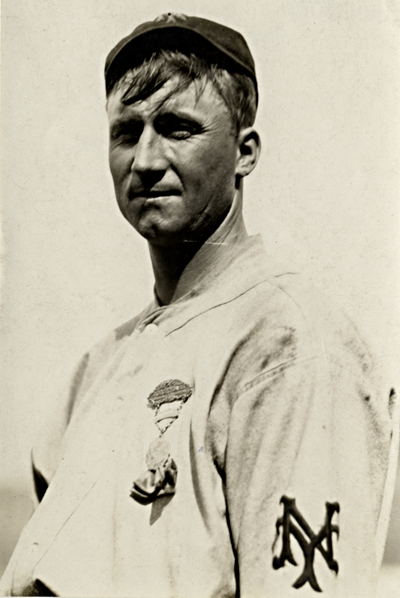

Charlie Faust

In the annals of baseball history, the tale of Charles Victor “Victory” Faust is virtually unmatched for sheer strangeness and improbability. Arguably the least athletic person apart from Eddie Gaedel to play in the major leagues, Faust pitched in two games for the 1911 New York Giants and contributed two stolen bases to their record-setting total of 347. Before those game appearances, however, Faust made his mark as John McGraw‘s good-luck charm and mascot. His invincible jinxing powers inspired the Giants to win the National League pennants of 1911 and 1912, after which his luck ran out and he faded into oblivion for a half-century.

In the annals of baseball history, the tale of Charles Victor “Victory” Faust is virtually unmatched for sheer strangeness and improbability. Arguably the least athletic person apart from Eddie Gaedel to play in the major leagues, Faust pitched in two games for the 1911 New York Giants and contributed two stolen bases to their record-setting total of 347. Before those game appearances, however, Faust made his mark as John McGraw‘s good-luck charm and mascot. His invincible jinxing powers inspired the Giants to win the National League pennants of 1911 and 1912, after which his luck ran out and he faded into oblivion for a half-century.

Faust was born in Marion, Kansas on October 9, 1880, the oldest of six children of John and Eva Faust. John Faust was German, and Charles inherited his thick German accent. Sadly, the parents outlived four of their children. Freddy died in infancy, Fred died as a teenager, Louise (the only daughter and the only one to have a child) lived only thirty-two years, and Charles died at thirty-four. The two survivors were John and George, who took over management of the family farm from John Sr. Charles, a slow-witted lad at best, was incapable of running the farm, making him a sore disappointment to his stern father. Little is known of his youth except that it must have been bleak; a child of the plains, he was not compatible with the land and had no discernible abilities or prospects for improving his lot.

Until one day in the summer of 1911, that is, when a trip to the county fair changed his life. At the end of July, when Faust traveled to St. Louis and introduced himself to John McGraw, he spun a tale of being told by a fortuneteller that he would pitch the Giants to the championship. The supremely superstitious McGraw gave the gawky (6-foot-2, 180 pounds) thirty-year-old a tryout. It was quickly apparent that Faust was not a ballplayer, so McGraw had a joke at his expense, conning him into circling the bases while the Giants infielders threw the ball away so he would slide into each base. He wound up at home plate covered with dust, his Sunday clothes torn and his skin raw, but the Giants won 9-0 that day, and when he showed up the next day, they let him cavort on the field again before the game. They won again and repeated the routine for a third day, but when they left St. Louis, McGraw gave Faust the run-around at the train station and continued on without him. After struggling through the rest of the trip, they returned to New York and found the eager Faust waiting for them at the Polo Grounds.

Faust had exactly enough brain-power to grasp firmly the one notion planted in his head by the fortuneteller, namely that he was destined to pitch the Giants to the title. Nothing could shake him from that conviction, as the events of the next two months proved. His success had nothing to do with athleticism; describing his first appearance in uniform at the Polo Grounds, John Wheeler of the New York Herald wrote, “he runs like an ice wagon and slides as if he had stepped off a trolley car backward. He plays ball as if he were a mass of mucilage.” With Faust on hand, the Giants swept a doubleheader that day, and the Faust legend was born.

In short time, Faust became the star of the extended pre-game activities. He would shag fly balls (getting conked on the head more than once), demonstrate an array of clumsy slides, and pitch some batting practice, during which opponents including Honus Wagner would let him strike them out with his feeble tosses. Once the game started, Faust would either station himself beyond the outfield, warming up for innings at a time to be ready in case the Giants needed him, or sit on the bench, cheering on his teammates and predicting their base hits. Whatever he did worked. From the time he met McGraw in St. Louis to the day the Giants clinched the pennant, the team had a record of 39-9. When he was in uniform and exerting his jinxing powers, their record was an astonishing 36-2. There were some interruptions in his tour of duty. When McGraw refused to let him pitch in a game after his arrival in New York, he fled to Brooklyn for a couple of days to offer his services to that team, but returned to McGraw after being rebuffed. After three weeks in New York, he was so popular that he signed for a vaudeville engagement. When the Giants failed to win during his first three days treading the boards, he abandoned show business to return where he was truly needed, in time to join the team on a 22-game road trip. Naturally, they won the first ten games on the road, not losing until the second game of a doubleheader in St. Louis when local sportswriters detained him after the first game for an extended interview. That’s what it took to beat the Giants when Faust was with them.

Despite the team’s success, Faust was frustrated in his aim to fulfill the prophecy completely. No matter how many times he implored McGraw to let him pitch, the manager kept stringing him along. McGraw knew it would be a travesty to let Faust into a game, but he also saw how Faust’s presence benefited the players. Good-natured and gullible, impervious to ridicule, Faust became the butt of incessant practical jokes, providing a humorous balance to McGraw’s harshness that kept up team morale. It wasn’t long before the players believed in his infallible jinxing abilities. Even Red Ames, dubbed “Kalamity” because of persistent bad luck, became a Faust convert; early in that September road trip during which the Giants went 18-4 and clinched the pennant, Ames declared, “I’m glad Faust is going to stick because he certainly has brought good luck to us all. . . .he is a great man for the team even if he never gets a chance to pitch.”

Somehow, despite his fixation on fulfilling that prophecy, Faust managed to answer the needs of all New York baseball constituencies. He kept the players loose, he entertained crowds before the game, he helped McGraw move up in the National League standings, and he became the darling of the big-city sportswriters. There were thirteen daily newspapers in New York City, and reporters fighting for colorful material found a goldmine in Faust. They championed his ambitions, described his antics, reported the pranks, and delighted in the tug-of-war between Faust and McGraw. Chief among his boosters were Sid Mercer of the Globe, who sometimes carried two or three items a day about Faust’s diversions, and Damon Runyon, a fellow Kansan newly arrived in New York that year, who seized on the novelty of this character and by season’s end had him sounding like an early version of Nathan Detroit. After the Giants clinched the pennant with six games left on the schedule, they saw no reason for McGraw to prevent Faust from living out that prophecy in full.

Finally, McGraw relented, putting Faust in to pitch the ninth inning against Boston at the Polo Grounds. Bill Rariden greeted him with a long double, but he got lucky after that. Pitcher Lefty Tyler bunted Rariden over, and another long fly ball was caught, Rariden scoring. Then Mike Donlin, laughing along with the crowd at Faust’s weak-armed heaves, grounded out. In the bottom of the ninth, Faust was on deck when the last out was made; however, as John Wheeler put it, “what are three outs to Faust?” Boston stayed in the field and let Faust bat, putting him through the same bases-circling routine McGraw did that first day back in St. Louis, until he was tagged out just shy of home plate. Faust left the field triumphant; against all odds, he had indeed pitched for the Giants and led them to the National League title. Five days later, he pitched again, the final inning of the season, and held Brooklyn scoreless. This time, he came to bat in turn in the bottom of the ninth, was hit by a pitch intentionally and allowed to steal second and third before scoring on a squeeze bunt to complete the burlesque.

Unfortunately, Faust’s run of good luck stalled in the World Series; the Giants faced the Philadelphia Athletics of Connie Mack, who employed an experienced mascot, a hunchback dwarf named Louis Van Zelst. Van Zelst out-jinxed Faust, and with a little help from Home Run Baker, the Athletics defeated the Giants in six games. His bubble burst, Faust saw his stock fall further in mid-November when he had a disastrous second try at vaudeville. Playing at Willie Hammerstein’s Victoria Theater, Faust performed so horribly in his first show that the next act refused to follow him again. The reviewer in Variety stated that “Vaudeville must be desperate when it will attach an ‘act’ of this sort to itself; also vaudeville must be lifeless to endure it.”

After wintering back in Marion, Faust went on his own to Hot Springs, Arkansas, in February of 1912, attaching himself to Bill Dahlen’s Brooklyn Superbas at spring training. His stated aim was to learn to pitch left-handed so he would be twice as valuable to McGraw, though McGraw seemed surprised to learn that Faust intended to rejoin the Giants. On February 29, 1912, Faust was allowed to pitch an entire game in Hot Springs, holding the opposition to four runs and further cementing the notion in his mind that he could be a real pitcher if given the chance. When camp broke, he foisted himself on McGraw again, and though the Giants no longer consented to pay his expenses on road trips, he was allowed to cavort as usual at the Polo Grounds.

Is it any surprise, then, that the 1912 Giants got off to one of the best starts in history? By late June they had a record of 54-11, setting the standard that was chased in 2001 by the Seattle Mariners. Adding that to their record after Faust’s arrival in 1911, the Giants won over 80% of their games during his tenure with the team. However, his insistence in 1912 that he really was a pitcher wore thin on McGraw, who came to regard him as no longer a laughable innocent but as a demented threat. He tried to get Faust to leave, but it took some devious persuasion by the players to get Faust to return to Kansas, ostensibly to await the inevitable summons from McGraw once it became clear how helpless the Giants were without him.

Indeed, as soon as Faust left, the team’s fortunes turned, notably those of Rube Marquard, whose record was 33-2 while Faust was around. Marquard won his first nineteen decisions in 1912; in the week after Faust’s departure, he lost three times, and he was a sub-.500 pitcher the rest of the season. Even though much of the team’s lead in the standings evaporated, McGraw had no intention of bringing Faust back, and the team wound up winning the pennant again and losing the World Series again without their good-luck charm.

Faust never got near the major leagues again, though it wasn’t for lack of trying. Over the next two years, he peppered McGraw and the National League office with requests for reinstatement on the team, with back pay for his contributions to their pennants. He moved to California, did odd jobs, then joined his brother John in Seattle, all the while petitioning for his return to New York. Gradually the delusion that he was a legitimate pitcher being deprived of his true destiny overtook him. In July 1914, no doubt sensing that the Giants were being threatened by the rise of the “Miracle Braves,” he attempted to rejoin them. However, he did so by walking from Seattle to Portland, where police found him wandering the streets in a daze. After a hearing, he was sent to a mental hospital in Salem, where he listed his occupation as “professional ballplayer” on the admission form. After seven weeks in that institution, where he was diagnosed as suffering from “dementia,” he was deemed “not improved” but released into his brother’s custody. They returned to Seattle, but in December he was remanded to the Western State Hospital in Fort Steilacoom. On June 18, 1915, he died of tuberculosis, though it is unknown whether he had the disease before he was institutionalized or whether he contracted the disease there. He was buried in an open field across from the hospital, and his story appeared to be buried along with them.

Faust disappeared from public notice for fifty years, until Lawrence Ritter interviewed Fred Snodgrass, the center fielder on the 1911-12 Giants. In The Glory of Their Times, Snodgrass recounted the Faust story, though he got many of his “facts” wrong, most notably stating that Faust stayed with the Giants for three years and did not appear in vaudeville until that third season. Despite the inaccuracies, Snodgrass spun a captivating tale of this real-life Forrest Gump, who through audacity more than ability had a significant impact on the Giants. Since then, Faust has become a cult figure amongst baseball aficionados, deservedly so considering the incredible performance of the Giants under his influence.

Sources

Burkholder, Edwin V. “The Curious Case of Charley Faust.” Sport. 8:6 (June 1950).

Busch, Thomas S. “In Search of Victory: The Story of Charles Victor (‘Victory’) Faust.” Kansas History. 6:2 (Summer 1983).

Mathewson, Christy. Pitching in a Pinch. New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1912.

McGraw, John. My Thirty Years in Baseball. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995.

Ritter, Lawrence. The Glory of Their Times. New York: Macmillan, 1966.

Schechter, Gabriel. Victory Faust: The Rube Who Saved McGraw’s Giants. Los Gatos, California: Charles April Publications, 2000.

Seymour, Harold. Baseball: The Golden Age. New York: Oxford University Press, 1971.

Newspapers from Arkansas, Boston, Brooklyn, Chicago, Cincinnati, New York,

Philadelphia, Portland (Oregon), Seattle, St. Louis, Tacoma, and Topeka, as well as Marion County, Sporting Life, Sporting News, and Variety.

Player files at the National Baseball Library in Cooperstown, New York: Red Ames, Beals Becker, Al Bridwell, Doc Crandall, Eddie Dent, Art Devlin, Josh Devore, Mike Donlin, Larry Doyle, Louis Drucke, Steve Evans, Art Fletcher, Grover Hartley, Buck Herzog, Arlie Latham, Rube Marquard, Christy Mathewson, Bert Maxwell, John McGraw, Fred Merkle, Chief Meyers, Red Murray, Bill Rariden, Bugs Raymond, Wilbert Robinson, Fred Snodgrass, Lefty Tyler, Art Wilson, Hooks Wiltse.

Full Name

Charles Victor Faust

Born

October 9, 1880 at Marion, KS (USA)

Died

June 18, 1915 at Fort Steilacoom, WA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.