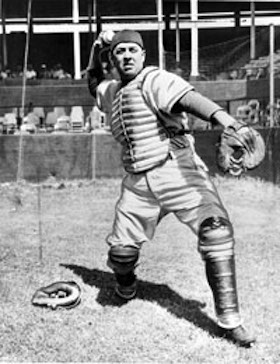

Buddy Rosar

He could be considered one of the most reluctant, or perhaps contradictory, players to have ever walked on to a ball field. In July 1942 Buddy Rosar wore out his welcome with the New York Yankees after bolting the team to sit for a police department entrance exam (anticipating postcareer employment) and to visit his newborn son; in 1944 and 1945 he refused to report to spring training, hinting strongly at retirement, in order to continue working at a hometown factory. (This could be chalked up as patriotic zeal; he was working in a weapons materiel plant in Buffalo, New York, during World War II.) Yet on many occasions throughout his playing career Rosar expressed a desire to remain in baseball among the coaching or managerial ranks. He was one of baseball’s finest ambassadors – attending drama lessons in 1948 to improve his techniques on the rubber-chicken circuit – and, when he chose to suit up, was one of the major leagues’ best catchers. A five-time All Star, Rosar was the fifth catcher in major-league history to hit for the cycle. Through 2015 his 54.81 caught stealing percentage trailed only HOF backstops Gabby Hartnett and Roy Campanella, and for many years Rosar held the major-league mark for having caught 147 consecutive games without an error. In 1959 another Hall of Famer, Yogi Berra, edged this latter mark by one game, and Rosar might hold the record today if not for an umpire’s questionable call.

He could be considered one of the most reluctant, or perhaps contradictory, players to have ever walked on to a ball field. In July 1942 Buddy Rosar wore out his welcome with the New York Yankees after bolting the team to sit for a police department entrance exam (anticipating postcareer employment) and to visit his newborn son; in 1944 and 1945 he refused to report to spring training, hinting strongly at retirement, in order to continue working at a hometown factory. (This could be chalked up as patriotic zeal; he was working in a weapons materiel plant in Buffalo, New York, during World War II.) Yet on many occasions throughout his playing career Rosar expressed a desire to remain in baseball among the coaching or managerial ranks. He was one of baseball’s finest ambassadors – attending drama lessons in 1948 to improve his techniques on the rubber-chicken circuit – and, when he chose to suit up, was one of the major leagues’ best catchers. A five-time All Star, Rosar was the fifth catcher in major-league history to hit for the cycle. Through 2015 his 54.81 caught stealing percentage trailed only HOF backstops Gabby Hartnett and Roy Campanella, and for many years Rosar held the major-league mark for having caught 147 consecutive games without an error. In 1959 another Hall of Famer, Yogi Berra, edged this latter mark by one game, and Rosar might hold the record today if not for an umpire’s questionable call.

Warren Vincent “Buddy” Rosar was born on July 3, 1914, the only child of Frank and Caroline E. (Fryer) Rosar, in Buffalo, New York. Very little is known of Frank Rosar. He was a plumber of French or French-Canadian ancestry born in Buffalo in 1887. Frank married Caroline in Ontario, Canada, when she was eight months pregnant with their son and reportedly died when Buddy was very young; the last presence of Frank is noted in the 1920 census, living with his mother apart from Caroline and his son. Far more is known of Caroline’s family, particularly her brothers Jack and Chris, who both played baseball professionally. It was these uncles who conferred the nickname “Buddy” on their red-headed nephew and steered him into sports. (The youngster was accomplished in football and basketball as well.) Growing up within blocks of the Buffalo Bisons’ ballpark, Buddy had a great deal of exposure to baseball. Though he pitched some at Buffalo’s East High School from an early age, Buddy’s primary position was catcher. In 1933, as a senior, Buddy led the East High Panthers to an undefeated season to seize the Cornell Cup, denoting the regional championship. He also excelled in semipro ball with the Buffalo Karts and in three years of American Legion play, leading the Legion team to state and sectional finals and serving as co-manager in at least one of the three years. In the spring of 1933, shortly before his high-school graduation, the International League Bisons offered Rosar a contract to play for the hometown squad.

Rosar spurned the Bisons’ overture, signing instead with Yankees scout and former major-league hurler Gene McCann in the fall. A certain amount of myth surrounds Rosar’s discovery. One report states that Buffalo native Elizabeth McCarthy, the wife of Yankees manager Joe McCarthy, came upon the catching phenom in 1933 and quickly alerted McCann to her finding. A more fanciful tale tells of McCann resting by a pond when a baseball hit by Rosar from a faraway field landed in the water, with the resulting splash soaking the scout; the prodigious blow supposedly prompted McCann to sign the youngster on the spot. More likely, McCann appears to have found Rosar catching Buffalo Knights of Columbus (and future Boston Red Sox) pitcher Emerson Dickman during a charity game at Bisons Stadium. The late-autumn signing delayed the launch of Rosar’s career until May 3, 1934, when, in his first swing as a professional with the Class A Binghamton (New York) Triplets, Rosar lined a home run against Elmira Red Wings’ hurler Winslow White. Rosar continued hitting at a .500 pace in his next seven at-bats before a fractured vertebra – an injury initially sustained in a high-school basketball game – ended his stay with the Triplets. When Rosar recovered, he was reassigned to the Class C Wheeling (West Virginia) Stogies in the Middle Atlantic League. Rosar played in 41 games before the injury resurfaced in July, ending his first professional season.

Described as a player “destined to go high,”1 Rosar was assigned in 1935 to the Class B Norfolk (Virginia) Tars. Leading the Piedmont League with 26 homers, his .347 average, 29 doubles, and 276 total bases all placed among the circuit leaders. Perhaps more significantly, Rosar developed defensively under the Tars manager, former major-league catcher Bill Skiff, especially with an arm that had initially been deemed as merely fair. In 1936 Skiff took the 21-year-old catcher with him as they advanced to Binghamton. Besides handling the bulk of play behind the plate, Rosar, thanks to a rash of injuries to his teammates, saw occasional duty at the infield corners. Though the homers dropped off precipitously – a line-drive hitter, Rosar hit home runs in double digits in just one more season – his .344 average and 35 doubles again placed among the league leaders. Surprisingly, the rotund, generally slow-footed catcher also managed to swipe 14 bases.2

In 1937 Rosar was promoted to the Newark Bears and, in his first game at the Double-A level, launched two homers against former Yankees hurler Hank Johnson. With a roster that included slugger Charlie Keller and future HOF second baseman Joe Gordon, the 1937 Bears won the International League pennant by 25½ games and eight decades later are still considered one of the greatest minor-league teams ever.3 Injuries to Rosar and future Cincinnati Reds backstop Willard Hershberger – both were sidelined with split fingers in a June 8 game against the Baltimore Orioles – resulted in a season-long platoon. When these injuries prevented Rosar from catching, Bears manager Ossie Vitt did everything he could to keep Buddy’s hot bat (.332 with 8 homers in 232 at-bats) in the lineup. The youngster proved extremely productive as a pinch-hitter – 7-for-8 – and there is some indication that Vitt placed Rosar in the outfield on occasion.

Seemingly poised to unseat Joe Glenn or Arndt Jorgens as the 1938 backup to future HOF catcher Bill Dickey, Rosar was slowed in his advance after he sustained another split finger in spring training; he was reassigned to Newark. After missing the first 23 games of the season, in his first game back he launched a homer against Toronto’s Earl Caldwell. He followed with a first-inning grand slam off Buffalo’s Herman Fink in his first road at-bat. But injuries continued to mount, including a two-week layoff with a concussion after Jersey City righty Rollie Stiles’ wild pitch plunked him in the head. Rosar flirted with a .400 average throughout most of the year and his season-ending .387 led all Double-A hitters. In a surprise move, International League President Frank Shaughnessy declared Rosar the circuit’s batting champ despite a mere 323 at-bats (255 fewer than Keller, his teammate and closest competitor, who batted .365). Within days after the World Series the Yankees traded catcher Joe Glenn to the St. Louis Browns, clearing the path for Rosar’s expected promotion.

Perhaps no greater compliment was paid to Rosar than the one he received from St. Louis Cardinals boss Branch Rickey, who in February 1939 invited the young catcher to demonstrate his hitting techniques before a contingent of Cardinals prospects at a Rochester, New York, clinic. Two months later The Sporting News identified Rosar among Keller and Ted Williams as the group of first-year players “expected to set new standards for rookies”;4 a high barrier amid projections that the 24-year-old would do no more than split “double-headers with the best catcher in the business.”5 The latter forecast proved true when Rosar got a mere 11 at-bats through the first 69 games of the season. He made the most of his limited opportunities with two 4-for-4 games, against the Browns and Philadelphia Athletics on July 18 and August 20, respectively. The latter display coincided with Dickey’s August tumble – .212 in 119 plate appearances – as Rosar earned more playing time through the end of the season. He finished his rookie season with a .276/.356/.343 line in 105 at-bats.

In 1940 Rosar began receiving more play before another split hand on May 20 sidelined him for 25 games. On July 4 he collected his first two major-league home runs in consecutive at-bats while leading the Yankees to a 7-3 win over the Red Sox. (Both homers came off Emerson Dickman, the pitcher who was on the mound in Buffalo the day Rosar was discovered.) Two weeks later he connected on his next four-bagger, a bases-loaded blast off Cleveland lefty Al Milnar. The next day he hit for the cycle in a 15-6 rout of the Indians. He surged to a .347 batting average in September, including another 4-for-4 performance on September 28 against the Washington Senators. Though Rosar more than doubled his plate appearances from the preceding year, these offensive displays were still played out in the shadow of Dickey. This would remain so over the next two years as Dickey’s playing career wound down. On October 2, 1941, Rosar made his postseason debut as a defensive replacement in Game Two of the World Series.6 The following July he and Dickey were both on hand at New York’s Polo Grounds on the AL All-Star Game squad (though neither got into the game).

Rosar, batting .352 at the 1941 All-Star break, might easily have been chosen for the AL squad, but he had other plans; during the break Rosar married Ruth Therese Boyle in Buffalo.7 Ruth was a sports enthusiast and, as one of the best women bowlers in Buffalo, shared a love of tenpins with her husband. They had four children, and the birth of Warren Jr. on July 20, 1942, contributed to the personal drama that quickly surrounded Rosar. After the July 18 home win against the Chicago White Sox, Rosar bolted the Yankees without permission to take the police entrance exam and be present for the expected birth of his son. Manager McCarthy may have shown more leniency toward the new father had Bill Dickey not been nursing an injury. On July 19, in a hasty acquisition, the Yankees signed Rollie Hemsley two days after the veteran catcher had been released by the Cincinnati Reds. Angered by Rosar’s absence, team president Ed Barrow threatened to trade him. He settled on a $1,000 fine that McCarthy, even no less angered, talked down to $250. But the situation was far from forgotten. On December 17, shortly after the Red Sox expressed interest in Rosar, the catcher was traded to the Indians with utility outfielder Roy Cullenbine for center fielder Roy Weatherly and infielder Oscar Grimes (excepting Grimes, the swap consisted of players who had each worn out his welcome in his 1942 locale).

Initially angered by the sendoff, Dickey’s heir-apparent threatened to retire before realizing the opportunity before him. “[I’ve] got a big break,” Rosar said. “If I had caught 100 games a year for the Yankees, in the eyes of the public I’d still have been a second-string catcher. … That’s how high Bill Dickey stands – and rightly so. With the Indians I hope to be a regular.”8 Those hopes were realized when Rosar wrestled the starting job from incumbent Gene Desautels. After flirting with a .300 average through June 27, 1943, Rosar got a second consecutive All-Star Game berth and finished the season with a .283/.340/.340 line with one homer and 41 RBIs in 382 at-bats.

During the offseason Rosar worked at a war materiel factory in Buffalo, a position he refused to vacate in the spring of 1944. The Indians, with Commissioner Kenesaw Landis’s blessing, arranged a similar job for Rosar in Cleveland. He worked at a local plant during the day and joined the club at night and on weekends both home and away; Rosar’s teammate Ray Mack was provided an identical provision. (The Indians’ arrangements were not isolated cases during World War II; the Browns did the same for outfielder Chet Laabs.) Excluding a late slump (likely attributable to exhaustion), Rosar proved productive for the second-division club throughout the entire season; including a 5-for-6 performance against the Browns on June 11 that contributed to a 13-1 Indians win. Though Rosar scheduled his vacation days to accompany the Indians on several road trips, player-manager Lou Boudreau was still not pleased with the part-time arrangement. When the season ended, reports immediately surfaced of Rosar’s pending departure despite his league-leading .989 fielding percentage among catchers.

The winter of 1944-45 played out nearly the same way. Amid rumors of a trade to the Browns, Rosar returned to the Buffalo factory, again threatened to retire from baseball. (A salary dispute appears to have contributed to the impasse.) For the second consecutive year Rosar refused to report to spring training as the Indians dangled him before other clubs. With Dickey serving in the US Navy, a deal was nearly made with the Yankees before Rosar was traded to the Philadelphia Athletics on May 29, 1945, for catcher Frankie Hayes. The rust from the long layoff was readily apparent as Rosar struggled to keep his average above .200 through much of the season (though he was able to elevate his game with a 6-for-11 surge and four RBIs against his former Indians teammates in a July three-game series). On September 9 Rosar’s veteran presence behind the plate helped 24-year-old Dick Fowler as the righty tossed the Athletics’ first no-hitter in 29 years; it was the first of two career no-hitters Rosar caught.9 Five days later, in a rain-shortened game against the Detroit, Rosar was charged with an error after missing a tag of Tigers baserunner Bob Maier. Arguing that Maier had run out of the baseline, Rosar was thrown out of the game after bumping the umpire.10 The error was his first in 25 games and proved to be his last over the next 147 record-setting games. When the season ended the war was over and the defense job was no longer an option for Rosar. Joining a barnstorming club made up of AL All Stars, the team was shaken on October 9 when their train derailed 10 miles north of Great Falls, Montana. The accident killed the train’s engineer and fireman. The players were unnerved but escaped injury.

In 1946 Rosar reported to spring training for the first time in three years. His strong Grapefruit League campaign contributed to an equally strong year as Rosar became one of the “consistent bright light[s] in the debacle”11 that was the Athletics’ 105-loss season. He placed among the team leaders with a .283 average and had career highs in hits (120), doubles (22), and RBIs (47). Rosar became the first major-league catcher to go an entire season without a miscue (100 or more games) and had a season-record 605 errorless chances. For the first of two consecutive seasons he led the league in caught stealing and assists by a catcher. The only downside to his season was the 20 double plays he grounded into, trailing only center-field teammate Sam Chapman (22) for the major-league lead (a further indictment of the feeble Athletics). For the first of three consecutive years, and the first time in his career, Rosar played in the All Star Game. And for the first of two straight years he earned a smattering of consideration for the AL Most Valuable Player award. The Yankees’ new president, Larry MacPhail, aggressively pursued Rosar after the season, first in a proposed multi-player swap, then by a three-team deal (the Red Sox were the third team) in which the catcher would return to the Pinstripe fold. MacPhail’s efforts continued into June 1947, long after Philadelphia had signed Rosar to a two-year extension with a sizable raise. “[With] his handling of pitchers and his throwing … [Rosar] is the best maskman in the majors,” Athletics owner Connie Mack said after the contract was signed.12

But in 1947 injuries began to overtake the aging catcher. Despite two more All-Star selections, Rosar played fewer games in each year through 1950 (a mere 27 in the latter season). The reasons for lost time ranged from torn cartilage to influenza, and in one instance he was sidelined with an eye infection that prevented him from focusing properly. On October 8, 1949, Rosar was traded to the Red Sox for infielder Billy Hitchcock, and was happily reunited with skipper Joe McCarthy. (More than once the manager had expressed regret over the 1942 parting of Rosar.) But the reunion was short-lived; McCarthy, citing ill health, resigned on June 22, 1950. Rosar’s healthy return coincided closely with McCarthy’s parting and the catcher received most of his play – limited as it was – under new manager Steve O’Neill.

Throughout the 1951season O’Neill used no fewer than seven catchers, with newly acquired Les Moss and a relatively healthy Rosar earning the bulk of the backstop duties. (Rosar missed more than two weeks with a broken hand.) Shortly after his 37th birthday, glimpses of Rosar’s former capabilities were spied: On August 2 he collected two hits and three RBIs in leading the Red Sox to a 12-1 win over the Browns; six weeks later he went 3-for-3 with two runs, a home run, and three RBIs in a 5-4 win over the White Sox. On September 19 Rosar started against the Indians in a lopsided 15-2 loss; it proved to be his last appearance in the major leagues. Within days after the season ended, the Red Sox hired Lou Boudreau to replace O’Neill. The first player transaction under the future Hall of Famer was the release of Rosar.

The veteran catcher returned to the hamlet of Eggertsville, New York, his home outside Buffalo. Despite his age, Rosar was not ready to retire; the following spring he worked out with the Buffalo Bisons hoping to attract major-league interest. He was also very vocal about his desire to coach or manage. After the 1958 season the Bisons reportedly considered hiring Rosar to replace manager Phil Cavarretta before settling on Kerby Farrell. After holding down a variety of offseason occupations –factory worker, dairy-truck driver and, in the 1940s, a New York Central Railroad policeman – Rosar went to work as an engineer at the Ford Motor Company plant in Buffalo.

Both during and after his playing career Rosar had forged close ties to his native Buffalo. In 1949 he joined fellow major leaguers Stan Rojek and Sibby Sisti in launching a series of six baseball clinics on behalf of Father Baker’s Orphanage in nearby Lackawanna, New York. He played and coached basketball and there is some evidence that in the 1930s he played professionally in the American Basketball League (one of the predecessors to the NBA) before the Yankees demanded a halt. His son Warren Vincent “Buddy” Rosar Jr. became an accomplished third baseman at Canisius High School before moving behind the plate for four seasons with the State University of New York Maritime College.

Throughout his career Rosar used a very small catcher’s mitt. In 1960 the National Baseball Hall of Fame received his glove to commemorate both the longest tie game in AL history, played on July 21, 1945 (in which Rosar caught the entire 24 innings), and the Fowler no-hitter two months later. In 1963 Rosar was in Cleveland Stadium to commemorate the 1948 world champion Indians in an Old Timer’s exhibition.

On March 13, 1994, four months removed from his 80th birthday, Rosar died in Rochester, New York. He was buried in Mount Calvary Cemetery in Cheektowaga, New York. He was survived by two sons, two daughters, 11 grandchildren, and one great-grandchild. In 2010 Rosar was inducted into the Greater Buffalo Sports Hall of Fame.

Rosar’s major-league career spanned 13 seasons during which he accumulated a .261/.330/.334 line with 18 home runs and 367 RBIs in 3,198 at-bats. A highly prized prospect, Rosar spent four of his most productive years sitting behind Bill Dickey. A brilliant defensive catcher, he holds the 20th-century mark for the fewest passed balls per games caught (0.0300) with only 28 such miscues in 934 games. His frequently stated desire to remain in baseball after he retired was likely blocked by teams wary of the number of times Rosar held out, threatened to retire, or bolted from his teammates altogether in 1942.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Len Levin for review and editing of the narrative.

Sources

Besides the sources listed in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-reference.com and Ancestry.com.

Notes

1 “Minors Worth Watching,” The Sporting News, August 15, 1935: 2.

2 Rosar was known as a voracious eater; unlike Steve Sundra, his future Yankees teammate who could eat continually without gaining an ounce, Rosar did not share that luxury.

3 Bill Weiss and Marshall Wright, “Top 100 Teams: 1937 Newark Bears,” Accessed March 9, 2016, milb.com/milb/history/top100.jsp?idx=3.

4 “Younger Generation Coming Up,” The Sporting News, April 27, 1939: 4.

5 “Giants’ Suffering May Cause Terry to Begin Surgery,” The Sporting News, August 31, 1939: 2.

6 A year later Rosar made his second (and final) postseason appearance, delivering a pinch-hit single in Game Four of the 1942 World Series.

7 In January 1939 Rosar was reportedly engaged to Rochester, New York, native Florence J. Ott; no reason was ever given regarding this split.

8 “Rosar’s Light No Longer Hidden,” The Sporting News, March 25, 1943: 8.

9 A third no-hitter was lost on August 26, 1947, when Indians pinch-hitter George Metkovich lined a ninth-inning, one-out single to center field. Rosar would be fined $25 after arguing an eighth-inning walk that ended pitcher Phil Marchildon’s bid for a perfect game.

10 Rosar’s reputation as an ump-baiter contributed to a volatile relationship with the men in blue throughout his career.

11 “’Flogging Five’ of Phillies Keeping Flingers Aflutter,” The Sporting News, August 7, 1946: 8.

12 In 1948, in an ironic twist, A’s pitchers complained that Rosar called for too many curveballs.

Full Name

Warren Vincent Rosar

Born

July 3, 1914 at Buffalo, NY (USA)

Died

March 13, 1994 at Rochester, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.