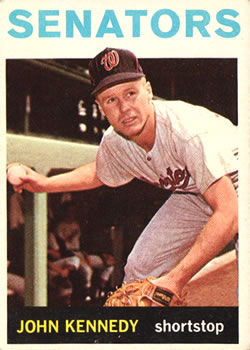

John Kennedy

John Edward Kennedy was born in Chicago on May 29, 1941, the 24th birthday of future President John Fitzgerald Kennedy. John Edward came to the major leagues with the Washington Senators during John Fitzgerald’s administration. A love letter to baseball’s Kennedy from his fiancée once was sent to the White House (where that type of mail may have been common during the early 1960s). A staff member at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue recognized the error and redirected the mail to the baseball Senators’ clubhouse. “There was nothing else, no note or anything, just a manila envelope from the White House,” the infielder said in an interview with the author on April 2, 2010.

John Edward Kennedy was born in Chicago on May 29, 1941, the 24th birthday of future President John Fitzgerald Kennedy. John Edward came to the major leagues with the Washington Senators during John Fitzgerald’s administration. A love letter to baseball’s Kennedy from his fiancée once was sent to the White House (where that type of mail may have been common during the early 1960s). A staff member at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue recognized the error and redirected the mail to the baseball Senators’ clubhouse. “There was nothing else, no note or anything, just a manila envelope from the White House,” the infielder said in an interview with the author on April 2, 2010.

Kennedy said his interest in baseball dated back at least to the day of Franklin Roosevelt’s funeral in April of 1945. “The funeral was on the radio and I was playing marbles on the floor with my dad. During the funeral my dad asked me, ‘Would you like to be President one day?’ and I said no, I want to be a baseball player. That’s in my baby book, and it’s the first record of my interest in baseball.”

Kennedy grew up as the shortstop and pitcher on his high school and youth teams. “I had a good arm, so they put me at shortstop and when we needed someone to pitch I went in there and threw fastballs,” He said. He was a good enough player that when he was about 15 he told a group of friends during an outing to Comiskey Park in Chicago, “I’m going to be out there one day.” Kennedy said the friends thought he was crazy, but six years later the dream came true. On September 7, 1962, in Kennedy’s first big-league start, he went 3-for-4 at Comiskey Park against Eddie Fisher and Don Zanni of the White Sox.

To complete the Comiskey Park connection, Kennedy’s father, Edward, drove a streetcar and then a bus for the Chicago Transit Authority and every day his route took him along 35th Street and right past Comiskey Park. Kennedy’s mother, Elsie, helped paste strips on globes for Rand McNally. Kennedy’s sister, Carol, retired as a dental assistant in 2009. As for the fiancée whose love letter was misrouted to the White House, she became Betty Kennedy later in 1962. Their two children, Scott and Kristen, presented them with four grandchildren.

Kennedy had a $5,000 offer from the Cleveland Indians when he signed with the expansion Senators in 1961 for $1,500. “I was all set to sign with the Indians and had been driven by Ted ‘Double Duty’ Radcliffe from Chicago to Cleveland for a workout. Ted had plenty of stories to fill time on the drive,” Kennedy remembered. “Before I signed, the Senators called me because one of my summer-ball coaches had become a bird dog for them and recommended me. Jack Sheehan was the supervisor, and he offered me $1,500, which I accepted. I felt that signing with an expansion team would be the quickest route to the big leagues, and it turned out to be a wise move.”

Kennedy played his first game in the big leagues on September 5, 1962, and in his first at-bat, pinch-hitting for Senators pitcher Ed Hobaugh in the sixth inning, he hit a home run that broke up a no-hit effort by pitcher Dick Stigman of the Minnesota Twins. Kennedy had been called up following a .302/.390/.419 season at Class B Raleigh of the Carolina League. He got into 14 games before the end of the season and batted .262. Back in the minors in 1963, Kennedy had a .290/347/.440 season split between Double-A York (Eastern League) and Triple-A Hawaii (Pacific Coast League). In 1964 he settled in as the Senators’ regular third baseman.

Unfortunately for Kennedy, his solid numbers in the minor leagues did not translate to major-league hitting success. He appeared in more than 100 games each season from 1964 to 1966 and had batting averages of .230, .171, and .201. And while he played in all or part of 12 seasons in the big leagues, accumulating an impressive 2,210 at-bats, it was as a utilityman. Except for a couple of stretches with the Los Angeles Dodgers, he never had another shot as a regular. “I don’t know why I didn’t hit,” Kennedy, a right-handed batter, said. “Preston Gomez (a coach for the Dodgers while Kennedy was with the team) said he couldn’t understand it because I had such quick hands. I think maybe my swing may have been too big. In Boston I switched to a bigger bat, choked up, and shortened my swing and hit a little better. By then, though, I was labeled as a guy who was good enough for somebody to want but not good enough to keep.”

On December 4, 1964, the 6-foot, 185-pound infielder was traded by the Senators with pitcher Claude Osteen and $100,000 to the Dodgers for outfielder-first baseman Frank Howard, infielder Ken McMullen, pitchers Pete Richert and Phil Ortega, and first baseman Dick Nen. “At first I was surprised because all the talk in Washington had been how they were going to build the team around Osteen, Ed Brinkman, and me,” Kennedy said. “But the number of players the Senators were able to get was staggering, so I understood.”

Kennedy said the Dodgers at first told him he would be the shortstop and that they would move Maury Wills to another position. Later that winter, though, Jim Gilliam retired and the Dodgers decided to install Kennedy as their regular third baseman for the 1965 season. Kennedy, however, did not hit and had developed some problems running. “I pulled my groin early in the season and I would ice it down before games and use the whirlpool after games and tried to play through it. Eventually, I overextended it running out a grounder and Gilliam came out of retirement and took over third base.” Gilliam’s first game back was on May 28, and Kennedy had four at-bats in a game only twice after that. His role on the eventual world champions became that of late-inning defensive replacement for Gilliam. Through May 28 Kennedy hit .213 with one home run, and he finished the season at .171 with no more homers. He had just 120 plate appearances in 104 games that season.

Despite losing his regular job to a coach who had come out of retirement, Kennedy said, he bore no ill will towards Gilliam. “I had a lot of respect for who he was and the career he had had with the Dodgers. Plus, he was a nice guy,” Kennedy said. “I knew when I would go into games, and I would get ready by going into the runway to throw and then stretch in the dugout. The only time I got upset was when (Walter) Alston left Gilliam in a game in St. Louis and he made an error that almost cost us a game. Then the next night we were ahead in a game, 5-0, and Alston pinch-hit for me. I came back in the dugout and threw my helmet and glasses down, and my finger got caught in the strap and the glasses landed near him. We then went into the runway together and had it out. We didn’t score many runs and played a lot of close games. I knew our best chance to win was to have me in there at the end. I played great defense that season.” Ultimately, Alston must have agreed with Kennedy, as he had him on the field at the end of Sandy Koufax’s perfect game on September 9 and at the end of the seventh game of the World Series that fall.

Kennedy’s role with the Dodgers in 1966 was expanded slightly. He appeared in 125 games and had 274 at-bats while hitting .201 with a .241 on-base percentage and a .281 slugging average. The Dodgers again won the pennant but lost the World Series to Baltimore. Gilliam again started the season as a coach, but was activated in April and took over third base. Kennedy played a bit more due to minor injuries to Wills and the reduced effectiveness of Gilliam, who retired permanently as a player at the end of that season.

During those World Series seasons, the Dodgers were led by their pitching staff, particularly Koufax and Don Drysdale. “If Walter Johnson and Cy Young were better than Sandy in his prime I’d have to see it,” Kennedy said. “Sandy was far and away the most dominating pitcher I ever saw. People don’t realize what he had to do to play those two seasons. Trainers would apply capsulin with a tongue-depresser. He’d come in after the first inning and complain about not being able to get loose after he’d blown them away, and we knew the game was in the bag. Then after the games he’d go straight from the heat of the capsulin to a tub of ice. How he did it, I don’t know.

“Everyone wanted Sandy to pitch Game Seven in 1965 (Koufax had two days’ rest, Drysdale three). That’s not a knock on Drysdale, but if the season was on the line for one game you wanted Sandy out there. Normally Sandy had great location with two pitches, but he beat the Twins that day with just his fastball. Drysdale was workmanlike, but Sandy was an artist. Both were exceptional.”

Kennedy appeared in both the 1965 and 1966 World Series. He was given the traditional ring for the Dodgers’ 1965 win over Minnesota. In 1966 the Dodgers awarded Rolex watches to players as mementos of their National League championship. Kennedy said he lost his ring in 1970 and was allowed to purchase a replacement for $650. He still has that ring but no longer wears it. He gave the watch to his son. Kennedy also received an American League championship ring from the 1975 Red Sox and a National League championship ring from the 1993 Phillies when he worked as a minor-league manager and a scout, respectively. “I still have those rings but they don’t mean anything to me because I didn’t play for the teams that won them,” he said in 2010.

On April 3, 1967, the Dodgers traded Kennedy to the New York Yankees for pitcher Jack Cullen, infielder-outfielder John Miller, and $25,000. Kennedy says the Yankees told him they acquired him to play shortstop. “The problem that year was that I couldn’t catch the ball. I played very poor defense with the Yankees, and they eventually moved Ruben Amaro and Dick Howser in to play shortstop.” Kennedy’s fielding percentage at shortstop in 1967 was just .915, as he made 12 errors in 36 games at the position (29 starts). He was only a little better at third base, with four errors in 24 starts. His hitting was also weak at .196/.265/.235. It was no great surprise that Kennedy found himself in Triple-A in 1968 for the first time since 1963.

Kennedy split the 1968 season between the Yankees affiliate in Syracuse and the Pirates’ Triple-A club in Columbus. For the most part, he was able to see the situation as an opportunity. “I knew expansion was coming, so I wanted to do the best I could,” he said. The fly in the ointment, according to Kennedy, was that he did not get along with Syracuse Chiefs manager Gary Blaylock. “I sat on the bench behind a younger, lesser player and I didn’t like it.” Kennedy wouldn’t name the player, but based on data on baseball-reference.com it was likely Joseph Mackey, who hit .170 in 432 at-bats for the Chiefs that season, played 120 games at shortstop, and made 28 errors at the position.

Kennedy was shipped to Columbus while remaining the property of the Yankees. There he played for Johnny Pesky, who liked Kennedy and who Kennedy believes recommended him to the Red Sox in 1970, ultimately extending his big-league career another three seasons. Kennedy also helped himself with a .268/.347/.384 line in the International League and was purchased by the fledgling Seattle Pilots on November 13, 1968.

In Seattle Kennedy met up with his 1967 Yankee teammate Jim Bouton, who, unbeknownst to Kennedy, was putting together his classic book Ball Four. Kennedy had an unwitting starring role in the book. On page 221 of the original version, the June 18 diary entry reads in part:

John Kennedy flew into a rage at Emmett Ashford over a called strike and was tossed out of the game. Still raging, he kicked in the water cooler in the dugout, picked it up and threw it onto the field. Afterward, we asked him what had gotten into him. He really isn’t that type. And he said, “Just as I got called out on strikes, my greenie kicked in.

“I was buddies with Bouton. I didn’t know he was writing a book. Most of us didn’t know. I get asked about the greenie story at father/son dinners sometimes, and I tell them what Bouton left out is that I said what I did about greenies in jest.” Kennedy also said that Bouton was a nice guy then and is a nice guy now, but that the reaction among the players when the book came out wasn’t warm.

“Most of them felt violated,” Kennedy said of the 1970 Milwaukee Brewers, many of whom, like Kennedy, had been members of the short-lived Pilots in 1969. “They couldn’t understand how he could write the things he did about us, about Mickey Mantle, and about other players. Now, though, looking back on it, it all seems pretty tame.”

Kennedy’s bigger problem in 1969 was the lack of playing time. While he was back in the big leagues for the entire season, he appeared in just 61 games. What bothered him further was that Ray Oyler was playing ahead of him at shortstop for the Pilots despite hitting just .165 after a .135 season in regular duty for the 1968 Tigers. In other words, Oyler’s anemic hitting was well established. Kennedy, though, said he believed that performance was a secondary consideration for manager Joe Schultz. “The Pilots had set up a fan club for Oyler and I believe they felt they had to have him on the field,” Kennedy said. “He was a popular player.” Kennedy hit .234 with four homers for the Pilots in his limited role.

Kennedy opened the 1970 season with Milwaukee after the Seattle Pilots franchise became the Milwaukee Brewers in spring training. Despite a solid .255 average with a couple of homers as a part-timer, Kennedy was dispatched to Triple-A for about a month before being purchased by the Red Sox on, Kennedy believes, Pesky’s recommendation.

From his arrival in Boston on June 26, 1970, until his release in October 1974, Kennedy enjoyed his longest continuous stretch with one club. He hit better, played more games, and played all over the infield (plus designated hitter) during his Red Sox years. The two World Series appearances with the Dodgers were special, but Kennedy said he made his reputation in baseball during his time with the Red Sox and was able to set himself up for a career in the game after he was done playing.

“I always ran as hard as I could and played as hard as I could throughout my career,” Kennedy said. “Shagging, throwing batting practice, and all that is part of the job and a way to increase my value and improve my chances of staying in the game. I threw batting practice to Yaz after games if coaches weren’t available. When I went down to Pawtucket during the 1974 season, I worked with [Jim] Rice and ]Fred] Lynn and threw them extra batting practice. I told [Pawtucket manager] Joe Morgan that I was going to retire at the end of the season and to let the young kids play and I would work with them to help them get better. I think I got a [minor league] managing job with the Red Sox in 1975 as a result.”

Kennedy said he regretted that the Red Sox played one less game because of the rules put in place after that year’s players’ strike, and lost to Detroit by a half-game. Everyone remembers the base-running mistake that helped end Boston’s hopes on Oct. 2, but Kennedy noted that almost the exact same thing happened on Opening Day. “We let Lolich off the hook in the first inning of the first game. Yaz thought Aparicio was going to score and kept going to third when Luis stayed put,” He said. The Red Sox got a run in that first inning but had four hits in the inning and left two on base. Boston had only two hits the rest of the way. “You can’t let a good pitcher or a good team off the hook like that, and we did it twice,” Kennedy said, noting how either of those losses, in two separate games nearly six months apart, would have wiped out that half-game deficit at season’s end.

Starting with Winston-Salem in the Class A Carolina League in 1975, Kennedy managed for three years in the Boston organization and one with Oakland before becoming a scout. “I encouraged my players to go all out all the time,” Kennedy said. “Not everyone is going to play in the big leagues, but if you give your best effort every day you can have peace of mind. If you don’t, you take the what-ifs to your grave.” Kennedy scouted until 2001, and then returned to the dugout from 2003 through 2006 with the North Shore Spirit in Lynn, Massachusetts, which played in the independent Northeast League and the Canadian-American Association during Kennedy’s tenure. “It was 20 minutes from my house and I was only gone a week at a time, so it was too convenient to pass up,” He said. Regarding his scouting career, Kennedy said, “I didn’t have any big signings. A couple of guys made it to Triple-A, but no one you would know.”

In his later years, John lived with Betty in Peabody, Massachusetts, where they were retired and spent a lot of days with their grandchildren. He died peacefully at home at the age of 77 on August 9, 2018.

Sources

The author interviewed Kennedy on April 2, 2010, and also relied on the web sites baseball-reference.com and retrosheet.org, and the 1966 Los Angeles Dodgers yearbook.

Full Name

John Edward Kennedy

Born

May 29, 1941 at Chicago, IL (USA)

Died

August 9, 2018 at Peabody, MA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.