Sporting News, June 18, 1947.

Goldstein, Richard. “Frank Shea, 81, Yankee Pitcher in ’47 Series,” New York Times, July 23, 2002.

Harrison, Don. “Growing Up with a Naugatuck Legend,” Naugatuck Patch, July 28, 2011.

Harrison, Don. “Loquacious Shea was a Wit,” Fairfield Citizen-News, July 26, 2002.

Harrison, Don. “Memories of a Memorable Yankee Year,” The New York Times, October 23, 1995.

Harrison, Don. “Shea: Page Was the Best,” Waterbury Republican, April 27, 1980.

Harrison, Don. “Spec’s Era Tamer,” Waterbury Republican, May 23, 1976.

Heinz, W.C. “Harris Grooms Shea for the Series,” New York Sun, September 17, 1947.

Palladino, Joe. “’Spec’ Shea, Yanks’ Naugatuck Nugget, Dies,” Waterbury Republican-American, July 20, 2002.

Parker, Dan. “Timing Made Shea Day Anti-Climax,” New York Mirror, June 23, 1947.

Parker, Dan. “Shea of Yanks Making Dad’s Dream Come True,” New York Mirror, March 24, 1947.

Povich, Shirley. “Shea of Nats is Newsom Character With Class,” Washington Post, May 25, 1952.

Povich, Shirley. “This Morning,” Washington Post, June 30, 1947. Scannell, Ed. “Connecticut Yankee.” Worcester Telegram & Gazette, 1948 (no month or day indicated).

Siegel, Morris. “Shea as Senator Back in Freshman Form,” Sporting News, July 30, 1952.

Wedge, Will. “Shea to Rest Damaged Elbow,” New York Sun, July 24, 1947.

Special thanks to Frank Shea and Joe Palladino.

Telephone conversation between Thomas Bourke and Frank Shea’s son, Frank, on December 13, 2011.

Full Name

Francis Joseph Shea

Born

October 2, 1920 at Naugatuck, CT (USA)

Died

July 19, 2002 at New Haven, CT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.