August 10, 1883: Cap Anson vs. Fleet Walker

The beginning of the end of African American participation in Organized Baseball probably dates to an in-season exhibition game less than two decades after the close of the Civil War.

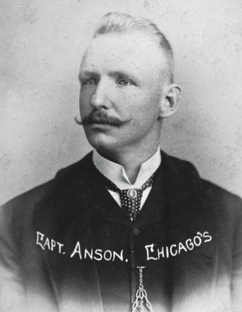

Cap Anson’s Chicagos were a model of success on the field, having won the three previous National League titles, and at the time of the game they were in the thick of a battle for a fourth straight. Anson was their very capable leader, a Hall of Fame-bound player and by modern standards an outspoken racial bigot. His views were hardly unique at the time, within baseball or in the country at large, but his prominent position made him a major factor in segregating the game.

Baseball in Toledo was in its infancy, the 1883 season being the city’s first. The Toledo catcher was Moses Fleetwood Walker, a mulatto man1 and the target of Anson’s prejudice. Walker was one of just a few black men playing in the minor leagues at the time. His race nearly denied him that opportunity. The executive committee of the Northwestern League met at Toledo’s Boody House on March 14, 1883, to consider “a motion … by the representative from the Peoria, Illinois, club that no colored player be allowed in the league.”2 This action was made specifically to expel Walker. After a bitter fight, the motion was defeated, allowing Walker to play.

Unfortunately for researchers, only one Toledo newspaper containing the game account and the events leading up to it survives. The Toledo Daily Blade’s lengthy account is not at all complimentary of either Anson or his team. In fact it is exceedingly supportive of Walker and indicates that the Toledo management came to his defense and suggests that the city did as well. The article is replete with opinion and appeared under several headlines including “Baby Anson and the Color Line.”3 It is repeated here in part:

Walker, the colored catcher of the Toledo Club … was a source of contention between the home club and … the Chicago Club. Shortly after their arrival in the city … the Toledo Club was … informed that there was objection in the Chicago Club to Toledo’s playing Walker.…

Walker has a very sore hand, and it had not been intended to play him in yesterday’s game, and this was stated to the bearer of the announcement for the Chicagos. … Not content with this, the visitors … declared with the swagger for which they are noted, that they would play ball “with no d—-d nigger.” … (T)he order was given, then and there, to play Walker and the beefy bluffer was informed that he could play or go, just as he blank pleased. Anson hauled in his horns somewhat and “consented” to play, remarking, “We’ll play this here game, but won’t play never no more with the nigger in.”4

Toledo’s manager, Charlie Morton, had called Anson’s bluff, forcing the latter onto the field in order to secure his interest in the day’s gate receipts.

Toledo’s manager, Charlie Morton, had called Anson’s bluff, forcing the latter onto the field in order to secure his interest in the day’s gate receipts.

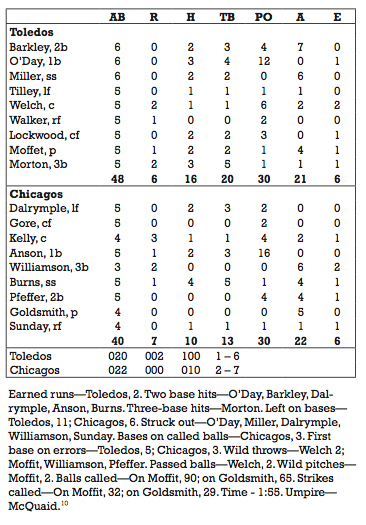

Contrasting the Toledo reporting, the Chicago Tribune’s brief story contained only basic game information and was not accompanied by a box score. “Ten innings were played today between the Chicagos and the Toledos, and the former barely succeeded in defeating the home nine, securing but one additional run on the extra inning. The score stood 7 to 6 and the home nine felt proud of having succeeded in holding down the league champions to their work.”5

Toledo secured two moral victories that day. Their manager and team had taken the high road by supporting Walker. Of lesser importance was their play, which forced the powerful Chicago team to extra innings. Most of the Chicago team had been together for several years and included two future Hall of Famers, Anson, the 19th century’s best hitter, and colorful catcher King Kelly. The supporting cast included Billy Sunday, who went on to become a noteworthy evangelist.

But Anson made good his bold statement — “won’t play never no more with the nigger in.”6 Chicago was at Toledo again in 1884 but this time Walker did not play. The reason is not clear, but Chicago had requested assurance in writing that no black would play any position in the July 25 exhibition game.7 Toledo’s response to this request is not known, but it is known that Walker had not played the previous three games because of injury, nor did he catch again until August 18. Teams featuring Walker and Anson met again in Newark in 1887 with Walker on the sidelines along with his black batterymate, George Stovey.8 Walker left after the 1889 season, “The last black to play in a highly competitive integrated league”9 until the arrival of Jackie Robinson in 1947.

Cap Anson was not entirely responsible for baseball’s more than half-century of segregation, but he had a lot to do with it. The incident of August 10, 1883, in Toledo certainly brought the issue to the forefront and began an open, blatant, and successful effort to bar black players from Organized Baseball.10

This essay was originally published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here.

Notes

1 Zang, David W. Fleet Walker’s Divided Heart (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995), p. 2.

2 Toledo Daily Blade, March 15, 1883, p. 3.

3 Toledo Daily Blade, August 11, 1883, p. 3.

4 Toledo Daily Blade, August 11, 1883, p. 3.

5 Chicago Daily Tribune, August 11, 1883, p. 2.

6 Toledo Daily Blade, August 11, 1883, p. 3.

7 Rosenberg, Howard W. “Recapping a Bit of Toledo’s History,” The Blade, November 8, 2006, C 2.

8 Rosenberg, Howard W. “Cap Chronicled-Cap’s Great Shame- Racial Intolerance,” at www.capanson.com.

9 Zang, p. 61.

10 Toledo Daily Blade, August 11, 1883, p. 3.

Additional Stats

Chicago White Stockings 7

Toledo Blue Stockings 6

League Park

Toledo, OH

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.