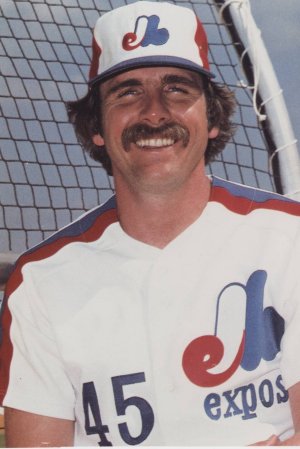

Steve Rogers

For many people, Steve Rogers is the guy who gave up the game-winning home run to Rick Monday in the 1981 National League Championship Series. However, to think of him for just that one pitch does a disservice to a player who was a five-time All-Star, an ERA leader, and the ace of the excellent Montreal Expos teams of the late 1970s and early 1980s.

For many people, Steve Rogers is the guy who gave up the game-winning home run to Rick Monday in the 1981 National League Championship Series. However, to think of him for just that one pitch does a disservice to a player who was a five-time All-Star, an ERA leader, and the ace of the excellent Montreal Expos teams of the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Stephen Douglas Rogers, the eldest of six children, was born in Jefferson City, Missouri, the state capital, on October 26, 1949, to Doug and Connie Rogers. His father was a dentist. His parents had specific plans for having a family but ended up having three children by the time they intended to have one. “Planning wasn’t their forte, let’s put it that way,” Rogers said.1

Rogers made his high-school baseball team as a junior but pitched in only two games that year. He made the squad again as a senior and pitched the team to the semi-finals of the state high-school championship tournament, where he lost 2-0 to future major leaguer Jerry Reuss.

That section of Missouri was a hotbed of baseball talent and Rogers was scouted by the Yankees’ Tom Greenwade, who signed Mickey Mantle. The Yankees drafted Rogers in the 67th round of the 1967 draft, but Rogers’ father, who knew Greenwade, told him that Rogers wasn’t ready yet.

“Rookie ball would have chewed me up and spit me out,” Rogers said.

Greenwade, realizing Rogers’ potential, recommended him to Gene Shell, the baseball coach at the University of Tulsa. He told Shell that Rogers was young and raw but would one day pitch in the majors. Coach Shell scouted Rogers in an American Legion game that summer. He had a bad game that day, and years later Shell told him that he had called Greenwade and asked him if he was sure about his assessment of Rogers.

Despite Shell‘s misgivings, Rogers attended the University of Tulsa in the fall of 1967 and embarked on a fine university baseball and academic career.

Rogers’ University of Tulsa team was very talented. They made it to the championship game of the College World Series in his sophomore season, 1969, assisted, no doubt by a bigger, stronger Rogers (he grew three inches in the summer after his freshman year). In his senior year, 1971, they not only made it to the tournament semi-finals, but Rogers received an All-American selection.

Rogers graduated with a degree in petroleum engineering and enough talent to be drafted fourth overall by the Expos in the secondary phase of the 1971 amateur draft. The Expos sent him to their Triple-A farm team, the Winnipeg Whips of the International League.

It would have been more appropriate to call this team the Winnipeg Whipped because of their 44-96 record, 42 games out of first place (and 16 games out of seventh) in an eight-team league. Rogers had a 3-10 record, although with a respectable 3.97 ERA. He was disappointed that the Expos sent him to the minors; he thought he was ready for “The Show.” Rogers’ assessment of his readiness for the majors received a reality check from the powerhouse Rochester Red Wings, who had future major-league stars Don Baylor, Al Bumbry, and Bobby Grich in their lineup and gave him his lumps each of the three times he pitched to them.

“They pinned my ears back and said, ‘Son, you got a ways to go,’ ” Rogers said.

In 1972 the Whips moved to the Tidewater area of Virginia and were renamed the Peninsula Whips. Although they still ended up at the bottom of the pack, their record improved to 56-88. Rogers was only 2-6 that year and his ERA rose to 4.08. He began the 1973 season with the Whips and was 3-1 with a 1.86 ERA when the Expos called him up in mid-July.

The pitcher’s career with the Expos got off to a bit of a rocky start thanks to a cranky Canadian customs agent. When Rogers drove up to the Canadian border, the customs agent knew who he was, but told him he needed to produce his signed contract or he couldn’t enter the country. Not surprisingly, Rogers didn’t have any documents from the Expos, so he was forced to return to the United States.

Enter an American customs agent who was understandably curious about why Rogers was returning to the US. When Rogers explained his situation, the helpful agent told him about another, smaller border crossing down the road that he could try. Rogers drove to the other location only to find another ever-diligent Canadian customs person who called the original crossing, came back and gave Rogers an earful. Rogers had to spend the night in Plattsburgh, New York, 60 miles from Montreal. He was able to enter the country the next day. What followed was one of the most remarkable rookie seasons in baseball history.

In his first start, against the Houston Astros in the Astrodome on July 18, Rogers went eight innings, gave up two runs on four hits, but got a no-decision in a game the Expos won 3-2 in ten innings. Eight days later he got his first major-league win in style, pitching a 4-0 one-hitter against Steve Carlton and the Philadelphia Phillies at Veterans Stadium in Philadelphia.

That first win wasn’t the most memorable one for Rogers. That came in his next game, against the New York Mets at Shea Stadium in New York. Rogers held the Mets scoreless and the Expos got a run in the top of the ninth to give him a 1-0 victory. Rogers ended up with a 10-5 record that season, seven complete games, three shutouts and a 1.54 ERA. He came in second to the San Francisco Giants’ Gary Matthews in Rookie of the Year voting. Teammates Ron Fairly and Tim Foli bestowed the nickname Cy (as in Cy Young) on Rogers, and it stuck with him the rest of his career. “It was a fairy tale year,” Rogers said.

Rogers’ first season may have been out of Mother Goose, but his next three seasons read like something written by the Brothers Grimm. Despite bone chips in his elbow, Rogers had 38 starts, 37 decisions, and a 15-22 record with a 4.47 ERA for the middle-of-the-pack Expos in 1974. Rogers started off well and was 6-1 in May when things started going wrong. He lost his confidence after getting knocked out of a game on May 18 against the Mets in which he gave up six runs in three innings. Add to that the fact that other teams were now familiar with him, he had arm trouble, and perhaps suffered from a dash of sophomore jinx, and you have an explanation for his record.2 Rogers made 38 starts that season; his only no-decision came on July 17 in a game in Los Angeles in which Tommy John suffered the injury that resulted in the surgery that bears his name.

Maybe Yogi Berra, the National League manager in the All-Star Game, had some insight into Rogers’ physical problems because he chose him to represent the Expos at the All-Star Game. Rogers didn’t get a chance to play.

No-decisions were a way of life for Rogers in 1975 as he had 13 of them while struggling to an 11-12 record. But he took more than one run off his ERA, bringing it down to a respectable 3.29.

America’s Bicentennial year, 1976, was a disaster for Canada’s baseball team. The Expos were a young, raw, overmatched team that year, losing 107 games. Rogers contributed 17 of those losses, combined with seven wins. It was a tough year for Rogers physically, as he broke his hand hitting a bat rack and later developed tendinitis. Still, his ERA that season dropped even further, to 3.21.

The Expos moved from cozy little Jarry Park to the massive Olympic Stadium in 1977, and perhaps the change in atmosphere accounted for the upswing in Rogers’ career. His record was over .500 for the first time since his rookie year (17-16) and he lowered his ERA yet again, to 3.10. The improvement continued in 1978. Rogers went 13-10 with a 2.47 ERA even though the team averaged less than three runs per game in his first 22 starts. He received his second All-Star Game selection. He pitched two innings in the classic, gave up two hits but didn’t allow any runs and struck out sluggers Jim Rice and Richie Zisk back-to-back.

Rogers also got into a fistfight with general manager Charlie Fox that season. Fox, an old-school Irishman, was haranguing Expos shortstop Chris Speier because he felt that Speier’s play wasn’t up to snuff. The volume of the discussion was steadily increasing when Rogers, the team’s player representative, intervened. Rogers and Fox got into an argument. Fox then brought things to a head. More specifically, he brought things to Rogers’ head in the form of a punch to the jaw.3

Rogers told journalists, “I don’t know if I intervened because I was the player representative or simply as a teammate assisting in a disgraceful situation.” 4

That incident had some interesting ramifications. Speier went out that night, hit for the cycle, and drove in six runs. But team morale suffered and the Expos went on to lose seven in a row, while Fox was shown the door. Rogers’ season ended in August of that year when he had surgery by Dr. Frank Jobe for elbow tendinitis.

The 1979 season was pivotal for the Expos as a talented young team blossomed into a powerhouse, winning 95 games and fighting the Pittsburgh Pirates for the division title right up to the last weekend of the season. Rogers had a 13-12 record, a 3.00 ERA, and his second consecutive All-Star appearance (two three-up-three-down innings with two strikeouts). He led the league in shutouts with five. However, there’s more to the story of this season than numbers. The Expos’ manager that season was Dick Williams, who could never be mistaken for a players’ manager. He wanted results and wasn’t too interested in what players thought of his methods. Williams and Rogers hated each other, and Williams wasn’t afraid to voice his opinion about Rogers’ play.

In a July 12 game against the Giants, for example, Rogers was at the plate with a 3-0 count and for some reason began to swing at the fourth pitch of the at-bat. He tried to check his swing but connected. He managed to get a hit out of it but was picked off first base. Williams was furious, especially when Rogers said he missed the “take” sign. Williams said, “In a play like that, there’s no signal; you don’t swing and that’s final. Even Babe Ruth would watch the ball go by.”5

In his autobiography, aptly titled No More Mr. Nice Guy, Williams said it was “one of the stupidest and most egotistical plays” he had ever seen in a baseball game.6 Rogers, for his part, said he screwed up and it was entirely his fault.

The two-part video series Les Expos Nos Amours, hosted by Donald Sutherland, laid bare the Rogers-Williams feud. In it, Williams said, “Steve Rogers was a total disappointment as far as I was concerned. If you needed a big game he could never give you that total effort. He never did.”7

Rogers’ assessment of the relationship was blunt: “We got along like fire and water,” he said. As for his opinion of Williams being named Manager of the Year in 1979, Rogers said, “If he was given Manager of the Year, it would be the first time a positive reward was given for a negative influence.”8

The extent of the pressure that Williams placed on Rogers was evident just before a critical September 26 start against the eventual world champion Pirates in Pittsburgh. As Rogers prepared for the game, a reporter asked him what he thought of Williams’ comment that he would have liked to use one of his good pitchers like Bill Lee or David Palmer, but that he had to go with Rogers.9 Perhaps not surprisingly, Rogers gave up three runs in four innings that night as the Expos lost 10-1. The next day, a Montreal reporter wrote, “Rogers, supposedly the ace of the staff, is no more or no less than a constant loser.”10

It seemed that even his fellow pitchers on the team found it easy to be critical of Rogers that season. Bill Lee said he was too much of a perfectionist.11 Also, as Doucet wrote, Ross Grimsley thought Rogers treated every pitch as if it were a matter of life and death, and mannerisms he displayed on the mound (sighs, deep breaths, grimaces), “got on the nerves of some teammates who saw them as signs of discouragement.”12

The 1980 season allowed Rogers to show what he was truly made of after the pressure and criticism he endured in 1979. Long the subject of trade rumors, he was able to breathe more easily after a trade to the Texas Rangers for outfielder Al Oliver was quashed when Oliver exercised his no-trade clause. (Oliver eventually joined the Expos in 1982 in exchange for Larry Parrish.) Even the coolness between Rogers and Williams melted in the warmth of the Florida sun during spring training.13

The results were predictable: a 16-11 record with a 2.98 ERA and a league-leading 14 complete games. Any doubts about Rogers’ abilities in the clutch were laid to rest as he led the Expos to a 92-70 record. Montreal was eliminated on the next-to-last day of the season despite Rogers’ efforts down the stretch. From August 25 to the end of the season, he was 4-2 with two shutouts and five complete games. This included a complete-game 8-3 victory over Steve Carlton and the Phillies in Philadelphia on September 28 that gave the Expos a brief half-game lead. The Expos were shut out in both the losses, including a 2-0 déjà vu defeat at the hands of Jerry Reuss, his nemesis back in his high-school days.

The next season, 1981, was the only one in which the Expos made the playoffs. Being remembered solely for the home run he gave up to Rick Monday doesn’t do justice to the fact that it was Rogers’ pitching that got the Expos so close to the World Series in the first place.

After a players strike in the middle of the year, the major-league season was split in two, with the winners of each half facing each other for the right to advance to the League Championship Series. In the National League East, the Expos, winners in the second half, squared off against the first-half champion Phillies in a best-of five series that the Expos won three games to two. Rogers went 8 1/3 innings in Game One as the Expos beat Steve Carlton 3-1. A second Rogers-Carlton showdown in Game Five was no contest; Rogers not only won a 3-0 complete-game victory, but drove in two runs with a single.

Game Three of the National League Championship Series against the Los Angeles Dodgers brought Rogers a modicum of revenge against Reuss, as he pitched another complete game in a 4-1 Expos win. Then came Game Five, in which he entered the game in the ninth inning, and the pitch to Monday.

Rogers also played a big role off the field that season; he was one of four players directly involved in the negotiations with the major-league owners during the strike, along with Bob Boone, Doug De Cinces, and Phil Garner.

Rogers also played a big role off the field that season; he was one of four players directly involved in the negotiations with the major-league owners during the strike, along with Bob Boone, Doug De Cinces, and Phil Garner.

If giving up the fateful home run to Rick Monday was disappointing to Rogers, he certainly got over it in time for the 1982 season, arguably the best of his career. He was 19-8, led the league with a 2.40 ERA, and finished second in the voting for the Cy Young Award. He started and won the All-Star Game, the only time it was played in Montreal.

Rogers was an All-Star again in 1983 as he finished with a 17-12 record and a 3.23 ERA and again led the league in shutouts, with five. He finished fourth in the Cy Young voting and was selected for the All-Star Game. (He didn’t pitch in the game, in which the American League hammered the National League 13-3.) As well as he pitched, the 1983 season was Rogers’ last effective campaign as a major-league pitcher. All those innings finally caught up with him in 1984 as an injured shoulder made it impossible to pitch effectively and he ended with a 6-15 record. He was released by the Expos in May 1985, season, and after a few minor-league starts for the California Angels and Chicago White Sox, he retired at the end of the season.

Rogers moved back to Tulsa and started an oil company with three partners at a time when oil was $24 a barrel. The price of oil soon fell to $10 a barrel, which marked the end of that venture. Rogers tried selling real estate, but that proved a tough task in oil-dependent Tulsa. Then the players union came calling. Rogers’ years as a team representative and negotiator worked to his advantage in 1987 when the Major League Baseball Players Association asked him to serve as an outside consultant on pension issues. The following year he began writing reports relating to collusion cases. He began working for the players association full time in 1999 and as of 2012 he was a special assistant to association Executive Director Michael Weiner, carrying out administrative duties, reconciling dues, and keeping up with the benefit plan among other responsibilities. He and his wife, Robin, resided in New Jersey; their daughter, Jennifer, 21, was a student at the University of Oklahoma. His two sons from his first marriage, Jason and Geoffrey, run car dealerships in Oklahoma. He has two grandchildren.

Rogers showed a reflective side when he was asked by an interviewer for the video Les Expos Nos Amours if there was one piece of his career that he could change. He did not say it was the Rick Monday pitch. Instead, he said: “The last five years of my career I felt the most confident and could contribute on a regular basis, and it was all because I learned that if I established a good work ethic I could hold my head up after every game and know that I worked as hard as I possibly could to make that a winning start, and I don’t know I did that often enough my first four or five years. If I could change anything it would be that.”14

Rogers retained ties to Montreal and Canada. He and former Toronto Blue Jays pitcher Dave Stieb were elected to the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame in 2005. He said he was also proud of the role he played in establishing the Expos’ identity. “The Montreal Expos emblem was an oddity in 1973 in the National League,” said Rogers. “The Montreal Expos emblem in 1985 was an established major-league emblem of a solid organization and to have been part of that is a very special part of my life.”15

Sources

Jacques Doucet and Marc Robitaille, Il etait une fois les Expos, Volume 1, 1969-1984 (Montreal: Editions Hurtubise, 2009).

Rick Hummel, “Unknown Expos Dangerous When Cornered,”The Sporting News, October 11, 1980.

http://www.baseball-reference.com/

http://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/1969_College_World_Series

http://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/1971_College_World_Series

http://kevinglew.wordpress.com/2011/07/13/1981-montreal-expos-whatever-happened-to-steve-rogers/

Interview with Steve Rogers, April 9, 2012.

Notes

1Unless otherwise noted, all quotes by Rogers are from an interview conducted on April 9, 2012.

2 Jacques Doucet and Marc Robitaille, Il etait une fois les Expos” Volume 1, 1969-1984 (Montreal: Editions Hurtubise, 2009), 208.

3 Doucet and Robitaille, 332.

4 Doucet and Robitaille, 333.

5 Doucet and Robitaille, 371.

6 Doucet and Robitaille, 371.

7 Video: Les Expos Nos Amours, Volume 2, Labatt Productions, 1989.

8 Les Expos Nos Amours.

9 Les Expos Nos Amours.

10 Doucet and Robitaille, 391.

11 Doucet and Robitaille, 390.

12 Doucet and Robitaille, 391.

13 Doucet and Robitaille, 400.

14 Les Expos Nos Amours.

15 Les Expos Nos Amours.

Full Name

Stephen Douglas Rogers

Born

October 26, 1949 at Jefferson City, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.