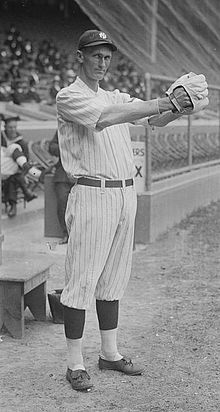

Slim Love

“A pitcher can make great use of his tallness when he is as big as me, because when he gets on the hill he can zip ’em through there so fast it’s like tryin’ to hit a ball thrown off the top of the Washington Monument, and you have got a fine chance of hitting a ball thrown off of that building.”

“A pitcher can make great use of his tallness when he is as big as me, because when he gets on the hill he can zip ’em through there so fast it’s like tryin’ to hit a ball thrown off the top of the Washington Monument, and you have got a fine chance of hitting a ball thrown off of that building.”

Slim Love said that of the benefits of being the tallest hurler in the big leagues.1 Using his extraordinary height to his advantage, Love — once called the “greenest man that ever broke into baseball” — experienced an improbably rapid rise from rural semipro ball to the major leagues.2 Despite his size and potential, however, the “tall pine” never attained significant success on the mound during his relatively brief big-league career.3

Edward Haughton Love was born on August 1, 1890, in Love, Mississippi, a small community in the northern part of the state about 30 miles south of Memphis, Tennessee. Love contended in an interview that the town was named after his farmer grandfather; however, contradictory county genealogical research indicates that its eponymous founder was actually a physician prominent in the early days of the area.4 Love’s father, Columbus, was a farmer, and his mother, Mary, was a home maker. The couple had four other children: John, Columbus, Julia, and Emily. Love was the second youngest.

Tall genes apparently ran in the family, as his father and mother were reportedly 6-foot-6 and 6-foot-3, respectively.5 Edward eventually grew to 6-foot-7. His relatively slight 195-pound frame perhaps unsurprisingly gave rise to the nickname “Slim,” which became synonymous with the lanky southpaw. Curiously, he was tagged in the press with the nickname “Reno” in his first season of professional ball. The origin of this moniker is unknown, and seemingly quickly disappeared from usage as Love (and his new nickname) grew in fame in 1913.

While a youngster, Love learned to throw a curveball playing on amateur teams. From this humble beginning, he later attained a position on the pitching staff of the local semipro ball club while still spending most of his time working on his father’s farm. Despite displaying considerable skill on the mound, Love’s future plans had nonetheless revolved around eventually finding employment at a local railroad. Those plans were shelved, however, when he was offered a trial with the Memphis Chickasaws of the Class-A Southern Association. Differing accounts exist as to how Love progressed from being a small-town semipro player to securing a tryout with an upper-level minor-league team. In one version, the aspiring hurler obtains the tryout through help from a railroad engineer pal who had connections to Chickasaws manager Bill Bernhard.6 Another perhaps more amusing account has the bucolic Love securing the tryout after boldly convincing big-city diners at a popular Memphis café — including its proprietor who reportedly had connections to Bernhard — that he was “one of the best pitchers in the world” and had “come up from Mississippi to pitch Memphis to a pennant.”7 In either case, what can be confirmed is that the 21-year-old did indeed get a trial run with Memphis in the spring of 1912.

Love flashed potential for the Chickasaws, most notably striking out future Hall of Famer Nap Lajoie with the bases loaded during an exhibition game against the American League’s Cleveland Naps.8 Although he featured a fastball that could “kill an ox,” the southpaw struggled with fundamentals, including the ability to field his position.9 “It was ludicrous to see him handling a bunt, and his delivery was so deliberate that the base runners would be halfway to second base before Slim could deliver the ball,” wrote the Winnipeg Tribune.10 Deciding the promising Love needed more seasoning, Bernhard sent the inexperienced hurler to the Greenwood Scouts of the Class-D Cotton States League to begin the regular season.11 Love struggled in Greenwood, however, and was released within a month’s time.12 He finished the season tossing for the Cairo Egyptians of the Class-D Kentucky-Illinois-Tennessee League.13

Following his disappointing inaugural campaign at the lowest level of Organized Baseball, Love’s fortunes changed dramatically in 1913. Although he began the season with the Selma Centralites back in the Cotton States League, the hurler’s performance, which included a 37-consecutive-inning scoreless streak and a no-hitter, gained him both confidence and a promotion to the Atlanta Crackers of the Class-A Southern Association in late July.14 Love immediately “pitched good ball” for the Crackers.15 So good that within a couple weeks of arriving in Atlanta, the “very promising young southpaw” was claimed by the AL’s Washington Senators at the behest of the club’s manager, Clark Griffith.16 Making his big-league debut on September 8 in a 4–0 loss to the New York Yankees, Love looked sharp in setting down the side in order in his only inning of work. “Though fresh from the tobacco and rice fields of Dixieland, Love didn’t worry a bit on being sent to the mound,” wrote the Washington Times. “He was perfectly cool and went about his business much as if he were a veteran.”17 At the time he was the tallest player to ever appear in the big leagues; no one taller arrived until 19 years after Love’s final major-league appearance.

On September 19, Love made his first major-league start and picked up his first victory, against Ty Cobb and the Detroit Tigers. Appearing in five games for Washington, Love finished his brief rookie season with a fine 1.62 ERA. His rapid ascent from struggling with fundamentals in Class-D ball to impressing in the big leagues was marveled at by the press. “Although far from being a finished twirler, his improvement in one season has been remarkable,” wrote the Winnipeg Tribune. “He can field a bunt without falling down, and has developed a fair move to first base.”18 Griffith also showered Love with praise: “He has the makings of a great pitcher, despite the fact that two years ago he was considered almost as much of a clown as was Charley Faust,” opined the Old Fox. “He has worked out most of that pitiful awkwardness, has a world of speed, has excellent control for such a comparatively green hand, and is willing to learn.”19

With Love’s fame on the rise, newspapers of the day often delighted in emphasizing the rural farm boy’s poor education and the fish-out-of-water situations in which he was increasingly finding himself. “And simple, say, the well-known Simon of nursery rhyme renown was an intellectual giant compared to Slim [Love],” wrote the New Castle (Pennsylvania) Herald.20 Another tale had Love, who as an amateur purportedly had played the game barefooted, astonished and bewildered at his first sight of spiked baseball shoes during his 1912 tryout with Memphis.21 And while with the Senators on a road trip to New York City, it was reported that the rookie pitcher was “so fascinated with the tall buildings and glare of the electric lights that he nearly missed his supper.”22

Despite his surprising debut in 1913, Love’s subpar curveball coupled with a strained ligament in his pitching arm resulted in a demotion back to the minor leagues.23 Spending the 1914 and ’15 seasons with the Los Angeles Angels of the Class-AA Pacific Coast League, the “human bean pole” was among the circuit’s best hurlers.24 After finishing a fine first season for the Angels in 1914, Love notably honed his skills in the first of his five sporadic off seasons spent in the California Winter League, the first integrated league in the United States in the twentieth century.25 Remaining with Los Angeles for the 1915 campaign after a contentious contract negotiation, Love passed on an opportunity to jump to the outlaw Federal League.26 Following his 23-win season for the Angels in 1915, however, the “human lightning rod” did not pass on joining the New York Yankees after he was drafted by the club in late September.27 Sportswriter Harry A. Williams summarized Love’s time on the West Coast: “Experienced players, men with major league experience, tell me that Slim is one of the toughest birds in the business to score on when he is feeling good. The very awkwardness of his delivery is an asset, tending to promote uneasiness on the part of the batter.”28

The 25-year-old Love impressed New York early on with the velocity of his fastball.29 However, troubles foreshadowing a difficult 1916 season began in late March when a freak injury involving tripping over railroad tracks left him on crutches.30 Quickly returning to action, Love got off to a rocky start when he was hit hard in his first regular-season appearance. In June he battled a bout of malaria.31 Although it was speculated during the course of the year that Love was a candidate for a demotion back to the minor leagues due to his wildness and lackluster performance, he managed to hang on with the Yankees for the entire season.32 He finished the disappointing year with a 2–0 record and team-worst 4.91 ERA in 20 appearances — all but one out of the bullpen.

But the Yankees’ coaching staff was not ready to give up on the lanky left-hander.33 “If that big fellow ever acquires control he will be as difficult to hit as Rube Waddell was in his best days,” opined manager Bill Donovan. “No left-hander since Rube’s time had such a good fastball. His curves break fast and his great height will add to his effectiveness.”34 Indeed, with dramatic improvements in his walk rate (and other pitching metrics) as the 1917 season progressed, Love found himself playing an integral role in the Yankees’ bullpen and as a spot starter. On the mound, the reported spitballer used a “cross-fire” delivery, described by sportswriter Norman E. Brown: “His ‘cross-fire’ — which seemed to come to a right-handed batter by way of first base and shoot straight at the batter’s head, was a baffling delivery. To a left-hander it seemed to sweep away in a wide arc that literally pulled the batter off his feet as he lunged for it.”35 Now considered as “one of the best of the Yankee pitchers,” during one stretch between mid-May and mid-June he tossed 39 1/3 consecutive innings without allowing an earned run.36 The highlight of Love’s season came during his May 30 start against the Philadelphia Athletics when he tossed an incredible 14 scoreless innings to pick up the victory. The World War I draft put his fine campaign at risk of a premature ending, but Love was rejected by Army examiners in August due to his weight being too light for his height.37 He finished his bounce-back year with a 6–5 record and 2.35 ERA in a team-high 33 appearances (including nine starts).

Picking up where he left off, Love continued as a “mainstay” of the Yankees’ pitching staff in 1918, this time as a member of the starting rotation.38 And he seemed to be acclimating to big city life. “Today Love is anything but a rube,” wrote sportswriter Joe Williams midway through the season. “Few players on New York’s crack team dress better than the tall left-hander. It is even reported that he carries a cane on Broadway.”39 By season’s end, Love posted a 13–12 record with a career-high 228 2/3 innings pitched in 38 appearances (including a team-high 29 starts). Despite his solid contributions of eating innings and bolstering the Yankees’ overall mound performance, the wildness had returned. Leading the AL in bases on balls, Love dubiously was among the league’s worst in walk rate and hit batsmen. Unsurprisingly, his ERA ballooned to 3.07, well above the league average. In December, the inconsistent hurler was traded along with Ray Caldwell, Frank Gilhooley, Roxy Walters, and $15,000 to the Boston Red Sox for Dutch Leonard, Duffy Lewis, and Ernie Shore. “Love is an erratic southpaw, who looks like a Rube Waddell one day and like a lemon another,” explained New York sportswriter W.J. Macbeth of the trade logic. “He may or may not develop into a star, but certain it is he could never be expected so to develop in local environment.”40 Less than a month later he was dealt again, this time to the Detroit Tigers, whose manager, Hughie Jennings, “wanted a southpaw pitcher badly.”41 In addition to Love, Boston sent Eddie Ainsmith and Chick Shorten to Detroit for Ossie Vitt.

“The contract offered me by the Detroit club calls for $100 less than I received when I first broke into major-league ball three years ago, and I have decided to quit,” Love reportedly proclaimed in February 1919.42 He subsequently disputed that report, and arrived a month later at spring training — albeit late — promising to work “his head off” for the Tigers.43 The “elongated, slender specimen” suffered a setback in late March, however, when he was shelved due to a fracture in his elbow.44 Although ailing, Love was able to make his first regular-season appearance in early May. The left-hander pitched reasonably well over the course of the season as a reliever and spot starter for Detroit, but was unable to crack the club’s veteran starting rotation.45 He posted a 6–4 record and 3.01 ERA in 22 appearances (including eight starts) on the year.

Back with the Tigers for the 1920 campaign, Love was shelled for four runs on six hits in 4 1/3 innings in relief in his first regular-season appearance on April 18 against Cleveland. Detroit manager Jennings released the 29-year-old the next day, not due to the singular poor performance versus the Indians, but rather because the “tall fellow” had “repeatedly broken training rules, both before the season started and since.”46 Love’s one and only 1920 appearance was his last in the major leagues, but he remained in the minor leagues for 11 seasons — winning well over 100 contests during that span. After leaving Detroit, Love returned to the Pacific Coast League for a few seasons where he split time between San Francisco and Vernon before settling down in the Class-A Texas League from 1922–1928. There he tossed for Beaumont, San Antonio, and Wichita Falls, but spent the lion’s share of his service with the Dallas Steers. In 1923 and ’24 he pitched in the integrated Cuban Winter League.47 The 1929 and ’30 seasons were tumultuous for the “altitudinous twirler,” as he bounced between Birmingham, Chattanooga, and Memphis in the Class-A Southern Association; Decatur in the Class-B Illinois-Indiana-Iowa League; and Baton Rouge in the Class-D Cotton States League prior to finally leaving Organized Baseball.48 Before hanging up his spikes, however, he toed the slab for independent clubs in Arkansas and Tennessee in the early 1930s.49

In his post-baseball years, Love settled down in Memphis with his wife, Mary, whom he met in Los Angeles during his initial stint in the Pacific Coast League.50 The couple married in 1916 and never had children. Into the late 1930s, Love was (presumably) self-employed as a pipefitter at the eponymously named Love Automatic Sprinkler Company.51 Around 1940, he entered the defense industry, working as a steamfitter at a naval base. In his free time, the “human telegraph pole” enjoyed hunting, fishing, and swimming.52

On November 30, 1942, while attempting to cross a Memphis street, Love accidentally walked into the side of a moving automobile and was tragically killed. He was laid to rest in Memphis. Love, for whom records indicate was Catholic, had remained locally active in sandlot baseball until his death.53

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Norman Macht for his review and edit of this biography, which was verified for accuracy by the BioProject fact-checking team.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author accessed Love’s file from the library of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York; Ancestry.com; Baseball-Reference.com; Chronicling America; GenealogyBank.com; NewspaperArchive.com; Newspapers.com; and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 James F. Taylor, “‘Slim’ Love, Tallest Man in Baseball,” Pittsburg Press, June 18, 1916: 62.

2 “Greenest Man Who Ever Broke into Game Is Hurling Great Ball for Boss Huggins,” Dayton Daily News, June 16, 1918: 8.

3 “Tallest Pitchers in Major Leagues,” Allentown (Pennsylvania) Democrat, September 30, 1913: 6.

4 “When Slim Love Met the New Baseball Boss,” Los Angeles Times, February 5, 1915: Part III, 1; “Cities/Towns,” Genealogical Society of DeSoto County, msgw.org/desoto/locality.html, accessed October 10, 2018.

5 “Baseball Dope,” Tampa Tribune, March 28, 1912: 4.

6 “When Slim Love Met the New Baseball Boss.”

7 “This Pitcher Talked Himself into Place,” Bridgeport (Connecticut) Evening Farmer, September 19, 1913: 9.

8 “Haste the Day When Reno Love Gets into Major League Baseball,” Buffalo Enquirer, July 26, 1913: 6.

9 Thomas S. Rice, “Gossip of the Superba Tourists,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 20, 1912: 2.

10 “Tallest Twirlers in Major Ball Leagues,” Winnipeg Tribune, October 11, 1913: 7.

11 “The Greenwood Team Being Strengthened,” Jackson (Mississippi) Daily News, April 22, 1912: 7.

12 “Orth Collins Crazy for a Good Catcher,” Vicksburg (Mississippi) Evening Post, May 2, 1912: 3.

13 “Vols Beat River Rats,” Clarksville (Tennessee) Leaf-Chronicle, June 7, 1912: 1.

14 Clyde Bruckman, “Introducing ‘Slim’ Love,” Los Angeles Times, April 28, 1914: Part III, 2.

15 “Smith and Love Are Sold to Senators,” Nashville Tennessean and the Nashville American, August 10, 1913: 9.

16 “‘Slim’ Love and ‘Wallop’ Smith Sold; John Voss and Elmer Lawrence Bought,” Atlanta Constitution, August 10, 1913: 9.

17 “Portside Flingers Look Pretty Good,” Washington Times, September 9, 1913: 10.

18 “Tallest Twirlers in Major Ball Leagues.”

19 “Griffith Boosts Love,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 7, 1913: 2.

20 “Slim Love Wins 1913 Rube Title,” New Castle (Pennsylvania) Herald, July 2, 1913: 9.

21 “The World of Sport,” Lincoln (Nebraska) Daily News, December 8, 1913: 8; Bruckman, “Introducing ‘Slim’ Love.”

22 Stanley T. Milliken, “To Book Three Exhibitions for Benefit of Nationals,” Washington Post, September 26, 1913: 8.

23 “Pitcher ‘Slim’ Love Joins Angels,” Oakland Tribune, January 4, 1914: 33; Bruckman, “Introducing ‘Slim’ Love.”

24 “This Pitcher Talked Himself into Place”; “Lush Hardest Pitcher in League for Opposing Batters to Nick for Tallies,” Oregon Daily Journal (Portland, Oregon), November 22, 1914: 4; “Lefty Williams Comes Close to Cack’s Marks,” Los Angeles Times, October 29, 1915: Part III, 4.

25 William McNeil, The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2002), 293.

26 “‘Slim’ Love Signs Name to Angel Contract,” Los Angeles Times, February 2, 1915: Part III, 3.

27 “Human Lightning Rod from Pacific Coast League Signs with Yankees,” undated newspaper clipping from Love’s file from the library of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; “Slim Love Signed by Yankees; Taken Away with Draft,” San Bernardino (California) News, November 1, 1915: 6.

28 Harry A. Williams, “Several Coast Clubs Must Rebuild in 1916,” Los Angeles Times, September 13, 1915: Part III, 3.

29 “Yankee Batters Impressed with Slim Love’s Speed,” Washington Times, March 6, 1916: 10.

30 “Slim Love Is on Crutches,” Los Angeles Times, March 20, 1916: Part III, 3.

31 “‘Slim’ Love Sick,” Washington Times, June 16, 1916: 14.

32 “Zeb Terry May Rejoin Angels,” Los Angeles Times, May 16, 1916: Part III, 1; “Diamond Sparks,” Courier-Journal (Louisville, Kentucky), November 26, 1916: 11.

33 “Baseball Gossip,” Pittsburg Press, March 20, 1917: 23.

34 “Slim Love New Sensation May Be a Second Waddell,” El Paso Herald, June 21, 1917: 9.

35 Gayle Talbot, Jr., “Sport Gossip,” Bryan (Texas) Daily Eagle, March 22, 1930: 3; Norman E. Brown, “Sports Done Brown,” Herald-Press (St. Joseph, Michigan), May 18, 1928: 12.

36 “Slim Love New Sensation May Be a Second Waddell.”

37 “Baseball Gossip,” Pittsburg Press, August 26, 1917: 19.

38 “Rule Reversed in Case of Slim Love,” Evening Public Ledger (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), May 10, 1918: 16.

39 Joe Williams, “‘He Who Laughs’ Fits Love’s Case,” St. Petersburg (Florida) Times, June 18, 1918: 3.

40 W.J. Macbeth, “Lewis, Leonard and Shore Come to New York Club,” New York Tribune, December 19, 1918: 15.

41 Harry Bullion, “Tigers Gain Strength by Trade that Sent Vitt to World Champion Red Sox,” Detroit Free Press, January 19, 1919: 15.

42 “Slim Love Given $100 Less Than 3 Seasons Back,” Oregon Daily Journal (Portland, Oregon), February 25, 1919: 14.

43 “Love Is Late but All Ready to Start Work,” Detroit Free Press, March 21, 1919: 13.

44 “Fractured Bone in Left Elbow Shown by X-ray of Love’s Arm,” Detroit Free Press, March 28, 1919: 13; Robert W. Maxwell, “Jinx Is Nibbling at Tigers Staff Hitting Slim Love,” Charlotte (North Carolina) News, April 9, 1919: 7.

45 Harry Bullion, “Young Signs with Tigers; So Does Love,” Detroit Free Press, January 14, 1920: 14.

46 Harry Bullion, “Tails from the Tigers’ Lair,” Detroit Free Press, April 20, 1920: 19.

47 Christopher Hauser, Negro Leagues Chronology: Events in Organized Black Baseball, 1920–1948 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2006), 20.

48 Jinx Tucker, “Sport Hotshots,” Waco (Texas) Tribune-Herald, June 16, 1929: 8; Ralph McGill, “Cullop’s Home Run Beats Lookouts, 5–4,” Atlanta Constitution, August 11, 1929: 15; “Johnny Berger Is Again Able to Rejoin Tribe,” Nashville Tennessean, May 15, 1930: 13; February 20, 1915, untitled newspaper clipping from Love’s file from the library of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

49 “Memphis Independents to Play at Osceola,” Blytheville (Arkansas) Courier News, April 11, 1931: 1; “Play Memphis Club,” Daily Clarion-Ledger (Jackson, Mississippi), July 27, 1932: 8.

50 “Diamond Dust,” Salt Lake Telegram, June 30, 1916: 6.

51 Polk’s Memphis (Shelby County, Tenn.) City Directory 1938 (Detroit: R.L. Polk & Co., 1938), 625.

52 “Human Lightning Rod from Pacific Coast League Signs with Yankees”; “Slim Love Discovers a New Use for Mud Hens,” Los Angeles Times, December 11, 1914: Part III, 1.

53 George White, “The Sport Broadcast,” Dallas Morning News, January 31, 1930: 12; “Necrology,” Sporting News, December 10, 1942: 18.

Full Name

Edward Haughton Love

Born

August 1, 1890 at Love, MS (USA)

Died

November 30, 1942 at Memphis, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.