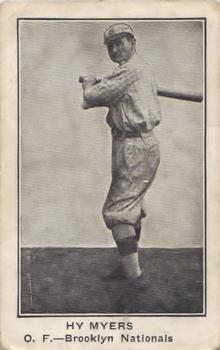

Hy Myers

Effective as a leadoff man or in the middle of the lineup, Hy (or “Hi”) Myers was a speedy center fielder whose unique running style made him popular with fans wherever he played. “Myers galloped with his long arms held straight down by his sides, like a man running for a train with a heavy suitcase in each hand, or an authentic Irish dancer doing his stuff,” wrote New York World-Telegram columnist Murray Robinson in 1954. “If you see any middle-aged Brooklynites gallumping for a bus with arms held straight down, you can bet they were Hi Myers fans in their youth.” Yet the genial Ohio farmer drew little national attention in his playing days and today his name is lost in the crowd of career .280-hitting outfielders of the Deadball Era. “He does his full share of spectacular stunts, is a good hitter and has an active, energetic manner that should attract attention to him,” wrote a Brooklyn reporter in 1917, “but it is a fact that he is seldom mentioned in the winter stories or the rainy day dope.”

Effective as a leadoff man or in the middle of the lineup, Hy (or “Hi”) Myers was a speedy center fielder whose unique running style made him popular with fans wherever he played. “Myers galloped with his long arms held straight down by his sides, like a man running for a train with a heavy suitcase in each hand, or an authentic Irish dancer doing his stuff,” wrote New York World-Telegram columnist Murray Robinson in 1954. “If you see any middle-aged Brooklynites gallumping for a bus with arms held straight down, you can bet they were Hi Myers fans in their youth.” Yet the genial Ohio farmer drew little national attention in his playing days and today his name is lost in the crowd of career .280-hitting outfielders of the Deadball Era. “He does his full share of spectacular stunts, is a good hitter and has an active, energetic manner that should attract attention to him,” wrote a Brooklyn reporter in 1917, “but it is a fact that he is seldom mentioned in the winter stories or the rainy day dope.”

Born in East Liverpool, Ohio, on April 27, 1889, Henry Harrison Myers broke in with Connellsville in the West Virginia-Pennsylvania League in 1909. On the strength of a .304 batting average, he was sold to Brooklyn on August 2 for a reported $300. He finished the season with the Superbas, appearing in six games and collecting five hits. But Myers was too green to suit Brooklyn boss Charlie Ebbets and manager Harry Lumley. One thing that made them wince was his habit of tagging up on any ball hit while he was on base, whether he had to or not. One day he was leading off second when the batter hit a long double. Myers could have scored easily, but by the time he went back to touch second, then headed home, he was out at the plate.

For the next four years the Superbas shuttled him around the minors. In 1910 they optioned him to Rochester; three weeks later he was on his way to the Sioux City Packers. The Packers fans loved his speed and all-out hustle in the field and on the bases, and didn’t care if he had trouble tracking fly balls. Myers batted .345, stole 33 bases, and hit an impressive nine home runs as the Packers won 108 games and the Western League pennant. The next spring Brooklyn optioned him to Toronto, which bounced him back to Brooklyn by way of two other stops. In his September recall, Myers got into 13 games but still didn’t impress Ebbets or new manager Bill Dahlen. Back he went to Sioux City in 1912, where the fans were overjoyed to see him. He batted .336 and stole 41 bases. The Superbas recalled him on August 20 but didn’t give him any playing time. Then they shipped him to Newark of the International League, where he played all of 1913 and half of 1914.

By that point Brooklyn had yet another manager, Wilbert Robinson. Uncle Robbie liked what he saw in Myers, despite a weakness for judging and getting a jump on fly balls. It took Myers all of 1915 to gain some mastery of that art, but for the next eight years he was Uncle Robbie’s center fielder. What most endeared Myers to Robinson was his hustle and alertness. Occasionally, with a man on second, Myers would sneak in to take a throw from the catcher and try to catch the unwary base runner; he earned at least one putout that way in 1916. In another game that year, Robinson recalled, the ball was being thrown “all over creation, and three or four men were running at once. When the big play came at the plate, whoever had the ball fired it to the man at the pan, and when the dust had settled, the Superbas were as much astonished as the newspaper men to find that Hi had taken care of the pan.”

Brooklyn won the 1916 pennant but lost the World’s Series to the Red Sox. In Game Two, Myers hit an inside-the-park home run in the first inning off Boston lefty Babe Ruth. The Red Sox tied it in the third, and with the game still tied in the last of the ninth, Boston had men on first and third with no outs. A fly ball was hit to Myers, whose throw to the plate got Hal Janvrin trying to score from third. The double play postponed Boston’s 2-1 victory and prolonged the game to 14 innings.

After the 1916 season, Myers went home to his farm near Kensington, Ohio. It wasn’t much of a farm: a horse and a few chickens. He thought he had earned a substantial raise for the next season and decided to bluff Charlie Ebbets. According to sportswriter Frank Graham, Myers had a letterhead printed, “MYERS’S STOCK FARM,” and wrote the following letter:

“Dear Mr. Ebbets:

“I am returning my contract unsigned. At the terms you offer me, I cannot possibly afford to play baseball any more. As you will see from this letterhead, I am now running a stock farm and I am doing so well that, in justice to my family, I must remain here. I have enjoyed playing in Brooklyn and will miss you and all the boys and the fans. Please remember me to the boys.”

Ebbets had a group of holdouts to contend with that season. He decided that visiting them at their homes might be the best way to talk them into signing. When Myers learned that Ebbets was on his way, he quickly made the rounds of his more prosperous neighbors’ farms and borrowed enough cattle and horses to fill his pastures. Ebbets took one look at the spread and gave Myers what he wanted.

SABR member Tom Knight has written that Myers waited a while before returning the borrowed livestock in case Ebbets came back. Then he hosted a barn dance for his generous neighbors.

Myers’ best years at the plate were 1919 and 1920; he led the league in triples both years, and in slugging average at .436 and RBI with 73 in the 140-game postwar 1919 season. Brooklyn won another pennant in 1920 and Myers led the team with 80 RBI. He had two hits in Game Five of the World’s Series against Cleveland but was not involved in the unassisted triple play made by Indians second baseman Bill Wambsganss. “I was sitting in the dugout at the time,” Myers recalled in a 1962 interview. “I can remember the play very vividly. There was a big hush over the fans. The crowd was stunned. Our players just stood there. No one left the field. It seemed like minutes before anyone realized what had happened.”

In the winter of 1923, Cardinals manager Branch Rickey needed an outfielder and had a good first baseman, Jack Fournier, to trade. According to contemporary accounts, Robinson gave Rickey a choice: Hy Myers or Zack Wheat. Myers would soon be 34, Wheat 35. Rickey chose Myers. “Give Rickey Credit For This Good Deal” headlined the hometown Sporting News. Myers hit .300 in 96 games, .210 in limited service in 1924, and retired after appearing in five games in 1925. (Wheat batted .375 each of the next two years and was still hitting above .300 in 1927.)

Myers went back to his farm in Kensington. He ran an automobile agency, then worked as a guard in a steel mill, later as a cashier at the Kensington State Bank. In 1958 he moved to the nearby town of Minerva where he suffered a fatal heart attack on May 1, 1965. He was survived by his wife of 53 years, Elsie Kibler Myers, one son, two grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

Note: A different version of this biography appeared in Tom Simon, ed., Deadball Stars of the National League (Washington, D.C.: Brassey’s, Inc., 2004).

Sources

The primary sources for this work include many contemporary newspapers. Also of assistance was a taped interview with Myers by oral historian Eugene Murdock.

Full Name

Henry Harrison Myers

Born

April 27, 1889 at East Liverpool, OH (USA)

Died

May 1, 1965 at Minerva, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.