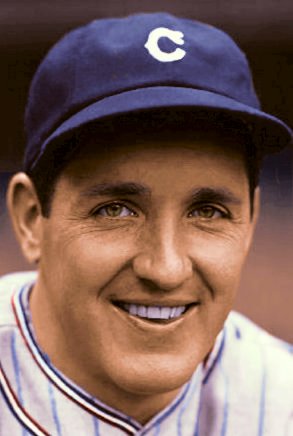

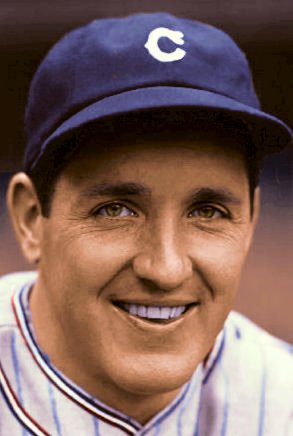

Billy Sullivan Jr.

Billy Sullivan played first base in high school and college. His reputation as a dead-pull, lefty hitter convinced the Chicago White Sox to sign him after the 1931 college season at Notre Dame and bring him directly to the big leagues. Sullivan arrived, a little in awe of his surroundings and thinking he might have a chance to get used to the new environment. To his surprise, manager Donie Bush started him immediately on June 9, in the totally unfamiliar position of right field. This was not the only surprise for Billy. With Lu Blue having a fine season at first base, Sullivan was moved across the diamond to third base.

Billy Sullivan played first base in high school and college. His reputation as a dead-pull, lefty hitter convinced the Chicago White Sox to sign him after the 1931 college season at Notre Dame and bring him directly to the big leagues. Sullivan arrived, a little in awe of his surroundings and thinking he might have a chance to get used to the new environment. To his surprise, manager Donie Bush started him immediately on June 9, in the totally unfamiliar position of right field. This was not the only surprise for Billy. With Lu Blue having a fine season at first base, Sullivan was moved across the diamond to third base.

Sullivan was born on October 23, 1910, in Chicago, Illinois. He was the youngest of two sons born to baseball catcher William Joseph Sullivan Sr. and his wife, Mary Josephine.i After his playing days, the elder Sullivan settled down to running the “Home Plate Orchard” near Portland, Oregon. Billy Jr. went to high school in Portland at a private prep school called Columbia. When he graduated in 1928 he had already finished a year of college credits. Billy had thought he would attend the University of California, but over the winter of 1927-28 his father met Knute Rockne. The youngest Sullivan headed to Notre Dame instead of Cal.

Despite the credits he had earned, Sullivan had to sit out the 1929 spring baseball season as an ineligible freshman. He played for the Fighting Irish in 1930 and1931. On campus he was a member of the Monogram Club, the Law Club, and found time to be chairman of the junior prom. He even had a job as secretary to the college president. Billy graduated in three years, earning a bachelor’s degree. He then returned to Notre Dame and earned his law degree in 1933. He never practiced law, but he left South Bend with a great education.

Billy’s father had given both sons advice about a life in baseball. He cautioned them both that life in the minors was not the way to go. If they chose baseball they should be sure they could get into the majors. Older brother Joe passed on a baseball career, but Billy had the talent to play. The elder Sullivan had also counseled Billy to ask for a $25,000 bonus and a two year contract. When the White Sox contacted him, Sullivan won the two-year contract at $1,000 a month. The Sox balked at the bonus and Billy settled for $10,000. Both figures were magnificent amounts for the Great Depression.ii

After that debut in right field, the Sox shifted Billy to third base. He played 83 games in 1931 and led the American League in errors. By his own admission, he could not get used to throwing the ball to first. However, he did get involved in two triple plays that first season. The most notable was on September 11, when he fielded a Babe Ruth grounder and started an around-the -horn triple play. At the plate he hit. 275 for a Sox club that was dead last in batting average and in the standings. The 1932 Sox were equally dismal, losing seven more games than in 1931. Lu Blue dropped off 70 points in batting and Billy found himself playing more first base than third. He led the team with a .316 average in 93 games. He was even tried behind the plate for a few games.

Ownership overhauled the Sox in 1933. A whole new outfield of Al Simmons, Mule Haas and Evar Swanson came to town. Jimmy Dykes was added as the new third baseman. Billy was targeted for first base along with Red Kress. Sullivan went into a horrible, season-long slump. He only played 54 games and hit a miserable .192.

During the previous offseasons, Sullivan had worked in retail in Chicago. He passed on the second job in 1933 to marry the former Louise Grant Barthman on October 9, at Notre Dame. Louise was from a well-to-do Chicago family and had attended St. Mary’s College, the women’s counterpart to what was then the all-male Notre Dame. The couple left on an extended honeymoon trip that took them to Oregon and then to San Francisco. In San Francisco they boarded the S.S. Lurline for a 90-day cruise of the Hawaiian Islands, Samoa, Fiji and Australia. Upon their return, the couple stayed in California and prepared for the late February opening of Sox spring training in Pasadena.

Sullivan’s first taste of spring training came in 1934. He had missed the previous two by permission because he was at Notre Dame finishing his law degree. The White Sox optioned Billy to Milwaukee at the end of camp. The Brewers installed Sullivan at third base and he enjoyed a resurgence at the plate, batting .343 and poking 17 homers for the third-place club. That fall the White Sox drafted outfielder George Washington in the Rule 5 draft, but the selection was overturned. Intent upon adding Washington to their lineup, the Sox sent Sullivan, $20,000 and another player to Indianapolis for Washington. Indianapolis then sent Billy on to the Cincinnati Reds. Once again with a last-place club, Sullivan served as the backup to Jim Bottomley at first base and Mark Koenig at third base. He was even pressed into action at second base for six games. The highlight of his season was playing third base in the first major league night game. As Sullivan recalled, “it was quite a night.”

In January 1936, the Cleveland Indians purchased Billy. Manager Steve O’Neill had the idea that Sullivan could be made into a catcher. Intense tutelage in the spring turned Sullivan into a serviceable backstop. The hard work did nothing to affect his hitting. He posted a .351 average, the highest average ever by any Indians catcher with 300 or more at-bats. He was even assigned to room with Bob Feller on the youngster’s first road trip and caught Feller in his first appearance.

Billy and Louise moved that winter to Sarasota, Florida. They stayed there the rest of their lives and raise their two daughters, Joan and Jill. Sullivan built their first home along with another carpenter. This experience led to the creation of the Sullivan Construction Company, which over the years designed and built scores of homes.

Sullivan saw considerably less action in 1937. Frank Pytlak handled the bulk of the catching. Billy pinch-hit almost as often as he caught. That winter he was involved in a trade that brought Rollie Hemsley to Cleveland from the St. Louis Browns. The rumor mill said Hemsley had barnstormed with Feller and that Rapid Robert had campaigned for a trade. Rollie had quite a reputation as partier and late-night carouser. Plain Dealer columnist James Doyle wrote a scathing article on February 12, 1938, praising Sullivan’s spirit and decrying Hemsley’s reputation.

The trade was fortuitous for Billy because he saw regular action in St. Louis. To his credit, Hemsley changed his lifestyle shortly after joining the Tribe. In 1938 Billy caught 99 games and hit .272. He led American League backstops with a .990 fielding percentage. In 1939 he served as a utilityman, the bulk of his action was in the outfield, and hit .289. That winter he was swapped for Slick Coffman of the Detroit Tigers. After two years with the cellar-dwelling Browns, Billy found himself as the backup to Birdie Tebbetts on the pennant-bound Tigers. Bobo Newsom was the ace of the pitching staff and notoriously superstitious. In St. Louis, Billy had been Bobo’s personal catcher. Reunited in Detroit, Bobo insisted Billy fill the same role. Sullivan also got the call as backstop when the Indians faced the Tigers late in the year and Detroit sent unknown Floyd Giebell to the mound. Sullivan recalls that they switched signs every inning because they felt someone was stealing the signs from the center-field scoreboard. Giebell tossed a shutout to secure the pennant for Detroit. The Tigers dropped the World Series to the Cincinnati Reds four games to three. Sullivan started three games, all starts by Newsom, and went 2-for-13. But his appearance in the Series made him part of the first father-son combo to have appeared in the Fall Classic; Billy Sr. played for the “Hitless Wonders” White Sox in the 1906 World Series against the crosstown Chicago Cubs.

In 1941, Sullivan enjoyed another year with the Tigers. He caught 63 games and hit .282. That winter he was sold to the Brooklyn Dodgers where he backed up Babe Phelps. Then World War II intervened and Sullivan joined the Navy. He was shipped from school to school and never was deployed. He earned the rank of lieutenant in the Naval Reserve. In 1945 and ’46 he had a series of government construction contracts. Released as a free agent by Brooklyn, Billy gave baseball one last shot when he signed with Pittsburgh for the 1947 season. He played his last game on September 3. At the close of the season he returned to his construction business and built modern homes in the Sarasota area.

Sullivan’s health failed in the winter of 1993 and he was hospitalized, ultimately being placed in a Sarasota nursing home. He died there of heart failure on January 4, 1994.

Sources

Cleveland Plain Dealer

South Bend Tribune

The Sporting News

A cordial thank you to Angela Kindig in the Notre Dame alumni office and to Carol Copley at the Notre Dame sports information office. They provided file information on Sullivan’s on-campus life and his wedding.

Eugene Murdock’s interview with Sullivan, housed at the Social Science section of the Cleveland Public Library.

Baseball-Reference.com

The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball.

Notes

i Details of Sullivan’s family and lineage can be found in the SABR BioProject account of his father, William Joseph Sullivan Sr.

ii These details came from the Eugene Murdock taped interview with Sullivan. It is available at the Cleveland Public Library and online at their digital database.

Full Name

William Joseph Sullivan

Born

October 23, 1910 at Chicago, IL (USA)

Died

January 4, 1994 at Sarasota, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.