June 19, 1897: Wee Willie Keeler’s 44-game hitting streak ends

Presumably due to his size, William Henry “Wee Willie” Keeler had a hard time convincing managers he could play the rough-and-tumble game in vogue in the 1890s. The New York Giants gave the 5-foot-4, 145-pound Brooklyn-born 21-year-old just 77 at-bats in 1892 and 1893. They were not persuaded by his .325 batting average and cut him loose. Keeler caught on with Brooklyn for 20 games, batting .313, good enough to make him a throw-in on a deal designed to unload aging veteran Dan Brouthers to Baltimore in return for journeyman Billy Shindle and coveted young outfielder George Treadway.

Presumably due to his size, William Henry “Wee Willie” Keeler had a hard time convincing managers he could play the rough-and-tumble game in vogue in the 1890s. The New York Giants gave the 5-foot-4, 145-pound Brooklyn-born 21-year-old just 77 at-bats in 1892 and 1893. They were not persuaded by his .325 batting average and cut him loose. Keeler caught on with Brooklyn for 20 games, batting .313, good enough to make him a throw-in on a deal designed to unload aging veteran Dan Brouthers to Baltimore in return for journeyman Billy Shindle and coveted young outfielder George Treadway.

In Baltimore Keeler fell in with the one gang that could see beyond his physical limitations. Beyond the 6-foot-2, 200-pound Brouthers, the undersized Oriole team being assembled by Ned Hanlon cared far more about brains and hustle than bulk. John McGraw and Heinie Reitz stood just 5-foot-7; Hughie Jennings and portly Wilbert Robinson barely reached 5-foot-8 and even slugging outfielders Joe Kelley and Steve Brodie failed to top six feet.

That absence of size failed to slow the Orioles, who more than made up for it with a slashing, inventive style of ball designed to take advantage of every available physical, mental, and emotional edge. From 1894 through 1896, the Orioles slashed their way to three consecutive National League championships. They did it with their bats; the Orioles averaged about .332 over the three-year span. They did it with their feet, averaging more than 350 steals per season over their championship run. When necessary, they did it with their bodies. Orioles batters were hit by pitched balls 324 times between 1894 and 1896, 133 times more than the team that ranked second over that time span.

The Orioles also did it with their brains. They spent more time than any other team devising strategies to take advantage of, and sometimes circumvent, the rules. Finally, they did it with their mouths. They were unapologetic in their desire to intimidate. “Baseball as she is played,” Hanlon explained of the approach, whose elements included distracting batters, blocking runners, upending fielders, and baiting umpires.

Keeler was never much for the umpire-baiting, but in all other respects he was the focus of the Oriole offense. A superb contact hitter before the phrase was invented, he specialized in slapping the ball to precise areas of the outfield. This precision, which Keeler explained as an effort to “hit ’em where they ain’t,” made him virtually impossible to retire easily. Between his first full season in 1894 and 1904 Wee Willie made fair contact in 98.6 percent of his official at-bats. Through 1906, he never batted below .313 and won two batting titles. Keeler topped .360 annually between 1894 and 1900.

It was in 1897 that Keeler attained his greatest batting glory. He singled and doubled in the season opener against Boston, had at least two hits in eight of the Orioles’ first nine games, and by the end of the first week of June had collected 70 hits. His average stood at .446.

To that point the closest any pitcher had come to stopping Keeler was St. Louis left-hander Duke Esper, who held him to a bunt single on June 5. The bunt extended Keeler’s consecutive-game hitting streak for the season to 35.1 He ran it to 40 against Louisville a week later, and on June 16 hit safely in his 43rd consecutive game, breaking the record set by Bill Dahlen of the Chicago Colts three seasons earlier.2 On June 18 he thrashed Pink Hawley of Pittsburgh for a single, double, and triple.

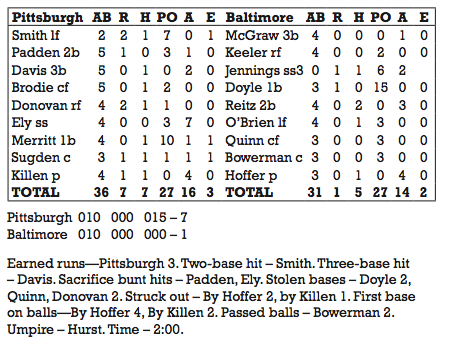

Left-hander Frank Killen pitched for Pittsburgh on June 19, hoping both to stop Keeler and to atone for his own poor performance of three days earlier, when he left after less than one inning of work. He did more than that, holding the Orioles to just five hits, all of them singles. Meanwhile, two late and costly errors by Orioles shortstop Jennings permitted four unearned runs to score in the eighth and ninth innings. The final score was 7–1.

Keeler faced Killen four times, and never got a good piece of him. His closest brush with a hit occurred in the third when he ticked a weak ground ball toward third and lit out for first base. He wasn’t fast enough; Harry Davis raced in, grabbed the roller, and threw to first just in time to record the out. When Keeler was retired twice more on routine plays, the longest batting streak in the game’s history had been ended. The streak remained in the record book for more than four decades, until Joe DiMaggio erased it on the way to his 56-game streak of 1941.

Keeler and Killen met once more in 1897, that coming in the first game of a doubleheader on September 6 in Baltimore. Willie went 3-for-5. His season-ending .424 average won the league’s batting title by 34 points.

Notes

1 That total did not include the final game of the 1896 season, in which he also had hit safely.

2 Some historians credit Denny Lyons, playing for the Athletics of the American Association, with a 52-game hitting streak in 1887. That streak is not officially recognized, however, because it included games in which Lyons reached base only via walks—which were counted as hits in 1887.

Additional Stats

Pittsburgh Pirates 7

Baltimore Orioles 1

Union Grounds

Baltimore, MD

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.