Bumpus Jones

Charles Leander ” Bumpus” Jones began his major league career on Saturday, October 15, 1892, when he twirled a no-hitter for Cincinnati against the visiting Pittsburgs. Seemingly emerging from nowhere, Jones caused quite a stir in baseball circles. He was never able to duplicate his success in the majors. Whether it was the change in pitching distance from fifty to sixty feet in 1893 or a legendary beaning in the spring, Jones tenure in the majors was short-lived. His final appearance would be July 14, 1893, when he made his New York debut with a ten-walk performance in a loss to Cleveland and Cy Young.

Charles Leander ” Bumpus” Jones began his major league career on Saturday, October 15, 1892, when he twirled a no-hitter for Cincinnati against the visiting Pittsburgs. Seemingly emerging from nowhere, Jones caused quite a stir in baseball circles. He was never able to duplicate his success in the majors. Whether it was the change in pitching distance from fifty to sixty feet in 1893 or a legendary beaning in the spring, Jones tenure in the majors was short-lived. His final appearance would be July 14, 1893, when he made his New York debut with a ten-walk performance in a loss to Cleveland and Cy Young.

The Jones family originated in Virginia and resettled in Ohio in the 1800s. The 1840 census shows them living in Xenia Township in Greene County. Bumpus’ mother, Roseanna, was born there in 1851. She gave birth to Bumpus in 1870, apparently out of wedlock, because there is no mention of a marriage or a father. The official date of birth is January 1, but there is much speculation as to the authenticity of this date. In fact, Bumpus appears in the 1880 census as a nine-year-old, suggesting that at the time of the count he had not yet turned ten. There has been considerable speculation about Jones’ ethnicity. He is listed as mulatto in early census records and is listed as white on his death certificate. Genealogical research by a relative suggests that he was descended from Pocahontas’ people in Virginia. His mother, Roseanna, married James Jeffries on April 22, 1874. The Jeffries are frequently listed as black or colored in census records and obituaries and this has undoubtedly given rise to speculation. The marriage of Roseanna and James produced three more children, George, Charles and Nettie.

The Jeffries family moved to Cedarville, Ohio, where Bumpus was raised. Legends abound about Bumpus’ throwing ability as a child. He attended some school, worked in the lime kiln, and played baseball. Some of the earliest newspaper reports of Jones indicate that he had an “arm for hire.” In 1889, he made several trips to Cincinnati by rail to play for semi-pro teams like the Bond Hill Maroons and Linwood. Legend has it that he would be paid $6-8 per game. The Xenia Gazette covered a game between Xenia and Cedarville in September when Jones tossed a no-hitter for Cedarville. A follow-up article the next day made mention that Xenia was upset with their share of the gate. Cedarville had paid Jones and catcher Cal Morton $12 before splitting the remaining receipts.

Morton was the son of a Cedarville pastor and in 1890 was sent to college in Monmouth, Illinois. Legend has it that Jones also attended school there. Records show Morton as a student, but not Jones. Bumpus did, however, join the Monmouth team in the Illinois-Iowa league. He made his pro debut on May 13, 1890 and recorded an 18-1 victory over Joliet. He joined the rotation and took his regular turn in the box until he suffered an 18-2 loss to Dubuque on May30. Despite a 4-2 record, Jones was released.

On June 16, Bumpus debuted in the lineup for Aurora and exacted a measure of revenge by besting Monmouth, 6-2. He stayed with Aurora the remainder of the season. Aurora was in the race for much of the year and Jones compiled a record of 12 wins and 10 losses with them.

In 1891, Jones returned to the Illinois-Iowa league, but he opened the season with Ottumwa, which rankled the Aurora owners who claimed title to him. Bumpus pitched and played outfield for Ottumwa and had three wins before Aurora’s complaint was heard, at which time Bumpus was suspended pending league action. In late May, Jones was ordered to join Aurora. This Aurora team was a far cry from the 1890 version and had a record of 3-18 when Jones arrived. He lost his first start to Joliet, but victories in his next three appearances gave the fans some hope. The manager of the team quit in a dispute and the team went into a slide. The end came when Jones tossed a 6-hitter at league leading Quincy, but lost when his teammates made 11 errors and allowed 9 unearned runs. The team was disbanded the next day. Within hours Jones had signed on with Quincy and in his first appearance for them struck out 14 Joliet batters in a victory. Controversy again arose when Ottumwa claimed the rights to Jones. Once again the league President had to step in and negate Quincy’s claim and send Bumpus to Iowa. Jones piled up a 5-1 record before joining Ottumwa. Jones won four games in a brief stay with the team. In early August he was sold to Portland for $200. Portland was in the midst of the race with Spokane for the league title. Jones pitched relatively well, but compiled only a 5-6 record. Portland clinched the pennant, but when it came time for a series with the California league champion they released Jones and picked up pitchers from other Northwest teams. For the year Jones recorded 20 victories.

Jones joined the Joliet squad in the Illinois-Iowa league the next season. The Joliet ownership had assembled quite a powerful team that got off to an incredible start. By the end of June, Bumpus was 15-0 with six shutouts. The league was on shaky ground, teams began to fold, the second half schedule was redrawn, and Joliet played only .500 ball after the Fourth of July. When Joliet folded in early August, Bumpus was 24-3.

There was much speculation that he was trying to work a deal with Chicago, but this never materialized. Instead he signed on with Atlanta of the Southern Association. He also took a cash advance from Montgomery of the same league. Once again he found himself suspended. Eventually Jones would return the money to Montgomery and after two weeks in limbo would report to Atlanta. He debuted versus Macon on September 1, but lost on a ninth inning home run. Atlanta disbanded on September 20, with Jones having recorded a 3-4 record. The Atlanta Constitution reports that he returned to Cedarville.

In October, the Wilmington, Ohio, newspapers were filled with news that the Cincinnati Red Stockings were coming to town to play the Clintons in an exhibition. The local team picked up Bumpus for the October 12 game. He played some outfield and in the seventh came in to pitch. The Reds had already scored nine runs, but Jones shut them down without a hit. The Wilmington Democrat stated that Jones was invited by Charles Comiskey to come to Cincinnati and pitch on Saturday. October 15 was the final day of the regular season and would be the last time the pitcher’s box was at fifty feet. Bumpus faced a veteran Pirates team that featured Jake Beckley, Lou Bierbauer, Patsy Donovan, and Connie Mack. A nervous Jones walked the first two batters, then coaxed a grounder that was turned into a double play. In the second Jones again walked a batter, but he was eliminated by another double play. The Reds took the lead in the bottom of the second on a RBI double by Comiskey. In the third Donovan walked and stole second. He scored a run when Jones threw a bunt attempt into right field. The Commercial Gazette‘s report states ” that ended the run-getting of the visitors and not one of the Pittsburgs reached first base in the six closing innings.” The Reds scored 2 in the fifth on a Germany Smith homer and plated 4 more in the eighth for a 7-1 victory.

Bumpus became an instant sensation. Comiskey quickly signed him and Jones embarked on the post season tour. A shrewd businessman, Comiskey, started Jones when the Reds stopped in Springfield, Ohio ( about 10 miles from Cedarville). Bumpus was touched for seven hits, but still tossed a 12-0 shutout. Estimates set the crowd at between 1000-2000 fans.

The 1893 season opened with the pitching distance moved back to 60’6″. Cincinnati decided to train in the Queen City and have other teams visit for exhibitions and also play nearby amateur and semi-pro teams. Jones first action was in relief against a squad from Madisonville. He got his first start on April 13 when St. Louis was in town. He pitched very well and recorded a 12-3 win. On the 23rd he again faced St. Louis in the last exhibition of the spring. Bumpus went nine innings before being relieved. Jones first start of the season came on April 27 against Chicago. He was never able to get his arm loosened up and was quickly relieved. He lost his next start and then could only get to the second inning in his third outing. He was sent back home to “get the kinks out of his arm” according to the Commercial Gazette. When he returned Jones still was unable to regain the 1892 form. He became the forgotten man on the staff, seeing no action for three weeks. Finally on June 18 he was summoned to give Elton Chamberlain a rest when the Reds took a 14-0 third inning lead on Louisville. Bumpus would gain his only other major league victory with this appearance, but his performance was lackluster at best. He walked 6 and gave up 12 runs in a 30-12 win.

In mid-July, the New York Giants made numerous roster moves including signing Jones. He was quickly put to work facing Cleveland and Cy Young on July 14. The results were dreadful again. Bumpus walked 10, hit a batter, made an error and was lucky to only give up 6 runs. The Times reported that with some timely hitting Cleveland could easily have scored three times as many runs. This would be Bumpus’ last major league appearance. He stayed with the Giants for a few more weeks, but saw no action. In early August he was dealt to the Providence Grays. He made three mound appearances for the Grays and had a 1-2 record. He also had an appearance in right field. The September 2 Providence paper reports that Jones jumped the team to join Reading, but never appears in a box score for that squad.

Ban Johnson had been a newspaper reporter in Cincinnati in 1892. By 1894 he was President of the Western League and no doubt considered Jones a drawing card. Bumpus would find employment in the Western League for the remainder of the decade. In 1894 he was the third man on the staff of Sioux City. The Cornhuskers got off to a terrific start (31-9) on their way to the pennant. Jones compiled a 13-14 record with them, but he was traded in early September to Grand Rapids. With this new team he had a 3-3 record. The highlight for Jones came on Sept. 23 when he beat Sioux City 23-2 and hit a three-run homer to deep center field.

Grand Rapids changed their name to the “Gold Bugs” for the 1895 season. Bumpus was the pitching bright spot for this team, compiling an 11-20 record for a team that won only 38 games. He also became a fan favorite not only for his pitching, but for his antics on the field. The Indianapolis paper reports that in one game he went into a “delirium” at the plate and shook and wobbled to unhinge the opposing pitcher. The ploy worked as Jones was walked.

After a fairly nomadic career, Jones found a home with the Columbus team. Jones had married Effie Merritt and his only son would be born in 1896. Tragedy struck in mid-June when the team was on a road trip to Grand Rapids. Jones’ son died from unknown causes. Despite the sad news, Bumpus pitched and won, 8-2, and had 2 hits. For the season, Jones had a 13-17 record, but his pitching improved as the year progressed. Bumpus had a reputation for being a “warm-weather” pitcher. He struggled in early May of 1897 and was even left behind in Columbus when the team went on a western trip. The rest seems to have been the cure for Jones. He compiled a 17-6 record with an ERA of 1.45. The Ohio State Journal claimed he “had more speed than Rusie and a bigger curve than Breitenstein.” The next season Jones was the ace of the pitching staff and also took over the role of team comedian from the retired Arlie Latham. According to newspaper accounts, Bumpus would entertain the fans before the game with jokes and stories about Cedarville and its inhabitants. He won opening day with a 4-hitter versus Connie Mack’s Milwaukee team. On June 5 he tossed a no-hitter versus Kansas City, and in August he threw a one-hitter at St. Josephs. He ended the year with a 27-13 record, but showed serious signs of overwork by season’s end.

In 1899 Jones was joined by Rube Waddell. The two formed a formidable pitching duo, but Jones was wearing down and his performances became more and more uneven. Fan support was also dwindling in Columbus, and despite a winning record the franchise was moved to Grand Rapids in early July. A month later the papers reported that Jones had health problems, possibly malaria. When he returned to action he tried to assume a full workload, leading to outings like the one against Milwaukee when a Grand Rapids writer remarked, “The Foam Blowers found Bumpus’ curves as soft as a bunch of ripe bananas and he was reduced to pulp in two rounds.” Jones ended the year with a 15-16 record.

The Western League, under the presidency of Ban Johnson, in 1899 consisted of franchises in Buffalo, Columbus/Grand Rapids, Detroit, Indianapolis, Kansas City, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, and St. Paul. St. Paul, owned by Charles Comiskey, moved to Chicago and became the White Sox. For its part, Grand Rapids relocated in Cleveland, reincarnated as the Lake Shores. Johnson renamed the new group the American League. In 1901, he declared the American League a major league, fomenting direct competition for players with the National League and touching off a baseball war that would last through the 1902 season.

Bumpus was in the middle of it all, as the first player to report to the Cleveland Lake Shores in 1900. The Lake Shores trained in horrible weather in Cleveland, making it difficult for Jones to work into shape. Despite this he was selected as the opening day pitcher for the game in Indianapolis. His performance was not overpowering, but he did emerge victorious, 7-6. The unseasonable weather continued, the May 5 game was snowed out, and Jones struggled. Finally on May 11 he was released to Fort Wayne after a 1-2 record. The change of scenery helped Jones. He was 5-2 before being felled by illness in mid-June. He missed about two weeks and then slowly worked his way back to starting role. He had 5 straight complete game victories but was suddenly released in early August with some teammates. The Fort Wayne Sentinel reported that the players’ behavior had not been “suitable” and hinted that they were enjoying the nightlife at home and on the road. Wheeling quickly picked up Bumpus, who compiled a 3-3 record with them.

The 1901 season found Jones in the employ of the St. Paul Apostles. He was slated to be the number two man in the rotation behind Wee Willie McGill. This must have been one of the shorter pitching staffs in history. Both men are sometimes listed as 5’10”, but Jones is also compared to players like Davy Force who was only 5’4″. Jones and McGill were more likely 5’7″ or 5’8″. Bumpus’ only start of the season came on May 4 and he lost to St. Joseph. He was felled by an illness, and papers reported on May 27 that he was hospitalized with appendicitis. Newspapers around the Midwest noted his plight and there were collections and benefits held for him at various ballparks. There is no evidence that he pitched professionally again.

Once out of the hospital he found work with the National Cash Register (NCR) Company in Dayton, Ohio. In 1902 he played in the company league and occasionally flashed the form that made him famous. Newspapers reported in both 1903 and 1904 that he had signed with professional teams. In 1903 he was supposedly headed to Nashville but backed out because of illness. He was reportedly headed to Columbia, South Carolina in 1904 but never arrived.

Because of his no-hit feat it seemed any pitcher named Jones was dubbed “Bumpus” in the press and by fans. In 1904 alone there was a Bumpus playing in the middle of Kansas, another in the Detroit Industrial League and a third with Oakland on the West Coast. None of them were Charles Leander Jones.

Bumpus was still living in Dayton in 1905 according to the City Directory. He dropped from sight until a news article appeared in the Dayton Daily News on September 23, 1912. It reported he was a patient in St. Elizabeth hospital in Dayton and had recently been baptized in the Catholic Church. The implication was that he was in declining health and needed prayers and support. A benefit game was organized that would feature pro players from Dayton versus a similar contingent from Springfield, Ohio which was about 20 miles away. The game took place on November 3 in Dayton but was not the success organizers hoped for. For unknown reasons the Springfield squad did not arrive, and the Dayton team played a local semi pro team. The locals beat the pros 7-2 before a crowd of 500. No report was found concerning the funds raised in the benefit.

In 1920 it was reported in the Cincinnati Enquirer that his health was again an issue and that he was housed in the Montgomery County infirmary in Dayton. The report stated he was nearly blind. Both the 1912 story and 1920 story repeat the tale that he was beaned in a pre-season game (possibly in 1893 though the date is uncertain) and that was the source of his infirmities.

After his recovery and release he moved to Cedarville. He spent time in the local barbershop and whenever possible encouraged the children in their ball playing. One time, Cedarville kids took on a neighboring town in a game and Bumpus awarded one of his bats to the leading Cedarville hitter, Curtis Hughes. In the late 1980’s Hughes spurred a fund raiser and a suitable headstone, proclaiming Jones a “no-hit pitcher,” was placed on his grave.

His wife Effie passed away in September 1935. Bumpus suffered a stroke a few years later and died from complications on June 25, 1938. He was buried in Cedarville’s North Cemetery. His gravesite sits a short distance from Cedarville University’s ball diamond.

Sources

Genealogical research by Christopher Moore, located in the Greene Room of the Greene County Library in Xenia, Ohio.

Interview with Curtis Hughes and other Cedarville old-timers.

Koppett, Leonard. Koppett’s Concise History of Major League Baseball. Updated and Expanded Edition. New York: Carroll & Graf, 2004.

McDaniel, Rachael. “Bumpus Quest.” Baseball Prospectus, January 28, 2019. https://www.baseballprospectus.com/news/article/46758/defensive-indifference-bumpus-quest-part-1/

Newspapers from Chicago, Aurora, Ottumwa, Quincy, Portland, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Joliet, Atlanta, Cincinnati, Wilmington (Ohio), Providence, Reading, Sioux City, Grand Rapids, Indianapolis, Columbus, Cleveland, Fort Wayne, Wheeling, St. Paul, Cedarville, Dayton, Springfield, and Xenia.

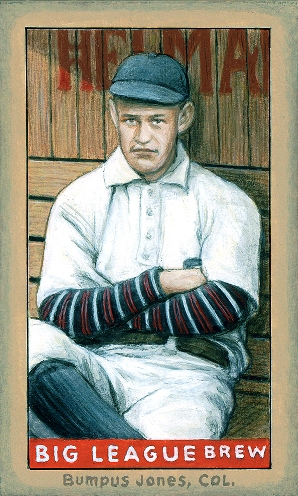

Photo Credit

Monty Sheldon

Full Name

Charles Leander Jones

Born

January 1, 1870 at Cedarville, OH (USA)

Died

June 25, 1938 at Xenia, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.