Johnny Oates

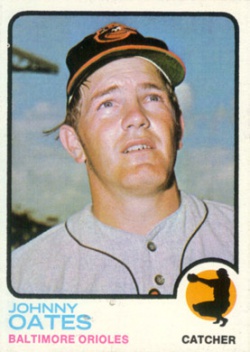

In the first years of Tommy Lasorda’s Hall of Fame career as manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers, he kept several large photographs on the walls of his office at the team’s spring-training complex in Vero Beach, Florida. There was one of himself and Walter Alston, his legendary predecessor, and another with Hall of Fame sluggers from the Dodgers “Boys of Summer” days in the 1950s. Finally, there was a photograph of his third-string catcher swinging a bat. Johnny Oates rarely struck that pose while playing for Lasorda – he made only 126 appearances for the Dodgers skipper in three seasons.

In the first years of Tommy Lasorda’s Hall of Fame career as manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers, he kept several large photographs on the walls of his office at the team’s spring-training complex in Vero Beach, Florida. There was one of himself and Walter Alston, his legendary predecessor, and another with Hall of Fame sluggers from the Dodgers “Boys of Summer” days in the 1950s. Finally, there was a photograph of his third-string catcher swinging a bat. Johnny Oates rarely struck that pose while playing for Lasorda – he made only 126 appearances for the Dodgers skipper in three seasons.

When asked why the journeyman catcher’s picture was up on the wall with all of those Hall of Famers, Lasorda replied, “He’s just a terrific guy, one of my favorites.” It was a sign of the high esteem in which the baseball world always held Johnny Oates.1

For many respected men who die before their time, their reputations are often enhanced after their lives are over. Johnny Oates’s legacy was forged long before his death at the age of 58 in 2004 from an aggressive form of brain cancer.

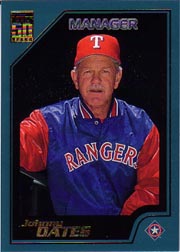

As a player for 11 seasons, Oates was a favorite of managers — Earl Weaver in Baltimore, Lasorda in Los Angeles, Dick Howser in New York — and as a manager, who guided the Texas Rangers to their first playoff appearance in franchise history, Oates was favored by his players. He managed four MVPs in his 11 seasons at the helm, and finished with a 797-746 career record. As of 2010, Oates and Hall of Famer Frank Robinson were the only two men to play for, coach, and manage the Baltimore Orioles.

But it was Oates’s honesty and integrity that earned him respect from those who crossed his path. Baseball executive Doug Melvin, who hired him for two managerial positions, said, “He touched a lot of people, and that’s what makes people special in this world. He always had a relationship with his players that goes beyond just a working relationship. That’s rare. Not everybody is like that, especially in a highly competitive field as this one.”2

Johnny Lane Oates was born on January 21, 1946, in Sylva, North Carolina, a town nestled in the Great Smoky Mountains in the western part of the state. He was the fourth of Clint and Madie (nee Franks) Oates’ five children. Clint eked out a living cutting cabbage, with Madie’s help. The family had no indoor plumbing or electricity, and an army cot served as a couch in their living room. With the encouragement of his father, who had played for sandlot and mill teams, Johnny learned to play baseball on the hillside with his brothers, avoiding the snakes when an errant throw went into the brush.3

Clint learned to cut sheet metal and took a job at Fort Bragg in Fayetteville, North Carolina, where Johnny began playing organized ball on a Royal Ambassador team. (The Royal Ambassadors are a Southern Baptist-sponsored program for young boys.) He was a catcher from the beginning – in his first game, the coach asked Oates if he could play the position. “No, I can’t,” he said. “Yes, you can,” his father said from the stands. And so he did.4

When Johnny was in the eighth grade, the family moved to Petersburg, Virginia. Clint took his son to his first major-league game, at Washington’s Griffith Stadium, in 1961. He recalled seeing Mickey Mantle hit a home run that weekend, and one of his prized possessions later in life was a baseball autographed by the Yankees slugger.5

Oates starred in baseball, basketball, and football at Prince George (Virginia) High School, hitting .523 as a senior to earn all-conference honors. He entered Virginia Polytechnic Institute in 1965. He played two years of varsity baseball for the Hokies, and became the first player from that school to be drafted when he was selected by the Chicago White Sox in the second round in 1966. Oates decided to return to school for his junior season, but was selected again by the Baltimore Orioles with the 10th overall pick of the secondary draft in January 1967. He signed with the Orioles on the provision that he would stay in school until June to finish his spring classes, and he later graduated with a degree in health and physical education. Oates’s No. 15 became the first baseball jersey retired at Virginia Tech in 2002, and a memorial award was established in 2006 to honor the player who exemplified Oates’s faith, character, and perseverance.6

On August 12, 1967, Oates married his high-school sweetheart, Gloria Jackson. They had continued dating for five years even though Gloria had gone to East Carolina University in Greenville, North Carolina, and Johnny was at Virginia Tech. It was a relationship that would last more than four decades, producing three children. Gloria understood and accepted her new role as a baseball wife. “Even if he’s 3,000 miles away, he always calls and says, ‘I’m with you,’” she said years later.7

After a week in the rookie-level Appalachian League, Oates joined the Orioles’ Class A affiliate in the Florida State League. In Miami, his manager was Cal Ripken Sr., who had been a catcher a decade earlier in the Orioles organization. Ripken was charged with teaching his 21-year-old prospect about the position. He would stand at the mound and hit hard fungoes at Oates, saying, “If you can block these, you can block any pitch.” The pair talked baseball for hours. Oates said later, “I don’t think there was anyone who knew more about the game.”8

Oates reported to the Orioles’ spring-training camp in 1968, catching batting practice and warming up the pitchers. “I was excited,” he said, “maybe a little bit in awe. They had Frank Robinson, Brooks, Boog, a championship-type ball club. … It was my first association with all those people I’d seen on TV.” But Oates still needed a lot of seasoning in the minor leagues, and was sent back to Miami that season. He played well enough to earn a call-up in 1969 to the Double-A Texas League, where he hit .288 and made just four errors in 66 games for Dallas-Fort Worth.9

In 1970 Oates got his first taste of the big leagues, when he made five appearances for the eventual World Series champion Orioles in the final month of the regular season. He made his major-league debut on September 17, 1970, when he pinch-hit for shortstop Mark Belanger to lead off the ninth inning in a game at Washington’s Robert F. Kennedy Stadium, just two hours north of where he had grown up in Virginia. Facing 16-game winner Dick Bosman, Oates singled to left field in his first at-bat but was stranded there as the Orioles lost 2-0. Oates got his first start the next day at home against Cleveland. He went 1-for-4 and threw out a pair of would-be base stealers at second.

But Oates’s time in Baltimore was frustrating. Stuck behind veterans Andy Etchebarren and Ellie Hendricks, the 25-year-old spent the entire 1971 season at Triple-A Rochester, where he hit .277 in 114 games and made just six errors. The Red Wings finished first in the International League, but Oates was itching for a chance to return to the big leagues.

In 1972, he took advantage as injuries limited Etchebarren and Hendricks, and Oates made the majority of the starts for Hall of Fame manager Earl Weaver. But Baltimore’s run of three consecutive American League pennants ended and, when the Orioles had a chance that off-season to acquire Atlanta’s slugging catcher, Earl Williams, Oates was deemed expendable and included in a trade to the Braves with second baseman Davey Johnson and pitcher Pat Dobson.

Oates was a pleasant surprise for the Braves, batting as high as .310 near the end of April 1973, and seemed a lock to keep his place in the lineup even after his average fell off. However, in mid-July – an Atlanta paper said he was “just coming into his own” then10 – Oates sustained the first of a series of injuries that hampered the rest of his playing career. He strained a ligament in his knee running out a ground ball against the New York Mets and did not return to the team until early September.

Nagging injuries continued to limit Oates in 1974; although he played a career-high 100 games (including a pinch-hitting appearance on April 8, the day that Henry Aaron hit his record-breaking 715th home run), he made just 10 starts after Clyde King replaced Eddie Mathews as the Braves’ manager in July. Oates made his displeasure known to Braves General Manager Eddie Robinson, who sent him to Philadelphia with outfielder Dick Allen after the latter had refused to report to the Braves to start the 1975 season. “This will give Oates a chance to play more regularly,” Robinson said at the time.11

Oates thrived in Philadelphia, and so did the Phillies. After making five pinch-hit appearances, Oates began a career-high 11-game hitting streak on June 10 at San Diego. He hit .313 during the streak, raising his average 38 points; he also reached base in 18 consecutive games. The Phillies surged to second place in the NL East behind Pittsburgh, finishing above .500 for the first time in a decade.

But Oates was still hurting, and he had surgery to repair ligaments in his left knee at Philadelphia’s Methodist Hospital in November, returning in time to open the 1976 season as the Phillies’ starting catcher. His good health lasted almost nine innings. On Opening Day Pittsburgh’s Dave Parker crashed into Oates and knocked the ball from his grasp to score the game-tying run in the ninth. A broken left shoulder kept Oates out until June 3, by which time he had lost his job to Bob Boone. “One play turned my entire year around,” Oates said.12

The Phillies won their first National League East Division title that year, and Oates made a token appearance in the final game of the League Championship Series against the Cincinnati Reds. But in the off-season, a month before his 31st birthday, he was traded again – this time to Los Angeles, where he was expected to back up catcher Steve Yeager. New manager Tommy Lasorda took a liking to Oates immediately. A later Los Angeles Times profile explained why: “Oates understands his job and does it well. Maybe that’s why he is such a favorite. He doesn’t make a manager nervous. … No waves, no rocking boats.”13

Oates did not see much playing time in a Dodgers uniform, but he did earn two National League championship rings – and reached base twice in the late innings of Game Five of the 1978 World Series, singling off the Yankees’ Jim Beattie for his only postseason hit. (He had also played two innings in Game Five of the previous year’s World Series against New York.)

By 1980, the Dodgers had little room for a weak-hitting, injury-prone, 34-year-old backup catcher. Oates was released at the end of spring training and offered a job in the organization. He preferred to keep playing, however, and on a recommendation from former Dodgers teammate Tommy John, the Yankees signed him as a free agent a week later.

He saw the writing on the wall. “The only time I caught,” Oates said, “was when we were 10 runs behind or 10 runs ahead. But Dick Howser made me feel so good about myself.” The following year, the Yankees offered him a minor-league contract but later guaranteed his major-league salary after John and fellow pitcher Tommy Underwood stood up for him with management.14

In May, the Yankees were taking batting practice before a game in Cleveland when manager Gene Michael approached the catcher. Oates recalled, “I knew what was coming. They just told me to come into the office and talk, and I told them whatever they had to tell me I could take standing up in the dugout.”15 He was sent to Triple-A Columbus as a player-coach, but he didn’t take the field ever again. Oates ended his career with a .250 average in 593 games, but he took more pride in his defense, having caught eight pitchers with at least 200 victories (Gaylord Perry, Luis Tiant, Tommy John, Jim Kaat, Steve Carlton, Phil Niekro, Don Sutton, and Jim Palmer.) “I was a very lucky ballplayer because I was always with the right team at the right time,” he said.16

Like many ballplayers, Oates didn’t hang ’em up without a few regrets. “The one thing that disappoints me most about my career is that I didn’t enjoy it,” he said. “I was always worried about being released, being traded. I was a fringe player and all I thought about was surviving from one day to the next.”17

In 1982, Oates took the reins of the Yankees’ Double-A affiliate in Nashville, Tennessee. His immediate task, aside from adjusting to life as a young manager, was to help develop the most promising catcher in the organization, Scott Bradley, who went on to play nine seasons in the majors.18 In the meantime, Oates led the Nashville Sounds to a 77-67 finish in the Southern League and earned a promotion to Columbus in 1983, when he led the Triple-A Clippers to an 83-57 record and a berth in the Little World Series.

Oates was offered a chance to return to the major leagues in 1984 as a bullpen coach with the Chicago Cubs, who needed an experienced catcher to help Jody Davis shore up his defense. Under Oates’s guidance, Davis became an All-Star for the first time and Chicago won the National League East title. Oates stayed on as bullpen coach for two more seasons, then replaced Ruben Amaro as bench coach under manager Gene Michael. After Michael resigned in 1987, Oates was considered one of the leading contenders to get the Cubs’ head job but he lost out to Don Zimmer.

For the first time, Oates began to consider life after baseball. Several years before, he had become involved with the Virginia franchise of an advertising specialty company as a sales associate. Soon the Orioles came calling, asking their former player to manage again in Triple-A in 1988. Saying “baseball was in my blood,” Oates accepted the job with Rochester and proceeded to win the International League’s manager of the year award. (The Red Wings also had the league’s MVP, Craig Worthington, and rookie of the year, Steve Finley.)19 After being passed over for the Toronto Blue Jays’ managerial job that off-season, Oates returned to Baltimore for the first time in nearly two decades to serve as Frank Robinson’s first-base coach in 1989.

He also enjoyed reuniting with Cal Ripken Sr., his old manager. Oates and his wife, Gloria, often spent time at the Ripkens’ house in Aberdeen, swimming and throwing horseshoes. According to Cal Ripken Jr., Oates “lived for the day when Dad would bring the first box of his Better Boys in the clubhouse” so he could make his favorite sandwiches, tomato and mayonnaise, a staple of his youth in the mountains of North Carolina.20

It didn’t take long before Oates’s name was mentioned as Robinson’s possible successor. He managed the Orioles to a 2-1 record during the latter’s suspension in June 1990. When the Orioles lost 24 of their first 37 games in 1991, Oates’s time had come. On May 23, he became the ninth manager in franchise history. General Manager Roland Hemond said at the time, “I had my eye on him. I had concerns at some point that he’d be managing another club. … We’re fortunate to have him around.”21

It didn’t take long before Oates’s name was mentioned as Robinson’s possible successor. He managed the Orioles to a 2-1 record during the latter’s suspension in June 1990. When the Orioles lost 24 of their first 37 games in 1991, Oates’s time had come. On May 23, he became the ninth manager in franchise history. General Manager Roland Hemond said at the time, “I had my eye on him. I had concerns at some point that he’d be managing another club. … We’re fortunate to have him around.”21

The strain that Oates had felt as a fringe player in the major leagues just increased exponentially as a manager. As his Orioles lost their first four games, Oates lost nine pounds and his diet was reduced to a bowl of soup and half a sandwich per day. He lost weight so quickly, reported the Washington Post, that Hemond was prompted to deliver a huge ice-cream sundae to Oates’s office after his first victory.22 He remained a nervous wreck that whole season. He kept the walls of his office at Memorial Stadium bare until the Orioles players’ “kangaroo court” fined him for waiting five days to begin managing – and then instructed him to use the money to start decorating. By then, it was nearly time to move into Camden Yards.23

Oates had a lot to look forward to in 1992. Besides the sparkling new stadium, and the league’s reigning MVP in Cal Ripken Jr., Oates had also signed a multiyear contract – for only the second time in his life – and could now concentrate on building a winner in Baltimore. He lured an old teammate, Rick Sutcliffe, to be the Orioles’ ace and the veteran right-hander responded with 16 victories. The Orioles won 89 games in Oates’s first full season, their most since winning the World Series in 1983, but the end of the year was marred when Oates was forced to fire his old friend Cal Ripken Sr. from the coaching staff.24

Oates’s tenure in Baltimore came under further strain after Peter Angelos took over as owner in 1993. Although the Orioles won 85 games that year (with Oates earning Manager of the Year honors from The Sporting News) and finished the strike-shortened 1994 season with a .563 winning percentage – the highest of Oates’s career to that point – he still faced constant questions about his job security. Angelos seemed “bent on firing him,” and before baseball finally came back from the work stoppage, he did.25

Oates wasn’t out of a job for long. In Texas, General Manager Doug Melvin – who had hired him in Rochester back in 1988 – brought him in to manage the Rangers, a franchise with four 80-win seasons in the last six but which couldn’t quite get over the hump and into the postseason. It was Johnny Oates who finally led them there.

Rangers outfielder Rusty Greer said, “I don’t think it’s any coincidence that Juan (Gonzalez) won two Most Valuable Player awards under Johnny or that Pudge (Ivan Rodriguez) won his MVP under Johnny. Johnny got the most out of each player and knew what buttons to push. He allowed each player to be themselves.”26

What Oates hadn’t been doing was allowing his family to be themselves. By his own admission, “the job had me so wrapped up that it … ruled my life.” He had missed all three of his kids’ baptisms and graduations. But that all changed before his first game with the Rangers. His wife, Gloria, woke up one morning during spring training with a major panic attack and was rushed to the hospital. “My wife is dying and my focus is still on baseball?” Johnny asked himself. As Gloria recovered, Oates took a two-week leave of absence from the team – missing Opening Day – and went home to Virginia to begin counseling with his wife, and to renew his faith. He vowed not to let his intensity cause him to lose perspective about his job. Soon, he noticed that his team had better focus, too.27

In 1996, with MVP Gonzalez leading the way and Oates a changed man in the dugout, the Rangers powered to 90 wins, their first American League West title and the first playoff appearance in franchise history. For his efforts, Oates shared the American League’s Manager of the Year Award with the Yankees’ Joe Torre. Torre, however, got the best of him in the division series, winning three out of four games as New York went on to claim its first championship in nearly two decades.

The Yankees became Oates’s nemesis in the playoffs for the rest of the decade – the Rangers also won the AL West in 1998 and ’99 but were swept by New York in the first round each year. But getting past the Bronx Bombers would soon be the least of his concerns. New owner Tom Hicks assembled an unbalanced team, heavy on hitting but low on pitching, that sank into last place; Oates decided to step down from the Rangers in May 2001, saying, “I’m all out of buttons to push.” He handed over the team to his friend and third-base coach, Jerry Narron. He spent the rest of the year with his family, taking daily walks with his wife, spoiling his grandchildren, watching ballgames on TV. It was his first summer without baseball since he was 11 years old.

Two days after the 2001 World Series ended, Oates, then 55, learned he had cancer. Not just any cancer, but glioblastoma multiforme, one of the most aggressive forms of brain tumors and the same ailment that former Royals pitcher Dan Quisenberry and his former manager Dick Howser had died from. The diagnosis was grim: he was given 14 to 18 months to live, even after doctors had removed the tumor through surgery. He promised his daughter Jenny that he would live to see her wedding the following August, and he did. “This is not a script I’ve written for myself,” he said. “I’d rather be managing a ballclub somewhere. But this is what I’ve been dealt. And I’m at peace with it.”28

The outpouring of support for Oates from his baseball friends was immense. On Opening Day 2002, he returned to Camden Yards to throw out the first pitch for the Orioles and was given a standing ovation. He had already been inducted into the Virginia Tech Sports Hall of Fame (1983); Virginia High School Sports Hall of Fame (1992); Salem-Roanoke Baseball Hall of Fame (1994); Texas Baseball Hall of Fame (1997); Rochester Red Wings Hall of Fame (2000); and Jackson County (North Carolina) Sports Hall of Fame (2001) – now, he added the Virginia Sports and Texas Rangers halls of fame to that list. In 2003, the Rangers honored Oates along with Nolan Ryan, Jim Sundberg, and Charlie Hough in an on-field ceremony in Arlington. Oates received the loudest applause from a sellout crowd. That night, the humble former manager said, “The difference between these guys and myself is they’re here because of what they did. I’m here because of what others did for me.”29

Oates’s cancer returned in April 2003. This time, neither surgery nor chemotherapy could keep the tumor away. With his wife and brother at his side, Oates died on December 24, 2004, at Virginia Commonwealth Medical Center in Richmond. He was 58.

Posthumously, Oates was honored by the Virginia General Assembly and his number 26 was retired by the Rangers in 2005. Buck Showalter, his former player and coach and one of his best friends, renamed the Rangers’ manager’s office for Oates. “There is not a day that goes by that I do not use some of the advice that he gave me over the years,” Showalter said. “Nobody epitomized more than Johnny what we want to do and how we should handle ourselves as professionals in this game.”30

Notes

1 John Hall, “An Old Face, Warm Smile,” Los Angeles Times, March 4, 1980.

2 Peter Schmuck and Bill Free, “A Man of Faith, Life of Integrity,” Baltimore Sun, December 25, 2004.

3 Johnny Oates, “Living With Full Count,” The Baptist Standard, Interviewed by Toby Druin, accessed at http://www.baptiststandard.com/2001/9_3/print/oates.html, October 28, 2008.

4 Tom Callahan, “Oates May Need His Old Padding,” Washington Post, May 26, 1991.

5 Johnny Oates, “Living With Full Count.”

6 Johnny Oates, “Living With Full Count;” “Johnny Oates,” Hokiesports.com, accessed at http://www.hokiesports.com/baseball/jerseys/oates.html, October 28, 2008; “Hamilton, Oates, Stillwell to join Athletic Hall of Fame,” Sylva (North Carolina) Herald, April 11, 2002, accessed at http://www.thesylvaherald.com/SP-HallofFame041102.htm on November 17, 2008.

7 Johnny Oates with Dennis Tuttle, “All I Can Do Is Be Excited About Today,” The Sporting News, April 22, 2002; Steve Berkowitz, “Now, Detail-Man Oates Must Answer Questions,” Washington Post, May 24, 1991.

8 Richard Justice, “Oates Recalls Mentor Ripken Sr.,” Washington Post, May 19, 2000; Cal Ripken, Jr. and Mike Bryan, The Only Way I Know (New York: Penguin Books, 1997).

9 Jane Gross, “Yankee Veterans Find Different Style but Same Routine in Spring,” New York Times, Feb. 23, 1981.

10 Atlanta Daily World, February 24, 1974.

11 “Braves Trade Dick Allen, Johnny Oates to Phillies,” Atlanta Daily World, May 11, 1975.

12 Ross Newhan, “Dodgers Obtain Oates; Sizemore Sent to Phillies,” Los Angeles Times, December 21, 1976.

13 John Hall, “An Old Face, Warm Smile.”

14 Dave Anderson, “Yanks’ Johnny Oates Is In Good Spot,” New York Times, April 23, 1981.

15 Chicago Tribune, May 31, 1984.

16 Michael Martinez, “He Had A Heart, And For Oates, That Was The Problem,” New York Times, May 26, 1991.

17 Michael Martinez, “He Had A Heart.”

18 Jane Gross, “Foote, Gulden Compete to be Backup Catcher,” New York Times, March 12, 1982.

19 “Around the Majors,” Washington Post, August 23, 1988.

20 Ripken Jr. and Bryan, “The Only Way I Know.”

21 Mark Maske, “Orioles Cut From Top – Put Oates in for Robinson,” Washington Post, May 24, 1991.

22 Mark Maske, “‘Relax’ Has No Place in Oates’s Vocabulary,” Washington Post, September 13, 1992.

23 Mark Maske, “Pressure Keeps Pounds Off Oates, But Appetite for Managing Grows,” Washington Post, April 5, 1992.

24 Ripken Jr. and Bryan, “The Only Way I Know.”

25 Frank Dolson, “For A Lesson in Confusion, Look at Position of Johnny Oates,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 9, 1994; Thom Loverro, “Maybe He Finally Can Find Peace,” Washington Times, December 25, 2004.

26 T.R. Sullivan, “A Great Baseball Man … A Great Human Being,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, December 25, 2004.

27 Johnny Oates with Dennis Tuttle, “All I Can Do Is Be Excited About Today;” Thomas Boswell, “Oates Is No Longer Playing the Averages,” Washington Post, March 26, 2002.

28 Thomas Boswell, “Oates Is No Longer Playing the Averages”; Jorge Arangure, Jr., “Former O’s Manager Oates Dies,” Washington Post, December 25, 2004.

29 “Johnny Oates,” Sports Encyclopedia, accessed online at http://www.sportsencyclopedia.com/memorial/tex/oates.html on Nov. 18, 2008; “Rangers Honor Former Manager Oates,” Washington Post, April 12, 2005.

30 “Former Texas Rangers Manager Johnny Oates Passes Away,” MLB.com, Dec. 24, 2004.

Full Name

Johnny Lane Oates

Born

January 21, 1946 at Sylva, NC (USA)

Died

December 24, 2004 at Richmond, VA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.