June 14, 1870: The Atlantic Storm: Red Stockings suffer first defeat

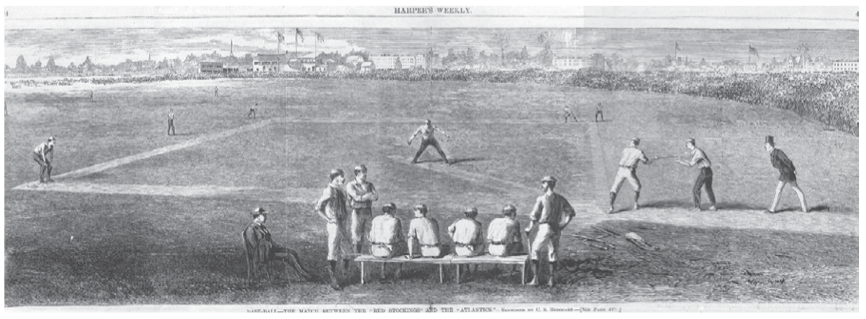

A July 2, 1870 Harpers Weekly illustration of the game.

“Friend Chadwick,” Harry Wright addressed the esteemed baseball authority and sports journalist Henry Chadwick in a pre-season letter updating the condition of Wright’s Red Stockings team. The success of the undefeated Red Stockings in 1869 had sparked national interest in the club’s fortunes. Wright, the captain of the team, was confident his nine, which returned every starter from 1869, would continue to dominate the other top clubs:

“I have the players here now in far better form than they were this time a year ago. They are all members of the gymnasium here, and exercise daily…. I think, when we go East this season we will be able to play a game or games of ball that will keep our reputation.”

The Red Stockings ended the 1869 season undefeated in 57 games. They began 1870 with an extended Southern tour into New Orleans. After defeating several area nines back home in Cincinnati, the winning streak reached 71 games. But the stiffest competition was still in the East and it was there the Red Stockings would run the gauntlet.

As in 1869, the Cincinnati club organized a long road trip, beginning in Cleveland on May 31, and ending with a match in Washington, D.C. on June 28. After defeating the Cleveland boys, they moved through upstate New York and into Massachusetts. The traveling correspondent from the Cincinnati Commercial noted that the famous Red Stockings attracted “great attention in the streets,” and created “much excitement along the route and in the cities.” The Red Stockings arrived in New York on June 12, their winning streak at 80 games.

Not everyone treated them so warmly there. The New York Herald criticized the club for dictating such harsh financial terms that New York clubs were forced to raise ticket prices to a minimum of 50 cents. But the Red Stockings directors believed the New Yorkers would pay. They were right. More than 7,000 turned out the next day to watch Cincinnati easily defeat the elite New York club, the Mutuals, 16–3. After the victory, the papers predicted another unbeaten Eastern tour for the invaders from the West. The next day, the Red Stockings played the Atlantics of Brooklyn, a team they had defeated soundly in 1869, 32–10.

The New York World described the pre-game scene at the Capitoline Grounds in Brooklyn that Tuesday afternoon:

“Little urchins shouted, ‘score cards, names and positions of both nines,’ all the way from Fulton Ferry to Bedford, and all Brooklyn seemed awake to the event of the day. Stores were deserted, boys who could not obtain permission to leave school played hooky, and hundreds who could or would not produce the necessary fifty-cent stamp for admission looked on through cracks in the fence, or even climbed boldly to the top, while others were perched in the topmost limbs of the trees, or on the roofs of surrounding houses.”

By game time between 12,000 and 15,000 spectators were on the grounds, many thousands standing in a semi-circle that stretched deep into the outfield. The Atlantics appeared in their traditional uniform of long dark blue pants and white shirts with an “A” on the front, and the Red Stockings, in their white uniforms and long red hose, tipped their caps as they came onto the field to acknowledge the polite applause of the spectators.

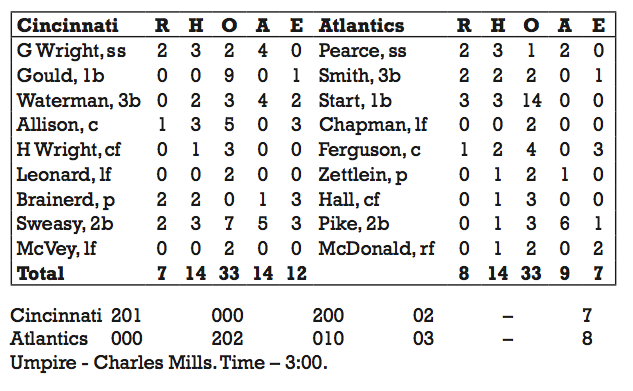

Seven members of the Atlantics were holdovers from the 1869 team; the main addition was George Zettlein, a powerful pitcher the Red Stockings had never faced. The Red Stockings edged out to a 3–0 lead, but sloppy fielding by third baseman Fred Waterman, first baseman Charles Gould and second baseman Charlie Sweasy let the Atlantics take the lead, 4–3, after six innings. In the top of the seventh, George Wright quieted the big crowd with a single that drove in two runs, and the Red Stockings reclaimed the lead, 5–4. The Atlantics tied the score in the eighth, 5–5, and that is where it stood after nine full innings.

Seven members of the Atlantics were holdovers from the 1869 team; the main addition was George Zettlein, a powerful pitcher the Red Stockings had never faced. The Red Stockings edged out to a 3–0 lead, but sloppy fielding by third baseman Fred Waterman, first baseman Charles Gould and second baseman Charlie Sweasy let the Atlantics take the lead, 4–3, after six innings. In the top of the seventh, George Wright quieted the big crowd with a single that drove in two runs, and the Red Stockings reclaimed the lead, 5–4. The Atlantics tied the score in the eighth, 5–5, and that is where it stood after nine full innings.

The rules of the era did not dictate extra innings unless one captain wished the game to continue. Harry Wright could well have taken the tie, and kept the unbeaten string alive, and that is what the umpire and the Atlantics captain Bob Ferguson assumed would happen. The umpire left the field, and Ferguson’s Atlantics headed to their clubhouse. But Harry engaged Ferguson in discussion about continuing. Ferguson seemed content to accept the tie, but Harry persisted. Finally, the umpire was recalled, the players returned, and the game resumed.

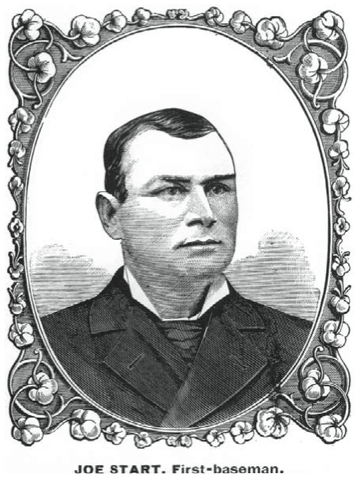

The Red Stockings were out in order in the top of the 10th; the Atlantics mounted a rally in the bottom of the inning. With two on and one out, George Wright moved to catch a short fly ball. But instead he let it bounce, and with no infield fly rule yet written, he easily started a double play. In the 11th, the Red Stockings appeared to have won the game with a two-run rally. But the Red Stockings’ ace pitcher, Asa Brainard, now seemed to tire. With one on and no outs, Joe Start, the Atlantic first baseman, lined a ball far over Cal McVey’s head in right field. The ball rolled into the crowd, where, by most accounts, an exuberant spectator jumped on McVey’s back. McVey shook him off and returned the ball to the infield. One run scored and the batter reached third. The Red Stockings finally got an out, but then Ferguson singled home the tying run, and Zettlein followed with another hit, putting runners on first and second. And then came the play that ended the streak.

George Hall, the Atlantics’ center fielder, bounced a ball to George Wright, a sure double play, but George’s throw sailed by Sweasy, and Ferguson, running hard from second, scored the winning run.

“The yells of the crowd could be heard for blocks around and a majority of the people acted like escaped lunatics,” wrote the New York Sun correspondent. The Red Stockings quickly boarded their omnibus and left the grounds, upset at the loss, but gracious in defeat. No one made an issue of McVey’s tussle with the spectator; the boys understood that the Atlantics had beaten them squarely. If the streak had to end—and surely it did—this was the way it should have happened: hard fought, stirring rallies, lead changes and extra innings. Club President Aaron Champion summed it up in a telegram back to Cincinnati: “The finest game ever played. Our boys did nobly, but fortune was against us. Eleven innings played. Though beaten, not disgraced.”

This essay was originally published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here.

Additional Stats

Brooklyn Atlantics 8

Cincinnati Red Stockings 7

11 innings

Capitoline Grounds

Brooklyn, NY

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.