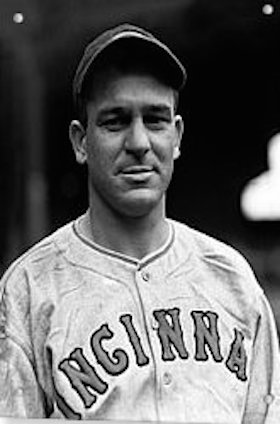

Dusty Cooke

Dusty Cooke’s father fought in the Confederate Army at Chancellorsville, which may partially explain why Cooke himself joined with the Phillies’ Ben Chapman in some of the most vicious racist taunting of Jackie Robinson in April 1947. Cooke was first-base coach for the Phillies at the time. He had also been a good ballplayer, though one who never lived up to what had appeared to be his potential.

Dusty Cooke’s father fought in the Confederate Army at Chancellorsville, which may partially explain why Cooke himself joined with the Phillies’ Ben Chapman in some of the most vicious racist taunting of Jackie Robinson in April 1947. Cooke was first-base coach for the Phillies at the time. He had also been a good ballplayer, though one who never lived up to what had appeared to be his potential.

The Cooke patriarch was E. Monroe Cooke (1843-1908), who had served with Company E, 13th North Carolina Regiment, CSA, and was wounded at Chancellorsville on May 3, 1863. He had enlisted in May 1861 and was promoted to second lieutenant in January 1865. After the war he returned to the family farm, though he was working as a dry-goods merchant at the time of the 1870 census. He raised, in a sense, three families: he had two children by his first wife, Victoria Boyd, four by his second wife, Cecilia Edwards, and four by his third wife, Nancy Anne Edwards, whom he had married 13 months after Cecilia’s death. Allen Lindsey Cooke was the fourth of “Nannie’s” children, born in Swepsonville, North Carolina, on June 23, 1907. His father died when he was just 18 months old.

The farm was on Swepsonville Road, in Graham Township.

Allen attended Durham High School in Durham, North Carolina, and grew to be a large man by the standards of the day – he is listed as 6-feet-1 and 205pounds. He may not have completed his studies; he told Henry P. Edwards that the principal had warned him he’d have to cut out either baseball or football and focus on his books. “I sorta agreed with the principal. I remembered the old saying, ‘If business interferes with your pleasure, cut out business,’ so I quit school and concentrated on baseball, which I figured would be combining business with pleasure if I made good.”1 The story probably got more attention than most educators would hope; the Greensboro Daily News later dubbed Cooke “the boy who wouldn’t stay in school.”2

Teammate Bill Werber wrote of Cooke, “You will not find his name in the Baseball Hall of Fame and present-day sportswriters have probably never heard of him, but he was denied baseball immortality by a quirk of fate.”3 The quirk of fate was a severe shoulder separation he suffered while playing for the New York Yankees in April 1931.

First, though, Cooke had put in some time in the minors. He’d played sandlot ball, of course, originally at third base but then shifting to the outfield because of his ability to chase down fly balls. And he played for some of the mill teams in the area.4 It was the veteran Possum Whitted who recommended him to the Durham Bulls in 1927. Cooke played outfield in 113 games, hitting .319 and leading the league in stolen bases with 33, and began to build a reputation.5 Whitted became manager of the Bulls partway through the Piedmont League season and the Bulls finished in last place.

Just a month into the 1927 season, New York Yankees scout Paul Krichell got a telegram from GM Ed Barrow telling him to head to Durham and check out Cooke. He was immediately won over by the strapping right-handed-throwing, left-handed-batting Cooke. Krichell later said, “When I saw him, I knew he was the ballplayer I had been dreaming about. He had everything. A big guy and strong … and he could run like a deer. He could hit and throw and he could go and get the ball in the outfield.” He offered Durham $2,500 for Cooke, quite a sizable sum at the time. Durham’s president Booker wired all the other big-league clubs asking them to make him an offer. Soon enough, Krichell said, “I found more scouts that I ever saw in one spot before. It was a scouts’ convention. Everybody was trying to outmaneuver the rest and get his bid in first and make it stick, because they were all like me: They needed just one good look at the kid. …” There was maneuvering aplenty and Krichell heard that another club had offered $10,000 and gotten a near-handshake agreement, but there was no paperwork yet. Krichell went to Booker’s house at 6 A.M. with his checkbook, and pulled out his pen and said he’d offer $15,000 – a very large sum then. “Make out the check,” said Booker, and Krichell had scooped the other scouts.6

Cooke joined the Yankees and manager Miller Huggins in St. Petersburg for spring training in 1928. On March 22 he was placed on option with the Asheville Tourists in the Class-B South Atlantic League; the New York Evening World said he’d had “greenness written all over him.”7 With Asheville, Cooke got experience; he appeared in 146 games, hammering out 13 homers and hitting for a .362 batting average, just four points behind the league leader. Asheville won the pennant, 18 games ahead of second-place Macon. Cooke hit 30 triples, indicative of his speed, and led the league. He was named to the league’s all-star team.

Promoted to Double-A, Cooke played for the American Association’s St. Paul Saints in 1929, winning the league’s Triple Crown, this time batting a nearly-identical .358 and leading the league with 33 homers and 148 runs batted in. Ben Chapman had played with him both in Asheville and St. Paul. Cooke was again an all-star. And ready for the major leagues.

At the winter meetings, new Yankees manager Bob Shawkey was looking ahead to 1930 and was high on Cooke. “He hits on six cylinders. I think he will take the place of Bob Meusel.”8 This was high praise indeed, to have the Yankees’ skipper already foreseeing him in the outfield alongside Babe Ruth and Earle Combs. The Associated Press saw Cooke as a “sure-shot.”9

He’d already earned the nickname Dusty due to his “trademark slides” into second base. His nephew John H. Smith later explained, “You get that kind of speed with that kind of size and you’re going to have a lot of dust.”10

Bubbles Hargrave, the manager of the St. Paul club, said, “This Cooke we are sending to Bob Shawkey is the best batting prospect to come up from our league in years. … Cooke is a game breaker, a pitcher wrecker. He has the knack of making his long hits when they are needed the most.”11 The New York writers were impressed with his build; John Kieran of the New York Times wrote, “He has shoulders as big as an icebox.”12 Bill Werber told of the time Cooke had gotten fed up with Babe Ruth’s needling during a game of bridge on board the train, and picked Ruth up and stuffed him into an upper berth. “No one got a bigger kick out of the manhandling than Babe himself.”13

Shawkey reported that he’d be starting both Cooke and Ben Chapman on Opening Day.14 Cooke had made the team despite struggling at the plate early on in spring training. A dispatch from Charlotte as the team prepared to play its final game of the exhibition season reported him batting .467 in the prior seven games, with 10 RBIs, taking advantage of his speed with a number of bunts and drag hits in the mix.15 Shawkey expected Cooke to take a little longer than Chapman to adjust to major-league pitching, but saw them both as naturals. It took Cooke a while to get his first base hit. Playing right field initially, he’d accumulated more than 23 plate appearances without a hit until a May 18 game against the Red Sox in Boston. Finally, a single got him on the board. A 3-for-4 day in Philadelphia, with two doubles, put him over .100. He got in a fair amount of work, appearing in 92 games as New York’s fourth or fifth outfielder, at all three outfield positions, and – thanks to Shawkey’s patience – raised his rookie batting average to .255 by the end of the season, with 6 homers and 29 RBIs.16 As a pinch-runner, he’d scored from first on Tony Lazzeri’s single on August 9 and his 11th-inning three-run Yankee Stadium homer on August 24 brought New York a 5-3 win over the Indians. In contrast, Chapman hit .316 with 81 RBIs in 138 games as the Yankees finished in third place.

The Yankees had a new manager in 1931 – Joe McCarthy. Sam Byrd and Cooke competed for the left-field job, and Cooke won out. He got off to a great start; four of his first eight games were multi-hit games. He was hitting .353 when misfortune struck. He’d been moved from left field to take over for the injured Babe Ruth in right and on April 26 suffered his own injury, falling hard on his right shoulder while diving for an Ossie Bluege drive. He had “displaced the outer end of his right collarbone and several ligaments were torn, but an x-ray showed no bones were broken.”17 It was thought he’d be out two weeks.

It took a lot longer than that. Cooke’s next appearance was as a pinch-runner, on June 28. In fact, the only work he saw for the rest of the season was as a pinch-runner other than two pinch-hit attempts, one in early August and the other in late September, both of which resulted in strikeouts. On September 27, the last game of the season, Cooke played left field and was 1-for-3, providing a little hope looking ahead. He’d put in some time playing in 30 games for Newark, working to rehab and to regain his bearings, and hit .284, though with only one extra-base hit.

Cooke later blamed a chaw of tobacco from the day before for the injury. “In my excitement to grab a long drive one day I swallowed my chew and was still so dizzy the following afternoon that in coming in for a drooping liner hit by Ossie Bleuge I stumbled, fell and broke my collarbone.”18 Because Joe McCarthy pulled Ben Chapman off second base and made an outfielder out of him –from that point forward Cooke took credit for Chapman’s career as an outfielder.

In 1932 Cooke only had one plate appearance in professional baseball. On May 28 he walked, and scored a run. He’d reported to New York City in early January for a thorough examination of his still-subpar shoulder. The Yankees were out of options, ruled Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, so Cooke had to be kept with New York or released outright.19 It was found he had a previously undetected splintered bone, which was removed in an operation.20 Things were looking up until an exhibition game at Cumberland when Cooke hurt himself again, throwing batting practice. When he hadn’t seen any action for more than a month. John Kieran commented on “the Forgotten Man” (Cooke) sitting in the stands with a melancholy air watching the other Yankees work out. Playing on Cooke’s Southern accent, Kieran said that Cooke declared himself on the “voluntarily retard” list.21 The Yankees swept the Cubs in the World Series, and generously voted Cooke a half-share in the proceeds.

Because Cooke had been sent home with full pay for the 1932 season, the rules permitted the Yankees to farm him out in 1933 rather than need to release him.22 He was optioned to Newark in January (though he trained with the Yankees and looked to have made the team, only to be released back to Newark just before Opening Day). He had a hard time getting going when the International League season began; after the first 19 games, he was batting just .203. But on May 15, Cooke got a break – if one calls being traded from a first-place team (the Yankees organization) to a last-place team, the Boston Red Sox, who had almost perennially been in last place for a decade. On May 15 he was traded to the Red Sox for Marv Olson, Johnny Watwood, and cash. It was one of the first deals made by new GM Eddie Collins, under new team owner Tom Yawkey. It seemed like a lot to pay to acquire an unproven, struggling outfielder, but Bill Werber (now on the Red Sox), George Pipgras, and others put in a good word for him.23 Cooke acquitted himself well. He played in 119 games for Boston and batted .293, with 86 runs scored and 54 RBIs. Perhaps none of the runs batted in were more satisfying than the four he knocked in on June 13, beating the Yankees, 6-5. His two-run homer in the seventh was the game-winner. Manager Marty McManus admired Cooke’s spirit and called him a “fighting, daring lad who is getting better.”24

In November 1933 Cooke had a minor operation on his right elbow. Good things were expected of him, and the Red Sox, in 1934. As it happened, however, he became a utility outfielder once more, got into fewer than half the games (74), and hit .244 with 26 RBIs. Carl Reynolds, Moose Solters, and Roy Johnson formed a better offensive trio in the outfield, collectively hitting well over .300. GM Collins said he’d been disappointed in Cooke in the utility role but agreed, “He has had more than his share of accidents.”25 Though Cooke played for several years, he never regained the power that had led some to foresee him as Babe Ruth’s understudy and successor.

According to Bill Werber, who roomed with Cooke for four years with the Red Sox, he would occasionally get depressed about the effect of his injury on his playing ability and quietly nurse a bottle of Jack Daniel’s. The result was that Cooke would inevitably pass out and fall out of bed. Werber couldn’t lift Cooke and so would cover him with blankets and let him sleep on the floor. The next day Cooke would be his normal outgoing self with no mention of the previous evening.26

Cooke was also known for his quick wit. Jimmie Foxx, his teammate with the Red Sox, often slugged tape-measure home runs. Once when Foxx hit a ball in League Park in Cleveland through the top of a white oak tree which was over the left-field bleachers and over a Lux Soap ad on top of the bleachers, Cooke looked over at Werber and said, “It’s a damn lie.”27 Later, when he was a coach for the Phillies, Cooke watched catcher Andy Seminick cold-cock Gene Hermanski of the Brooklyn Dodgers after Hermanski went out of his way to knock Seminick sprawling as he crossed the plate. Seminick was known as a tough guy whom one didn’t want to mess with. As the Dodgers helped Hermanski back to the dugout, everyone in the ballpark could hear Cooke yelling, “Okay. Who’s next?”28

Incoming 1935 manager Joe Cronin selected Cooke to play center field for the Red Sox in 1935, though he split his time mostly between center and right, and pinch-hit a fair amount, too. He came through with a .306 batting average in 100 games and a .400 on-base percentage, with 34 RBIs. Reynolds and Solters saw much less playing time. The Red Sox had become a first-division club, finishing fourth in both 1934 and 1935. Tom Yawkey’s investments had produced a better ballclub.

In December, there was an unfortunate incident in Durham when Cooke struck a boy on a bicycle, described as “Henry Griffin, 18-years-old Negro.” Griffin suffered a compound fracture of his leg. Cooke put him in the back seat of his automobile and then “left him on the steps” of the hospital. He was, in his own words, in “quite a bit of a hurry.” He was later arrested for assault and battery with a deadly weapon.29 On January 25, 1936, his car and another sideswiped each other in Lexington, North Carolina, and three people, including Cooke, were rendered unconscious in the resulting accident. Both cars were reportedly owned by Cooke, and both were demolished. The newspaper article reporting the story (and him being charged with reckless driving) said that his 1936 Red Sox contract, “which he had in his pocket, was about the only thing undamaged, officers reported.”30

In February 1936 Cooke married Daphne Rouse of Fuquay Springs, North Carolina. He did not have a good spring training but had a decent season. Although hampered by a knee injury, he played in 111 games and batted .273 (.401 on-base percentage), with 47 runs batted in. In December he was optioned to the Minneapolis Millers as part of a deal to acquire Fabian Gaffke. He had an excellent 1937 season in the American Association, playing in 151 games and batting .345 with 18 homers.

Near the end of the season, on August 20, the Cincinnati Reds bought Cooke’s contract. He had only turned 30 a couple of months earlier. Meant to report after the minor-league season was over, he didn’t play for Cincinnati until 1938. His work for the Reds was consistent with that for the Red Sox two years earlier – .275 in 82 games, with 33 RBIs. It was Cooke’s last year in the big leagues. In December he was traded to the Cardinals (with some cash) for outfielder Frenchy Bordagaray.

Cooke played the next four seasons in the minors. In 1939 he played for the Cardinals’ affiliate Rochester Red Wings and hit .340 in 147 games, though with only four home runs. He was with the New York Giants organization in 1940 and 1941, playing for Jersey City, but was back with the Red Wings (and the Cardinals) in 1942. His hitting ability declined distinctly each year – to .301, then .277, and lastly .232.

With World War II under way, Cooke enlisted in the US Navy in October 1942. This didn’t mean he couldn’t play baseball; in 1943, he played with the North Carolina-based Navy Pre-flight Cloudbusters, a team that also featured Ted Williams and Johnny Pesky from the Red Sox and several other major leaguers. Williams and Pesky were both aviation cadets at Chapel Hill at the time. Cooke worked as a pharmacist’s mate in the Navy, treating war-related injuries, but also gained experience in fitness conditioning. He did see combat and was involved in the invasion of Iwo Jima, when “his ship was under attack for more than three hours by Japanese suicide planes.”31

After his November 1945 discharge, Cooke was hired as the team trainer for the Philadelphia Phillies, beginning in 1946, working alongside manager Ben Chapman. Fiery as ever, an inning after Chapman was ejected from the August 16 game in Brooklyn, Cooke, too, was tossed.32 It was the following year, 1947, that he and Chapman were so hostile to rookie Jackie Robinson. It wasn’t just Robinson the Phillies harassed in 1947. They heckled everyone, and tartly, too. Their bench was “the most vitriolic in the league” and they got on Enos Slaughter, too. Cooke was said to be “one of the best jockeys … the trainer with the big voice.”33

That doesn’t mean it was innocent taunting. Philadelphia Inquirer writer Frank Fitzpatrick wrote, years later, “Those Phillies teams of the late 1940s and early ’50s had a Southern-born coach named Dusty Cooke, who used to ride Newcombe, Robinson, and Campanella particularly hard.”34

Unfortunately, Cooke seemed willing to go beyond just racial taunting. Johnny Blatnik, who was with the Phillies in 1948, remembered a play in which he laid down a sacrifice bunt and was out by about three steps at first as Jackie Robinson came over from second base to take the throw. Robinson’s foot was directly across the bag when Blatnik reached it, so he just jumped over the bag and didn’t even touch it. When he got back to the dugout, Cooke jumped all over him, saying, “You could have cut his Achilles tendon and then we wouldn’t have to put up with him anymore.”35

Cooke’s loud voice, whether hurling racial epithets or not, was legendary. According to Robin Roberts, it was the loudest voice in baseball. Roberts was known for his concentration on the mound and his ability to block out crowd and player noise, but Cooke’s voice was one he couldn’t block out. Late in life he still recalled Cooke yelling out to him on the mound in a tight spot, “Reach back and get it, Robbie, reach back and get it.”36

From 1948 through 1952, Cooke was the first-base coach for the Phillies and even the interim manager for a dozen games after Chapman was fired during the 1948 season; he was 6-6 over those games. Cooke finally got his chance to see postseason play, after having to sit out his time when with the Yankees back in 1932. He helped manager Eddie Sawyer coach the 1950 “Whiz Kids” to the National League pennant, though he saw them swept in the World Series by the Yankees. In December 1950 he suffered another serious automobile accident in front of his home in Fuquay Springs.

When Steve O’Neill took the managerial reins during the 1952 campaign, he kept Cooke on as a coach through the end of the year, but did not ask him to return.

Cooke became co-owner of Mobley’s Art Center, an art-supply house in Raleigh. Bill Werber described it as “a novelty shop full of glassware and bric-a-brac.”37 His obituary in The Sporting News said that in 1968 he had “suffered a stroke that left him unable to speak or write. But he had a rubber stamp made up, and used it to fill the autograph requests he received.”38

After suffering another stroke, Cooke died in Raleigh on November 21, 1987.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author accessed Cooke’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks to Paul Rogers for several suggestions.

Notes

1 Unattributed 1934 newspaper clipping found in Cooke’s player file at the Hall of Fame.

2 Greensboro Daily News, February 4, 1930.

3 Bill Werber and C. Paul Rogers III, Memories of A Ballplayer (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 2001), 21.

4 New York World, December 23, 1929.

5 The Oregonian (Portland), March 20, 1928, 21.

6 Krichell’s account is told in detail in Frank Graham, “Graham’s Corner,” New York Journal American, January 19, 1946.

7 New York Evening World, April 18, 1930.

8 San Diego Union, December 15, 1929. The October 24 New York Times had already declared Cooke “the outstanding candidate” to take Meusel’s berth.

9 See, for instance, the Hartford Courant, March 9, 1930.

10 Newark Star-Ledger, November 25, 1987.

11 New York World, December 23, 1929.

12 New York Times, March 11, 1930.

13 Werber and Rogers, 20. The Babe might not have been as amused had he read that Cooke had been wearing his uniform, with the number 3 on it, during the first day of spring training while Ruth was still a holdout. See the Greensboro Record, February 25, 1930.

14 Washington Post, March 27, 1930.

15 New York Telegram, April 11, 1930.

16 Fellow outfielder Sam Byrd appeared in the same number of games as Cooke, and hit .284.

17 Chicago Tribune, April 27, 1931.

18 Boston Globe, January 8, 1934.

19 New York Times, January 6, 1932.

20 New York Times, January 10, 1932.

21 New York Times, July 9, 1932.

22 Springfield Republican, December 18, 1932.

23 Boston Herald, May 16, 1933. The same day’s Boston Globe reported the cash as “probably $50,000 or more.” The October 27, 1934, Springfield Republican said it was $30,000.

24 Springfield Republican, August 2, 1933.

25 Boston Herald, December 21, 1934.

26 Werber and Rogers, 22.

27 Ibid., 75.

28 Robin Roberts and C. Paul Rogers III, The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996), 254.

29 Hartford Courant, December 10, 1935.

30 Greensboro Daily News, January 26, 1936. There is the possibility alcohol was involved in both driving incidents; Bill Werber’s book told of Cooke having “infrequent bouts” with depression and seeking solace in Jack Daniel’s. See Werber and Rogers, 22. The charges were dropped in the Griffin case in March 1936, with the payment of $700. See Boston Herald, March 4, 1936.

31 Philadelphia Inquirer, November 25, 1987.

32 New Orleans Times-Picayune, August 17, 1946.

33 The Sporting News of June 4, 1947, devoted more than a full page to the team and its practice of bench jockeying, replete with many of the jibes they used against various opponents.

34 Fitzpatrick continued, “One day, Newcombe, in retaliation, knocked down Ennis, the Phils’ cleanup hitter. Ennis picked himself up and shouted something into his own dugout. Years later, Newcombe asked Ennis what he had said. ‘I told that son of a [gun] to shut his mouth and leave you alone or I was gonna pull his tongue out,’ Newcombe recalled Ennis saying in a 2007 interview. ‘He didn’t have to go out there and hit against you.’” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 28, 2009.

35 Roberts and Rogers, 51-52. Amazingly, after the Phillies beat the Dodgers in 10 innings on the last day of the 1950 season to win the pennant, Robinson visited the Phillies clubhouse after the game and congratulated every player, even though Cooke and Ben Chapman were still Phillies coaches. Ibid., 52, 335.

36 Ibid, 131.

37 Werber and Rogers, 25.

38 The Sporting News, January 4, 1988.

Full Name

Allen Lindsey Cooke

Born

June 23, 1907 at Swepsonville, NC (USA)

Died

November 21, 1987 at Raleigh, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.