August 26, 1869: Cincinnati Red Stockings: Unbeaten, But Tied

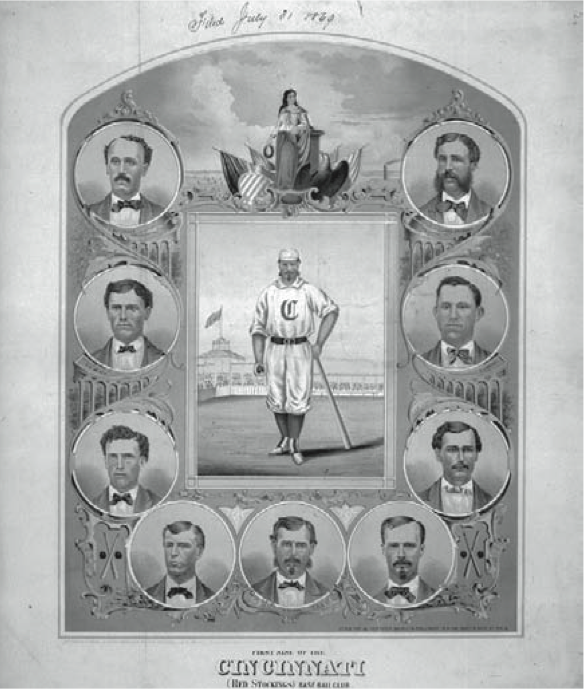

By August 1869 the Cincinnati Red Stockings had become the top baseball club in the country. Not only were they undefeated, but the novelty of their all-salaried status, their distinctive uniform style with the long red socks, and the triumphs over all the top Eastern clubs had made them the center of attention in the sporting press.

A handful of the Eastern clubs that the Red Stockings played on their long June tour had traveled west that summer to take on the Red Stockings (and other teams in the Midwest), and the Cincinnati boys had taken their measure. They defeated visitors from Washington, Syracuse, and New York City. But the game that was most anticipated was scheduled for Thursday, August 26, when the Unions of Lansingburgh, New York (now a part of Troy), better known as the Haymakers, invaded the Queen City for one game.

A handful of the Eastern clubs that the Red Stockings played on their long June tour had traveled west that summer to take on the Red Stockings (and other teams in the Midwest), and the Cincinnati boys had taken their measure. They defeated visitors from Washington, Syracuse, and New York City. But the game that was most anticipated was scheduled for Thursday, August 26, when the Unions of Lansingburgh, New York (now a part of Troy), better known as the Haymakers, invaded the Queen City for one game.

A week before the match the club ran newspaper ads saying, “The Haymakers are Coming.” Such a warning was probably wise, given the notorious crowd that accompanied the visitors. Charges of bribery, fixing games, gambling, and ungentlemanly behavior dogged the Lansingburgh team. “The Haymakers, while strong players, are not of good reputation,” warned the Cincinnati Commercial on the eve of the match.

Yet the staid and sober management of the Red Stockings, led by club president Aaron Champion and captain Harry Wright, agreed to host the Haymakers on their home grounds. The championship race, as it was in this era, was often abused by clubs that refused to play contenders, sometimes even failing to show up for scheduled matches. Champion and Wright wanted no taint or imputation of cowardice to besmirch the glory of the Red Stockings, so the invitation was accepted, the match scheduled and heavily advertised.

Some anticipated problems. The Commercial warned the Cincinnati faithful to remain calm and not soil the reputation of the Red Stockings during the match, even if the play of the Haymakers or the decisions of the umpire riled them. Crowds, especially in the East, “get to acting outrageously at times and start to hissing,” the newspaper’s correspondent asserted. “We sincerely hope nothing of this kind will occur at base ball games in this city.”

Cincinnati’s hotels swarmed with visiting and local baseball men on the eve of the game. The lobbies and private rooms at the Gibson House, where the Haymakers stayed, were the “scene of great animation.” Betting was reported to be very heavy, and rumors swirled that some of the Cincinnati players had been approached to fix the game. The most prominent backer of the Haymakers, Congressman John Morrisey, had a $17,000 bet on his club, according to the whispers floating about the city.

By noon the streetcars were jammed and pedestrians filled the streets heading to Union Grounds, the Red Stockings’ park in the city’s West End. The temperature neared 90, but a breeze brought some comfort. By game time, the baseball correspondent for the Cincinnati Commercial, Henry Millar, estimated the crowd was 10,000. Although the club put up temporary seats for an additional 2,000 spectators, standees were a dozen deep, and carriages stood in a line in foul ground stretching all the way into right field against the fence. After the teams warmed up on the field for a few minutes, John Brockway, an experienced umpire, tossed the coin; the Haymakers won the toss and sent the Red Stockings to the bat.

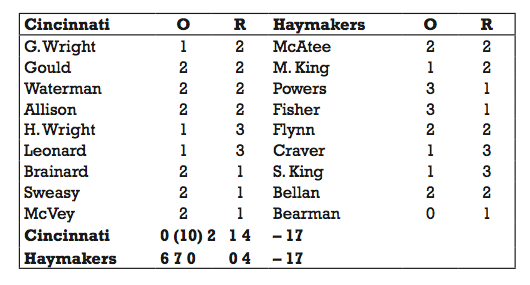

The Red Stockings gave up six runs in the bottom of the first, mainly due to some heavy hitting and dropped fly balls by outfielders Andy Leonard and Cal McVey. The rumor mill ground on. Were the Red Stockings on the take? Was pitcher Asa Brainard in cahoots with the New Yorkers? But the Cincinnati nine answered those questions in the top of the second with 10 runs.

The Red Stockings gave up six runs in the bottom of the first, mainly due to some heavy hitting and dropped fly balls by outfielders Andy Leonard and Cal McVey. The rumor mill ground on. Were the Red Stockings on the take? Was pitcher Asa Brainard in cahoots with the New Yorkers? But the Cincinnati nine answered those questions in the top of the second with 10 runs.

The scoring continued at a fierce pace, and by the end of the fifth inning, the boards showed each team with 17 runs. Millar wrote that he had “never witnessed such an overwhelmingly excitement-soaked crowd.” McVey led off the sixth inning for Cincinnati and sent a foul ball spinning back to Haymaker catcher Bill Craver. The batter was out if the catcher caught the ball in the air or on the first bounce. The ball hit the ground, and Craver lunged, scraped the ground with his hand, and finally held the ball up. “How’s that?” he shouted at the umpire. Brockway ruled that it had bounced twice. It was obviously a close call. Two Cincinnati reporters sitting at a table on the field could not agree whether Craver had caught it fairly.

The play seemed to have little consequence. No one was on base. McVey was the first batter in the sixth. The Haymakers had just scored four times in the fifth, and seemed to be giving the Red Stockings all they could handle. But the president of the Haymaker club, a man named McKeon, charged onto the field to argue the call with Brockway. Perhaps sensing that the Red Stockings, who were noted for late-inning hitting and scoring, seemed likely to take control of the game, McKeon was looking for an excuse to end the match and protect his associates’ bets. After a brief conversation with the umpire, McKeon waved his players off the field.

Despite the newspaper’s admonition, the crowd began hissing. Brockway ordered the Haymakers to remain on the field. “It’s none of your damned business,” shouted McKeon, and the Haymakers boarded the carriage for the ride back to the hotel, the taunts and jeers of the spectators filling the air.

The umpire waited a few minutes, then climbed on a chair and announced to the crowd that the match was over and that he was awarding victory to the Red Stockings. Champion refused to give the visitors their share of the gate money (which he did turn over the next summer). The local and national newspapers were full of denunciations of the Haymakers’ behavior. The victory was later declared a tie by the governing body of the day, the National Association of Base Ball Players, although the rules did call for a forfeit if one team was prepared to play and the other failed to take the field. Thus ended the only game the Red Stockings did not win outright that season. They eventually stretched their unbeaten streak to 57 games. They did not play the Haymakers again in 1869.

This essay was originally published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here.

- Related link: June 14, 1870: The Atlantic Storm: Red Stockings suffer first defeat (SABR Games Project)

Additional Stats

Cincinnati Red Stockings 17

Haymakers of Troy 17

Union Grounds

Cincinnati, OH

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.