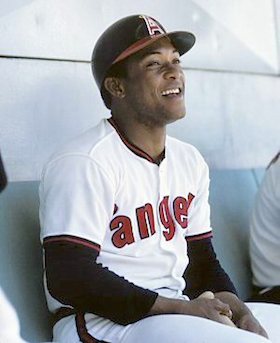

Sandy Alomar

A speedy, talented and versatile infielder, Sandy Alomar Sr. spent half a century in professional baseball as a player, coach, and manager. That time included 11 full seasons plus parts of four others in the majors from 1964 through 1978. Alomar made the American League All-Star team in 1970 and was a member of the New York Yankees when they reached the World Series in 1976. His biggest contribution to professional baseball, however, might have been his two very talented sons. Sandy Alomar Jr. played in 20 big-league seasons and was a six-time All-Star. Roberto Alomar was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2011.

A speedy, talented and versatile infielder, Sandy Alomar Sr. spent half a century in professional baseball as a player, coach, and manager. That time included 11 full seasons plus parts of four others in the majors from 1964 through 1978. Alomar made the American League All-Star team in 1970 and was a member of the New York Yankees when they reached the World Series in 1976. His biggest contribution to professional baseball, however, might have been his two very talented sons. Sandy Alomar Jr. played in 20 big-league seasons and was a six-time All-Star. Roberto Alomar was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2011.

Santos Alomar Conde was born in Salinas, Puerto Rico on October 19, 1943. His parents were Demetrio Alomar Palmieri, a sugar-mill machine operator, and Rosa Conde Santiago. There were eight children overall in the family.1 Small in stature at 5’9” and 140 to 155 pounds, Sandy was the only one of the family’s four ballplaying brothers to make it to the major leagues. Antonio (Tony) and Rafael got as high as Triple-A; Demetrio played Class C and D ball. All played in the Puerto Rican Winter League (PRWL).

The Alomar baseball heritage was also visible on the maternal side. Rosa’s cousin, Ceferino “Cefo” Conde, pitched 14 seasons in the PRWL, from 1938-39 through 1952-53. Infielder Ramón “Wito” Conde, Cefo’s son, played pro ball from the early 1950s through the early 1970s – including 14 games with the Chicago White Sox in 1962.

Santos starred for both Luis Muñoz Rivera High School in his hometown and for the local American Legion team. He signed as an amateur free agent with the Milwaukee Braves before the 1960 season, receiving a bonus of about $12,000. The scout was Luis Olmo, the second Puerto Rican to play in the majors. Olmo had seen Alomar ever since he was a youth in Little League and Pony ball.2 Sandy was just 16 when he signed at the same time with brother Demetrio, who was then 21. He was supposed to report to Eau Claire, Wisconsin in the Class C Northern League after the school year ended.3 As it developed, though, he did not play in the U.S. in 1960. He was on the restricted list (perhaps because of his age).4

Still only 17 in 1961, Alomar began his ride on the minor league whirlwind still familiar to young players. To his delight, when he landed in the Midwest League, he found himself teamed with Demetrio in the Davenport, Iowa infield. He later admitted that this fortuitous situation helped make his transition to American baseball more comfortable.5 He made stops in (among other places) Austin, Boise – where he hit a lofty .329 in 1962 – and Denver. Alomar began his PRWL career in the winter of 1961-62 with the Arecibo Lobos. He spent six seasons with the Wolves, followed by six with the Ponce Leones.

Alomar was called up from Milwaukee’s Triple-A Denver club in September 1964. He made his major league debut on September 15, a little over a month shy of his 21st birthday. He started at shortstop in the first game of a doubleheader at County Stadium and batted eighth, singling in a run in his first at-bat off St. Louis left-hander Ray Sadecki. A popup and groundout followed, before a pinch-hitter replaced him leading off the eighth. Besides batting 1-for-3, Alomar also made an error in the 11-6 loss. He started at short again in the second game, but had the misfortune of facing ace Bob Gibson, who struck Alomar out twice.

In 53 at-bats over 19 games in his first big-league stint, Alomar hit .245 with a double and 6 RBIs. He played the bulk of the following year for the Atlanta Crackers, which had become the Braves’ AAA team that season. He did appear in 67 more games for the big club, however, batting .241 with 8 RBIs while playing second base as well as shortstop. He also stole 12 bases.

The Braves’ major league franchise made its heralded move to Atlanta to start the 1966 season, but Alomar’s opportunities to make an impression were growing fewer. Spending most of that season in Richmond (the Braves’ new AAA home), Sandy – now playing mainly second base – got only 44 at-bats with the major league club, collecting merely a double and three singles for an .091 average. In 117 total games for the Braves over parts of three seasons, Alomar hit just .210 with four extra base hits, 16 runs batted in, and only 13 steals. He had made nine errors in the infield. Alomar’s days with the team that brought him to the United States were quickly coming to an end.

Before the 1967 season, the Braves sent Sandy to Houston as the player to be named later in a deal that had brought future Hall of Famer Eddie Mathews to the Astros. A month later, however, Houston moved him along to New York for utilityman Derrell Griffith. The Mets, entering only their sixth season as a major league franchise, were looking for a versatile infielder – shortstop Bud Harrelson was not yet ready and veteran second baseman Chuck Hiller was considered a weak glove man. “It was a case of trading a good bat for a good glove and speed,” explained Mets GM Bing Devine.6

Looking for a way to expand his value at the plate, Alomar came to camp determined to become a switch-hitter, something he had tried in his rookie season with the Braves with limited success. Unfortunately, the results didn’t change. He spent most of the year with the Mets’ International League team in Jacksonville, playing all four infield positions and the outfield but hitting only .209. When the Mets did recall him, Sandy got just 22 at-bats without a hit (this 0-for-22 streak stood for a time as a Met record for hitless futility.) And before the season was over, he was gone.

On August 15th, Alomar was once again a player named later. He was shipped to the White Sox to complete an earlier deal that had also sent third-base great Ken Boyer to Chicago. It was at this point that Alomar became disillusioned. “It was a nightmare,” he told a reporter in an interview three years later when asked about the season in which he was on the roster of four different major league teams. “Like a piece of garbage…They treat me like I was something they could throw away when they want to…They brainwash me. They tell me I cannot hit, that I good glove man…they say I am too little to not wear down. They make me believe these things myself…almost.” However, he had a backer in the White Sox organization: coach Grover Resinger, who knew him from his days with the Braves and from the minor leagues.7

When he had been sent back to the minors in June 1967, Alomar admitted he had thought of quitting and going back to Puerto Rico. “And then I look at my four mouths to feed and one on the way…and I think that for one last chance Sandy will go to the minors.”8 Santos Jr. had been born during the 1966 season while his dad was playing in Atlanta; Roberto was the “one on the way.” The first Alomar child was a daughter named Sandia. Sandy and María Angelita Velázquez had gotten married on December 23, 1963.9

In the Second City, however, Alomar’s prospects began to brighten. He appeared in only 12 games during the remainder of the 1967 season, but in 1968, Sox manager Eddie Stanky finally made Sandy a regular. Under the tutelage of scout and hitting instructor Deacon Jones, Alomar upped his average to .253, at one point in the season reaching .274. Infield mate Luis Aparicio was impressed: “That fellow has improved 150%,” remarked the future Hall of Famer.10

That winter, Ponce won the first of back to-back PRWL championships. Rocky Bridges, then a coach for the California Angels, managed the 1968-69 squad. Unfortunately, Alomar had a slow start to the ’69 big-league season. He was traded again, to the Angels on May 14th, in a package for infielder Bobby Knoop. Though Knoop was coming off three consecutive Gold Glove awards, the Angels thought Alomar could do everything except make the pivot as well as or better than Knoop.11

Angels’ manager Bill Rigney thought he saw in Alomar a chance to kick-start his lineup from the top. “We’ve never had a leadoff hitter,” said Rigney. “If we’re going to do it with singles, we might as well do it with speed, too.” Rocky Bridges was also excited: “Sandy can run,” he remarked. “He’ll create excitement. The fans will be looking for him to go every time he’s on first.”12

It was in Anaheim that Sandy Alomar finally settled down. Installed as the everyday second baseman, Alomar had almost 600 plate appearances in 1969, hitting a passable .250 with 30 RBIs, though he stole only 18 bases. With Ponce that winter, the Leones repeated as PRWL champs. The skipper was Alomar’s double-play partner with the Angels, Jim Fregosi, in his first job as manager.

If Angel fans were truly looking for Alomar to run every time he got on first, they felt much more confident in 1970. Playing the full 162-game schedule for the first time, Alomar hit .251 in 672 at-bats, driving in 36 runs and swiping 35 bases. He also walked 49 times with only 65 strikeouts, helping make him the leadoff hitter the Angels had been hoping for.

Alomar’s season was impressive enough for him to be named as an AL reserve in the All-Star Game after Rod Carew was injured. He took great pride in having his hard work recognized.13 At Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium, he went hitless in his one at-bat, flying out against Claude Osteen in the top of the 12th in what’s remembered as the “Pete Rose-Ray Fosse” game.

Alomar’s professional peak was the 1970-71 winter season. He hit a league-leading .343 in 251 at-bats for Ponce and was named the PRWL’s Most Valuable Player. The Leones finished in fourth among the league’s six teams that season, however, and were knocked out in the semi-finals.

The next season with the Angels proved to be Alomar’s most successful in the majors. Now 27 years old, he collected close to 700 at-bats for the second year in a row and hit a new high, batting .260. He also set personal career bests with 179 hits, 42 RBIs, and 39 stolen bases. In addition, he set a major-league record by coming to the plate 739 times without being hit by a pitch (Alomar was struck by a pitched ball only three times in 15 seasons).

Overall, Alomar enjoyed the most productive stretch of his career in Southern California – in a period covering four full seasons and parts of two others, Sandy appeared in close to 800 games, hitting .248 with 162 RBIs; he stole 139 bases in 186 attempts. At 30 years old, the veteran infielder felt he had finally made his mark. Alomar played in a remarkable 648 consecutive games in one stretch from 1969 through September 1973, until he suffered a broken leg when Jerry Hairston Sr. slammed into him while breaking up a double play. This streak – which earned Alomar the nickname “The Iron Pony” – is still 19th-longest in big-league history.

Alomar sat out the 1973-74 winter season in Puerto Rico while he recovered from his broken leg. Meanwhile, in December 1973, the Angels acquired second baseman Denny Doyle from the Philadelphia Phillies. Doyle won the starting job in California that spring, and in July 1974, after playing in just 54 games as a reserve, Alomar was on the move again. His contract was sold to the New York Yankees, who had parted ways with their second baseman since 1967, Horace Clarke, that May.

The change of scenery helped – Alomar batted .269 in 76 games while playing second base in the Bronx. When he came back for the 1974-75 season in Puerto Rico, he was a member of the Santurce Cangrejeros. He played in five seasons for the Crabbers.

The whole Yankee team got off to a slow start in the 1975 season. Sandy was hitting a meager .205 and even floundering in the field. He began to question himself. “When I’m in my room by myself, that’s when I think about the way I am going,” he mused. “I think, ‘Why do you do this when you could have done that? Why do you miss that pitch…why do you miss that ball?’…There are times when I ask myself whether I can hit or not.

“Sometimes I go to a restaurant and I order and I don’t feel like eating…I know, myself, that I’m a better hitter than what I’m doing now. A baseball player – you have to accept the ups and the downs.”14

Still, the Yankees, meandering to an 83-win, third-place finish in the AL East, kept Alomar in the lineup almost every day. He ended the season hitting .239 in 151 games with 28 steals. His .975 fielding percentage led all major leaguers at the keystone base.

In the Yankees’ pennant-winning year of 1976, Alomar, now a utilityman with the emergence of young second baseman Willie Randolph, did everything on the field except pitch and catch. He appeared in 67 games and mirrored his previous season, hitting .239.

More importantly, for the first time in his major league career, Alomar found himself in the post-season, as the Yankees won the AL East and then their first pennant since 1964. In the AL Championship Series against Kansas City, Sandy went 0-for-1 in his single plate appearance, flying out as a pinch-hitter to end New York’s 7-4 defeat in Game Four. He was also called on to pinch-run, but was caught stealing second base to end the sixth, in what ultimately turned out to be a Yankee win when Chris Chambliss homered in the bottom of the ninth to win the series. Alomar did not appear in the World Series in that or any other year.

His value as a utility player made him attractive to other teams, however, and the Texas Rangers traded for him in February 1977, in a deal that sent infielder Brian Doyle to the Bronx. Over parts of the next two seasons, Alomar continued in his role as utilityman, hitting .265, mostly as a DH. In 1978, his U.S. career came to a close; he got only 29 at-bats and collected only six hits. He was released by the Rangers at the end of the year.

The final numbers in the majors for Santos Alomar Sr. are not imposing. Over a 15-year major league career and over 4,700 at-bats, he hit just .245 with 13 homers, 282 RBIs, and 227 stolen bases (he was caught 80 times). His on-base percentage was a lowly .290, but his fielding percentage was a solid .976.

Alomar did not play in Puerto Rico in the winter of 1978-79 after the Rangers released him. However, he appeared for Santurce in 25 games in 1979-80. He closed out his playing career the following winter with six appearances as player-manager for Ponce. Overall, Alomar hit .270 in over 1,000 games in the PRWL during 18 seasons (the exact number of total games is not certain because the figure is missing for 1963-64). He hit 25 homers and stole 168 bases, leading the league in steals an unequaled six times.

But Sandy Alomar’s contribution to the game he loved would not end with his retirement. Back in Puerto Rico, he bought a gas station in Salinas, while his two sons learned the game their father had made his livelihood. While Sandy Jr. and Roberto honed their baseball skills, Sandy Sr. continued working in baseball, coaching the Puerto Rican national team from 1979-1984. In the 1980s, he coached and managed with Santurce and again with Ponce.

Roberto, who grew to 6 feet, and Sandy Jr., at 6-feet-5, were both much bigger than their father. When asked about the physical differences in 1997, Sandy Jr. remarked that his mother was relatively tall at 5-feet-7, while his uncles were all tall as well. “My father is the only midget,” he concluded.15

Luis Rosa, a San Diego Padres scout working throughout Latin America, came to see both Alomar offspring. He also approached their father about a position in the organization. The Padres’ director of minor league scouting was looking for an infield instructor and Alomar had played for San Diego manager Dick Williams when they were both with the Angels. Thus, the Padres hired him, but made it clear that it was not to encourage his talented sons to sign with their team.16 Eventually, however, they both did.

Their father claims he never pressured either of them to pursue a baseball career. Though Roberto always wanted to be a big-leaguer, Santos Jr. stopped playing ball for a couple of his teenage years to ride dirt bikes. “My dad gave me a speech,” Sandy Jr. said years later. “He said that riding bikes was a hobby and not a job … you spend money in that. You don’t get money.”17

The senior Alomar tried not to give his sons too much baseball advice either, but Sandy Jr. believed that being the son of a major-leaguer had its advantages and disadvantages. “You have a name that helps you,” he said. “But some people do expect you to be the same as your father. That’s not right. We’re different people.”18

As his progeny made their way through pro ball, their father’s coaching odyssey continued: He served as a coach for the Padres’ affiliate in Charleston, South Carolina in its inaugural season – both of his sons were on the team. Sandy Sr. then became a major-league coach for the Padres from 1986 through1990, so he was on hand when his sons reached The Show in 1988.

Sandy Sr. then joined the Chicago Cubs organization, working as a roving minor league instructor during the 1990s. He also managed their Williamsport team in the NY-Penn League for part of the 1994 season, as well as their Gulf Coast Rookie League team in 1995 and 1996.

Alomar joined the Cubs’ major league staff in 2000 and remained there for three seasons, as bullpen coach and (in 2002) as first-base coach. He then moved to the Colorado Rockies’ third-base coaching box for two seasons. Alomar remained connected to the Puerto Rican baseball scene too. He served as general manager of the San Juan Senadores in 1999-2000. He also managed the national team in regional tournaments in 2003.

Alomar returned to the Mets in 2005, serving as first-base coach for two seasons, third-base coach for two more, and then finally becoming bench coach. He actually managed a game on May 9, 2009, after Jerry Manuel was suspended for an altercation with umpire Bill Welke. When the Mets beat Pittsburgh 10-1 and the Phillies lost to the Braves, the Mets moved into first place in the NL East under Alomar’s one-game stewardship.

That season, however, was his last in a big-league uniform, though he managed again in the Gulf Coast Rookie League for the Mets in 2010.

In 2015 Sandy Alomar turned 72. The website Champions of Faith notes that Alomar is a lifelong Catholic and that he calls his wife María “the spiritual leader of the family”.19 They have six grandchildren to date.

In stature, Sandy Alomar Sr. was not a giant. But on the diamond, though he had his share of struggles in the game, his pride and perseverance made him a useful asset. His defensive versatility helped, as did an obvious passion to play as well as he was capable in every game. As Grover Resinger put it in 1970, Alomar had value “defensively, offensively and inspirationally.”20

In 2014, Alomar himself expressed it this way as he passed on lessons from his decades of wisdom at the Vauxhall Academy of Baseball in Canada. “Size really doesn’t matter if you have faith in yourself and you know you can do it. If you sacrifice, and you put the effort in, you will become what you feel it is you should become.” 21

He repeated a different dictum later that year at another baseball camp in Canada. “When you have pride, you have a will. When you have a will, you have respect. When you have respect, you create discipline. Discipline gives you knowledge. Knowledge gives you awareness. And awareness gives you anticipation.”22

This biography is included in “Puerto Rico and Baseball: 60 Biographies” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Edwin Fernández.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Rory Costello for his input.

Photo credit: National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Sources

Internet resources

Ancestry.com

Myheritage.com

Books

José A. Crescion Benítez, El Béisbol Profesional Boricua, San Juan, Puerto Rico: Aurora Comunicación Integral, Inc., 1997.

Newspaper articles

In addition to those cited in the notes, I also used several articles from the below.

Chicago Tribune

New York Times

Chicago Daily Defender

Notes

1 The names of six siblings are available: Luz María, Víctor Manuel, Guillermina, Antonio, Rafael, and Demetrio.

2 Thomas E. Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1995, 130-131.

3 “2 Brothers Sign Eau Claire Pacts”, Milwaukee Sentinel, January 29, 1960, Part 2: 5.

4 Sporting News Baseball Register, 1965.

5 Marc Appleman, “Like Father, Like Sons”, Los Angeles Times, March 5, 1985.

6 Joseph M. Sheehan, “Mets Get Alomar, Infielder, and Send Griffith to Astros”, New York Times, March 25, 1967.

7 John Wiebusch, “Alomar: Castoff Role a Nightmare”, Los Angeles Times, June 19, 1970.

8 Wiebusch, “Alomar: Castoff Role a Nightmare”

9 Bob Elliott, “Alomar Fulfilled Island’s Dream”, Toronto Sun, January 12, 2011. Sporting News Baseball Register, 1965.

10 “Sports Ledger”, Chicago Defender, September 3, 1968.

11 Wiebusch, “Alomar: Castoff Role a Nightmare”

12 Ross Newhan, “Angels Acquire Alomar, Priddy in Knoop Trade”, Los Angeles Times, May 15, 1970, Sports-1.

13 Dick Miller, “Alomar’s an Angry Angel, Raps His Rep as ‘Unknown’”, The Sporting News, April 10, 1971, 31.

14 Steve Jacobson, “Alomar Finds Solace of a Sort in Music”, Newsday, July 24, 1975.

15 George Vecsey, “The Alomars Meet Again in October”, New York Times, October 8, 1997.

16 Appleman, “Like Father, Like Sons”

17 Appleman, “Like Father, Like Sons”

18 Appleman, “Like Father, Like Sons”

19 www.championsoffaith.com/athletes/athlete_new.asp?athleteID=18

20 Wiebusch, “Alomar: Castoff Role a Nightmare”

21 “Baseball patriarch imparts wisdom”, Vauxhall (Alberta, Canada) Advance, March 7, 2014.

22 Mark Malone, “Alomar shares experience at Blue Jays camp”, Chatham (Ontario, Canada) Daily News, June 25, 2014.

Full Name

Santos Alomar Conde

Born

October 19, 1943 at Salinas, (P.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.