Frank Killen

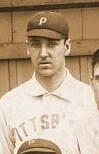

“Frank Killen is certainly a natural born pitcher,” opined sportswriter John M. Roche in Sporting Life in 1892 as the burly 6-foot-1, 200-pound southpaw was preparing for his first full season in the big leagues. “He is well built, young and possessed of all the attributes which go to make up a winning pitcher.”1 That season Killen won 29 games for the lowly Washington Senators of the National League before being dealt to his hometown Pittsburgh Pirates in a stunning trade in the offseason. Known as much for his speed and curves as his stubbornness and temper, Killen paced the NL in victories in two of the next four seasons. For a brief time, Killen’s name was uttered with the likes of nineteenth-century stalwarts Amos Rusie, Kid Nichols, and Cy Young as the best hurlers in the game, but severe injuries, overwork, and a general combative disposition eventually took their toll on the left-hander, who posted a 164-131 record in parts of 10 seasons (1891-1900).

“Frank Killen is certainly a natural born pitcher,” opined sportswriter John M. Roche in Sporting Life in 1892 as the burly 6-foot-1, 200-pound southpaw was preparing for his first full season in the big leagues. “He is well built, young and possessed of all the attributes which go to make up a winning pitcher.”1 That season Killen won 29 games for the lowly Washington Senators of the National League before being dealt to his hometown Pittsburgh Pirates in a stunning trade in the offseason. Known as much for his speed and curves as his stubbornness and temper, Killen paced the NL in victories in two of the next four seasons. For a brief time, Killen’s name was uttered with the likes of nineteenth-century stalwarts Amos Rusie, Kid Nichols, and Cy Young as the best hurlers in the game, but severe injuries, overwork, and a general combative disposition eventually took their toll on the left-hander, who posted a 164-131 record in parts of 10 seasons (1891-1900).

Frank Bissell Killen was born on November 30, 1870, in Pittsburgh.2 His father, John Killen, was the son of Irish immigrants, and worked in the iron and later steel factories of the burgeoning industrial city situated on the confluence of three rivers, the Allegheny and Monongahela, which merge to form the mighty Ohio. Mother Mary T. (Miller) Killen was a stout-hearted woman who raised no fewer than nine children (five boys and four girls), born between about 1847 and 1870. According to the Pittsburgh Daily Post, Killen “played ball since boyhood,” braving the soot and pollution from the coke blast furnaces, steel mills, glass works, and burning coal that often covered the entire city in a dark, pungent haze, leading to the city’s unflattering moniker, the Smoky City.3 Longtime Pittsburgh sportswriter John M. Gruber wrote that as a teenager Killen had “no sense of humor [and was] rather somber and serious in all he said and did.”4 Always big for his size, young Frank primarily played catcher until managers quickly realized that his powerful left arm was more valuable in the pitcher’s box.

Killen’s first foray into professional baseball came in 1889 when he tried out for the Dayton (Ohio) Reds of the Tri-State League. He hurled in an exhibition game, but was “sent home without having been given a trial” when the club signed another promising left-hander, Charles Dewald.5 The teenage Killen returned to Pittsburgh and donned the uniform of the Braddock Blues in the Allegheny County League. His performance against the Pirates in a late-season exhibition game caught the attention of team brass, who monitored the youngster’s development in the coming years.

The next season, 1890, Killen signed his first professional contract, with Manistee in the Michigan State League, during the infancy of the minor leagues in Organized Baseball. While the National Association, founded in 1871, is generally considered the first professional baseball league (the predecessor of the National League, which was founded in 1876), the minor leagues trace their roots back to 1883 when the NL, the American Association, and the Northwestern League signed a contract, the National Agreement, that regulated everything from player salaries and league territories to disputes. With its lower salaries, the Northwestern League became the first minor league, while the NL and AA were considered the “majors.” By 1890 there were 29 minor leagues, the majority of which were spread from the Northeast to the Upper Midwest. All of the leagues were considered independent; the formal classification of minor leagues began in 1902.6

Professional baseball players have always been dreamers, willing to follow their passions and endure hardship and failure while being tossed by the whims of fate to fulfill their fantasies. They also needed some luck and plenty of perseverance. Killen had all of that and more. He made an immediate splash with Manistee, starting every game in the team’s existence and winning 16 of 24 contests before the league folded in mid-June. “[Killen] was fast enough for any league,” gushed George Blackstone of the Muskegon team, “and no doubt had as much speed, if not more, than any other left-hander in the country.”7 Financial insecurity of minor teams and leagues was a hallmark of Organized Baseball at the time. Killen was quickly scooped up by Grand Rapids of the International Association, and went 3-1, including a one-hit shutout; but this league folded too, just weeks later. Killen landed with his third team in just over four weeks, Minneapolis of the Western Association, the most stable and prosperous of all the minor leagues. Described as being in “grand form,” Killen posted a 9-6 record as the Millers challenged the Kansas City Blues for the league crown, finishing as runners-up even though they won more games (80 to 78) but also played six more.8 On September 12 Killen hurled the game of his life, coming within one error of a perfect game and striking out 10 against the Sioux City Cornhuskers.

“Killen is nothing more than a big boy, but he has plenty of speed and a good head,” opined Sporting Life in 1891. “[T]here is every reason to believe, [he] will be up front (in the major leagues) in a year or so.”9 Killen was indeed a hot commodity. Chris von der Ahe, the brash German-born owner of the St. Louis Browns of the American Association, tempted him with a “big offer” to break his contract and jump to his squad.10 Killen might have rued his decision to stick with the Millers, who subsequently disbanded on August 20. Killen (18-13 and 275⅔ innings) quickly signed on with the Milwaukee Brewers, who had left the Western Association to replace Cincinnati in the AA. Killen’s odyssey to the big leagues, albeit via a circuitous and meandering route, was complete, yet far from stable. Killen did “clever work” with the Brewers (7-4, 1.68 ERA), completing all 11 starts. As SABR member Stew Thornley noted, Killen was involved in the first big-league game in the history of Minneapolis, on October 2, when for financial reasons Milwaukee and the Columbus Senators transferred their last series of the season to Minnesota.11 When cold weather canceled two games scheduled for the next day, Killen’s six-hit shutout proved to be the last major-league game in the Twin Cities until the Minnesota Twins played their home opener on April 21, 1961, after their relocation from Washington.

In the offseason Killen signed a contract reportedly worth $3,000 to remain with Milwaukee for the 1892 season, but there were rumblings about the club’s financial insolvency. Pittsburgh Pirates president William Temple publicly announced his willingness to sign the hurler but not if he was still under contract. “It is our aim to give the people of Pittsburg as good a team as we can get together,” he promised.12 Since its founding in 1882, the American Association had battled the NL over its claim as a legitimate “major league.” The upstart AA, often referred to as the “Beer and Whiskey League,” with teams located primarily in what is now the greater Midwest, rejected the NL’s staid, gentlemanly approach to baseball by playing games on Sunday and even selling alcohol at games. More troublesome was the AA’s tendency to raid the rosters of NL teams despite agreements to refrain from the practice. “If there is anything your neighbor has that you want, snatch it,” wrote the Pittsburgh Dispatch in reference to the instability that contract jumpers, enticed by large salaries, had wrought upon both leagues.13 A turning point in major-league baseball occurred in December 1891 in what became known as the Indianapolis peace deal, whereby the two leagues merged. Four AA teams (Baltimore, Louisville, St. Louis, and Washington) joined the NL to form a 12-team league. Players from the four disbanded AA teams were assigned to NL clubs. “Unfortunately for the players, the funeral of Personal Desires occurred at Indianapolis,” wrote Sporting Life about players who objected to their transfer, as well as teams that were dissatisfied with their assigned players. “There were no pallbearers and few mourners.”14

Killen and 11 other AA players were assigned to Washington, which changed its name from the Statesmen to Senators to inaugurate a new chapter in its history.15 Almost immediately Killen began trading jabs in the press with manager Billy Barnie, claiming that Washington’s contract offer was lower than the one he had signed with Milwaukee and which was supposedly valid under the rules of the peace settlement. Killen, like all major-league players, quickly learned that the merger depressed salaries. Praised as “one of the most promising pitchers in the country” and the “only reliable twirler on the team,” Killen (29-26) was the lone bright spot on the 10th-place Senators (58-93), winning half of their games. Six hurlers won at least 30 games that season in the NL, including the aforementioned Young, Rusie and Nichols. Killen completed 46 of 52 starts among his 60 games while logging 459⅔ innings, third most in the circuit, but well behind Chicago’s Bill Hutchinson’s hard-to-fathom 622. The hard-throwing Killen was hailed as “a great general while officiating in the box [whose] deceptive curves have time and again proved very puzzling.”16

By all accounts, Killen had an explosive and confrontational personality, and had difficulty controlling his emotions on and off the diamond throughout his career. The “grave objection to Killen is his temper,” opined Sporting Life. “He is as obstinate as a mule.”17 He supposedly threatened to quit the Senators in May when manager Arthur Irwin (who had replaced Barnie) briefly suspended him for concealing a thumb injury incurred from fighting with a teammate in a pool hall.18 Killen had a tendency to sulk when he pitched poorly, and lambasted teammates for poor defensive play or the lack of runs. He was especially sensitive to criticism, no matter what the source. Stories abound about how he stuffed his ears with cotton to drown out heckling from the stands and opponents’ dugouts. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch described Killen disparagingly as “one of the characters of the profession [who is] great when his team is in the lead, but goes to pieces when his support is bad or his opponents make a batting rally.”19

After just one season, Killen had worn out his welcome with the Senators. Trade rumors swirled as soon as the season ended, but few sportswriters (and fans) probably thought the struggling club would jettison its best player, who threatened to sit out the season unless the Senators met his salary demands. The announcement of Killen’s trade the following spring, on March 21, to the Pittsburgh Pirates in exchange for catcher Duke Farrell and $1,500 struck “like a bombshell,” wrote John H. Roche in Sporting Life.20 The Pirates had “dreamed of Killen for two seasons,” reported the paper, which also cautioned that all left-handers are inherently erratic, hinting at the possibility that Killen might not be as good as advertised. Southpaws were a rarity in the majors at the time. Of the 26 pitchers who won at least 16 games in 1892, Killen was the only left-hander; a year earlier lefties accounted for only 24 wins all season in the NL, 20 of them by Duke Esper.

Concerns about Killen’s effectiveness were understandable. A major rule change affecting pitchers took place in 1893. The pitcher’s box (a 5½-by-4-foot rectangle whose rear line was 55½ feet from the center of home plate) was replaced with a pitcher’s rubber, located 60 feet 6 inches from home plate.21 [Pitchers still threw from a flat surface; gradually elevated mounds were introduced and regulated by 1904.] Speedballer Amos “The Hoosier Thunderbolt” Rusie, who had fanned more than 300 batters each season from 1891 to 1893, is often cited as the reason for the rule change, which many thought would benefit hitters and adversely affect hard throwers like Rusie and Killen. The distance the ball had to travel from pitcher to batter led to an “offensive explosion,” with runs per game increasing from 10.2 to 13.1 and batting averages from .245 to .280, while strikeouts per game dropped from just over 6.5 to 4.3. Some pitchers suffered under the new pitching distance, most notably Hutchinson, who went from 36 wins and 314 strikeouts in 1892 to 16 and 84 respectively in 1893.

Killen seemed like the missing piece for the Pirates to challenge for the pennant. Just three years removed from a 23-113 debacle in 1890, the Pirates were coming off their first winning record since 1886, when they were known as the Alleghenys, a charter member of the American Association, before they jumped to the NL in 1887. Killen quickly put to rest any fear that he would fail to adapt to the new pitching changes. He blew through the opposition, posting a league-best 36 victories against just 14 defeats. No left-hander in NL history has won as many games since. The only hurler in Pirates history to record more victories is Ed Morris, who won 39 and 41 in 1885 and 1886 respectively, when the team was still in the AA. Killen also set a club mark with 12 straight victories (later broken by Deacon Phillippe’s 13 straight in 1910). Sporting Life praised Killen’s “deceptive motion of his body similar and superior to one successfully used by (Pud) Galvin,” the former Buffalo Bisons and Pirates star who had retired the previous season with 365 victories.22 En route to completing 38 of 48 starts and logging 415 innings, Killen took revenge on Washington, beating them five times, as Pittsburgh surprised baseball by finishing in second place (81-48), five games behind the Boston Beaneaters. “[Killen] must be given much of the credit for the good standing of the club,” mused one writer.23

Killen’s pitching evoked strong protests from opponents. “Players generally denounce Frank Killen’s delivery as illegal because he will inch up on the batsman,” reported Sporting Life. “He did the same thing in the pitcher’s box under the old rule.”24 Games at this time were refereed by a sole umpire who had a paramount task of determining if a pitcher’s foot was on the slab as required. Killen, perhaps more than any other pitcher of his generation, was regularly charged with “stealing a foot of ground,” an accusation he never escaped.25

While Killen’s success made him a sports celebrity in Pittsburgh, it also emboldened him in contract negotiations with the Pirates. He once again threatened to sit out the season if the club did not meet his salary demands. The Pirates “caused quite an excitement” by announcing a proposed trade sending the hard-nosed hurler to St. Louis for another southpaw, Ted Breitenstein, who had burst on the scene by winning 19 games and leading the league in ERA. Killen finally affixed his name on the dotted line, but the 1894 season did not unfold as expected, as the burly hurler struggled early. “[Killen] uses less head work than any other successful pitcher,” criticized one sportswriter, “and batters who are cool and can wait on him never will be troubled by an inability to hit the ball.”26 In early July the Pirates suspended Killen for two days because of “poor work in the box.”27 On July 26 Killen’s season came crashing down when a screeching liner hit by George Tebeau of the Cleveland Spiders broke the pitcher’s left wrist. Less than four weeks later, the Pittsburgh Post Gazette reported that the Pirates were threatening to suspend the pitcher for not “taking good care of himself” and not healing fast enough.28 Ultimately Killen resolved his differences with manager Al Buckenberger, and agreed to return in mid-September, by which time catcher Connie Mack had become the new skipper with the Pirates struggling to play .500 ball.

Killen was determined to prove that his injury-filled campaign and 14-11 record were an aberration, but the 1895 season swiftly devolved into a nightmare. An early-season hand injury raised concerns that the 24-year-old hurler was washed up. “If [Killen] is played out as a pitcher, the sooner we find out the better,” said Mack.29 Killen seemed frustrated by his erratic pitching and fought with teammates. Mack, once described as Killen’s good friend, was exasperated with the hurler, prompting one paper to suggest that he is “tired of sticking up for Killen.”30 On June 8 Killen was involved in an ugly incident that almost ended his career. In a tense game against the New York Giants at the Polo Grounds, Parke Wilson slid aggressively into home plate, spiking Killen in the ankle. Reports of the ensuing melee differ; according to the Pittsburgh Daily Post, Killen “resented the rough treatment” and retaliated;31 Sporting Life claimed that Killen deliberately kicked Wilson, deeming the act a “disgraceful and cowardly [assault].”32 The spiking left Killen with a gaping gash, which the Post later described as a “flesh wound, the bone not being affected.”33 But the injury turned out to be much more serious. It soon became infected and filled with pus. Killen contracted blood poisoning and was subsequently hospitalized, missed the rest of the season, and was confined to crutches well into the offseason.

With a mediocre 19-16 record since he won 36 games in 1893, Killen was no longer considered one of the top pitchers in baseball. Teammate Pink Hawley, winner of 31 games for the seventh-place Pirates in 1894, had assumed the mantle of staff ace. Perhaps humbled by the previous two campaigns, Killen signed his contract without a squabble, and reported to Hot Springs, Arkansas, a popular resort and spa town renowned for its mineral baths, to get in shape for the coming season. “Mack’s faith in Killen has never been shaken,” opined the Pittsburgh Press, seemingly confident that the once-dangerous pitcher could bounce back.34 When Killen won his first two starts of the season, yielding just five earned runs, the Pittsburgh Daily Post gushed that he had “returned to his 1893 form when he was the king bee among pitchers. He has speed to throw away, and curves and shoots to pawn.”35 Despite a sore thumb, Killen had won 10 games by the end of May. “Mack has made a new man out of Killen,” praised the Press, which noted that Killen seemed less bothered by hecklers.36 The 25-year-old southpaw overcame a sprained leg in June to emerge surprisingly as the league’s best pitcher. His 30 victories tied Boston’s Kid Nichols for the league’s lead. He also paced the circuit in starts (50), complete games (44), shutouts (5), and innings (432⅓), while losing just 18 times for the sixth-place Pirates (66-63).

Killen might have paid less attention to hecklers 1896, but he didn’t lose any of his on-the-field aggression. In a game against Cincinnati at League Park on July 31, Killen charged home plate to argue with umpire Bud Lilly, who had changed his call on Eddie Burke’s fly down the left-field line from foul to hit. According to the Pittsburgh Daily Post, Lilly “let go at” Killen, apparently under the impression that the pitcher would strike him. Killen retaliated by landing “a couple of blows on (Lally’s) face” before a riot erupted with players, spectators, and police rushing onto the field.37 When order was finally restored, Killen was under arrest and escorted to the local police station. Killen was ultimately fined $25 while team owner William Kerr publicly condemned the umpire for provoking the incident.38

Known as a good hitter throughout his career, Killen batted .241 on 241 hits, including 11 home runs and 17 triples. “Some people think that he can land on the ball with more force than any other player in the country,” opined Sporting Life in 1896. He was supposedly the first left-hander to knock the ball over the left-field fence at Exposition Park in Kansas City, in 1890;39 and he knocked two of the 11 balls that cleared the right-field fence in the history of Pittsburgh’s Exposition Field, where the Pirates played from 1891 to 1909 before moving into Forbes Field.40

Killen dropped to 17-23 in 1897, though tied for the league lead in complete games (38 in 41 starts) and finished sixth in innings (337⅓) while the Pirates had their first losing season (60-71) since 1891. Killen might have suffered from the implementation of new balk rules, which the Pittsburgh Post Gazette claimed targeted Killen specifically;41 the southpaw also probably missed the calming advice of Mack, who had become part-owner and manager of the Milwaukee Brewers (Western League). On June 19 Killen defeated Baltimore 7-1 and ended Willie Keeler’s record-setting 45-game hitting streak.42 Killen and co-ace Pink Hawley feuded much of the season, and were both suspended briefly in September. “[Killen] did not exactly stand well with the club,” suggested Sporting Life.43

Killen’s days on the Pirates squad seemed numbered even after his rival Hawley was shipped in the offseason to St. Louis in exchange for right-hander Red Ehret and cash. Killen clashed with new skipper Bill Watkins, who reportedly claimed that Killen was “entirely too lazy ever to make a winning pitcher.”44 Killen countered by calling the authoritarian Watkins a “regular maniac on the bench when his men fail to play exactly as ordered.”45 Described as “several notches below the height of an ace,” Killen (10-11) lost the battle with his skipper and was unceremoniously released on August 1. Less than 10 days later he was signed by Washington, for whom he went 6-9.

The next five years (1899-1903) must have been trying ones for Killen, who played with no fewer than eight different teams in Organized Baseball, in addition to numerous semipro clubs, in search of one last shot on the big stage. After splitting 14 decisions for Washington and the Boston Beaneaters in 1899, Killen won his final three big-league games for the Chicago Orphans (later known as the Cubs) in 1900, coincidentally all against the Pirates. Chicago sportswriter W.A. Phelon wrote Killen’s epitaph of sorts even before the husky lefthander donned a Cubs uniform: “Killen has pitched good ball, but his time … has passed.”46 In parts of 10 seasons in the majors, Killen went 164-131, completed 253 of 300 starts, and logged 2,511⅓ innings.

Out of the majors before he was 30 years old, Killen posted a combined 39-34 record with five different clubs in the minors through 1903. He had a last hurrah in 1902, posting an impressive 16-6 record for the Indianapolis Indians, coincidentally skippered by his former nemesis Bill Watkins, who guided the club to the American Association title. Thereafter Killen continued to play semipro ball in Pittsburgh, and also umpired in several professional and semipro leagues, including the American Association and the Central League. He apparently lost none of his grit as an ump. According to one report, he was assaulted after a game in Minneapolis, but struck his assailants with his spikes, gashing one of them badly.47 Throughout his career in baseball, Killen kept his own counsel and was unapologetic in words and actions. In 1905 he managed the Class C Sharon Steels (Ohio-Pennsylvania League) and occasionally took the mound. By 1910, however, Killen’s active connection to baseball was over.

A Pittsburgher at heart, Killen spent most of his adult life on the North Side, not far from Exposition Park, and where Three Rivers Stadium and PNC Park would later be built. That area was an independent municipality, Allegheny, until it was annexed by Pittsburgh in 1907. On November 24, 1897, Killen married Sarah Elizabeth Hutchinson of Sewickley, a borough about 12 miles northwest of Pittsburgh. They had three children, Mildred, Frank, and Margaret. During the offseason, Killen occasionally went on barnstorming tours and pitched in exhibition games in October. After retiring from baseball, Killen worked for a short time as a detective at a railroad before settling at 1318 Federal St., where he had purchased a building with a small hotel and storefront that served as a cigar store and tavern at times.

In 1939 Pittsburgh sportswriter James L. Long named Killen as the number-one pitcher on the all-time major-league team of players born in the Steel City.48 Later that year, on December 3, Killen was found dead, slumped over in his car in a roadside ditch. According to his death certificate, he had died from a heart attack. He was 69 years old. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette noted in its obituary that the ex-big leaguer bore a remarkable resemblance to former US President Warren G. Harding.49 Killen was buried at Allegheny County Memorial Park, in Allison Park.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Killen’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com, The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record, and Ancestry.com.

Notes

1 Sporting Life, April 30, 1892: 13.

2 A short digression about the letter -h in Pittsburgh. Throughout the early nineteenth century, the city’s name was spelled both Pittsburg and Pittsburgh, although the latter was the much more dominant form and gradually became the accepted spelling. In an attempt to standardize the spelling of cities, the United States Board of Geographical Names officially changed the name of the city to Pittsburg in 1891; the German suffix -burg was much more common in the US than the Scottish -burgh (which is pronounced in Scotland as “borough”). Many Pittsburghers were aghast at the incursion of the federal government into local affairs, and boycotted the change. In 1911 the name was officially changed back to Pittsburgh after two decades of protest and general refusal to adopt the spelling. For the sake of this essay, the author used the spelling of the city as it appeared in print at the time.

3 “Baseball Chatter,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, August 1, 1897: 7.

4 John M. Gruber, “Southpaw Frank Killen Made Mark for Pirates Pitchers to Shoot At by Winning 36 Games in One Year,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, June 29, 1924: 28.

5 “Sport Gossip. Pitching Material in Big Demand by the Various League Clubs for 1893,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, January 8, 1893: 16.

6 John Cronin, “Truth in the Minor League Classification Structure: The Case for the Reclassification of the Minors,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Spring 2013.

7 Gruber.

8 Sporting Life, September 13, 1890: 7.

9 Sporting Life, March 21, 1891: 6.

10 Ibid.

11 Stew Thornley, “Minnesota’s First Professional Game,” stewthornley.net/october1891.html.

12 Sporting Life, November 28, 1891: 10.

13 “General Sporting News,” Pittsburgh Dispatch, October 8, 1891: 8.

14 Sporting Life, January 9, 1892: 2.

15 For the complete list of players transferred to NL clubs, see “Assigning the Players,” Washington Evening Star, January 2, 1892: 2.

16 Sporting Life, January 16, 1892: 11.

17 Sporting Life, March 25, 1893: 15.

18 Ibid.

19 “On the diamond,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 11, 1894: 8.

20 Sporting Life, March 25, 1993: 15.

21 Eric Miklich, “The Pitcher’s Area,” 19C Base Ball, 19cbaseball.com/field-8.html.

22 Sporting Life, June 17, 1893: 2.

23 Sporting Life, October 7, 1893: 4.

24 Sporting Life, September 9, 1893: 2.

25 Sporting Life, September 9, 1893: 3.

26 Sporting Life, April 21, 1894: 6.

27 “Killen Can’t Pitch,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 13, 1894: 6.

28 “Colcolough Released,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 21, 1894: 6.

29 Sporting Life, June 8, 1895: 8.

30 Ibid.

31 “Beat the Giants Again,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, June 9, 1895: 6.

32 Sporting Life, June 15, 1895: 10

33 “No Game Today,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, June 21, 1895: 6.

34 “Frank Killen Signed,” Pittsburgh Press, February 2, 1896: 3.

35 “Frank Killen on the Rubber,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, April 23, 1896: 6.

36 “Late Gossip of the Game,” Pittsburgh Press, June 10, 1896: 5.

37 “Policemen on the Ground,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, August 1, 1896: 6.

38 Sporting Life, August 8, 1996: 5 and 11.

39 Sporting Life, August 9, 1890: 4.

40 Gruber.

41 “Howling for Help,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, February 1, 1897: 6.

42 Keeler hit safely in his last game of the 1896 season, and the first 44 games of the 1897 season. Pete Rose tied Keeler’s single-season 44-game hitting streak in 1978.

43 Sporting Life, November 20, 1897: 9.

44 Sporting Life, September 10, 1898: 5.

45 Ibid.

46 Sporting Life, January 27, 2000: 4.

47 The Sporting News, September 10, 1904.

48 James J. Long, “All-Time Teams,” Pittsburgh Press, February 3, 1939: 35.

49 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, December 8, 1939: 21.

Full Name

Frank Bissell Killen

Born

November 30, 1870 at Pittsburgh, PA (USA)

Died

December 3, 1939 at Pittsburgh, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.