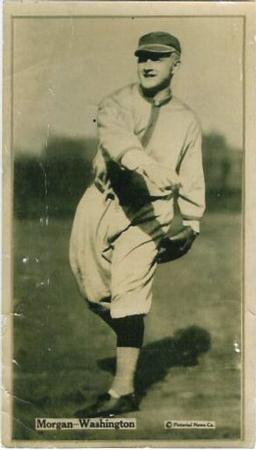

Ray Morgan

Getting caught stealing forever links Ray Morgan to Babe Ruth and Ernie Shore. Getting out of jail — a month into a year’s sentence — when Clark Griffith showed up in court with a scouting job offer — is another reason Morgan has a place in the game’s lore.

Getting caught stealing forever links Ray Morgan to Babe Ruth and Ernie Shore. Getting out of jail — a month into a year’s sentence — when Clark Griffith showed up in court with a scouting job offer — is another reason Morgan has a place in the game’s lore.

Morgan played second base for the Washington Senators in the final decade of the Deadball Era alongside slick-fielding shortstop George McBride. Morgan often was sidelined by injuries but played mostly on a regular basis from 1912–17. He was used less in 1918, his final season, having lost favor with Griffith, who was still the field manager at the time.

On June 23, 1917, in Boston, Morgan played a pivotal role in one of baseball’s most famous games. He led off the game by drawing a walk from Ruth, the Red Sox starter. Ruth was so incensed by the calls, he punched the umpire and was ejected. Shore took over on the mound, and Morgan was immediately thrown out trying to steal. Shore famously retired the next 26 batters in a row, a feat that until 1991 was deemed a perfect game.1

Carville Ray Morgan, the youngest of six children, three girls and three boys, was born on June 14, 1889, in Baltimore, which he called home all his life.2 His parents were Baltimore natives George A. Morgan and the former Margaret Jones. George listed his occupation in the 1900 census as a clerk of some sort. Margaret, who went by Maggie, was a housewife. Census records indicate the Morgan family was of modest means, with parents, in-laws, and boarders part of an extended household in a rented home in Baltimore’s Waverly neighborhood. 3.

“Has Been Active in Athletics Since He Was Little Boy,” read the subhead of a 1913 newspaper story about Morgan’s early years. “Ray has been an athlete all his life,” a person identified only as “a Baltimore admirer” told the Washington Times, which referred to the player as “Cutie Carville.” That nickname appeared frequently in the Washington papers during his years with the Senators.

Ray used his agility to earn money at an early age. “The little fellow used to be an acrobat” to entice people to pay five cents to go in and see local stage shows, the admirer told the Times. Young Ray “could ‘skin the cat,’ ‘bend the crab,’ ‘handspring,’ ‘cartwheel,’ and walk on his hands…. Ray has always been a real sociable sort of chap, and always had a host of friends.”

Morgan “learned to play on what used to be called the brickyard at Waverly,” the Times said. Ray first attracted attention as a catcher for the Eureka Life Insurance club, a top-flight semi-pro team that played on weekends in Baltimore. He eventually played for at least half a dozen semi-pro teams in and around Baltimore. “He was improving all the time.”4

Where, or if, Morgan attended high school is uncertain. Baltimore Polytechnic and Baltimore City College, both of which still exist and were the only two public high schools for white male students in the city in the early 20th century, have no record of Morgan. At least one source lists Ray as having attended Frederick Douglass High, which is unlikely because at the time that school was named “Baltimore Colored High School”. In any case, he continued to live with his parents in Baltimore at age 20 as his professional baseball career was getting started.5

Young Ray, who threw and batted right-handed, stopped growing when he reached 5-feet-8. His listed height might have been exaggerated. He was often described in pro ball as “little” or “diminutive” in an era when many players were well under six feet. Some newspaper stories gave his height as 5-feet-6.6

Morgan’s “reputation as a player began when he played with the Waverly Club of the Suburban League in 1908,” the Baltimore Sun wrote in 1918. By this time, he was a shortstop. A semi-pro team he was with in 1910 played a series of games in Virginia in which he attracted attention. As a result, Ray signed during that season with Goldsboro in the Class D Eastern Carolina League, where he hit .239. C. Norman Willis, author of Washington Senators’ All-Time Greats, wrote that Morgan also played for Frederick, Maryland, in the Blue Ridge League and later with Danville in the Class C Virginia League that same season. The Frederick team was a high-level semi-pro squad organized and managed by a wealthy Maryland politician.7

Morgan’s .334 average with Danville in 1911 was leading the league when scout Duke Farrell negotiated Morgan’s purchase for the Washington Senators on July 26 for $1,500. He made his debut with the team as a sub in a blowout loss to the Browns on August 7, drawing a walk and scoring a run in three plate appearances in his first MLB game. “He was held on the bench for four weeks,” Morris A. Bealle wrote in his 1947 team history. “When he was finally allowed to play, [he] proved himself of major league caliber.”8

Morgan started his first game, playing third base, on August 21 against the White Sox in Chicago. He started at third again the next day and got his first hit, a single off Doc White, and first RBI. He ended the season playing in 25 games, all at third base, but hit just .213 and committed eight errors.

A new era began for the Washington club in the 1911-12 offseason. Clark Griffith was hired as manager and was able to buy10 percent ownership of the team. Before long, he began jettisoning most of the veterans of the also-ran Senators, with the exceptions of Walter Johnson, Clyde Milan, and McBride. Griffith knew he had a solid pitching staff but was determined to give several young players a chance to show what they could do: Morgan was one of them. In camp, the new manager tried Eddie Foster at third and Morgan at second. “He worked both men out … only at their new positions, and when spring concluded, they looked good.”9

Although he was able to adjust, Morgan said during the season it was “pretty hard work to switch to the right side.” Griffith, aside from shepherding the position switch, “taught me how to bat,” Morgan said. Still, he rode the bench most of the first month of the 1912 season, starting just two games at short after McBride, hit by a pitch, was sidelined. Griffith played the veteran John Knight at second base until the former Yankee proved he could no longer hit much and was released.10

Morgan started just once at second before being inserted there in the second game of a doubleheader in Boston on May 30, the day Washington began what would be the franchise’s longest winning streak. Walter Johnson shut out the Red Sox on five hits. Morgan was 2-for-4 to raise his average to .304. He hit his first big league homer, an inside-the-parker, on June 6. When the Senators’ win streak ended on June 19in first game of a doubleheader, Morgan was hitting .337. He had been on a tear. During the streak, Morgan hit .349 (22 for 63) with a .403 OBP. Washington had climbed from sixth place to second — a place it had never before been — a game and a half behind league-leading Boston. Newspapers began to refer to the team as the “Climbers.”

Morgan cooled off after the hot streak. He was out of the lineup for five days at the end of June, complaining of leg cramps. Washington lost five of the six games he missed, but he was back at second on July 2 and still hitting .291. His return coincided with the start of another Nats winning streak, this one 10 games long. Sports writers began calling Morgan the Senator’s “watch charm.” A sports columnist recalled the day after Morgan died, “When he entered the game the luck always changed … for the best.”11

The second baseman went just 6 for 31 during the second winning streak, but he walked eight times for a .359 OBP. His batting average continued to slip, however, from .266 when the 10-game streak ended on July 10 to .238 at the end of the season. “Ray Morgan was having trouble keeping in condition and he slumped accordingly,” Bealle wrote. Although Morgan remained in the lineup most days, it was by no means certain he would play regularly in 1913. Morgan had other ideas. “I’m ready,” he told a reporter just before the start of spring training. “I just want to show Griff and the rest of you guys that they will have to count on me for that second base job.”12

The same Washington Herald story from February 1913 mentioned Morgan’s skill in another sport. “Morgan has been keeping in shape bowling and … developed into a crack duckpin shooter.” That season, Morgan and four teammates formed a duckpin bowling team that competed locally over the next few seasons. The second baseman also persuaded Griffith to take up bowling. “Morgan is a great duckpin bowler,” the Washington Post observed in May 1915. By the 1914 season, Morgan was bowling in several different leagues in Baltimore and Washington. He later took an off-season job at a Washington bowling alley.

Morgan arrived in 1913’s camp in good condition, which was often was a problem throughout his tenure in Washington. A solid spring won Morgan a lineup spot on opening day. He went on to have what turned out to be his best season and began to draw plaudits from competitors. Two future Hall of Famers sang his praises.” Morgan ought to be one of the best second baseman in the game before he slows down,” George Davis thought, and Nap Lajoie adjudged him as behind only Eddie Collins among A.L. second sackers. “In a couple of seasons I believe (he) will be the leading second baseman in the league.”13

Morgan was hitting over .300 with an on-base percentage north of .420 when the two great infielders predicted a bright future for him. As he did in 1913, however, he tailed off as the season wore on. Still, he started 134 games at second base. Teaming with McBride, he led the league in double plays turned at his position. He hit a career-high .272 with a .369 OBP, thanks to 68 walks — eighth best in the AL.

During the 1913 season, he began to draw Griffith’s ire, who didn’t like Morgan’s frequent trips home to Baltimore by automobile to socialize with his friends. Travel by car, even the 30 or so miles between Washington and Baltimore, could be an adventure in those days. Morgan also developed a reputation as a fun-loving cut-up on road trips. He was an accomplished piano player, able to accompany any song his teammates wanted to sing. He’d break out in song by himself in hotel rooms or on trains “in that high tenor of his,” often in conjunction with a teammate or two. When these performances came late at night, they surely would not have pleased Griffith, a stickler for training rules.14

Spring training in 1914 was the first of several to which Morgan reported well over his playing weight. Although a March 24 report praised his pre-season hitting, it noted that “Morgan is still considerably overweight.” He again started at second base on opening day. Morgan “Chevrolets to Baltimore and back twice a week,” the Washington Times wrote. Driving a car still was unusual enough that when Germany Schaefer, his roommate on the road, joined Morgan as an automobile owner, it was news. So was Griffith’s concern for his player’s safety.15

The concern proved warranted. On April 10, Morgan’s auto collided with a Baltimore trolley car. He and two friends were on their way back to Washington. Morgan and another man were thrown from the automobile. All three men were shaken up but uninjured. “The machine was so badly damaged that it had to be abandoned,” a newspaper reported.16

Morgan got off to a terrible start in 1914. Although he stayed in the lineup — he started 147 of the 154 games — his batting average remained under .200 as late as June 3. A hot streak from late June to late July got him into the .250s, but then he went cold again. By going 13-for-33 in his last nine games, he was able to finish his uneven season at .257 with a .352 OBP. He was hit by 10 pitches and drew 62 walks, accounting for his respectable OBP.

On July 30 in Detroit, Morgan was at the center of one of the worst riots involving players, spectators, and police at a 20th century major league game. The umpire, Jack Sheridan, was a respected veteran, but his failing eye-sight meant he no longer worked behind the plate. Called out on a close play at first base, Morgan threw dirt at Sheridan’s feet. The umpire immediately ejected Morgan before decking him with a punch. Morgan got up and began swinging at the umpire.Griffith, coaching third, and McBride rushed to try to pull the two apart. As McBride was trying to restrain Sheridan, Eddie Ainsmith, the Nats’ catcher who was coaching first, landed a glancing blow on the umpire. Ainsmith also was ejected.17

By this time, members of both teams had come out of their dugouts. As Morgan and Ainsmith headed off the field, spectators began yelling abuse at Ainsmith as he approached the stands. A fan and the player began exchanging blows before the fan picked up a chair and heaved onto the field, hitting one of the Nats. The fans behind the Detroit dugout came out of the stands and began pummeling Morgan. Several players on both teams came to his rescue.

At this point, people from the bleachers were running across the field toward the brawl. The police from a station adjacent to the ballpark arrived in force. With the help of the players, they got the fans back into the grandstands. The Senators demanded that the fan who threw the chair be arrested, but the police declined. Detroit owner Frank Navin showed up and persuaded several belligerent spectators to leave. Despite an appeal from Griffith, no action was taken against Sheridan, who suffered sun stroke during an August game and died that fall. Morgan was suspended for a week and Ainsmith for two.18

“Ray was a shade below his proper form last year … probably due to carelessness,” the Sporting Life wrote of Morgan’s 1914 performance. Griffith “believes that Morgan didn’t take the best care of himself last year,” the Washington Times observed.19

As the season ended, Morgan took a job selling cars at a Chevrolet dealer in Washington. Part of the deal was his purchase of a “Chevrolet ‘baby grand’ touring car.” Griffith tried to get Morgan to remain in Washington in the off-season to work out at Georgetown University: “Ray puts on weight so fast that it will do him a world of good.” Morgan, however, declined and promised to work out at a gym in Baltimore. Griffith was skeptical. “If that bird reports hog fat … he’ll do twice as much work as any other man” in camp, the manager promised. As the Old Fox predicted, Morgan showed up overweight and struggled to get the pounds off.20

“If my job depends on it, I’m going to get down into perfect shape,” Morgan promised, “and then make all other candidates hustle for that second base job.” Once again, Morgan managed to get into good enough shape to make into the opening day lineup. He rewarded his boss with a perfect day at the plate, driving in four of the seven Nats runs to back up Johnson’s two-hit shutout of the Yankees.21

By the end of April, however, Morgan was hitting .213. A solid May raised his average into the .250s, but he tailed off again in June. After Washington lost, 3-2, to the A’s on June 26, Morgan was hitting .232. His declining batting average turned out to be the least of his troubles.

On the morning of June 28, a friend was driving Morgan’s Chevrolet back to Baltimore with Morgan as a passenger when the automobile slide into a ditch. Both men were thrown out and suffered what Morgan described as cuts and bruises. He blamed oil on the road for the accident. When Morgan called Griffith to say he would miss a few days because of an injured knee, the boss was livid and immediately suspended him without pay. “The Nationals leader has insisted that Morgan would be better off without an automobile, but this only caused Morgan to get rid of his little car and get a big one,” the press reported.22

“I have been lenient with Morgan,” Griffith said. “He has held my ball club back all year by running around and not taking care of himself. I do not want that kind of man on my club.” Stanley T. Milliken of the Washington Post wrote that the Senators’ skipper might just be using tough love on Morgan because “the Nationals chieftain has always been rather sweet on his second sacker.”23

But the beat writers of two other Washington dailies were less sanguine. “It is generally thought that Morgan is done so far as Washington is concerned,” reported Lou Dougher of the Washington Times. J. Ed Grillo of the Evening Star concurred, commenting that “The recall of Morgan … will not be beneficial to the discipline of the Nationals. For some unaccountable reason, the Baltimore infielder seems to get away with more things than anyone else.”24

Griffith ordered Morgan to report for duty with the team in Boston a week after the auto accident. When he arrived, it was clear he was not fully recovered, “far from being in condition to play,” according to Dougher. But despite a lingering knee injury and added weight, Morgan started at second base on July 10 in a tie game that ended after five innings. He handled two grounders cleanly, turning one into a 4-6-3 double play. He managed a single and scored the Nats only run in two plate appearances. Any chance he would get back in Griffith’s good graces, however, was squelched before the game. In a dispute over ribbing that got out of hand, Morgan punched teammate Joe Boehling in the mouth. Others intervened before Boehling could retaliate. Griffith fined both players $50 and warned that a repeat would get them suspended.25

After starting 55 of the first 57 games of 1915 at second, Morgan was relegated to the bench until a pinch-hitting appearance on August 29. He didn’t start a game until September 9, when he played second base in the second game of a twin bill. He started at shortstop in the season’s final game. He had not been missed: Washington stood at 28-27 after Morgan’s last game before his suspension, but went 57-39 after that, finishing fourth with 85 wins.

Still, replacing Morgan at second had forced third baseman Foster and leftfielder Howie Shanks to play out of their normal positions, so it looked like Morgan might get yet another chance in 1916. “Griff said …that Morgan would most likely be given another trial, provided he reported to training camp in good shape,” the Baltimore Evening Sun reported in December 1915.26

After once again working himself into shape, Morgan won his job back in the spring and was in the 1916 opening day lineup in New York. He led off and drove in the winning run, the second of his pair of RBIs and the last of his three hits in an 11-inning 3-2 win over the Yankees. Morgan shared the headlines in the next day’s papers with The Big Train, the Nats perennial opening day starter, who went the distance.

As in previous seasons, Morgan cooled off after a hot start but played regularly until he suffered a severe ankle sprain sliding into second on June 23. He missed all of July. When he returned August 1, the rust showed, and his average fell briefly to .242. He kept getting on base regularly, however, finishing the season with the league’s fourth best on-base percentage (.398) behind only Tris Speaker, Ty Cobb and Eddie Collins. By hitting .370 over his last 13 games, Morgan raised his batting average to .267 by season’s end.27

Despite what seemed like a solid season from Morgan, Griffith seemed to have made up his mind that Ray was no longer a good enough second baseman. He “has his doubts about Morgan being a player who can keep himself in perfect condition,” Grillo wrote.” But Griffith wasn’t able to trade Morgan, and once again, Ray had to work hard to get back into shape in spring training. Although he wasn’t in the 2017 opening day lineup, he was playing second base regularly by May 1. An ankle sprain slowed him, but he was back and leading off by June 23, the famous Ruth-Shore no-hitter. Another leg injury kept him out for two weeks, but he returned in time to get the only Washington hit off Eddie Cicotte on July 17.28

The next day, the ankle injury that had never fully healed put him on the shelf again for nearly a month. Although he missed about seven weeks in 1917, he played in 101 games, starting 97 of them. He hit .266 with a .346 OBP. Sometime during that year, Morgan became owner of what newspapers described as a café on Greenmount Avenue in Baltimore. In an application for a liquor license, however, the “café” was described as a saloon. And in the first month of 1918, Morgan took a significant step when he married Florence Irene Gaffard of Bladensburg, Maryland, a Washington suburb. They had a daughter, Marie, born in 1920.29

Griffith couldn’t find a suitable replacement, so in 1918, Morgan was again Washington’s opening day second baseman. But in this season shortened by the U.S. entry into World War I, Morgan never did get hot. Shanks replaced him for three weeks at second. Yet the Nats won 31 of their last 47 games with Morgan playing second more often than not. He hit .233 for the year. When the season ended on September 1, Morgan told reporters he was returning to Baltimore to run his café. He would never appear in the majors again.30

On February 1, 1919, Griffith sent Morgan to the Phillies for the $2,500 waiver price. Wanting to stay close to home, Morgan said he wouldn’t report. After some negotiation, the Phillies sent him back to Griffith who released the player to the Baltimore Orioles. Morgan started the season with his hometown minor league club, but after a fight with a teammate in June, he abruptly quit.

Morgan’s life took several dark turns after he left professional baseball. Though he signed with AAA Akron in 1920, he never played there. Prohibition likely took a toll on his café/saloon. In April, he was playing semi-pro ball on weekends with the Sparrows Point team in the strong Bethlehem Steel League. Florence divorced him in 1921. He played for at least two more semi-pro teams through the 1923 season. In May 1922, authorities found parts of a still, some whisky, and 125 gallons of mash, a necessary ingredient in bootleg liquor, were found in Morgan’s rented home. It’s unclear whether he ever faced charges.31

In December 1923, Morgan and another man were charged with beating up a Baltimore police officer, leaving him unconscious on the street, for which, on February 15, 1924, Morgan was sentenced to a year in prison. But in late April, Griffith showed up in court with a job offer and an eloquent plea for Morgan’s release. The Nats owner promised to guarantee Morgan’s good behavior and to employ him as a scout. Morgan remained on Griffith’s payroll at least through 1925.32

But he wasn’t able to stay out of trouble. He was arrested during a disorderly party in Baltimore on March 14, 1928. Morgan along with two men and two women were charged with disturbing the peace. In October 1933, he was sentenced to three months in jail for beating a woman who owned the store where he and another man had been drinking.33

In February 1940, Morgan was admitted to a Baltimore hospital suffering from pneumonia and heart trouble. “He also appeared to have been in an accident of some kind, for he had injuries of the knees, the thigh, the left side of his face and left arm,” the Baltimore Evening Sun reported. Morgan died in the hospital several days later, on February 15, 1940. He was 50 years old.34

“He was as smart as ballplayers come on the field,” said the Senators’ Joe Judge (who as a rookie roomed with Morgan) in an obituary. Despite his disputes with Morgan, Griffith too was generous: “I never knew a more spirited player. He made himself a big leaguer on hustle.”35

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Paul Doutrich and Tom Schott, and fact-checked by Bob Boehme and Chris Rainey.

Sources

https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/m/morgara01.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/M/Pmorgr101.htm

Notes

1 John McMurray, “100 years later: looking back at Ernie Shore’s ‘perfect game,’” accessed April 10, 2020,https://sabr.org/latest/mcmurray-100-years-later-looking-back-ernie-shores-perfect-game.

2 Morgan listed his birth year as 1890 on his World War I draft registration form.

3 Mother’s maiden name is listed on Morgan’s death certificate in his player file at the Hall of Fame and Museum.

4 Previous paragraphs based upon “Tells How Morgan Started Baseball,” Washington Times, August 19, 1913: 10.

5Telephone conversation, author with Sarah Jean Blanc, Baltimore City College, and with representative of Baltimore Polytechnic alumni office, January 9, 2020; www.baseball-almanac.com/players/player.php?p=morgara01; 1910 U.S. Census.

6 “Ray Morgan, Former Nat Star, Dies at 47,” Washington Post, February 16,1940: 22. This story lists Morgan’s age incorrectly, and reports his height 5-feet-6.

7“Now in Matrimonial League,” Baltimore Sun, January 18, 1918: 12; Willis, C. Norman, Washington Senators All-Time Greats (Xlibris Corp., Washington, D.C., 2003): 153; “Can’t Oust Browns,” Baltimore Sun, June 18, 1912: 12.

8 “Ray Morgan Sold,” Baltimore Sun, July 27, 1911: 9; Morris A. Bealle, Washington Senators (Columbia Publishing Co., Washington D.C., 1947): 88.

9 Ted Leavengood, Clark Griffith (McFarland & Co., Inc., Jefferson, N.C., 2011): 94.

10 “Can’t Oust Browns,” Baltimore Sun, June 18, 1912: 12.

11William Peet, “Morgan Says ‘Watch Me, Boys’ Washington Herald, February 26, 1913: 8; Frank Colley, “The Colley-See-Um of Sports,” Hagerstown [Md.] Morning Herald, February 16, 1940: 16.

12Bealle, Senators, 91; Peet, see note above.

13“George Davis Praises Griffith’s Ball Club,” Washington Herald, July 13, 1913: 34; “Morgan Lauded by Larry Lajoie,”, Pensacola FL] News Journal, July 14, 1913: 6.

14“Baseball Notes,” Pittsburgh Press, March 20, 1913: 19; “Climbers Possess Night Comedians,” Washington Times, August 28, 1913: 10

15Thomas Kirby, “Nationals Obtain Plenty of Practice,” & “Griff Insure Every Player On His Team; Will Take No Chances,” Washington Times, March 24, April 2, 1914: 10, 11.

16 “Ray Morgan Near Death in Crash,” Washington Times. April 11, 1914: 12.

17 Stephen V. Rice, “Jack Sheridan” https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/1eea055b.

18 Bealle, Senators, 96; Stanley Milliken, “Morgan Back at Second Base,” Washington Post, August 6, 1914, 8.

19Paul W. Eaton, “At the Capital,” Sporting Life, March 13, 1915: 6; Louis A. Dougher, “Ray Morgan to Go South With Martin on Tuesday,” Washington Times, February 19, 1915: 15.

20“Will Sell Chevrolets,” Washington Evening Star, September 27, 1914: 25; Dougher, “Expect Ray Morgan to Begin Training on Hilltop Field,” Washington Times, February 9, 1915: 10; see note above, Dougher.

21 Dougher, “Johnson Arrives at Camp Ready to Uncork Twisters,” Washington Times, March 8, 1915: 12.

22 “Ray Morgan Is Injured, Suspended,” Pittsburgh Press, June 29, 1915: 28.

23 Ibid.; Stanley T. Milliken, “Neff May Play Second Remainder of Season,“ Washington Post, June 28, 1915: 8.

24Dougher, “Morgan Will Not Go With Team When It leaves Here,” Washington Times, June 29, 1915: 10; J. Ed Grillo, “Ray Morgan Ordered to Join Nationals in Boston,” Washington Evening Star, July 3, 1915: 8.

25Dougher, “Joe Lannin Popular With Boston Public,” Washington Times, July 6, 1915: 11; “All Except Johnson Are on the ‘Market’,” Washington Post, July 11, 1915: S1.

26 “Ban Plans to Keep Somers in League,” Baltimore Evening Sun, December 27, 1915: 9.

27 Stanley T. Milliken, “Notes of the Nationals,” Washington Post, June 24, 1916: 8.

28J. Ed Grillo, “Tigers Take Lead in Race, Red Sox Dropping to Third,” Sunday Star, September 17, 1916: S1; “Ray Morgan Back in Game, Gets Only Hit Off Cicotte,” Washington Post, July 18, 1917: 8.

29“Sale of Saloon Ordered,” Baltimore Sun, December 18, 1917: 8; “Morgan, Of Nationals, Joins Benedict League,” & “Suburban,” Washington Post, January 11, 1918 & July 13, 1921: 21, 3.

30 J.V. Fitzgerald, “The Round-Up,” Washington Post, September 2, 1918: 6.

31 “Akron Takes Morgan,” Baltimore Evening Sun, March 9, 1920: 16; “Suburban,” see note 29; “Still in Ball Player’s Home,” Baltimore Sun, May 4, 1922: 3; 1920 U.S. Census.

32 “Clark Griffith Wins Release of Former Player From Jail,” New York Times, April 30, 1924: 17.

33 “Former Ball Player Charged With Assault,” Frederick MD] Daily News, December 18, 1923: 6

34 “Ray Morgan, Ball Star of 30 Years Ago, Dies,” Baltimore Evening Sun, February 15, 1940: 10.

35 “Ray Morgan . . . Dies,” see note 5.

Full Name

Raymond Caryll Morgan

Born

June 14, 1889 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

Died

February 15, 1940 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.