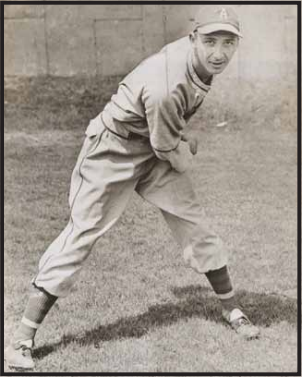

Len Gilmore

One of the things the classic movie Field of Dreams brought to light, via the tale of the now-legendary Archibald “Moonlight” Graham, was plight of the many players who had a chance to play in only one major-league game. During the war years, the Pittsburgh Pirates had a 6-foot-3, 175-pound pitcher by the name of Leonard Preston Gilmore, who, while garnering a few more statistics than Graham, still was of Moonlightian quality; his entire major-league career consisted of a single contest.

One of the things the classic movie Field of Dreams brought to light, via the tale of the now-legendary Archibald “Moonlight” Graham, was plight of the many players who had a chance to play in only one major-league game. During the war years, the Pittsburgh Pirates had a 6-foot-3, 175-pound pitcher by the name of Leonard Preston Gilmore, who, while garnering a few more statistics than Graham, still was of Moonlightian quality; his entire major-league career consisted of a single contest.

Len Gilmore was born on November 3, 1913, in Fairview Park, Indiana. His father, Sydney, was a US native who was a laborer in the mines; his mother, Margaret, was a native of Austria. Gilmore attended Indiana State Teachers College (now known as Indiana University of Pennsylvania), a state college about 60 miles east of Pittsburgh from 1936 to 1940. Four years after leaving the school, the lanky right-hander became the fourth of five players from the college to play major-league baseball, joining Hutch Campbell, Mike Menosky, Cy Rheam, and Billy Hunter.

While still at Indiana State Teachers College, Gilmore began his minor-league career in 1938 with the non-affiliated Refugio Oilers of the Class D Texas Valley League, where he had a 5-4 mark with a less-than-stellar 5.46 earned-run average. Despite the unimpressive debut campaign, Gilmore moved up to the Bisbee Bees in the Class C Arizona-Texas League in 1940. During the season the Cincinnati Reds acquired his contract and sent him to the Tucson Cowboys, their affiliate in the same league.

Gilmore won nine games and lost five, but struggled with both clubs, finishing with an ERA over 5.00 again. The Reds dropped him and he played independent ball in Arizona in 1942 while expecting to be drafted into the armed forces. But eventually he was classified 4-F, physically unfit for service, and the Pittsburgh Pirates farm director, Bob Rice, brought him to the team’s Muncie, Indiana, spring-training camp for a tryout in 1943. Though he had been out of Organized Baseball for two years, Gilmore made an impressive showing, and was assigned to the Pirates’ Albany farm team in the Class A Eastern League.

In his first season with the Senators in 1943, the 25-year-old Gilmore established himself as a legitimate prospect, going 13-5 with a six-game winning streak, and reducing his ERA to 2.90. As impressive as that was, it was just a precursor to what proved to be the best campaign of Gilmore’s career, as he dominated the Eastern League in 1944 with a 21-5 record.

Never much of a power pitcher, relying on control (only 2.4 walks per nine innings in his 11-year minor-league career), Gilmore was perhaps the most effective hurler in the league. After defeating Hartford for his 18th victory, and the Senators’ 12th in a row, and beating the Utica Blue Sox, 15-5, to secure his 19th, Gilmore became the league’s first 20-game winner of 1944 by defeating Williamsport, 3-1. Gilmore considered the victory the highlight of his career; he recalled the game vividly in a newspaper interview the next year. “We were ahead 3-1 in the ninth, two men were out,” he said. “I remember, even under such favorable circumstances, that I had twice failed to register number 20. The opposing batter was outfielder Wally Michie. He’s a lefty who feeds on us right-handers. I got him two strikes and nothing. Then I poured over a fast one, on the inside corner. The batter took it and the game was over. My catcher, Tony Rensa, stuck the ball in his pocket but not for long. Tony said, ‘You know who should have that ball.’ He knew and I still have it.”1

Gilmore won one more game to give him a 21-5 mark with a 2.63 ERA, and earned a spot on the postseason Eastern League all-star squad as the circuit’s top pitcher. His statistics impressed not only the fans of the Albany Senators, but also Pittsburgh farm director Rice, and after the Eastern League season ended, Gilmore was called up to the Pirates along with infielder Vic Barnhart, first baseman Harry Sweeney, and outfielders Al Gionfriddo and Bill Rodgers. Gilmore was thrilled to be on the major-league club, but sat on the bench until the last day of the season, when he was scheduled to start for the Pirates.

While it had been early June since the Pirates had been in serious contention for the National League pennant (the St. Louis Cardinals finished in first place with 105 victories), Pittsburgh nonetheless had a solid campaign, with 90 victories, and had held onto second place since August 10. Led by first baseman Babe Dahlgren, who knocked in 101 runs while hitting .289, and 37-year-old hurler Rip Sewell, who won 21 games, the Bucs came into the last day of the season with a doubleheader scheduled in Philadelphia against the last-place Philadelphia Phillies, or Blue Jays as they called themselves in 1944 and 1945.

In the first game Sewell scattered nine hits and left fielder Jim Russell was 4-for-6 in an easy 9-1 win. In the nightcap, Gilmore would not have the benefit of the potent Pirates attack supporting him, as manager Frankie Frisch also chose to give starts to little-used youngsters like Gionfriddo, Rodgers, and Barnhart; Dahlgren was the only regular to start and he was lifted after one at-bat.

Gilmore was solid if unspectacular in his first seven innings of work. Catcher Bob Finley singled home Ron Northey (4-for-4) to give Philadelphia a 1-0 lead in the second, and the Blue Jays extended the lead to two runs on a fly ball by Coaker Triplett in the fourth. Pittsburgh cut the lead to one in the fifth when catcher Spud Davis sent a Dick Barrett offering into the left-field upper deck at Shibe Park. That was the extent of the Pirates offense; Barrett limited them to three hits. Northey hit a home run in the sixth, but Gilmore looked impressive through seven innings, and Pittsburgh went into the eighth down only 3-1.

The eighth inning proved to be Gilmore’s undoing. Northey smacked his second homer of the game, a two-run shot, and hits by Glen Stewart and Granny Hamner drove in two more runs to give Philadelphia a decisive 7-1 victory.

While it wasn’t a horrendous performance, and he didn’t walk a batter, Gilmore nonetheless gave up 13 hits in his complete-game performance. The Pittsburgh-Post-Gazette was generous in its description of his debut: “Leonard Gilmore made his bow on the mound for the Pirates and his fast ones bothered his opponents considerably, but his teammates were unable to bring him support with their sticks.”2

Like the 900-plus other major leaguers who played in one major-league game and had looked forward to a second, Len Gilmore never got that opportunity. He went to spring training with the club in 1945 in Muncie, and as Opening Day approached he remained with the Bucs. It looked as if he might start the season in the Steel City. In fact, in a preseason article in which he named the Pirates as the team to beat in the National League in 1945, United Press sports editor Leo H. Petersen wrote that “the most promising of the rookies is Leonard Gilmore, who won 21 games while losing but five with Albany last season.”3 Unfortunately for Gilmore, Frisch did not agree with Petersen’s assessment and on April 9 decided that he was more impressed with Ken Gables, whom the Pirates had obtained from the Oakland Oaks of the Pacific Coast League. The Pirates sent Gilmore to Oakland to complete the deal.

Since Gilmore’s lone contest in the majors was a complete game, it put him on a couple of unique lists. According to John Dreker of PiratesProspects.com, among Pirates pitchers Gilmore pitched the most career innings without having a strikeout, as well as the most innings without a strikeout or walk.4 He is one of 27 major-league pitchers to throw a complete game in his debut and never have another complete game, and one of only three to go the distance in his only contest in the majors.

Back in the minors, the 27-year-old pitcher could not recapture the success he had with Albany, finishing with a 14-13 mark at Oakland in 1945. In 1946 he lost his only start for the Oaks before they sent him to the Milwaukee Brewers in the White Sox organization. Oakland’s manager at the time was Casey Stengel, who had a deep pitching staff and wanted to help Milwaukee because of “past favors” he felt he owed the club.5 After two shaky starts in Milwaukee (1-1, 5.62 ERA), Gilmore joined his third team in less than a month, winding up with the Cleveland Indians’ Oklahoma City farm team in the Double-A Texas League. It was that there Gilmore not only found a baseball home but also a home for life.

Gilmore played for Oklahoma City for the remainder of the 1946 campaign and for the following 2½ seasons. In 1946, he finished 11-12 with a career-low 2.32 ERA. The next season he was 12-10 despite spending two weeks on the bench with a sore arm.

In 1948 Gilmore, now 30, split his time between the bullpen and starting rotation, starting 20 times while pitching in relief 20 times. During that campaign Gilmore flirted with history, retiring 21 consecutive Dallas hitters through seven innings on August 5. He headed into the eighth with a chance to do what only one other Texas League pitcher had done in 53 seasons —pitch a perfect game. It was not to be: He lost the perfect game on an error, and then tired, surrendering five runs in the inning and ending up losing, 5-1.6

Gilmore pitched in 13 games for the Indians in 1949, then split the remainder of the season with Greenville and Texarkana in the Class B Big State League. He was out of the game in 1950 and finished his professional career in 1951 and 1952 in the Class D Sooner State League with the Seminole Ironmen, for whom he was 24-20 in two seasons.

Now 34 and out of baseball, Gilmore found that his time in Oklahoma had been of further benefit to him. In 1950 he joined the Oklahoma City Fire Department, where he eventually became a captain before retiring in 1970. He also met his wife, Virginia, while riding a streetcar in the city and they were married on September 5, 1950. They were together nearly 51 years, and had two daughters. Gilmore died in Oklahoma City on February 18, 2011, at the age of 93. Len Gilmore may have just been a footnote in the history of the game, but like the fictional Moonlight Graham and the other players who appeared in just one major-league contest, he was able to live his dream, even if it was only for a short time.

Sources

Berkeley Daily Gazette

Gettysburg Times

Milwaukee Sentinel

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Pittsburgh Press

Reading Eagle

The Sporting News

Archives.com

BaseballAlmanac.com

Baseball-fever.com

Baseball-Reference.com

Legacy.com

Pirates Prospects.com

Notes

1 “Pirate Rookies Tell of Greatest Thrills,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 11, 1945, 15.

2 Ed F. Balinger, “Bucs Take Second Place: Beat Phils, 9-1, Lose, 7-1,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, October 2, 1944, 15.

3 Leo H Petersen, “Pittsburgh Pirates Are Tagged as Team to Beat,” Berkeley Daily Gazette, March 29, 1945, 10.

4 John Dreker, “Pirates Leaders With Zero…,” Pirate Prospects.com, March 29, 2012.

5 Red Thisted, “Cullop Eyes Shakeup; Brews Invade St. Paul,” Milwaukee Sentinel, April 23, 1946, 7.

Full Name

Leonard Preston Gilmore

Born

November 3, 1917 at Fairview Park, IN (USA)

Died

February 18, 2011 at Oklahoma City, OK (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.