July 14, 1887: The color line is drawn in baseball

On the morning of July 15, 1887, the New York Herald boldly titled one of its front-page stories, “THE COLOR LINE.” The story under the headline, from New Orleans, involved a claim by former Union Army “negro soldiers” that they were being denied admission into the local post of the Grand Army of the Republic, a veterans organization, solely on account of color. The “negro Union veterans” complained that “the local posts of the G.A.R. prefer to fraternize with the ex-Confederate organizations … rather than with their colored ex-comrades.”1 Higher-ups in the G.A.R. offered not the slightest apology.

On the morning of July 15, 1887, the New York Herald boldly titled one of its front-page stories, “THE COLOR LINE.” The story under the headline, from New Orleans, involved a claim by former Union Army “negro soldiers” that they were being denied admission into the local post of the Grand Army of the Republic, a veterans organization, solely on account of color. The “negro Union veterans” complained that “the local posts of the G.A.R. prefer to fraternize with the ex-Confederate organizations … rather than with their colored ex-comrades.”1 Higher-ups in the G.A.R. offered not the slightest apology.

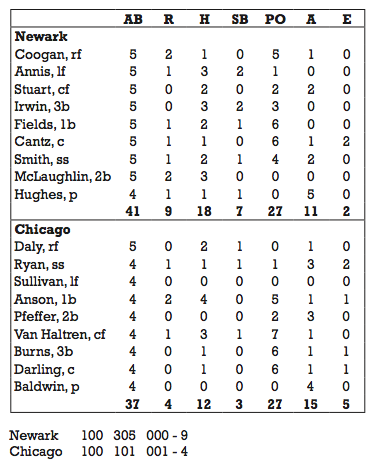

Meanwhile, on the sports page, the Herald reported that Newark of the International League had defeated the Chicago White Stockings, the reigning National League champion, 9–4. The brief report said, in part, “The home club hit Mark Baldwin very hard, but the visitors were not so fortunate with Mickey Hughes .” Newark had 18 hits and two errors while Chicago had 12 hits and five errors. The account noted that the batteries consisted of Hughes and Bart Cantz for Newark and Baldwin and Dell Darling for Chicago.2

The real story of this day, however, was what was not reported — events that would change the face of baseball for the next 60 years.

Chicago and Newark played because the White Stockings had an off day after completing a series in Washington. The White Stockings were to start a series with the Giants in New York on the 15th. This gave Chicago a lucrative opportunity for an exhibition game on the 14th at the Newark ballpark.

Newark had a powerful team that had won the Eastern League championship the preceding season and had jumped out to a strong start in its first year in the International League. The team’s ownership correctly anticipated that fans would come to the ballpark in droves to see the White Stockings. The Newark fans were confident; after all, they had one of the best batteries in minor-league baseball. Twenty-one-year-old left-handed pitcher George Stovey began the season by capturing his first 10 decisions, and Moses Fleetwood Walker was one of the better defensive catchers in the International League. Both were men of color.

A story in the Newark Evening News provided some information that the Herald’s story lacked. In a frontpage article headlined “DRAWING THE COLOR LINE; Chicago Unwilling to Play With Stovey, No More Colored Players,” the Evening News reported fully on what happened in Newark as well as at an International League meeting in Buffalo that day.

“Before the game with the Chicago Club yesterday, Manager Charles Hackett (of Newark) received a telegram from Captain Cap Anson (of Chicago) saying that the Chicago Club would not play if Stovey and Walker, the colored men, were put at the points,” the newspaper reported. It said Hackett “would probably have had Stovey pitch, however, but for the fact that that player was not feeling well, so Hughes was substituted at the last moment.” No explanation was offered for why Walker was also not played.

The report then shifted to the upstate New York meeting: “The International League representatives held a meeting at the Genesee House, in Buffalo, yesterday and passed a resolution instructing Secretary (C.D.) White not to approve the contract of any more colored players. Jersey City and some of the other clubs insisted the African players drove white men from the league.”3

A biography of Stovey by Brian McKenna of the Society for American Baseball Research sheds additional insight on the matter. According to the biography, the Newark Sunday Call effectively dismissed the Stovey “not feeling well” report and offered this version: “It was announced on the (grounds) that he was sulking, but it has since been given out that Anson objected to a colored man playing.”4

McKenna’s research on Stovey’s life amplified what else may have driven the banning of further contracts with “colored players” at the International League meeting in Buffalo. The vote, he says, “was sparked by a revolt in the Binghamton club” against two black Binghamton players, Bud Fowler and William Renfro. He added: “After the contest on June 27, one of Binghamton’s white players, Buck West , rallied the rest of the team around his cause. A petition was signed by nine players and a telegram was sent to the club directors demanding that Fowler and Renfro be released or the protesters would strike.5

With the Binghamton players’ petition looming and Anson’s chilling financial threat to withdraw his popular White Stockings from play with clubs fielding “colored players,” it was probably a relatively easy step for the International League team representatives to pass the ban. McKenna’s research, however, adds another layer to the story.

The Newark and Jersey City teams had joined the International League in 1887 after playing in the Eastern League the season before. In 1886 Pat Powers , owner of the Jersey City team, had signed Stovey from the all African American Cuban Giants, “and Stovey had pitched exceedingly well in ’86 for Jersey City; 270 IP, 1.13 ERA and 203/43 SO/BB ratio.” But after the season Powers lost a contract dispute that involved Stovey jumping to Newark. “Powers had little motive to save Stovey from being banned and perhaps all the motive in the world to see him excluded from IL play,” McKenna wrote.

Stovey and Walker remained with Newark until season’s end, Stovey’s 2.42 ERA ranking sixth among 32 International League pitchers for the year. Stovey remained active in minor league and semiprofessional baseball as a player and umpire for a good number of years. Walker remained in the International League through 1889 despite the ban.

At the same time, on the day that Stovey was withdrawn, Organized Baseball effectively committed to a policy to exclude “colored players.” The prohibition remained in effect for six decades until it was breeched by Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey .

This essay was originally published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here .

Notes

1 New York Herald, July 15, 1887, p. 1.

2 Ibid. p 9.

3 Newark Evening Journal, July 15, 1887, p.1.

4 Newark Sunday Call, July 17, 1887, cited by Brian McKenna, in “George Stovey”, SABR BioProject, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/8ff10f5c .

5 McKenna, Ibid.

Additional Stats

Newark Little Giants 9

Chicago White Stockings 4

Newark Base Ball Grounds

Newark, NJ

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.