September 23, 1908: Giants, Cubs play to disputed tie in ‘Merkle Game’

The National Football League (NFL) is replete with famous games that have titles attached to them. Every serious football fan knows that the 1958 NFL championship match between the New York Giants and the Baltimore Colts became known as “The Greatest Game Ever Played,” and that the 1974 playoff tilt between the Oakland Raiders and the Miami Dolphins lives on as “The Sea of Hands Game.”

The National Football League (NFL) is replete with famous games that have titles attached to them. Every serious football fan knows that the 1958 NFL championship match between the New York Giants and the Baltimore Colts became known as “The Greatest Game Ever Played,” and that the 1974 playoff tilt between the Oakland Raiders and the Miami Dolphins lives on as “The Sea of Hands Game.”

Baseball history, on the other hand, gives titles to moments of glory or ineptitude rather than whole games. The third game of the 1951 playoff between the New York Giants and the Brooklyn Dodgers is known for Bobby Thomson’s “Shot Heard ‘Round the World,” and there was the famous “Snodgrass Muff,” a fly ball dropped by Fred Snodgrass of the Giants in the final game of the 1912 World Series.

The New York Giants had a long history of famous games and moments. One of the earliest occurred on September 23, 1908 at the Polo Grounds and it has gone down in baseball lore as “Merkle’s Boner.”

It’s obvious that this took place a long time ago because it happened in the middle of a pennant race involving the Chicago Cubs. Here’s the scenario. By September that year, the Giants, Cubs, and Pittsburg Pirates were involved in a pennant race so tight that any of the three could be in first place on one day and third place the next.1 On September 23, the Giants (87-50) and the Cubs (90-53) were in a dead heat with the Pirates (89-54) one game back. On that date the Giants and Cubs met in the third game of a crucial four-game series at the Polo Grounds. The Cubs had swept a doubleheader the previous day, winning 4-3 and 3-1.

Jack Pfiester, who went 12-10 with a 2.00 earned-run average that year, started for the Cubs, while Hall of Famer Christy Mathewson, who would finish the season at 37-11 with a 1.43 ERA, went to the hill for New York. The game was scoreless until the top of the fifth, when Joe Tinker hit a home run off Mathewson to put the Cubs up 1-0.2 The Giants tied the game in the sixth, on a single by right-fielder Mike Donlin that scored second baseman Buck Herzog. Neither team scored in the seventh or eighth, or the top of the ninth for that matter. The Giants took their turn in the bottom of the inning with a chance to win the game and take a one-game lead on the Cubs.

Center-fielder Cy Seymour led off by grounding out to Johnny Evers at second. Third baseman Art Devlin followed with a single. With one out and one on, perhaps the most critical play of the game occurred when left fielder Elwood “Moose” McCormick hit a grounder to Evers that had double play written all over it. Evers tossed to Tinker, forcing Devlin at second, but in a hard-nosed move that probably brought a tear to the eye of Giants manager John McGraw, Devlin slid hard into second, preventing Tinker from completing the double play.

Fred Merkle was up next. It should be noted here that Merkle was a 19-year-old rookie at the time; he appeared in 15 games in 1907 and had only 41 at-bats in all of 1908. This game marked his first start in the major leagues and it only occurred because regular first baseman Fred Tenney woke up that morning with a case of lumbago.

As he entered the batter’s box, Merkle had gone 0-for-2 with a walk. With two strikes on him, Merkle smacked Pfiester’s third pitch down the right-field line for a single, allowing McCormick to run all the way to third. Shortstop Al Bridwell was up next. Pfiester threw; Bridwell swung and hit a line drive up the middle. McCormick scored from third and Merkle, on his way to second, stopped running before he reached second. The rest, as they say, was pandemonium.

Merkle’s action was understandable. Fans were allowed onto the field after games at the Polo Grounds, and team locker rooms were out in center field. To get to the clubhouse, a player would have to run past the fans, many of whom wanted to talk to or congratulate the players – if the team won. It was common practice in that type of situation for a player to forego the formality of touching the base he was running to and start hightailing it to the showers.

While that may have been the custom, it isn’t the rule. Rule 4.09 says that a run shall not count if the runner advances to home when the third out is made by a force play, in this case, at second. Evers knew that and even though fans were all over the field, he shouted at Cubs center-fielder Solly Hofman to throw him the ball so he could touch the bag for the force play on Merkle, thus negating the run. What actually happened next is impossible to say with certainty because accounts varied and no video evidence exists of the event. This explanation is as good as any:

“Once it [the ball] was thrown in, it might have been intercepted by Giants pitcher Joe (Iron Man) McGinnity, who was coaching third base that day, and McGinnity might have lost it to charging Cubs players or thrown it into the stands, where the Cubs retrieved it, possibly by decking a fan in a bowler hat,” wrote Tim Layden in Sports Illustrated. “Then again, the recovered ball might not have been the one that Bridwell struck.”3

At any rate, Evers grabbed somebody’s ball and touched second, setting off an argument amidst rioting fans in which the Cubs claimed that Merkle was out. The two umpires needed to make a decision and required police protection to get to an area under the grandstand to consult. Second-base umpire Bob Emslie had fallen down to avoid getting hit by Bridwell’s smash, and so didn’t see anything. The call was home plate umpire Hank O’Day’s to make, and he called Merkle out.

Most people don’t realize that O’Day and the Cubs were involved in this type of situation just a few weeks earlier. On September 4, the Cubs were playing the Pirates when Pittsburg rookie Warren Gill didn’t touch second base when a run scored. O’Day was umpiring on his own that day and was watching the runner from third cross the plate when Evers got the ball and touched second. O’Day told Evers he didn’t see the play at second, so he couldn’t call it. The Cubs made a formal protest but National League president Harry Pulliam upheld O’Day’s call.

Calling Merkle out should have ended the inning, and the game should have continued. But it was getting dark and the field was full of ornery fans, so the umpires called the game on account of darkness and declared the game a tie. Pulliam, who was at the game, upheld their decision. It would be replayed in its entirety at the end of the season if it were needed to decide the pennant winner.

It is incorrect to say that this game cost the Giants the pennant. In fact, the two teams met the next day, with the Giants winning 5-4 and taking a one-game lead over the Cubs. McGraw’s men just couldn’t pull away from the Cubs, despite winning 11 of their last 16 games, and, when the season ended on October 7, the two teams were tied atop the standings. They met again on October 8 at the Polo Grounds, with the Cubs winning 4-2 to take the pennant and to go on and defeat the Detroit Tigers in the World Series.

The saddest part of the game was its effect on Merkle. He went on to have a highly respectable 16-year major league career and had a lifetime .273 batting average. He played in five World Series, although he was on the losing side each time. Neither McGraw nor his teammates blamed him for what happened, and they considered him a highly intelligent player. Nonetheless, he got stuck with the nickname “Bonehead,” a sobriquet that followed him for years. He was managing a minor-league team in 1929 and quit abruptly when somebody called him the name. He ended his association with baseball permanently in 1936 when some unnamed minor leaguer “used the ‘B’ word,” while Merkle was umpiring an exhibition game between the bushers and the Washington Senators.4

After 14 years away from the game, Merkle surprised his family in 1950 by accepting an invitation to an Old Timer’s Day at the Polo Grounds. When he was introduced, the fans gave him a loud ovation.

“Merkle and the fans made peace with one another,” wrote Keith Olbermann. “The pain was relieved, the blame absolved.”5

- Related link: Read the SABR Deadball Era Committee’s 100th anniversary newsletter on the ‘Merkle Game’ in 2008

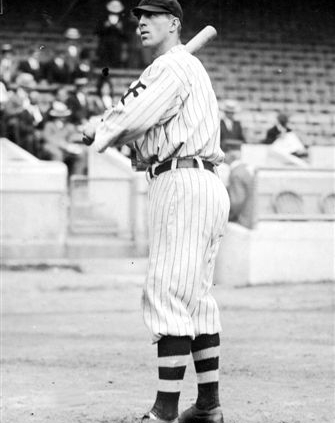

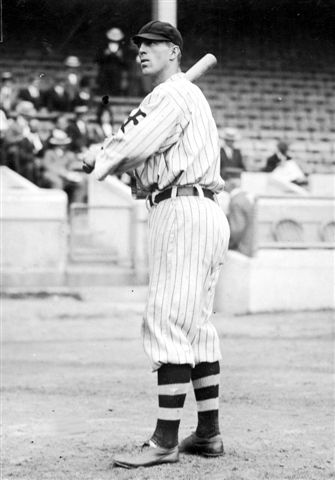

Photo credit

Fred Merkle, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Notes

1 In 1891, the U.S, Board of Geographic Names eliminated the “h” from all American localities that had “burgh” at the end of their names. Pittsburgh got its “h” back in 1911.

2 Tinker hit six home runs that season, good enough for fourth place among National League home-run leaders.

3 Layden, Tim, “Tinkers to Evers to Chance… … to Me,” Sports Illustrated , December 3, 2012.

4 Murphy, Cait, Crazy ’08: How a Cast of Cranks, Rogues, Boneheads and Magnates Created the Greatest Year in Baseball History (New York: HarperCollins, 2007), 295.

5 Olbermann, Keith, “The Goof That Changed the Game,” Sports Illustrated , September 29, 2008.

Additional Stats

Chicago Cubs 1

New York Giants 1

Polo Grounds

New York, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.