February 9, 1889: A Wondrous Ball Park: The Pyramid Game in Giza, Egypt

Baseball fans can debate incessantly over what is the greatest game ever played. But there’s no debate concerning the greatest site to host a game. Only one “ballpark” in history can trace its lineage across three millennia, or boast the status of one of the Seven Wonders of the World.

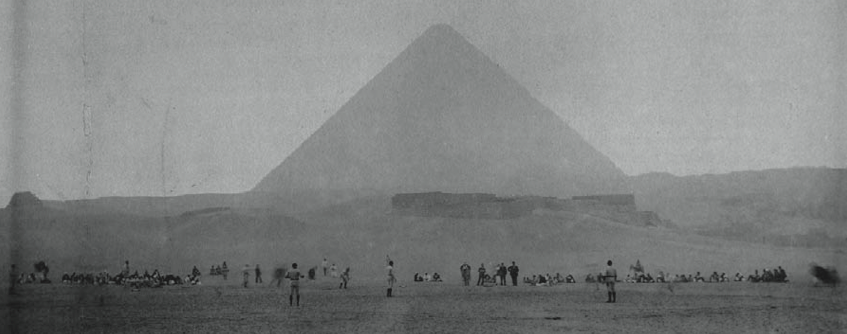

On February 9, 1889, about 20 stars of the National League played ball on the desert sand of the Great Pyramids at Giza, Egypt. The event was the centerpiece of a world tour organized by Chicago White Stockings executive and sporting goods manufacturer Albert G. Spalding in an effort to promote America’s national pastime in foreign locales.

As a business proposition, the event was a bust. In addition to Egypt, the tour visited Hawaii, Australia, New Zealand, India, Italy, France, Scotland, and England, generally attracting small crowds that consisted largely of American tourists. “I consider base ball an excellent game, but cricket a better one,” Britain’s Prince of Wales famously observed after the players’ March exhibition at London’s Kensington Oval.1 Spalding was said to have lost between $30,000 and $40,000 on the venture.2

The tour did succeed, however, as a statement that baseball had come of age as America’s national pastime. Firmly in that belief, the 20 players—10 representing the White Stockings, the rest drawn from other National League teams—had set off the previous October for a trip designed to keep them abroad through March.

Three future Hall of Famers were among the tourists. Adrian C. “Cap” Anson was the first baseman and captain of the White Stockings, John Montgomery Ward played shortstop and Ned Hanlon center field for the All-Americas, as the opponents were called. Two other future Hall of Famers accompanied the group: George Wright as umpire and Henry Chadwick, the era’s best-known baseball writer. Yet another, King Kelly, played on the U.S. portion of the tour, but did not go overseas.

Here are the rosters:

- White Stockings: Mark Baldwin and John Tener, pitchers; Tom Daly, catcher; Cap Anson, first base; Fred Pfeffer, second base; Tommy Burns, third base; Ed Williamson, shortstop; Martin Sullivan, Jimmy Ryan, and Robert Pettit, outfielders.

- All-Americas: John Healy, Indianapolis, and Cannonball Ed Crane, New York, pitchers; Billy Earle, Cincinnati, catcher; G.A. Wood, Philadelphia, first base; Fred Carroll, Pittsburgh, second base; Jimmy Manning, Kansas City, third base; John Montgomery Ward, New York, shortstop; James Fogarty, Philadelphia, Ned Hanlon, Pittsburgh, and Tom Brown, Boston, outfielders.

In the absence of daily communication from overseas, knowledge of the actual play is limited to the accounts furnished by Francis Richter, editor of Sporting Life, one of the two popular baseball weeklies of the era, and Harry Clay Palmer, an author who wrote a book about the trip. If any box score was kept, it no longer exists. The Sporting News, Richter’s archrival in the coverage of baseball-related happenings, scorned the enterprise and ignored the Pyramid Game.

In the absence of daily communication from overseas, knowledge of the actual play is limited to the accounts furnished by Francis Richter, editor of Sporting Life, one of the two popular baseball weeklies of the era, and Harry Clay Palmer, an author who wrote a book about the trip. If any box score was kept, it no longer exists. The Sporting News, Richter’s archrival in the coverage of baseball-related happenings, scorned the enterprise and ignored the Pyramid Game.

The teams arrived in Cairo after a sea passage from Ceylon with the All-Americas holding a 15–13–1 edge in the series. They took up lodgings in the Orient Hotel, and, after an evening to regain their land legs, set out the next morning for the playing site. The transportation was unusual to say the least: The White Stockings were provided donkeys, the All-Americas took camels. The teams switched mounts halfway along. They arrived at 2 p.m., had lunch, posed for photographs, and toured the historic sites before proceeding to what Anson described as “the hard sands of the desert, where a diamond had been laid out.”3

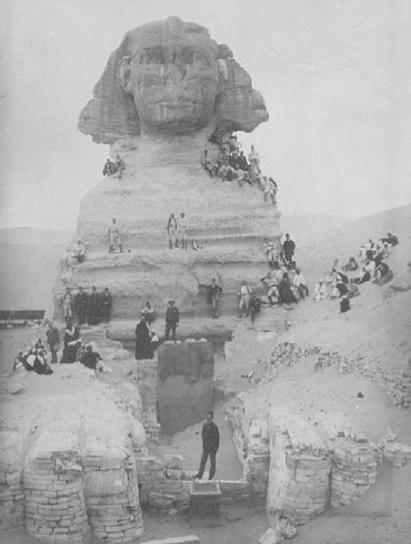

Their audience for the game consisted largely of what Anson referred to as “Arabs”—presumably local Egyptians—with a few tourists thrown in. The Chicagos got away quickly, scoring twice in the first inning off Healy, whose nickname, ironically, was Egyptian. The All-Americas heartily returned fire in the second, swatting Tener around for seven runs and effectively deciding the outcome. From that point on, Daly provided the on-field excitement with a home run in the fourth.4 Spalding, who umpired in Chadwick’s absence, called the game after five innings and declared the All Americas the winner by a score of 10–6. “I apologized to the Sphinx on behalf of my team … to this she turned a deaf ear,” Anson reported.5

The spectators were generally respectful, but puzzled by what was happening before them. In an age when games began and ended with the same ball, fouls hit into the crowd presented a particular difficulty. “When the ball was thrown or batted into the crowd, the Arabs would pounce upon it and examine it as though it were one of the greatest of curiosities, and it was only after a row that we could get it in our possession,” Anson wrote.6

After the game, both teams dallied a while at the site. Observers reported that they amused themselves by throwing baseball’s at the Sphinx’s right eye, and that Fogarty, the Philadelphia outfielder, actually hit it.7

The All-Americas also prevailed during the overall tour, winning 14 of the 28 games contested on foreign soil. The White Stockings won 11 and three ended in a tie.

Although the tour did little to promote baseball around the world, it still had plenty of impact. Since 1885, Ward had been a leader of the Brotherhood Movement, the game’s first players union. While he cavorted with Spalding on the other side of the world, the other National league club owners drew up revised rules that had the effect of reducing the Brotherhood’s impact. Learning of this in Europe, Ward deduced—probably correctly—that he and the players he represented had been taken advantage of. He quit the tour, rushed home, and began to draw plans for what would become the Brotherhood War of 1890.

Notes

1 Spalding, Albert G. America’s National Game (New York: American Sports Publishing Company, 1911).

2 “Just Like Emigrants,” The Sporting News, March 9, 1889, p. 1.

3 Anson, Adrian C. A Ball Player’s Career (Mattituck, N.Y., Amereon House, 1900).

4 Lamster, Mark. Spalding’s World Tour (New York: Perseus Books, 2006).

5 Anson, A Ball Player’s Career.

6 Anson, A Ball Player’s Career.

7 Anson, A Ball Player’s Career.

Additional Stats

All-Americas 10

Chicago White Stockings 6

Giza, Egypt

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.