Nellie King

“Hell, Wayne King was an orchestra leader!” Nellie King recalled years later.

It wasn’t unusual for Tex to get the first names of rookies wrong. According to Ben Wade, one of King’s teammates and a former Dodger pitcher, Ricard made this mistake often. It seems that the veteran announcer rarely knew the first names of rookie players. So he would trustingly seek help from the Dodger dugout. The Brooklyn players were always happy to oblige. They would supply him every name but the correct one. Tex would then announce it.

After completing his obligatory warm-up pitches, the rookie pitcher waited for the sign from Toby Atwell, his catcher. Stepping into the batter’s box was future Hall of Famer Duke Snider

Nellie was a right-handed sidearm pitcher who specialized in keeping the ball low; Snider, a left-handed power hitter, was a notorious low-ball hitter in a ballpark with a short right field porch. Atwell signaled for a sinker for the first pitch. King got it near the outside corner, causing Snider to foul it off for strike one. He followed this up with a curve that broke inside for a ball, then another curve that the Duke of Flatbush hit foul. Atwell went back to the sinker, and for some unknown reason, Duke fouled off an attempted drag bunt for strike three. Nelson Joseph King had struck out the first major league hitter that he faced

Nellie had finally made it after toiling in the minor leagues for eight years. The next morning, he scoured the New York streets in search of evidence. In the early edition of the New York Daily News, he saw see his name in the box score: “King. 1 inning, 1 hit, 0 walks, 1 strikeout.” Even if he never appeared in another game, the box score confirmed that he was a major leaguer

Nelson Joseph King was born on March 15, 1928, in Shenandoah, Pennsylvania, to Charles and Amelia King. He was the last of their five children. Young Nelson began his life growing up in the hard coal mining village of Weston Place. His father Charles died in 1933 at the depth of the Depression. With no Social Security or other relief or aid, it became impossible for his mother to keep the family together. Amelia enrolled her youngest child in the Milton Hershey School for orphan and part-orphan boys. Nellie admitted to a sense of abandonment, one that stayed with him for the rest of his life. The thing that never abandoned him was his love for baseball. He would dream of being a big league ballplayer.

Chocolate lovers across the nation know the name Hershey because of the famous chocolate bars, but Milton Hershey’s success in that business afforded him the opportunity to become a philanthropist. In 1909, after learning that he and his wife Kitty were unable to have children, Hershey decided to establish a school for orphan boys. Hershey signed over the 486-acre farm where he had been born to start the school. The first students arrived in 1910. When Nellie attended the institution, there were eighteen other boys. He credited his days at the school for instilling strong values and a healthy work ethic. If “idleness is the Devil’s workshop,” Nellie recalled, “with 30 head of Holstein cows to take care of, I quickly learned that I was never going to get near the devil’s workshop!”

One of King’s most cherished and vivid memories go back to 1941. While on a two-week vacation from school, the thirteen-year-old Nellie attended his first major league game. His older brother and his namesake Uncle Nelson took him to Shibe Park in Philadelphia to see the Phillies square off with the Cincinnati Reds. At the time, he did not pay much attention to the home team’s keystone combination of Bragan and Murtaugh. Coincidentally, he pitched for both while they were managers. Nellie pitched for Bragan at Hollywood in 1955 and in Pittsburgh the following year. Danny Murtaugh managed King in the minors and with the Pirates in 1957. Not coincidentally, Murtaugh would be his daughter Laurie’s godfather. That day, Nelson was more concerned with spotting Reds players Paul Derringer, Bucky Waters and Ernie Lombardi.

During the Forties, fans were able to exit from the playing field at Shibe Park. As the Kings walked past the visitors’ dugout, his brother remarked that both Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig had sat there. Fourteen years later, on April 24, 1955, Nellie would also sit there in a Pittsburgh Pirates uniform and make his first major league start that day against the Phillies.

Nellie King began his professional baseball voyage in 1946. The young man earned $100 per month to pitch for Albany Cardinals of the Georgia-Florida League. His first uniform was once worn by Enos Slaughter. That year he also experienced the disappointment that falls upon most young ballplayers, being cut loose from a team. Unfortunately, this occurred occur twice for King that year. The young pitcher was released first by the Albany Cardinals and then New Iberia of the Class D Evangeline League. Many other young men in the same situation might opt for a different direction, another profession, but Nellie knew that all he wanted to do was play baseball.

The following year, Roy Dissinger, a scout with the Cardinals and Red Sox who owned his own farm system, invited Nellie to spring training. The young pitcher remembered it as an odd experience. Roy told him that he wanted to see him pitch and not to worry about getting anyone out. Nellie remembers performing adequately but probably not well enough to make the team. He recalled leaving the field and walking up a hill and across a football field to get to the dressing room. He sat down on a bench by himself, immersed in unhappiness because of his poor performance and began to cry. “Then, I kind of said, it’s God’s will and I’ll accept it.” The young man walked back to where they were deciding who made it. To his surprise he was picked for the Geneva team, another Class D entry. He was to start his season as a member of the Geneva Red Birds of the Alabama State League.

In the first game that he started, King pitched a 2-1 game. Still, Nellie never felt quite welcome by manager Jim Francoline. While he was never afraid to throw strikes, he did not have any movement on his fastball. Then he received the best advice of his young career. It proved to be a defining moment. Cotton Bosarge, the second baseman on the club, noticed Nellie’s pitching. “You know, I watch you pitch and, damn, you have good control and keep the ball down low but your fastball doesn’t have any movement on it at all.” Cotton went on to ask how Nellie gripped the ball. Nellie replied that he held it across the seams like Bob Feller. This cracked the Southern boy up. “Christ, kid, you can’t throw as hard as Bob Feller!” He suggested that Nellie hold it with the seams. That little piece of advice changed his career. It caused his ball to sink. That year with Geneva, he posted an 8-11 record. The team finished in last place, 41 ½ games out of first place.

The following year, the Pittsburgh Pirates bought Dissinger’s whole minor league operation. King went to spring training in 1948 and impressed many of the scouts. One even compared him to Ewell Blackwell, who was a hero to Nellie. The scout went on to tell him how he missed out on signing Blackwell and did not want to miss signing King. Lenny Yochim, his former pitching mate and good friend, recalled that Nellie had his breakout year at New Iberia, Louisiana, of the Class D Evangeline League. He pitched on a schedule of every three to four days. That year he accumulated 284 innings and posted a record of 20-13. The team finished in sixth place. It was a tough league, made up of older players. George Stumpf was his manager.

The next spring Nellie attended camp with the New Orleans ball club. It was decided that he would start the 1949 season at York, Pennsylvania, of the Class B Interstate League. It was not a very successful team in a very good league, King recalled. Still, Nellie considered his experience there his first test against higher talent. That season he produced a commendable 16-15 record while leading the league with an ERA of 2.25.

In 1950, the young sidearm pitcher once again attended camp with the New Orleans club. As in the preceding year, he was sent elsewhere. This time it was Charleston, South Carolina, of the Sally League to play for Rip Sewell. He started occasionally but with little success. King described it as a funny atmosphere playing there. He’d go out for an occasional beer with teammates. Since Charleston was a Navy base city, sailors often came to the game and made a sport of “ragging” on the players. He enjoyed bantering with them. Nellie eventually became friends with some of the regulars. The season was Sewell’s first as a manager. King describes him as an intense man who hated to lose.

One example of Sewell’s competitiveness occurred at a home game against Greenville, a Dodger farm club. Sewell inserted himself as the starting pitcher. In the fourth inning, Omar Tollson stepped into the batter box. Rip decided to throw him his famous “eephus” pitch. Omar ripped it, hitting it harder and farther than had Ted Williams in the 1946 All-Star Game. This angered the veteran pitcher. It was the only other time that he surrendered a home run on the pitch. Nellie considered Sewell a good person but added that Rip never shared any pitching advice with him.

Just as King’s professional baseball career began picking up steam, Uncle Sam cooled it all down. He served in the army between 1951 and 1952 during the Korean conflict. Nellie was stationed at Fort Dix in New Jersey. He recalled that the roster of the army’s baseball team had some good talent. It included several professionals, but the better-known players were shipped to more obscure locations. Don Newcombe, for example, was there for a short period before being shipped to more obscure places. Since the camp was near New York City, officials were afraid that it might disrupt the camp’s operations. Nellie confessed that he did not enjoy life at the army base and found it difficult to find anything good about it. One positive thing that occurred was meeting his future wife on a blind date. Bernadette Earl’s brother was a teammate on the Fort Dix squad.

King returned to his preferred career with some flair in 1953. Nellie played with the Denver Bears of the Class A Western League. Nellie was being groomed as a closer. He only started two games, and his totals for the year were a 15-3 record with 17 saves. He maintained a 2.00 ERA and earned All-Star honors. The Bears’ manager was Andy Cohen, who had first gained notoriety as a college basketball player at Alabama, then for playing second base for the New York Giants as the player who replaced Rogers Hornsby. While King’s season in Denver was significant because of his conversion to relief pitching, it was also eventful because it marked the first time Nellie played with an African American or Latin American: Curt Roberts, the first to break the color barrier with the Pirates, played second base.

The Denver club played at Bear Stadium, which held 15,000-18,000 fans. Nelson Joseph King was a popular pitcher. He demonstrated exceptional control. Nellie had 22 walks for the season, and four of them were intentional. He remarked that the thin Colorado air did not effect his pitching: “I had a hard time throwing a home run ball while in Denver.” Because of his biting sinker, hitters generally pounded his pitches into the ground. Nellie started the season off with thirteen consecutive wins.

After the season, Nelson Joseph and Bernadette Earl were married on October 10, 1953, at St. Joseph’s Church in Newark, New Jersey. The morning after the wedding, the new groom picked up a copy of the New York Times and found out that the Pirates had purchased his contract. Turning to his bride he said, “If I had known this was going to happen, I’d have married you a couple of years ago.”

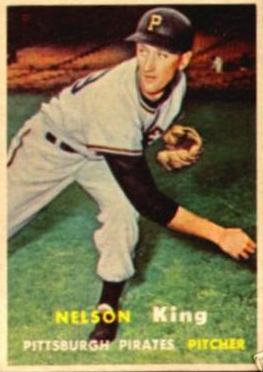

The rookie pitcher began the 1954 season with the parent club and stuck around for a month while producing no record. Before the 1954 season, Pirate General Manager Branch Rickey met with the Pittsburgh press at the William Penn Hotel on April 26 and remarked, “The tallest man in Pittsburgh, he’s 6 foot 8 or 6 inches, Nelson King. He is quite a comedian, but also has something above the neck. This boy is quite a character, but can also pitch.”

After his short time in Pittsburgh, King traveled south to New Orleans to play under the tutelage of Danny Murtaugh. Nellie won 16 and lost 5 while posting an ERA of 2.25, which led the Southern Association that year.

Nellie started the 1955 season in Pittsburgh and stayed for three months, winning one and losing three. This was to be the year that King thinks he established himself as a major league pitcher. Others agree, as does Frank Thomas, the team’s resident slugger: “Nellie King was an up and coming guy with a great deal of talent, too. He was a sidearmer, tall and lanky at 6 foot 6 inches and just 185 pounds, but he had posted some very impressive numbers in the minors. He’d been up with us very briefly in 1954, and although he appeared in only 17 games for us in 1955 he impressed everyone with his excellent sinker. He did a nice job for us out of the pen”

As far as Nellie was concerned, the turning point occurred when he pitched seven shutout innings in relief of Vernon Law against the Phillies to earn a save and followed it up by shutting out the Dodgers in relief three days later to earn his only victory of the year. Unfortunately, he battled not only National League hitters but injuries that season. A “dead arm” plagued him, causing the front office to farm him out. The young pitcher did not see much sense to this strategy. In fact, it cost him a chance to qualify for a major league pension.

King “rehabbed” with the Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League. Bobby Bragan was his manager and showed confidence in him. Nellie won a couple while losing three, and Bragan used him for the California State Championship. That winter the Pirates asked him to travel to Mazatlan, Mexico, to play winter ball. His stayed just a month, contracting dysentery, losing weight, and becoming too weak to pitch.

King considers 1956 the most enjoyable season of his brief major league career. Joe L. Brown, who was in his first season as a general manager, made a bold decision to go with a roster dominated with talented but inexperienced players. The team took its lumps but formed the nucleus of the 1960 team. Nellie was a part of this team that surprised everyone by moving into first place in the National League on June 20. He stayed in Pittsburgh for the entire year and had a record of 4-1, 7 saves, and an ERA of 3.15.

Also that year, against the Chicago Cubs, he threw a pitch that would signal the end of his major league career. The batter was Gene Baker. Catcher Jack Shepard called for a curve, and after delivering it, Nellie felt excruciating pain in his arm. Calling out to Shepard, he informed the catcher that he could not throw any more curves. He tried to rely on his fastball, but the same pain throbbed in his right arm.

King was never the same in 1957. He struggled all year with arm problems and posted a 2-1 record. That August 4, his first child Laurie was born. On October 7, 1957, three days before his fourth wedding anniversary, the arm injury forced him to retire from baseball at the age of twenty-nine.

Without baseball, the young father sought other means to support his young family. Former teammate Bob Friend helped him obtain a sales position selling Federated Investors Mutual Funds in Pittsburgh, which he tried in 1958. It was not enjoyable or productive, so Nellie packed up his wife and daughter and moved to Newark, New Jersey. Nellie took another sales position with John J. Ryan Municipal Bonds in 1959. He quickly realized that he had neither the desire nor the aptitude for selling, at least not bonds or mutual funds. As far as he was concerned, there were four years that he was not happy with what he was doing–two years in the Army and two in sales.

Yet Nellie was able to keep a positive attitude and strong faith that things happen for a reason. He had great admiration for Branch Rickey and enjoyed quoting the Mahatma’s analogies. One of Nellie’s favorites concerned finding happiness. “Mr. Rickey likened happiness to a ‘cur-dog.’ There was a worker who was busy painting a garage. Just as he was beginning to paint he noticed a cur dog nearby. Fascinated by the dog, he reached down and tried to pet the animal. As soon as he did, the dog ran away. So the painter returned to his job and soon the dog returned. The dog rubbed up against his leg; unaware of the dog, the man kept painting and whistling. Suddenly he felt the dog reaching up and pawing at his thigh. Mr. Rickey would go on to explain, ‘That’s what happiness is. You can’t go out looking and searching for it, if you do, it will escape from you and run away like that cur-dog. But if you go about your work, enjoying it, happiness will be there right beside you.’”

Nellie ultimately found his true second career, broadcasting. He owed thanks to Jack Berger, the Pirate Public Relations Director. Joel Rosenblum, who owned several small radio stations in Western Pennsylvania, called Jack to inquire if he could recommend a former player to do sports for his stations. Rosenblum, who was naïve concerning the sports world, originally wanted to get Joe DiMaggio. Realizing how absurd that idea was, Jack recommended Nellie. So, in 1960 Nellie began doing sports at small radio stations in Kittanning, Latrobe and Greensburg, Pennsylvania. Nellie also hosted a daily sports show, including one of the first sports talk shows in the Pittsburgh area in 1962. He covered the Masters, US Open and PGA Championships from 1961 to 1966. The latter included eight daily radio reports on the play of Latrobe’s very own Arnold Palmer.

In 1967, the position of color commentator on the Pirates’ broadcast opened when Don Hoak decided to return to baseball as a coach for the Phillies. King did not apply for the position but learned that he was considered the prime candidate after reading Al Abrams’s column in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Nellie figured, “I might as well apply, what do I have to lose? I already have a good job at WHJB in Greensburg.” Nellie was chosen for the job and began a nine-year association with the legendary Bob Prince.

The broadcast team consisted of Bob Prince (The Gunner) and Jim Woods (Possum). “They were both great on the air and the life of the party off the air,” Nellie remembered. For his first year or so, King assumed an obsequious role. “I really did not like myself.” The former Pirate broadcaster did not hide the fact of his relationship with Bob Prince did not start off well. It seems that Prince was not thrilled with having “jocks” joining him in the booth. The Gunner showed King up on the air a couple of times. It seemed that Bob treated Nellie as his assistant. Eventually Nellie became fed up with being belittled and threatened to “punch him out” if Prince pulled that type of stunt again. “That seemed to clear the air. After that we got along fine. We were good friends. We had arguments and happy times, like anybody else.”

Nellie King’s strength was an ability to tell a story at the drop of a dollar bill or a familiar name. “Rege Cordic once told me that the secret of radio is getting past the microphone or the speaker. He said you’ve got to get through that radio and into the home of the listener. You’re out there with the guy or gal, sitting right next to them and talking just to them.”

According to Nellie, Bob Prince made more money from various sidelines and enterprises than from his base compensation. The Pirates never paid Prince more than $40,000 a year for broadcasting. This fact might have had an adverse effect on Nellie’s salary negotiations over the years. The Pirates did not feel justified to paying him more money than the “voice of the Pirates.” According to Dave Giusti, the former Pirate pitcher, Prince had inherited a considerable sum from his parents and didn’t really need the money that he earned for broadcasting Pirate games.

Together, the team of Prince and King would broadcast an exciting era of Pirate baseball. Prince referred to it as the “Halcyon Days” of Pirate baseball. Current Pirate color analyst Steve Blass thinks that Nellie had a great style of interviewing. Blass thought that King’s best quality was to make the person he interviewed comfortable. He credited King’s pleasant style. Steve believed they might have made a great team in the booth.

The apex of the team of Prince and King was the World Series Championship of 1971, but four years later the tensions between KDKA, the sponsors and Prince proved irreconcilable and led up to their firing. Nellie remembers the day it happened–October 27, 1975. He noted, “I had no idea they were dissatisfied with me. I knew that Prince had his troubles with KDKA. I didn’t know I was in trouble until Joe Brown called me and said that he wanted to meet with me before he went on a three-week vacation. At the time, I thought he wanted to speak to me about the speakers’ bureau that I had been heading up for the ball club.” Before King went over to meet with Brown, he decided to check his contract, because he had a feeling that it was due to expire. Nellie saw that it ended on November 1. Before he left the house, his daughter Leslie asked him where he was going and he told her. Not realizing how prophetic she was, Leslie joked, “He’s probably going to fire you.”

When he arrived at Brown’s house, Joe asked him if he wanted a drink. Like any good Pittsburgher, he asked for an Iron City beer. Brown did not have one. Nellie smelled trouble. “Then he said, ‘I have some bad news for you. You’re not coming back as an announcer next year.’ I couldn’t believe it. I was really shaken.” The Pirate GM told him that Prince was having troubles with KDKA and that he was probably also about to go. Then he said, “Sometimes water splashes over onto other people.” King replied, “That is a helluva reason to lose a job.” Brown told Nellie that KDKA did not believe that he was capable of becoming the number one broadcaster in the booth; they wanted someone younger, who could develop into the number one guy. Brown also revealed that a roundtable of the Pirates, KDKA and the brewery considered King’s performance fair at best. To rub salt into the wound, Brown offered Nellie a job in the PR department, at $18,000 a year. As the #2 man in the booth, he was pulling down $28,000. He replied to the Pirate GM, “I am disappointed in you. I’m not sure that I want to work for the Pirates anymore.” While Nellie’s reaction was anger, the news crushed Prince.

One of KDKA’s rival radio stations hastily organized a parade to honor the fired broadcasters. It had been noted that prior to the event, it was Election Day with the lowest turnout in thirty-five years for the city. Yet, an estimated of 10,000 lined the streets of downtown Pittsburgh to take part in the demonstration. Several fans carried signs, one imaginative one read “Bring back royalty to Pittsburgh–Prince and King.”

Unfortunately, the powers-that-be stuck to their decision: Milo Hamilton and Lanny Frattare were hired as their replacements. Nellie’s philosophy has always been that “ when a door closes in your life, another one opens. The one that opened has always turned out to be better than the one closed. It doesn’t seem like it at the time but it does.”

King had once recommended Huddie Kaufman, long-time sports writer for the Greensburg Tribune-Review, for the sports information director’s job at Duquesne University. Instead, it was offered to Nellie. He stayed in this position for seventeen years, from 1976 to 1993. His wife earned her Master’s Degree in education, and all three of their daughters (Laurie, Leslie and Amy) graduated from Duquesne.

Nellie also broadcast basketball games for the school on WDUQ-FM with Ray Goss for 24 seasons. He served as the coach of the university’s golf team until 2004. Under his coaching his team won the 17-team Lafayette Invitational during 2001-02 and placed a school-best third at the 2000 Atlantic 10 Championship.

Nelson Joseph King has been honored with the Art Pallan Award (named for a KDKA deejay) for his service to the community. He has been involved with Mercy Hospital’s Heart Programs and the Boys and Girls Club of Western Pennsylvania, and worked with Sally O’Leary of the Pirates’ Alumni Association. King is also a member of the Western Pennsylvania Chapter of the Pennsylvania Hall of Fame.

Nellie has written his memoirs entitled “Happiness is like a Cur Dog: The thirty year journey of a major league baseball pitcher and broadcaster.” His story is that of a young boy born in the Pennsylvania coal mining region, attended the Milton Hershey School for Orphans, only to live out his dream of being a major league baseball player. When that dream abruptly ended, he went go on the air to share his love for the game.

As far as Nelson Joseph King is concerned, he starred in his own version of “It’s a Wonderful Life.”

After several years of health issues, including colon cancer and pneumonia, Nellie King died at 82 years old on August 11, 2010.

Sources

The Baseball Index

SABR’s on-line Encyclopedia

Finoli, David, and Bill Rainier, The Pittsburgh Pirates Encyclopedia, N.p.: Sports Publishing L.L.C., 2003.

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff, eds. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America Inc., 1997.

O’Toole, Andrew, Branch Rickey in Pittsburgh: Baseball’s Trailblazing General Manager for the Pirates, 1950-55, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2000.

Thomas, Frank, Ronnie Joyner, and Bill Bozman, “Kiss it Goodbye!” The Frank Thomas Story, Pepper pot Productions, Dunkirk, Maryland.

O’Brien, Jim, We Had ‘Em All the Way, Pittsburgh: James P. O’Brien Publishing, 1998.

“The Black and Gold,” Official Newsletter of the Pittsburgh Pirates Alumni Association. Vol. 19 NO.1, June 6, 2006, Vol. 20, No. 1 January 2007, Vol. 20, No. 2, July 2007 (Courtesy of Sally O’Leary)

King, Nelson Joseph, “Nelson ‘Nellie’ King Biography and Introduction,” from unpublished manuscript (Courtesy of Amy King)

King, Nellie, “Pittsburgh Pirate Baseball Memories,” from the Peacock Chronicle website, 2002.

King, Nellie, “Facing Down Dodger Blue,” Elysian Fields Quarterly, 2006.

Telephone Interviews

Nellie King, July 23, 2006 & September 23, 2007

Sally O’Leary, September 9, 2007

Lenny Yochim, September 9,2007

Dave Giusti, September 10, 2007

Steve Blass, October 14, 2007

Photo Credit

The Topps Company

Full Name

Nelson Joseph King

Born

March 15, 1928 at Shenandoah, PA (USA)

Died

August 11, 2010 at Mount Lebanon, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.