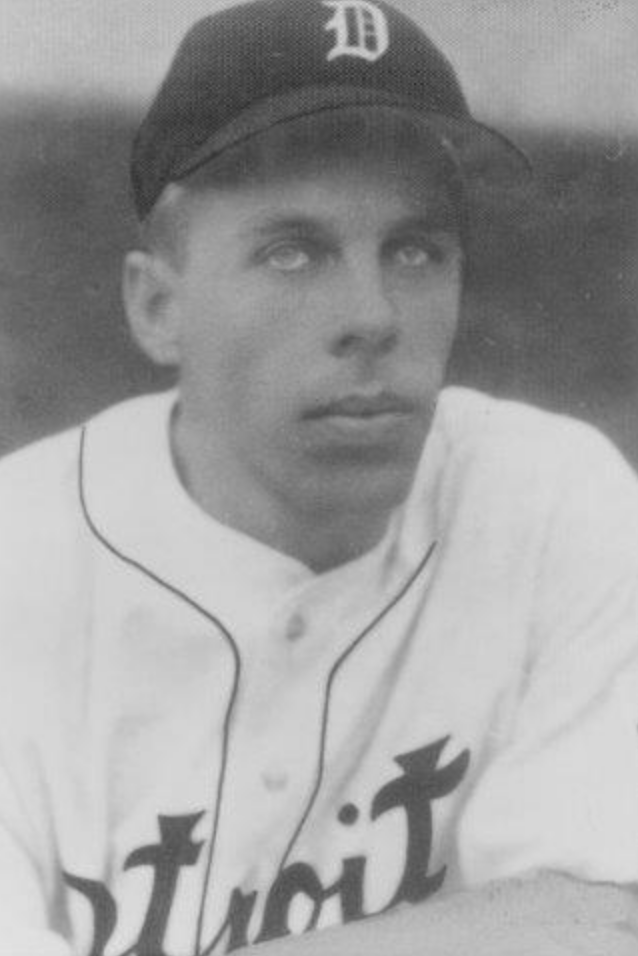

Bob Maier

Bobby Maier would have been forgiven for harboring some bitterness toward manager Steve O’Neill and the Detroit Tigers. For most of 1945, the 29-year-old rookie had started at third base for the Tigers, doing a consistent if unspectacular job at the plate while proving perhaps less reliable with the glove. But as Detroit entered the stretch run, desperate to hold off the Washington Senators, Maier found himself on the bench in favor of Jimmy Outlaw. That left Maier a spectator for most of the final seven games of the regular season as the Tigers wrapped up the American League pennant, and limited him to a single pinch-hitting appearance in seven World Series games against the Cubs.

Bobby Maier would have been forgiven for harboring some bitterness toward manager Steve O’Neill and the Detroit Tigers. For most of 1945, the 29-year-old rookie had started at third base for the Tigers, doing a consistent if unspectacular job at the plate while proving perhaps less reliable with the glove. But as Detroit entered the stretch run, desperate to hold off the Washington Senators, Maier found himself on the bench in favor of Jimmy Outlaw. That left Maier a spectator for most of the final seven games of the regular season as the Tigers wrapped up the American League pennant, and limited him to a single pinch-hitting appearance in seven World Series games against the Cubs.

Looking back more than 40 years later, though, Maier gave no hint of regret for not being able to play a larger role when it mattered the most. “I had nothing against Steve for sitting me down,” he said. “I wasn’t playing up to snuff. I had no hard feelings toward Jimmy, either. He was a good ballplayer, a hustler.”1 Two traits Bobby Maier could also claim for himself.

Robert Phillip Maier (pronounced MYER) was born on September 5, 1915, in Dunellen, New Jersey. His father’s parents, Joseph and Katherine, were born in Germany and emigrated to New Jersey in the mid-1850s. They eventually settled in Dunellen, where Joseph opened the Park Hotel on North Avenue. Their son Joseph was born at the hotel on June 14, 1873,2 and eventually took over as proprietor after his father died in 1892.3 Joseph married Annie E. Doyle in February 1899, and the couple had three children before Annie died of pneumonia six years later at the age of 29.4 In 1910 Joseph married Anna E. Pfister – a union that would produce nine more children, including Robert.

Bobby got his start in baseball in its most basic form, employing a broomstick and tennis ball to play for hours on end with his older brother Eddie.5 Their father died in March 1930, six months shy of Bobby’s 15th birthday. When the census taker came around a month later, she found Anna Maier and 11 others – nine children and two stepchildren, ranging in age from 5 months to 30 years old – under the same roof at 339 Dunellen Avenue.6

Everyone chipped in to keep the household afloat. Bobby played semipro ball while still in high school, and also worked nights setting up pins at the Elks bowling lane. He didn’t go out for his high-school team at St. Peter’s until his senior year.7

In 1937 a friend from semipro ball recommended Maier to Joe Cambria, the legendary Washington Senators scout who pioneered player development in Cuba. Cambria also owned several teams in the minors and Negro leagues at various junctures, including, for a time, Trenton of the Class A New York-Penn League. Cambria invited Maier to work out with Trenton on the final day of the 1937 season, and allowed him to dress for the ensuing doubleheader. Statistics at baseball-reference.com don’t have Maier participating in any games for Trenton that year, but he said he played third base and went 1-for-3 in the nightcap – earning a contract for 1938 along the way.8

“I can’t remember anything I didn’t like about the minor leagues,” said Maier, who was thrilled to make baseball his full-time summer occupation.9 Beginning in 1938, after signing for $75 that February,10 Maier spent four seasons playing for Cambria’s team in Salisbury, Maryland, in the Class-D Eastern Shore League, playing third base, second base, or the outfield depending on the makeup of the team.

Salisbury had won the pennant the year before and repeated in Maier’s first season there.11 Then, as now, the minor-league lifestyle was far from glamorous. Maier never made more than $100 a month while playing for Salisbury, though he acknowledged that the team stayed in “pretty good hotels” on the road to accompany the 50-cent per diem granted to the players.12

There was, however, a limit to how much they would let Cambria squeeze out of them. In the final week of the 1940 season, the Salisbury players declared a strike, demanding back pay before taking the field again. Cambria acquiesced, but sold the club to Reuben Levin after the season.13 Levin, a lawyer who lived in Bennington, Vermont,14 apparently took a liking to Maier. When Salisbury’s player-manager, Johnny Wedemeyer, joined the Navy in June 1941, Levin appointed the 25-year-old Maier to replace him.15

Consistency was Maier’s hallmark during his Salisbury stint. He hit either .285 or .286 three of his four seasons there, with the exception an impressive 1939 campaign that saw him hit .326 with 33 doubles and a career-best 11 home runs in 119 games. But 1941 was the end of the line there. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor propelled the country into war that winter, numerous teams – and entire leagues – disbanded. The Eastern Shore League was among them, and wouldn’t re-emerge until 1946.

For the teams that remained, the rosters began to take on a different look as well. As increasing numbers of young men volunteered for or were drafted into the armed forces, baseball naturally was depleted along with other industries and professions. With more and more men called away, teams at all levels were forced to get by with the too old, the too young, the not quite good enough – after a while, just about any deferment would do.

When Bobby Maier was called before his draft board in Newark shortly after America entered the war, he was, to his surprise, classified 4-F – not acceptable for military service – after undergoing a physical. A hernia he never knew about kept him out of World War II.16 But the war’s effects on major-league rosters ultimately landed him somewhere he never dreamed of being: the World Series.

But Maier couldn’t see that in his future as the 1942 season began. Left without a team, he had latched on with Hagerstown of the Class-B Inter-State League near the end of spring training. The Owls were a Detroit affiliate, so Maier had a new organization to impress. And for the first and only time in his professional career, he fell flat.

Playing mostly at third base for manager Fred “Dutch” Dorman, Maier hit .222 and compiled only 17 extra-base hits while playing in all 137 games. A lack of alternatives kept him around, though, and it was a good thing – 1943 proved to be the season of Maier’s life.

Dorman had jumped to the Wilmington club for 1943 and Eddie Phillips, who had reached the majors as a journeyman catcher, was installed as Hagerstown’s new manager. Maier quickly established himself as one of Phillips’s best hitters and often held down the third spot in the Owls’ productive batting order. Nine players who spent at least part of 1943 with Hagerstown ended up hitting over .300 that year, with Maier leading the way at .363. He racked up 52 doubles, tops among all minor-league players, to go with 12 triples and 7 homers.

More impressively, Maier put the finishing touches on those numbers while pulling player-manager duty once again. Phillips abruptly resigned as manager on July 27, and owner Oren E. Sterling tabbed Maier to replace him. The Hagerstown Daily Mail had no qualms with the decision, noting that “not only is he a great player but is a popular one with his teammates as well as the fans. A handy man if ever there was one, Bobby has played about every position there is on the team and always can be counted on to do his utmost.”17

Maier made the league’s all-star game the following month, starting in center field, and was selected to the Inter-State League all-star squad at the end of the season as a utility player. (Impressive as Maier’s season was, he couldn’t displace 20-year-old George Kell of Lancaster from the third-base spot on the team. The future Hall of Famer hit .396 and legged out 23 triples, becoming the lone unanimous choice in balloting of the league’s managers and writers.18)

While Kell would jump to the majors in 1944 and never look back, Maier’s showing was strong enough to earn him a look at the minors’ highest level. He signed with Buffalo of the International League that March and immediately became manager Bucky Harris’s starting third baseman. Though Maier moved around the diamond throughout his career, he always found a way to get on the field. When he arrived in Buffalo he was riding a streak of 631 consecutive games played that stretched back to his time with Salisbury,19 but he nearly saw it come to an end in the season’s opening weeks.

In a May 3 game in Buffalo, Baltimore Orioles pitcher George Hooks beaned Maier near the temple; Maier had to be carried off the field.20 “I don’t know what happened, but it was an accident,” Maier said years later. “No batting helmets back then. After I was hit I couldn’t see, but I could hear everything that was going on until they got me into the clubhouse.”21

Remarkably, Maier’s ironman streak lived on. The Bisons and Orioles had a scheduled off day the following day, and the next two games were rained out. When Buffalo finally returned to the field, Maier was right there with them. The Orioles and Bisons met again in September in the playoffs, with Baltimore winning in the seventh game to advance and face Newark for the International League championship. Bobby Maier, however, was about to take a big step up.

Toward the end of Buffalo’s season, rumors circulated that Detroit might purchase the contracts of Maier and pitcher Walter Wilson from the Bisons for the stretch run, but those hopes never materialized. The two were, however, invited to the Tigers’ training camp in Evansville, Indiana, the following spring.22

Expectations were unusually high for a career minor leaguer walking into an unfamiliar camp. Steve O’Neill’s biggest worry heading into 1945 was finding a replacement for hard-hitting left fielder Dick Wakefield, who was off to the Navy after a pair of eye-opening seasons in Detroit. O’Neill’s initial plan was to try to use Maier in that spot. Wakefield was a renowned athlete, 6-feet-4 and 210 pounds, and he had hit .355 with a 1.040 OPS (on-base percentage plus slugging average) in 78 games the previous season as a 23-year-old. Maier, a 5-foot-8, 180-pounder, didn’t fill out the baggy flannel uniform as impressively, but O’Neill was willing to give him a shot.

Maier hit well in spring intrasquad games, prompting O’Neill to note to the newspapermen, “The fellow looks pretty good up there. He runs well, too, and has a good arm.”23 That was more than the manager shared with Maier, apparently. He was never actually told he made the team; he just inferred it when he made it all the way to the end of spring training.24

O’Neill’s master plan, however, wouldn’t last long. Maier started in left field the first three games of the season, against the St. Louis Browns in St. Louis, but then disappeared in favor of 41-year-old Chuck Hostetler. For five games Maier sat, reappearing in left to start the second game of a doubleheader against the Cleveland Indians on April 29. After the game, the Tigers traded infielders Don Ross and Dutch Meyer to the Indians for outfielder Roy Cullenbine. “As far as I’m concerned,” said Maier, “that was the best trade Detroit ever made.”25 For three games after the deal, O’Neill started Red Borom at third and in the leadoff spot. On May 6 Maier took over at the hot corner. There he stayed, starting 102 consecutive games at the position through August 21.

The Tigers, meanwhile, were rolling. After lagging a game behind the Browns for the American League pennant in 1944, they were determined to finish 1945 on a higher note. Led by left-hander Hal Newhouser, who would win his second consecutive AL Most Valuable Player award that year, the Tigers established themselves as an early contender in what would prove to be the final season of watered-down wartime baseball.

Maier and the others who owed to the war their shot at the majors surely knew what was coming. During the summer, while the war was still on, Hank Greenberg returned to the Tigers lineup. Playing in a big-league game for the first time since May 6, 1941, Greenberg was the cleanup hitter for the first game in Detroit’s July 1 doubleheader against the Philadelphia Athletics. His home run helped the Tigers down the A’s 9-5 before a crowd of 47,729 at Briggs Stadium.

Maier’s batting average rarely strayed from the .260s throughout the summer (he finished at .263), and a rare 3-for-4 day against the Browns on August 28 provided another highlight: his lone home run in the majors. But Maier’s most notable contribution to the stretch drive came with his feet.

Detroit had lost two of three games in a mid-September series in Philadelphia – both in walk-off fashion – and faced one more contest, on the 14th, against the bottom-dwelling A’s before beginning a crucial five-game set against the second-place Senators. The game was scoreless when Maier opened the top of the fifth inning with a single to deep shortstop. Paul Richards did the same and pitcher Les Mueller bunted them over before Joe Hoover was intentionally walked to load the bases. With O’Neill’s son-in-law, second baseman Skeeter Webb, at the plate, the manager called for a squeeze play. But the A’s pitched out, and Maier had no chance to beat the delivery home. Catcher Buddy Rosar came up the line to make the tag, and Maier, “some ten feet from the plate, stopped suddenly, then dived under and somewhat around Rosar,” who “clearly” missed the tag. After Maier crawled the rest of the way to the plate, Rosar howled that Maier had been out of the baseline, but umpire Art Passarella disagreed. The next inning saw a torrential downpour swamp Shibe Park, and the game ultimately was called, reverting to the five-inning final score of Detroit 1, Philadelphia 0.26

The Tigers swept a doubleheader from the Senators in Washington the following day and went on to secure the pennant on the final day of the season, when Greenberg’s grand slam in the top of the ninth beat the Browns. Maier didn’t play in that game, the first in a doubleheader. He was slated to start the second game,27 but it was rained out. He would make just one more trip to the plate as a major leaguer, but it would come on the game’s biggest stage.

Heading into the World Series between the Tigers and Chicago Cubs, few were overwhelmed by the collection of talent about to be on display. The Associated Press, for instance, sniffed that the Tigers, “to put it mercifully, have strictly a wartime infield.”28

Maier would not be a part of it. Apparently due to concerns about Maier’s defense (he made 25 errors in 124 games), O’Neill gave Jimmy Outlaw the starting nod at third base throughout the Series. Outlaw, who had spent most of the season in the outfield, played every inning of the seven-game Series at third, going 5-for-28 (.179) at the plate.

Maier’s lone moment in the spotlight came in the sixth inning of Game Six at Wrigley Field. The Tigers led the Series, three games to two, but they trailed 4-1 in the game when O’Neill sent Maier up to hit for catcher Paul Richards with Cullenbine on second and two out. Maier ripped a liner off pitcher Claude Passeau’s glove, and was safe with an infield single. With runners on the corners, John McHale batted for Detroit pitcher George Caster and struck out looking to end the threat. Backup catcher Bob Swift replaced Maier in the lineup in the bottom of the sixth, and the Cubs went on to win 8-7 in 12 innings. But Detroit closed it out the next day behind Newhouser, securing its second World Series title.

A special train took the champions back to Detroit, and Maier was a happy bystander to the Tigers’ revelry. “There were just two of us – Les Mueller, a pitcher, and me – who didn’t drink. But we went down and watched the others enjoying themselves.”29 Maier didn’t have much of a hand in the World Series win, but his efforts were noticed. The Sporting News named him the third baseman on its all-star freshman team but noted that he wasn’t likely to have a starting job when 1946 rolled around.30

That fall Maier went back to the offseason job he had held for years, working as a pressman at Dunellen’s biggest employer, the Art Color Printing Company, which produced 10 million magazines per month. His older brothers William and Edward had worked there as well,31 and Maier fell easily back into his offseason routine.

Maier’s salary for 1945 was $4,500, making his World Series winner’s share of $6,445 especially welcome back home. When it came time to negotiate a contract for 1946, the Tigers insisted on keeping Maier at the same rate. Neither side budged, and the Tigers eventually gave up on Maier and returned his contract to Buffalo. Maier had no interest in returning to the Bisons, so the Tigers released him altogether, ending his career in Organized Baseball. “I had no regrets,” he said. “I had a good job at home, and I was getting almost $100 a week playing semipro ball.”32

Having played in the majors made Maier something of a marquee attraction on the semipro circuit, which regularly included games against Negro League teams. In June of 1946, Maier’s Madison Colonels visited Kingston, New York, for a night game and the local Daily Freeman touted Maier as “one of the season’s finest white attractions.”33

Maier continued to play on the semipro circuit with the Colonels through at least 194834 while working at Art Color and later Twin City Press in nearby North Plainfield.

When the Tigers returned to the World Series in 1984, the Associated Press did a short story on Maier, then 67 and working as a crossing guard for Dunellen schools – and cheering for his old team. “I wouldn’t have traded it for anything in the world. It was something you never forget,” he said. “I played one year and won the pennant and the World Series. You can’t do much better than that.”35

Bobby and his wife, Mary, remained in New Jersey until their deaths, less than four months apart, in 1993. Bobby Maier died on August 4 of that year in South Plainfield. He was 77.

This biography originally appeared in “Who’s on First: Replacement Players in World War II” (SABR, 2015), edited by Marc Z. Aaron and Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 Bob Maier and Bill Benwell, Bobby Maier: A Baseball Memoir (pamphlet from 1992, in the holdings of the Dunellen, New Jersey Public Library), 10.

2 Dunellen Weekly Call, March 6, 1930.

3 Dunellen Weekly Call, March 27, 1913.

4 Dunellen Weekly Call, February 9, 1905.

5 Maier and Benwell, 1.

6 1930 US Census, via Ancestry.com

7 Maier and Benwell, 1.

8 Maier and Benwell, 2.

9 Maier and Benwell, 3.

10 Maier and Benwell , 2.

11 Brian McKenna. “Joe Cambria,” The Baseball Biography Project, accessed September 5, 2014.

12 Maier and Benwell, 3.

13 McKenna, “Joe Cambria.”

14 Roy Shudt, Times Record, (Troy, New York), February 25, 1941.

15 “Salisbury Indians Lose Manager,” Associated Press via the Washington Post, June 10, 1941.

16 Maier and Benwell, 13. (Maier reportedly underwent at least two additional draft physicals in the next few years, both of which confirmed his 4-F status.)

17 “Bobby Maier Succeeds Phillips as Manager of the Owls,” Daily Mail (Hagerstown, Pennsylvania), July 28, 1943.

18 “Davis and Maier Selected for Berths on Mythical Outfit,” Daily Mail, September 8, 1943.

19 Leo MacDonell, “Darkhorse Maier Cops Wakefield Garden Stall,” The Sporting News, April 12, 1945.

20 Randall Cassell. “Orioles Trim Buffalo, 11-5,” Baltimore Sun, May 4, 1944.

21 Maier and Benwell, 5.

22 Maier and Benwell, 6.

23 Greene, The Sporting News, April 5, 1945.

24 Maier and Benwell, 7.

25 Ibid.

26 “Tigers Win, 1 to 0, Scoring Lucky Run,” Associated Press via the New York Times, September 15, 1945.

27 Maier and Benwell, 10.

28 Associated Press via St. Petersburg (Florida) Evening Independent, September 27, 1945.

29 Maier and Benwell, 12.

30 Frederick G. Lieb, “Strongest All-Freshman Team Since ’41 Named,” The Sporting News, November 1, 1945.

31 1940 US Census, via Ancestry.com

32 Maier and Benwell, 12.

33 “Bob Maier, Former Tiger Infielder, Will Appear Here,” Kingston Daily Freeman, June 26, 1946.

34 “Cubans to Play Sunday,” New York Times, September 10, 1948.

35 “Crossing Guard Recalls His Days With Detroit Tigers in 1945 World Series,” Associated Press, October 12, 1984.

Full Name

Robert Phillip Maier

Born

September 5, 1915 at Dunellen, NJ (USA)

Died

August 4, 1993 at South Plainfield, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.