May 12, 1890: The Kid, the Bolt, and Silent Mike

In 1890 the Players League sat on top of the baseball world, such as it was. Perhaps nowhere else was this more apparent than in New York City, where the Giants of the National League played second fiddle to another team composed almost exclusively of their former players, who complicated the situation further by also calling themselves the Giants. The Players League Giants scheduled games in direct conflict with the original Giants and built Brotherhood Park next to their former club’s home field, the New Polo Grounds.

The National League Giants, who became the first team to win consecutive undisputed “World’s Championships” in 1888–89, were decimated for 1890 when practically all of their star players jumped to the Players League. The only first-string players to remain were pitcher Mickey Welch, a future Hall of Famer, and Silent Mike Tiernan, a hard-hitting outfielder.

The National League Giants, who became the first team to win consecutive undisputed “World’s Championships” in 1888–89, were decimated for 1890 when practically all of their star players jumped to the Players League. The only first-string players to remain were pitcher Mickey Welch, a future Hall of Famer, and Silent Mike Tiernan, a hard-hitting outfielder.

The Players League Giants consistently outdrew their National League counterparts. This was the situation on Monday, May 12, 1890, when only 687 cranks[fn]“Over The Fence In Centre Field,” New York Herald, May 13, 1890, p.8.[/fn] showed up for the National League Giants- Boston game, while 1,707[fn]2. Ibid.[/fn]patrons attended the Players League Giants-Boston game next door.

National League teams went to great lengths to obtain star players. The Giants managed to convince the Indianapolis team’s owner, John Brush, that the 18-year-old pitching phenomenon Amos “The Hoosier Thunderbolt” Rusie was more valuable to the National League’s success playing his home games in New York City than in Indiana. Thus, Rusie came to the National League Giants, where he would go on to a Hall of Fame career with more than 20 victories in each of the next eight seasons.

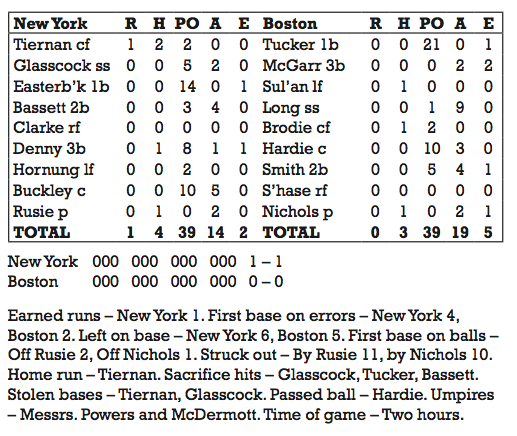

To say that Rusie, now only in his second majorleague season, was the backbone of the Giants pitching staff in 1890 is an understatement. He pitched in a career-high 67 games. He managed 29 wins against 34 losses for an anemic-hitting team and completed 56 of the 62 games he started, including four shutouts.[fn]John Thorn, Phil Birnbaum, and Bill Deane, eds. Total Baseball: The Ultimate Baseball Encyclopedia, 8th Ed. (Toronto: Sport Media Publishing, Inc.)[/fn] That day’s starting pitcher for the National League Boston Beaneaters, 20-year-old rookie Kid Nichols, would go on to have a 27–19 season, appearing in 48 games and completing all of his 47 starts while pitching a league-leading seven shutouts.[fn]Thorn et. al., op. cit.[/fn] Nichols would be one of only three pitchers of the 1890s (Rusie and Cy Young were the others) inducted into the Hall of Fame, leading that decade with seven seasons of 30 wins or better.

“Silent” Mike Tiernan arrived with the National League Giants as a rookie in 1887 and played an integral part as the starting right fielder for the club’s back-to-back world’s championships. Tiernan hit home runs in double digits five times, leading the league in 1890 and 1891 with 13 and 16 respectively. His .311 lifetime batting average for his 13-year career,[fn]Ibid.[/fn] all with the Giants, made him a New York fan favorite. His nickname was attributed to his disinclination to argue with umpires in an era when the reverse was the norm.

The home-team National League Giants elected to bat first, hoping to get first crack at the still lively ball. In the bottom of the first inning, Boston stranded its lead runner at third base, the only Beaneater to reach third in the game. The pitching duel continued for 12 innings with remarkable defensive play by both teams, particularly by Herman Long, Boston’s great shortstop. Nichols struck out 11 (New York Herald) or 10 (New York Times), while Rusie fanned 12 (Herald) or 11 (Times).[fn]“Tiernan’s Home Run Won It,” New York Times, May 13, 1890, p.3.[/fn]

As the game passed beyond the ninth inning, each putout by the Giants was met with lusty cheers by the small but enthusiastic crowd. This brought many of the spectators in the adjacent Brotherhood Park to the top row of the grandstand that overlooked right field and center field of the New Polo Grounds.[fn]New York Herald, op. cit., loc. cit.[/fn] Soon, every putout was met with cheering from both parks. Nichols struck out Rusie to start the top of the 13th, and with the game in Brotherhood Park a 12–2 Boston rout, the attention of almost all at that game turned to the National League contest.

The next batter after Rusie was Tiernan, who had one of the three hits that Nichols had allowed. (Rusie had also allowed only three.) Tiernan fouled off the first pitch into the grandstand. Before the foul ball could be retrieved, the Giants quickly provided a brand-new ball to the umpire, who tossed it to Nichols. Nearly simultaneously, the ball that Tiernan fouled off was thrown back to Nichols’ feet. Remembering that Tiernan’s only other hit in the game, back in the eighth inning, had been off a new ball, Nichols picked up the old ball and asked the umpire, “This ball is all right, isn’t it?” “No, the new ball was on the field first,” said umpire Phil Powers, “and you will have to use it.”[fn]Ibid.[/fn]

The significance of the new ball was not missed by the cranks, who chanted, “Now, Mike.” Nichols’ very next pitch was shoulder high and the sound of Tiernan’s bat communicated that every pound of his power was behind it. The ball headed for the deepest part of the outfield, more of a line drive than a towering shot. Center field in the New Polo Grounds had been set at 360 feet when the ballpark was hastily built during the start of the 1889 season,[fn]Lowry, Philip J. Green Cathedrals (Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., 1992), p.190.[/fn] but the distance had been increased by 50 feet before play began in 1890.[fn]New York Herald, op. cit., loc. cit.[/fn] Additionally, a canvas-covered wooden fence sat atop a tall, steep embankment. Tiernan’s blow cleared the center-field fence near the flagpole, landed in the narrow alley between the two stadiums and bounded against the wall of Brotherhood Park. The onlookers in both parks erupted in wild cheering as Tiernan circled the bases. Rusie then made quick work of Boston in the bottom of the 13th.[fn]Ibid.[/fn]

One sportswriter predicted that the flagpole would long mark the spot of Tiernan’s great hit. But when the Players League disbanded, the National League Giants took over Brotherhood Park, renaming it the Polo Grounds. The site of the great game of May 12, 1890, passed into obscurity.

This essay was originally published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here.

Additional Stats

New York Giants 1

Boston Beaneaters 0

13 innings

Polo Grounds

New York, NY

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.