Sammy Samuels

In 1895, Sammy Samuels became the fifth Jewish player to appear in major league baseball and one of just six in the 19th century. Samuels’ brief stint with the St. Louis Brown Stockings was notable for his struggles at the plate and at third base. In the decades that followed, his poor play would be the subject of various anecdotes and jokes. Famed sportswriter Hugh Fullerton described him as both the worst hitter and fielder he ever saw play.

In 1895, Sammy Samuels became the fifth Jewish player to appear in major league baseball and one of just six in the 19th century. Samuels’ brief stint with the St. Louis Brown Stockings was notable for his struggles at the plate and at third base. In the decades that followed, his poor play would be the subject of various anecdotes and jokes. Famed sportswriter Hugh Fullerton described him as both the worst hitter and fielder he ever saw play.

Samuel Earle Samuels, who has been erroneously listed as Ike Samuels in baseball references1, was born in Quincy, Illinois, on February 20, 1874. His parents, Isaac T. Samuels and Jeanetta Aaronson, were both Prussian-German immigrants. Isaac had emigrated in 1860 to Adams County, Illinois, where he married Jeanetta in 1861. The couple soon became parents to four daughters before Samuel was born. Isaac was a dry goods merchant in Quincy throughout the 1870s.

Little is known of Samuels’ early life in Quincy or how he got involved in baseball. The family appears to have relocated to Chicago sometime in the late 1880s. It seems that Samuels’ first entry into competitive baseball occurred in the Chicago City League, the Windy City’s top circuit for aspiring young players. A third baseman named Samuels can be found manning the hot corner for the Records in 1891 and the J.H. Walker and Myrtle clubs in 1892.

Samuels balanced his baseball aspirations with his educational pursuits. Some sources note that he attended Northwestern University and played for their baseball team, before enrolling at the Rush Medical College dental school in 1894.2 In 1895, Samuels joined the Rush college baseball team briefly in the spring3 before beginning his professional baseball career with the Rock Island club of the Eastern Iowa League. He was recruited to Rock Island by player-manager Harry Sage, who had played for Toledo in the American Association back in 1890.

Samuels’ debut for Rock Island was delayed by an injured hand that he suffered in a game for Rush. He made his first appearance on May 8, 1895, in an exhibition game with the fabled Page Fence Giants, arguably the top Black team in the country in 1895. Rock Island took the victory by a surprising score of 5-1, and Samuels was singled out for his strong play in the May 9, 1895 Rock Island Argus: “Samuels played his first game yesterday, holding down short. His position is third base, but he does well at short. He is a corker with the stick.”4

Samuels’ strong play continued into June, though the club’s fortunes were waning. Without enough money to pay salaries, the club disbanded on June 13.5 Samuels was thought to be negotiating with the Burlington, Iowa, team, but did not sign. He ended up in Streator, Illinois, a town southwest of Chicago, playing for a club called the Reds.

In the summer of 1895, the St. Louis Brown Stockings were a laughingstock. The once proud franchise was in the midst of total collapse. Winners of four consecutive American Association pennants from 1885-1888 under the ownership of Chris von der Ahe, the club’s fortunes turned for the worse upon joining the National League in 1892. The Browns had finished well under .500 from 1892-1894 and in 1895 were on pace for their worst record yet. The inept squad would finish 39-92-5 and employ four different managers.

The club was in turmoil and on the desperate hunt for young talent who might be able to right the ship. On August 3, 1895, they turned to Sammy Samuels, whose professional baseball experience consisted of one month with Rock Island of the low-level Eastern Iowa League. The enthusiastic Samuels would be making his debut in his adopted hometown of Chicago. He made his debut in the third inning, replacing Tommy Dowd at third base, after Dowd was moved to second to replace Joe Quinn, who’d suffered an injury. With this appearance, Samuels became the fifth Jewish major-league player, preceded by the Pike brothers, Lip and Israel, Nate Berkenstock, and Jake Goodman. He became the first Jew to play in the majors since Lip Pike had made a token appearance at age 42 for New York in 1887.

Samuels played errorless ball, including several tough plays, and got one hit in his two at-bats off Chicago ace Bill Hutchison. His base hit was just one of four that St. Louis could muster that day in a 6-0 loss. His steady debut was enough to earn him a spot in the starting lineup the following day.

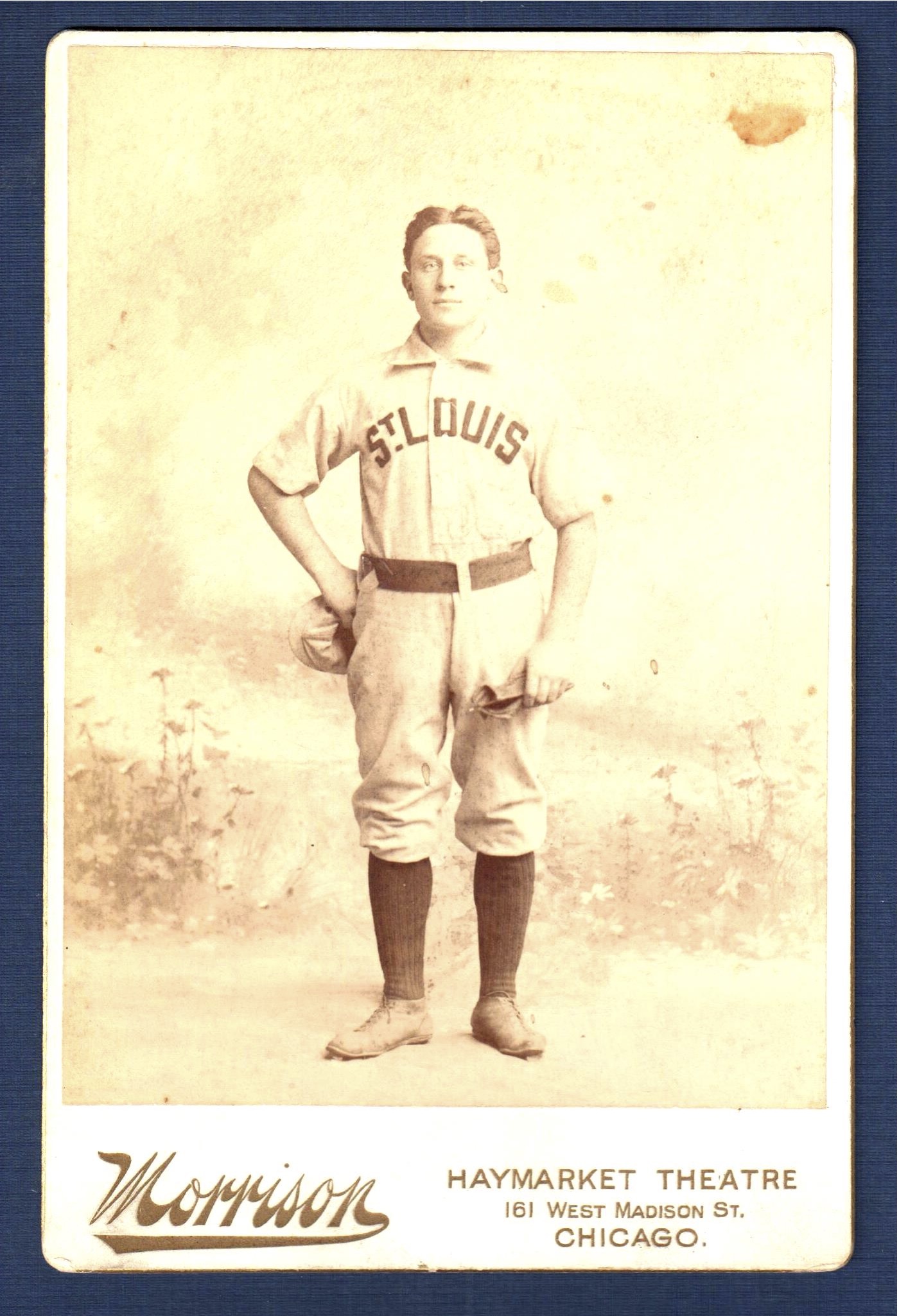

During this first series in his adopted hometown, Samuels made his way to the Morrison photo studio at the Haymarket Theatre to be photographed proudly in his St. Louis road uniform. The resulting cabinet image shows a striking young man, undoubtedly living his very best life. He was a major-league ballplayer, and no one could take that away from him.

On August 4, the young third baseman was held hitless, but played an outstanding defensive game, handling five chances without an error, in a 3-2 loss to Chicago. He was described as a “jewel” by the St. Louis Globe Democrat, which noted that his day’s work was excellent.6 St. Louis traveled to Pittsburgh, with Samuels going 1-for-5 and again playing errorless ball in a St. Louis victory on August 5.

On August 6, the first cracks appeared in Samuels’ defense, as he made two errors in an 11-2 loss to Pittsburgh. The following day, the Browns were drubbed 18-1, with Samuels making another error while going hitless. The Browns traveled to Cincinnati, where they were blown out again and Samuels made another error at third. On August 10, Joe Quinn stepped down as manager, to be replaced by a St. Louis turfman named Lou Phelan. Samuels’ struggles on defense combined with his poor hitting had started to draw ire and may have played a role in Quinn’s resignation. The Chicago Tribune noted that Quinn had been blamed for Samuels’ poor work, despite the fact that owner Chris von der Ahe had signed the rookie.7

Samuels sat out the Browns’ 7-7 tie with Cincinnati on August 11, with the Pittsburg Press noting that the rookie was “quite weak on hard hit balls and fails to bat up to the league gait.”8 As a result of his struggles, Samuels was sent back to St. Louis to join the club when they returned home on August 16. He made his home debut against last place Louisville, getting one hit in three at-bats and playing a rare errorless game, as the Browns won 8-5 to snap an eight-game winless streak.

The Browns won their next two games against Louisville, though Samuels made another four errors in the contests. The club then traveled east to New York, with Samuels continuing his erratic play. On August 23, his poor performance at third led to a St. Louis Post-Dispatch headline of “Samuels’ Fault: The Little Third Baseman Lost the Game for the Browns.”9 (Samuels was listed as 5-feet-7 and 165 pounds.) He made a throwing error in the second and then dropped a throw from catcher Heinie Peitz that led to a New York run. Another miss on a Peitz throw later in the inning led to a second New York run. The final score stood 7-4 for New York as a result of Samuels’ “manifold errors.”10 The St. Louis Globe-Democrat charitably noted that his struggles owed to lack of confidence rather than a lack of ability.11

Samuels was sent back to St. Louis once again, where he reportedly had many good stories to tell about the road trip. He played sporadically throughout September at home and his inability to handle clean chances at third base and shortstop continued. The Browns’ and Samuels’ dismal season came to a close on September 28 at home. An 18-2 slaughter at the hands of Pittsburgh was partially instigated by another two errors for Samuels.

In 24 contests with St. Louis, the 21-year-old third baseman, with only a modicum of pro experience, made 17 hits in 83 at-bats, good for a lowly .230/.278/.257 batting line. In the field, Samuels was even worse. In 21 games at third base, he made 20 errors and fielded just .750 in a league where the average third baseman fielded .872. His work at shortstop was somehow even more of an embarrassment. In three games, he made four errors on 11 chances, for a .636 fielding percentage against a league average .899.

Despite these marks, the Browns saw fit to reserve Samuels for the coming season, though he was involved in trade rumors involving the Minneapolis club of the Western League.

Samuels spent the off-season as a regular visitor to the office of Bill Phelon, the Chicago-based correspondent for the Sporting Life, one of the nation’s leading weekly sporting papers. Samuels was happy to share stories and provide gossip, on more than one occasion getting into trouble for his loose lips. In December 1895, he responded to rumors that one-time Brown Stockings third baseman Arlie Latham was going to replace him for the coming season. He told Phelon, “I tell you right now that Arlie Latham will never play third base for St. Louis…I will play that bag and there will be no competitors once I get started.”12

In January 1896, perhaps sensing that confiding in Phelon was a mistake, Samuels wrote into the paper to deny having spoken ill of Latham or having been a regular visitor of the Chicago sportswriter.13 His letter earned him the derision of Phelon, who jokingly noted that Chris von der Ahe was going to employ Samuels as a letter writer from the club.

Samuels was let go by St. Louis and began a three-year odyssey through multiple minor leagues in which he played for over a dozen teams – an astonishing seven in 1896 alone. He began that year with Springfield of the Eastern League but was released in late April after a handful of games. He then joined a club in Bangor, Maine, and left after a week. He went back to Chicago and appeared briefly for the Rush Medical College before being recruited to join his hometown Quincy club of the Western Association in May. He struggled in a short stint, including making six errors in one game. He then reappeared to play seven games in the Virginia League with the Roanoke Mountaineers and was given a one-game trial with the Hampton Clamdiggers. He evidently returned home to Chicago in September and was given a trial by the Cleveland Spiders in an exhibition game against the local Whitings on September 13, 1896. He made a hit but committed a costly error that allowed three runs to score. He was not given another look.

Samuels’ nomadic ways continued in 1897. He was signed by Indianapolis of the Western League but was released in mid-April prior to the season. He then joined the Dayton Old Soldiers of the Interstate League in mid-April and lasted until the start of May. Perhaps to hide his Semitic heritage, he began taking on the alias of S. E. Sanders or Saunders.14 It seems more likely, however, that he sought to hide his frequent releases and obscure his reputation as a light-hitting, poor-fielding third baseman. Under his new name, he signed with Fort Wayne of the same league. He was with the club just long enough to be included in a team photo in the June 6, 1897, issue of the Fort Wayne Sunday Gazette, but was released not long after. He maintained his alias with the Youngstown, Ohio, club, which the local sportswriter dubbed the “dumping place for all ambitious third basemen.”15 Samuels, the club’s sixth third baseman that year, did little to ingratiate himself with the locals. He lasted just two weeks and earned his release in mid-July.

He was reported to have signed with the Wheeling, West Virginia, club in the same circuit, but does not appear to have played for them. His next stop was in Burlington, Iowa, of the Western Association, where a Quincy scribe noted derisively that Samuels “stopped all that did not get by him.”16 He was released in mid-August, having compiled a .200 average in 31 games. This was his final stop in 1897.

Despite his wandering and frequent failures, Samuels once again found work in 1898. In February, he was reported to have signed with a team in Texas, though that appears not to have come to fruition. The Fort Wayne News still bristled over his terrible play there in 1897 and described him as a “fake third baseman.”17 In the March 26, 1898, edition of Sporting Life, a complaint from Samuels under the pen name of S. E. Sanders appeared. Samuels decried his absence from the Interstate League’s official list of batting averages, noting that he had hit .300 in 25 games with Fort Wayne and led the team in batting until he hurt his ankle and was released.18 Existing box scores do not show Samuels to have demonstrated much hitting prowess, and his release stemmed from poor play rather than injury.

One can speculate that Samuels was a frequent letter writer and not afraid of embellishing the truth. In the 1890s, it was common for players to write clubs and various newspapers to advertise their skills and availability. Since we have a few examples of Samuels writing to Sporting Life, it seems very likely that he was boasting of his abilities to any and everyone. This would seem to be a key reason he could get opportunity after opportunity, despite failing each time. He appears to have been a speedy player and a good athlete, which may have helped him pass the eye test, but his futility at the plate and in the field during games quickly hastened his departure everywhere he played.

Samuels plied his trade in the Northeast in 1898, once again employing the alias of S. E. Sanders or Saunders.19 He started the year with Auburn of the New York State League. A note about his signing mentioned that he had appeared in the Iron and Oil League in Pennsylvania and hit .340 in 1897.20 Neither of these points is true; Samuels was almost certainly the source of misinformation.

He debuted for Auburn in mid-May but lasted just two weeks and was released at the end of the month. He joined the rival Oswego club but lasted just two days. It was noted that he had played a “yellow game” and would have to improve greatly to stay on.21 He then joined Utica for another brief stint before being released once again. By the end of June, he had appeared for three different clubs in the circuit.

Samuels was reported to have joined Bridgeport in the Connecticut League, but ended up with New Britain, where he rejoined his old rival, Arlie Latham. He lasted with that club for a month, somehow also earning one-game trials with Derby in early July and Newark of the Eastern League on July 9. Samuels displayed his pugnacious side when he got into an altercation with team manager Claude Gilbert in late July. Samuels was talking to a local store owner named F. H. Allis, when Gilbert came by and mockingly asked Samuels if he was telling the shopkeeper about “his troubles?” Samuels responded by saying that he “would have no troubles if he was paid his salary.”22 Gilbert said he owed Samuels no money and the ballplayer responded by punching Gilbert, knocking a tooth loose before fleeing down the street and taking a car back to Hartford.

That incident ended his time in New Britain, but Samuels soon joined the Norfolk Jewels of the Atlantic Association. Preceding his arrival, a note appeared in the local papers claiming that Samuels had been the captain and third baseman for New Britain, hitting .397 and fielding .937.23 In all likelihood the source was Samuels. He lasted with the club until mid-September and appears to have returned home to Chicago for a couple of token appearances in the Chicago City League.

1898 would prove to be Samuels’ final season in professional baseball. In four years, he appeared for 17 different pro clubs, along with stints with Rush Medical College and for several Chicago City League clubs.24 The Waterbury Evening Democrat summed up his career by noting that he belonged in a “unique diamond society” of ballplayers who “might organize as a band of men who, with malice afterthought, cheated the American public and alleged club managers into thinking they could play baseball.”25 It seems that his reputation had finally caught up to him.

Samuels played semipro ball in and around Chicago in 1899 and 1900. He married Sadye Brousky on April 30, 1900. A year later, he made a last-ditch effort to play pro ball and was briefly rostered as Sammy Saunders by the Allentown, Pennsylvania, club. Evidently, though, he settled into post-baseball life in Chicago.

Samuels does not appear to have completed dental school – Rush Medical College had no record of his graduation. Yet despite his lack of a degree, Samuels can be found listed as a dentist in Chicago in the 1900 Census. By 1910, Samuels and his wife had relocated to New York City, where they lived the rest of their lives without having any children.

Samuels found work selling dental equipment for a man named Wallace Sadler, acting as the firm’s representative to Columbia University’s College of Oral and Dental Surgery, a role he held until the mid-1920s. The one-time ballplayer’s career would occasionally be referenced in the New York papers for its futility as well as his Jewish ancestry. One example came in Hugh Fullerton’s account of Game Two of the 1912 World Series, which ended in a 6-6 tie between New York and Boston. Fullerton claimed that Giants shortstop Art Fletcher, who committed three errors in the contest, was the worst fielder he ever saw save for Sammy Samuels.26 In a 1921 column, Fullerton wrote that Samuels was the worst hitter ever to appear in the major leagues.27

The 1930 Census showed Samuels as a salesman for an advertising company. By 1942, he was working for a Newark-based publishing company. It is not surprising that a player noted for self-promotion would end up in sales.

In 1951, the New York Daily News offered $50 to any former big-league players who could prove they had not been included in the recently published Turkin and Thompson’s Baseball Encyclopedia. Samuels showed up to the office to claim his $50 and was informed that he was already in the book. The encyclopedia included his birth year as 1876, making him 75 years old, but Samuels protested that he was actually born in 1879. A week later, Samuels returned to the office to ask where he could buy the book, since he needed proof that he was 75 in order to qualify for Social Security.28

Sammy Samuels died on February 22, 1964, in New York and was buried in Zion Gardens Cemetery in Chicago, Illinois. His legacy as a Jewish pioneer in 19th-century baseball has been overshadowed by his futility at bat and in the field. His odd career reveals the opportunities that one can receive by combining unwavering self-confidence and a knack for self-promotion.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Russ Case c/o RLC Protection Trust for use of the Sammy Samuels cabinet photo.

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Paul Proia.

Sources

The Sporting Life Collection, courtesy of LA84.org

Notes

1 The source of the name “Ike” is unknown. It was not used by Samuels or sportswriters at any point during his career or after.

2 “Baseball at Rush Medical,” Chicago Inter Ocean, March 31, 1895: 14. It is noted herein that Samuels was trying out for third base role at Rush Medical College and had played with Northwestern University.

3 “Most All Captains,” Chicago Tribune, March 26, 1895: 11. It is stated herein that, “Samuels at third is an old Northwestern man. He is pretty sure to play that position.”

4 “Grand Stand Gossip,” Rock Island (Illinois) Argus, May 9, 1895.

5 Rock Island Argus, June 14, 1895.

6 “Colts Took Three Straight,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 5, 1895: 9.

7 “Lewis Phelan Succeeds Joe Quinn,” Chicago Tribune, August 11, 1895: 4.

8 “Baseball Brevities,” Pittsburg Press, August 12, 1895: 5.

9 “Samuels’ Fault: The Little Third Baseman Lost the Game for the Browns,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 24, 1895: 5.

10 “Breitenstein Again Beaten,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 24, 1895: 6.

11 “Breitenstein Again Beaten.”

12 W.A. Phelon, Jr., “The Irrepressible Comedian,” Sporting Life, December 28, 1895: 8.

13 “Justice for Samuels,” Sporting Life, January 11, 1896: 1.

14 “Sporting Notes,” Ft. Wayne News, June 25, 1897: 3.

15 “Another One Arrives,” Youngstown (Ohio) Vindicator, June 23, 1897: 3.

16 “Base Ball Notes,” Quincy (Illinois) Morning Whig, July 18, 1897.

17 “Sporting Notes,” Fort Wayne (Indiana) News, February 1, 1898: 3.

18 “News and Comments,” Sporting Life, March 26, 1898: 5.

19 “New Britain News: New Players Secured,” Hartford Courant, June 28, 1898.

20 “Farrell’s Selection of Baseball Talent,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, April 15, 1898: 14.

21 Auburn (New York) Bulletin, June 6, 1898.

22 “Manager Gilbert Assaulted,” Hartford Courant, July 27, 1898: 10.

23 “Have Signed New Men,” Norfolk Virginia-Pilot, August 12, 1898: 2.

24 “Most All Captains,” Chicago Tribune, March 26, 1895: 11.

25 “World of Base Ball,” Waterbury (Connecticut) Evening Democrat, April 13, 1899: 12.

26 “Giants Were Lucky, Fullerton Declares,” New York Times, October 10, 1912: 3.

27 “Fullerton’s Column,” Yonkers (New York) Herald Statesman, December 10, 1921: 9.

28 Jimmy Powers, “The Powerhouse,” New York Daily News, December 4, 1951: 84.

Full Name

Samuel Earl Samuels

Born

February 20, 1874 at Quincy, IL (USA)

Died

February 22, 1964 at New York, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.