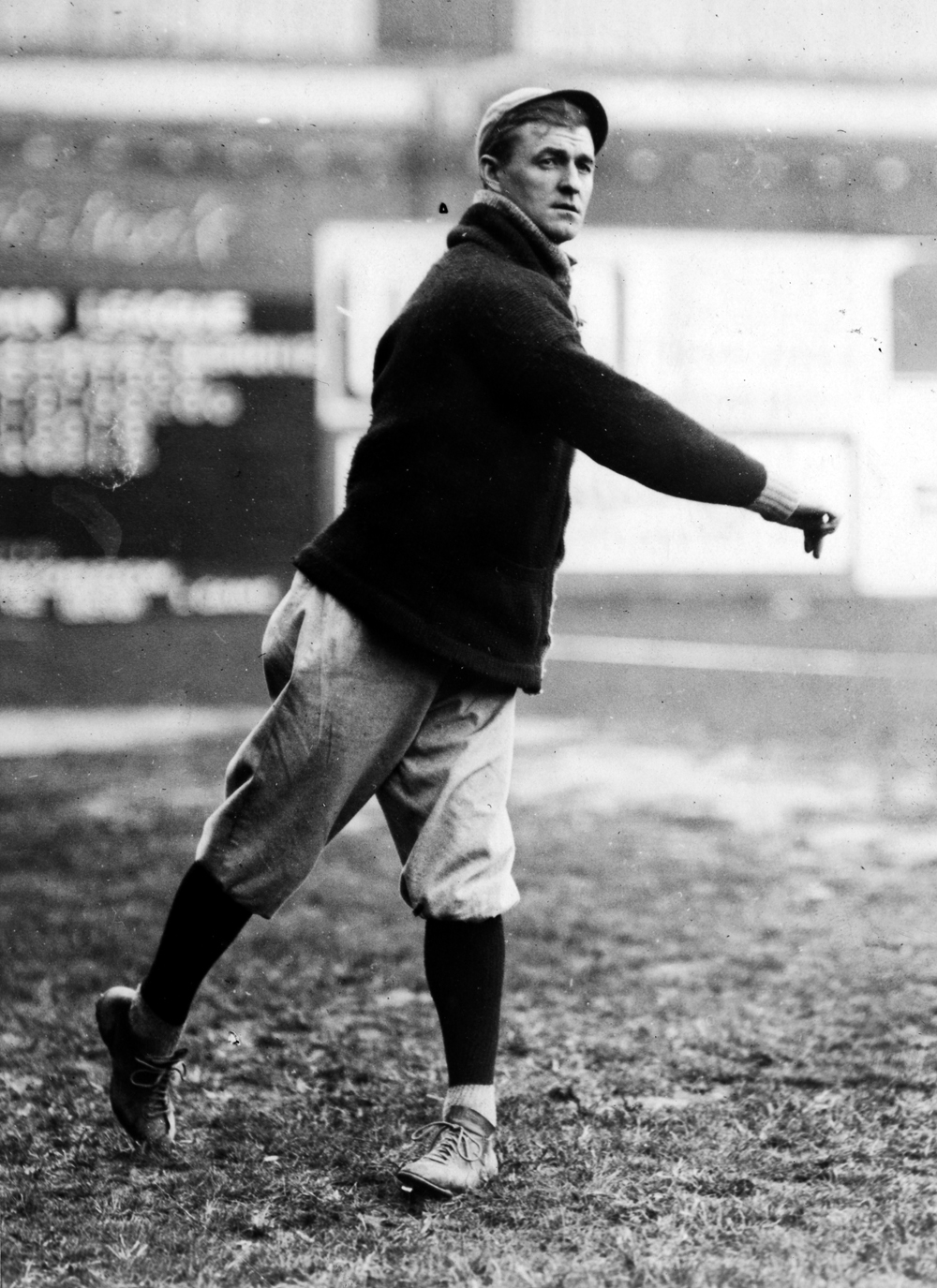

Buck O’Brien

Asked by a sportswriter in January 1912 which pitcher was giving him the most trouble in the American League, Ty Cobb did not mince words. “I believe I have never in my life faced a pitcher who bothered me so much as that man O’Brien,” he growled. “O’Brien has everything. He has a ‘spitter’ the like of which I have never seen before. It breaks like a shot and is absolutely impossible to gauge it with any degree of consistency.”i

Asked by a sportswriter in January 1912 which pitcher was giving him the most trouble in the American League, Ty Cobb did not mince words. “I believe I have never in my life faced a pitcher who bothered me so much as that man O’Brien,” he growled. “O’Brien has everything. He has a ‘spitter’ the like of which I have never seen before. It breaks like a shot and is absolutely impossible to gauge it with any degree of consistency.”i

The son of Irish immigrant John B. O’Brien and Margaret Willis, a native of nearby Braintree, Thomas Joseph O’Brien (known as Buck from an early age) was born in Brockton, Massachusetts, on May 9, 1882. The eldest of eight children (four boys and four girls), he grew up in a modest 2½-story home in the Bush, a working-class, overwhelmingly Irish Catholic neighborhood on the south side of town. Then a small but growing mill city of 27,000, Brockton fancied itself the Shoe Center of the World,ii and like most of the city’s working-class Irish, Buck’s father earned a livelihood assembling footwear at the benches of the Walkover Shoe Company. At one time or another, all the O’Brien children spent time at the benches at Walkover Shoes, and at least one, Buck’s younger sister, Hannah, spent a lifetime there.

As a boy, Tommy O’Brien attended St. Patrick’s, a parish school opened in 1887 by the Sisters of Charity of Nazareth. He was a gifted tenor and athlete, and his life revolved around his passion for theater and sports. Throughout middle and high school, he starred in a series of operas produced at St. Patrick’s, and each Sunday he was a regular soloist with the parish choir. “My father had a gorgeous voice, absolutely gorgeous,” recalled Buck’s daughter, Rosemarie O’Brien Moran. “He was a high tenor, and he was always singing around the house.”iii And after fulfilling his obligations at school and church, like many a young man in Brockton, his interest shifted to matters of sport.

John O’Brien made it a point to instruct all of his sons in the manly art of self-defense. Fiercely competitive and deeply athletic, Buck took to boxing even more naturally than baseball, and by his teens there wasn’t a young pugilist in town who wasn’t aware of his prowess in the ring. “Well, sure he was a boxer,” recalls Rose Moran, “but he was never a vicious man; in fact, he was really very quiet. He was not prone to fighting, but he was big and strong, and he fought when he had to.”iv

By his 17th birthday, Buck was making a name for himself singing locally and playing ball in the Brockton city league. In the summer of 1899 he held down first base for Brockton’s semipro West Enders, playing in front of wild hometown crowds against clubs in the greater Boston area. Two years later he joined Brockton’s Walkover Shoe factory team. Led by a longtime friend of his, pitcher Billy Reardon, the Walkovers were enormously popular among Brockton baseball rooters, who turned out in droves at the club’s Highland Park grounds.

It was during a contest against Holbrook early in 1904 that Buck’s baseball career began to shift from infield to the pitching mound. During an infield play when he made a putout at first, Buck rifled a shot across the diamond and picked off a runner racing for third. According to a story reported 40 years after the events, when the inning was over, the Walkover third baseman approached Buck at the bench.

“Buck, that was a honey of a throw. Did you know it was going to jump?”

“No, I didn’t,” answered Buck.

“Well, it did, old top, and if you can get it under control you can become a great pitcher.”v

Buck took the advice to heart, and that summer began throwing regularly. “Regarding O’Brien’s early plunge into baseball, the rumor still holds water that he gained the greater part of his excellent control by chucking fast ones at an African dodger at Nantasket Beach,” the Boston Post later reported, adding, “The mortality reports concerning the latter gentry bear out the rumor.”vi

A large measure of Buck’s newfound success on the mound was tied to his quick mastery of the trick pitches that, thanks largely to Big Ed Walsh’s success in Chicago, were garnering notoriety across baseball. By its very nature, the spitball was a difficult pitch to control, but Buck quickly developed a knack for it and demonstrated uncanny command. “Buck O’Brien was an enigma,” the Brockton Enterprise said when he led local factory players to a thrilling victory over a team from the Olneyville section of Providence, Rhode Island, over the July Fourth weekend in 1906.vii “He was as accurate as a die, not issuing a pass.” Buck was also proving no slouch at the plate, elevating his batting average over 60 points (from .222 to .286) during one hot stretch in August.viii

When the Walkovers failed to field a team for ‘07, O’Brien went to work elsewhere. He was hotly pursued by the Portland tam of the Maine State League but, already enjoying steady work as a solo vocalist with Brockton’s Gem Theater, he indicated his desire to stay close to home. When a semipro team in Wakefield, outside Boston, made him a “financially satisfactory” offer that obligated him to play but one game a week, he jumped at it.ix Buck’s strong work finally caught scouts’ eyes, and at the end of July he was tendered his first professional offer by the hometown Brockton Tigers of the New England League.

Led by the legendary Framingham brothers Mike and Marty O’Toole, the Tigers had been dogging Jesse Burkett’s Worcester Busters for most of the summer, and the Brockton Enterprise gushed forth local pride when the team announced that it had signed a “local youngster” to its roster.x Buck’s professional debut, on August 20, 1907, against Haverhill (Massachusetts) was well attended, but Buck was an utter wreck. After handing out six runs through the first four innings, he was benched by manager Stephen Flanagan. The Tigers rallied to win 9-7, but at least one local writer chided Buck for woeful control and “mutton” speed.xi

O’Brien fared far better in his second start, nine days later. Facing cellar-dwelling Lawrence, he started the contest poorly, accidentally whipping the ball into the grandstand in the first inning. He settled down and, with solid speed and control, “went through nine innings in swell shape, never once faltering” and walked off the mound with a 6-2 win.xii

Buck made one more appearance that summer, the end of his short-lived career with the New England League. With most of the Tigers lineup returning for 1908, Buck opted to accept another offer to travel to Paterson, New Jersey, to play for the outlaw Union League Intruders. A minor-league city best known for the remarkable baseball feats of its most distinguished alumnus, Honus Wagner, Paterson suffered from gross mismanagement and lax fan interest. Buck fared as poorly as his struggling franchise, limping to a 2-9 mark by late May. On May 21 he bolted from the team, which itself folded three days later.xiii Returning home, he pitched for Taunton, Massachusetts (Old Colony League), and grew stronger and more confident with each start. With the pennant on the line, on September 8 O’Brien won back-to-back complete games against Somerville, and then a 5-0 win over Rockland to help Taunton win the pennant.xiv

Buck’s 12 victories that summer caught the eye of a number of big-league scouts, among them Weymouth, Massachusetts, native and Indianapolis Indians catcher Howling Dan Howley. “I had heard about Buck from the boys around Goat Valley,” Howley recounted nearly 40 years later. “Brockton, not being far from Weymouth, I made a trip up there and didn’t have to use my best oratory to induce him to forget to report to the Walk-Over Shoe the following season.”xv

Indianapolis had O’Brien pitch for the Evansville (Indiana) River Rats (Class B Central League) in 1909. He started slowly, but grew stronger as the season progressed, winning eight straight games and 13 of his last 15 to close out the season at 18-11.

A month later a “tickled” O’Brien traveled with the Indianapolis team to Cuba for a barnstorming trip across the island.xvi Steady rains caused the postponement of most of the games, but on October 25, Buck took the mound and whipped an aggregation of Cuban ballplayers, 4-2.xvii Two weeks later he was back in Brockton for the winter.

Unexpectedly released in February 1910, Buck joined the Connecticut State League Hartford Senators, a powerhouse of a club that had taken the flag the previous year, but as was the case with Evansville a year earlier, his new franchise was a winner turned loser. Hartford took a nose dive out of the gate, eventually finishing the summer in fifth place. And yet again, Buck O’Brien stood out as one of the top hurlers in the league, notching 20 wins (against 10 losses) for the first time in his career.

Waterbury manager Mickey Finn got in touch with the New York Giants’ John McGraw in early August, but a scout McGraw sent reported, “The young feller didn’t show nothing.” McGraw passed.xviii Days later, on August 20, Buck’s contract was scooped up by John I. Taylor and the Boston Red Sox.

After an active offseason of stage performances in and around Brockton, Buck boarded the Red Sox express bound for 1911 spring training in Redondo Beach, California, and formed the Red Sox Quartet in the course of the cross-country trip. He showed poor form for the Red Sox rookies in a 4-2 exhibition loss to the Lynn Shoemakers on April 15, and was assigned to the Denver Grizzlies of the Class A Western League. When Buck settled in, he began turning out one dazzling performance after the next. On June 5 he pitched and won both ends of a doubleheader against Des Moines (13-3 and 14-1), and facing a pack of St. Joseph’s “hoodlums” three days later, he tied Marty O’Toole’s Western League strikeout record by fanning 18.xix

Buck marked Independence Day by tossing a no-hitter against Lincoln, 5-1 (Lincoln’s lone run coming on an error). By early September, he led the league in strikeouts with 261 (against 77 walks), and his 26-7 record ranked him second in games won, helping lead the Grizzlies to a 111-54 mark and the pennant.

Buck’s return to the Red Sox in September could not have come at a better time. Mired at .500 for most of the summer, the Sox had tanked badly, dropping seven straight games and 10 of their last 11. After three days on the rails, O’Brien met up with the team in Philadelphia on September 8. The next morning Boston manager Patsy Donovan approached Buck and asked if he was “ready for a crack at the reigning American League champs.”xx Buck had not touched a ball in five days, but he offered to loosen up and see how he felt.

The day was overcast and a light rain fell at Shibe Park. Buck took the ball, squaring off against Eddie Plank, and, given a 2-0 lead in the first inning, he never looked back. “Buck went about his business as if he were working against some bush league nine,” the Enterprise recorded. There was no faint heart, no falter, no flurry or even indecision.”xxi Philadelphia fans rocked the grandstand with the home team trailing 2-0 in the bottom of the ninth, but Buck coolly struck out Amos Strunk to secure the win and his first big-league victory.xxii

After the game manager Patsy Donovan broke into a broad smile, and remarked, “O’Brien is a corker.”xxiii

Winning five of six games to close out the final four weeks of the summer, Buck established himself as one of the game’s hottest properties. Umpire Silk O’Loughlin remarked during the offseason that O’Brien had “all kinds of nerve and confidence,” calling him “the upcoming star of the American league.”xxiv Detroit Tigers president Frank Navin went even further, stating, “He came in like Cy Young did, late in the season, and he made good in a way, in fact, that forecasts a career that may rival young. O’Brien is the man that will make Boston play like champions.”xxv

If the accolades Buck drew from baseball circles weren’t enough, there was also his budding stage career with the new Red Sox Quartet. “When he came forward to sing his solo, the crowd that filled the theater burst into applause that lasted several minutes,” the Brockton Enterprise recorded after a performance in Biddeford, Maine.

After a brief holdout, Buck signed a $4,200 deal with new Red Sox owner Jimmy McAleer in 1912 and joined his teammates for a song-filled train ride south. Buck nailed a home run over the fence for the rookies to open camp, and despite a series of delays through the rain-filled month of March, he and his teammates slowly ground themselves into shape. “I will bank on the prediction that Joe Wood and Buck O’Brien will pitch remarkable ball this year,” the Boston Globe’s Tim Murnane predicted as camp drew to a close.xxvi

Much to the delight of the growing legion of Red Sox rooters, after launching into the regular season with a convincing sweep of the lowly New York Americans, the 1912 Red Sox quickly found a pleasing formula to keep the peace: victory. Buck opened his season in fine fashion, tossing a 5-2 victory over Russ Ford on April 12.

On April 20 Buck was far from sharp in the first game the team ever played at brand-new Fenway Park. He yielded three runs in a sloppy opening frame. He labored again in the second, then was tagged twice again in the third, thanks in large measure to his own miscue – a bizarre balk that was called when the saliva-soaked ball accidentally slipped from his hand and rolled helplessly off the mound. Jake Stahl pinch-hit for O’Brien when the pitcher’s spot came up in the fourth; behind Charley “Sea Lion” Hall, the club rallied late to nail down a 7-6victory in 11 innings.

O’Brien’s rough outing in the home opener was followed by subpar performances over the next several weeks and was a major source of concern. It wasn’t until Memorial Day that he finally began to find his groove. He won five of his next six through the end of June, and made several outstanding relief appearances to raise his record to 12-9 by the first week of August. As eyes across baseball grew transfixed on Joe Wood’s staggering 34 victories, O’Brien quietly amassed a series of impressive outings in his own right, notching seven wins in eight starts to bring his record to 20-13 by the end of the season.

After seeing the pennant become theirs, the club returned from the road to a massive welcome and parade through the streets of downtown Boston. Hours later, Brockton treated its own hometown hero to a parade of their own.

Joe Wood opened the 1912 World Series against the New York Giants in New York’s Polo Grounds with a thrilling Game One victory. Game Two a tie called at dark, and on October 10 Buck took the mound at Fenway Park against Rube Marquard. In another hotly-fought pitchers’ duel, Buck threw well but was nicked for single runs in the second and fifth. Boston fought back in the ninth, but when Hick Cady lined out to deep right field leaving Heinie Wagner stranded at second, Marquard walked off the field with a 2-1 victory.

Red Sox victories in the next two games gave them a three games-to-one advantage, and most expected to see a rested Joe Wood on the mound for Boston for a decisive Game Six showdown against Rube Marquard in the Polo Grounds. Under pressure rumored to come from club president McAleer, however, shortly before game time manager Jake Stahl surprised nearly everyone by naming O’Brien as his starter. Perhaps O’Brien was simply not ready to pitch, or perhaps it was just not his day. Whatever the cause, Buck found nothing but trouble when he took the mound against Marquard for a second time. Visibly distracted by John McGraw’s incessant chatter from the third-base coaching box, Buck yielded singles to Larry Doyle and Red Murray, who stood at the corners with two out. He nabbed Josh Devore on a groundout and struck out Fred Snodgrass, but against Fred Merkle he struggled. Intent on checking Murray at first, Buck wheeled away from Merkle toward Stahl, raised his arm to throw, then inexplicably held fire. “That was a balk! Balk! Balk!” howled McGraw, charging toward home plate umpire Bill Klem. Klem agreed and signaled for the baserunners to advance. “He’s gone now!”xxvii McGraw thundered deliriously.

Buck came completely unglued. By the close of the inning he had yielded five runs, prompting Jake Stahl to pull him in favor of Ray Collins. “Why O’Brien was not relieved … after his bad balk is up to Manager Stahl to explain,” complained a bewildered Tim Murnane. “It was only too plain to the boys sitting behind the plate that the Boston moistball artist had ‘nothing.’ ”xxviii Boston battled through every frame thereafter and Collins pitched brilliantly, but in the end the five-run deficit proved too much to overcome. Boston bowed once again to Marquard, this time 5-2. For Buck it was a humiliating defeat and a major turning point in his career. “In Brockton,” recalled O’Brien family friend and lifelong city resident Bob Kane, “they say Buck was never the same pitcher after committing that balk in the World Series.”xxix

It seemed as though Buck disintegrated in front of the fans’ very eyes. Up three games to two, the team glumly steamed back to Boston for Game Seven as the Giants whooped it up in the rear cars. As Buck sat quietly in the Pullman, teammate Joe Wood sauntered by his seat. “Well, you’re a fine joke of a pitcher! Put the game on a platter and handed it to the Giants, didn’t you?”xxx In a flash the two were at each other’s throats, and reports of dissension in the Red Sox camp once again began leaking into the papers.

The two were pried apart the next day, with Wood wielding a baseball bat after Buck punched him in the face, but in the decisive eighth game on a cold and gray October 16, Buck looked on from the bench as Boston triumphed behind Hugh Bedient and Joe Wood in a 10-inning 3-2 thriller. The players celebrated wildly, after which Buck quietly packed his gear and headed for home.

At the Brockton station at 8:01 that evening, he was met by an estimated 3,000 cheering fans, who roared their approval to welcome him home. “What’s the matter, I wonder?”xxxi he said to a half-dozen friends, before realizing it was he who was the center of all the hoopla. He was paraded about town – the crowd far exceeding those who had welcomed Presidents Teddy Roosevelt and William Howard Taft a few years earlier – and landed at the Russell club for the remainder of the evening. At the reception, Buck took the stage to thank his family and all those who had supported him over the years:

I hardly knew what to think when I saw that great mob at the station to greet me. I know no words that can properly express my feelings. To say simply that I appreciate it all is too feeble. No one seems to care whether I won or lost my game in the world’s series. My friends have done themselves proud and the magnitude of this affair is say beyond my every idea. It is something I shall never forget. …xxxii

By the spring of 1913, 30-year-old Buck O’Brien was a ballplayer in his prime, and as his scuffles with Joe Wood during the World Series confirmed, his fighting spirit had diminished not a whisker. To his countless fans back in the Bush, that made all the more bitter the rapid demise of what appeared to be a promising big-league career. O’Brien once again stumbled out of the gate in 1913, but unlike years past, he seemed unable to find his rhythm and control. In all fairness, he was not helped by his slumping teammates, and open warfare between Buck and other members of the team (including owner McAleer) soon exploded. Buck struggled to a 4-9 record through June, and on July 2, over the vehement objections of manager Jake Stahl, McAleer sold him to the Chicago White Sox for $5,000.

If Boston had been a bitter experience for Buck that summer, Chicago was worse. In his debut, on July 11, he bowed to lowly New York, giving up four runs in five innings on eight hits. “Labored is the proper word,” lamented the Chicago Tribune, “for there wasn’t a time in those five rounds when he could take it easy.”xxxiii Five days later, against Philadelphia, he failed to make it out of the third inning. Perhaps he was hurt by a lack of control, but off-the-field battles with Comiskey and several of his new teammates – veteran outfielder Nixey Callahan in particular – did not help matters. On July 29, after just six appearances in the Chicago, Buck was sent packing to Oakland.

Over the next three years, O’Brien bounced from one minor-league club to the next. He remained in the Pacific Coast League for the remainder of 1913, making 16 appearances (111 innings) and posting a 5-5 mark. He returned to Indianapolis in the spring of 1914 and, two solid appearances aside, he struggled persistently. On July 8 manager Jack Hendricks turned him over to the Southern League’s Memphis Chicks, where he fared barely better, notching five wins against six losses in 92 innings of work. Spurning rumors that he was planning to make a jump to the Federal League, in late April of 1915 O’Brien joined the International League Providence (Rhode Island) Grays. His tenure there was short and, once again, rocky. On June 24 he was turned over to the Richmond Climbers in the same league, where he appeared in 16 games and finished the season a disappointing 5-6.

Shortly after his rise to fame with the Red Sox, Buck was introduced to Miss Florence Shea, a young telephone operator from what the O’Brien family recalled as “a proper Cambridge family.” Florence was nine years younger than her famous suitor, and her family was not the least bit impressed by his fearless reputation and glamorous life on the vaudeville stage. “They were not thrilled about her choice in a husband. Not at all,” conceded Rose Moran. “They thought he was just too wild.”xxxiv

Buck continued to pitch locally for the Brockton Colonials that summer, but when manager Eddie Burke relegated him to the bench in late August, he quit and headed to Syracuse in the New York State League to close the year. He appeared three times, winning his first game before being batted around mercilessly in his final two appearances. It marked the end of his professional career.

At the close of the summer O’Brien decided to hang up his professional spikes and stay close to home. He and Florence Shea were married, and within months she was pregnant – time and again. Thomas, Jr. was born in 1917 and John followed two years later. Then came Francis (1921), Killian (1922), Robert (1924), Rachel (1926), and finally Margaret (1927). All the boys, like their father, answered to the moniker Buck.

O’Brien was now a family man, but long after many of the 1912 Boston Red Sox left baseball for other careers, he continued to pitch and sing. Harnessing the notoriety he gained with the Red Sox Quartet, Buck continued performing his old stage numbers in variety shows for the better part of a decade.

And he played ball. He was a “consistent winning pitcher” for the George Dilboy VFW (Somerville, Massachusetts), the Shawmut Council Knights of Columbus, and Walkover Shoes through 1924, and at the age of 43 in 1925, he enjoyed one of the most productive summers of his career, throwing for Walkover and the towns of Amesbury and Rockland. That August he made what may well have been his final appearance, leading the Rockland (Massachusetts) all-stars to a 5-0 victory over Saxony Mills. Fans cheered wildly when it was over, and all looked on with delight as Boston Mayor James Michael Curley presented O’Brien with a gold watch and purse filled to the brim with gold coins. With tears streaming down his face, Buck was so overwhelmed by the gesture that he could barely utter a word of thanks.

When he wasn’t making appearances on the mound and on the stage, through the 1920s and early ’30s, Buck worked with the Boston Parks Department as a coach and director of baseball clinics. As his father had done with him, he instructed his sons in boxing and encouraged them to play ball, but the pressures of playing in the shadow of their famous father was seemingly too much for them. “It’s the same with every ballplayer’s son,” he later lamented to a Boston sportswriter. “From the time they get on the field, they’re the ones that are watched by the fans. If they happened to kick a ball … the wise guy in the stands will say, ‘You’ll never be as good as your old man.’ Well, the result is the boy develops an inferiority complex. It was that way with my boys, and I guess that goes for the rest.”xxxv

In the summer of 1934 the O’Brien family suffered a major setback when Buck fell from the roof of a two-story building into a nest of barbed wire. He suffered massive injuries to his chest, neck, and face and was rushed to the hospital, where he required several bouts of surgery and hundreds of stitches. He remained in intensive care for several weeks.

To help the O’Brien family, a fundraiser was held in Randolph that September, and papers were quick to remind old-time fans of O’Brien’s many contributions over the years. “He was always ready and willing to get out and do his bit for a cause,” the Brockton Enterprise entreated. “There’s scarcely a town where Buck didn’t appear at one time or another, as a singer or speaker.”xxxvi

There were doubts that Buck would ever work again and, according to his daughter, he was out of work for nearly two years. But return to work he did, in 1936, taking a job as a custodian with the Charlestown Boys Club. He remained there until the war came to the United States in 1941. Buck did his part, taking a job as a security guard with Lawley’s Ship Building Company on Port Norfolk in the Neponset neighborhood of Boston, proud producer of “mighty midget” amphibious landing craft.

When the 59-year-old port closed its doors for good in 1945, Buck returned to his old job at the Charlestown Boys Club, where he remained for the next decade until chronic ulcers sidelined him for good. Never forgetting their old friend, when word spread that 73-year-old Buck was gravely ill at Boston’s Carney Hospital after suffering severe hemorrhages and was in dire need of blood, no fewer than two dozen old friends turned up at the Red Cross donation center in Brockton and ponied up a pint apiece on his behalf. That was no surprise to Buck’s old teammate, Howling Dan Howley. “I never knew a more generous fellow,” he said to an interviewer. “Buck must have loaned at least five grand to his old pals, and I don’t suppose he ever got a cent of it back. But that was just the kind of good-hearted guy he was.”xxxvii

Over the next four years Buck continued to battle a variety of ailments, and on the morning of July 25, 1959, his daughter arrived at his Dorchester home to take him to a scheduled medical appointment. Buck never made it. En route to the doctor’s office, Buck suffered a massive coronary occlusion and died. He was 77.

Buck O’Brien was gone, but he would not be forgotten. Three years after his death, he was again honored, this time at Fenway Park, where the surviving Speed Boys returned in April 1962 to mark the 50th anniversary of the championship summer of 1912. In acknowledgement of the first man to throw a pitch at Fenway Park, the honor of throwing out the ceremonial first pitch fell to Buck’s 9-year-old grandson, Tommy O’Brien. He didn’t throw a spitball as his grandfather had, but the young and able athlete did manage a perfect strike that brought cheers from the sellout crowd and an unmistakable sense of pride from O’Brien’s family looking on from the grandstand.xxxviii In appreciation, the club presented Joe and his family with an official Red Sox team jacket, which, like the memory of Buck O’Brien himself, remains a family treasure.

Acknowledgement

The author acknowledges the invaluable help of deceased SABR members Tom Shea, Dick Thompson, and Bob Kane, for their friendship and generous donation of information, insight, and encouragement in the preparation of this article.

Notes

iSporting Life, January 27, 1912, p.14.

iiBrockton Enterprise, April 18, 1907.

iii Author’s telephone conversation with Rosemarie Moran, January 9, 2002.

iv Author’s telephone conversation with Rosemarie Moran, November 5, 2002.

vBrockton Enterprise, August 14, 1944.

vi Boston Post, September 18, 1912, p. 8. The Walkovers’ batboy in 1905 was Francis Joseph Spellman, a youngster out of nearby Whitman and future cardinal of the Catholic Archdiocese in New York.

vii Brockton Enterprise, July 5, 1906.

viii Brockton Enterprise, September 4, 1906.

ix Brockton Enterprise, April 15, 1907, p. 6.

x Brockton Enterprise, August 12, 1907, p. 6.

xi Brockton Enterprise, August 21, 1907, p. 12.

xii Brockton Enterprise, August 30, 1907, p. 12.

xiii Brockton Enterprise, May 21, 1908.

xiv Brockton Enterprise, September 16, 1905.

xv Miscellaneous undated clipping courtesy of SABR member Dick Thompson.

xvi Miscellaneous news clipping courtesy of SABR member Dick Thompson.

xvii Brockton Enterprise. October 28, 1909.

xviii Brockton Enterprise. December 22, 1911.

xix Rocky Mountain News, June 9, 1911, p. 8.

xx Miscellaneous news clipping courtesy of SABR member Bob Kane.

xxi Brockton Enterprise, September 11, 1911.

xxii Boston Globe, September 10, 1911, p. 16.

xxiii Brockton Enterprise, September 11, 1911.

xxiv Brockton Enterprise, September 23, 1911.

xxv Brockton Enterprise, December 11, 1911.

xxvi Boston Globe article as quoted in Brockton Enterprise, April 1, 1912.

xxvii Miscellaneous news clipping courtesy of SABR member Bob Kane.

xxviii Boston Globe, October 15, 1912, p. 6.

xxix Author’s interview with Bob Kane, February 6, 2002.

xxx Mathewson, Christy. “Why we lost three world’s championships,” Everybody’s Magazine, October 1914, reprinted in http://www.leaptoad.com/raindelay/matty/whywelost.shtml. Accessed April 7, 2011.

xxxi Miscellaneous news clipping courtesy of SABR member Bob Kane.

xxxii Brockton Enterprise, October 17, 1912.

xxxiii Chicago Tribune, July 12, 1913,

xxxiv Author’s telephone conversation with Rosemarie Moran, November 5, 2002.

xxxv Boston Traveler, December 4, 1946.

xxxvi Brockton Enterprise, September 27, 1934.

xxxvii Miscellaneous news clipping courtesy of SABR member Dick Thompson.

xxxviii Author’s telephone conversation with Rosemarie Moran, January 9, 2002.

Full Name

Thomas Joseph O'Brien

Born

May 9, 1882 at Brockton, MA (USA)

Died

July 25, 1959 at Boston, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.