‘Little League Home Runs’ in MLB History: The Denouement

This article was written by Chuck Hildebrandt

This article was published in Spring 2017 Baseball Research Journal

At the SABR 45 convention held in Chicago in 2015, I presented a topic that had not previously been studied under the auspices of the Society for American Baseball Research: “Little League Home Runs in MLB History.”1 A “Little League Home Run” (LLHR) is a play that occurs when a hitter puts a ball into play that, under normal circumstances, should result in a routine out or routine base hit, or a runner-on-error event such as reaching first on an overthrow, or taking an extra base on a bobbled ball by a fielder. But instead, the play takes on a life of its own as the fielders boot the ball and throw it around the field, committing multiple errors while the batter-runner — and all the runners before him — circle the bases and score, all the while laughing along with the laughing fans.

-

Related link: Click here to access the SABR Little League Home Runs Database

-

Appendix: Click here to read “Fun Facts About Little League Home Runs”

The presentation was fun to put together, and it must have been fun to watch, too, because SABR bestowed the Doug Pappas Research Award on me for it.2 Also included was a nice check for $250, presumably for the purpose of funding further research into the phenomenon of Little League Home Runs. (Most of the cash award was, in fact, spent in the bar of the Palmer House Hotel while talking about the presentation with other SABRites.)

But I’m not writing this denouement merely to crow about my presentation or my award (or my drinking in fancy hotel bars). I’m writing it to share what happened after the convention that helped finalize the definition of the LLHR, as well as publish an updated list of all known and confirmed LLHRs as of the date of publication of this article, along with some fun facts and general observations about them.

RETHINKING THE DEFINITION OF A LITTLE LEAGUE HOME RUN

Because I received such positive feedback about the presentation, I hoped the idea could earn a feature write-up on a website targeted to baseball fans. Fortunately, FanGraphs agreed and allowed me to repurpose the presentation into a three-part article, complete with embedded video and audio of actual LLHRs, which was published later that summer.

Part I established the proposed definition of the LLHR.3 As in the presentation, to be considered a LLHR the play needed to include the following elements:

-

Two or more errors on the play.

-

Batter scores on the play.

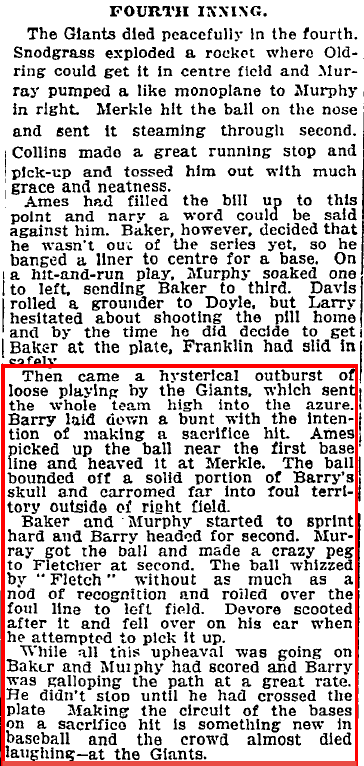

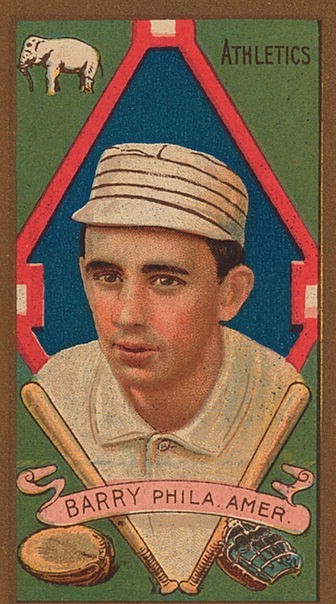

That was it. Simple, right? And the definition had to be simple since we needed to be able to query the play-by-play database maintained by Retrosheet — the universally acknowledged gold standard for the cataloguing of major league games throughout history — to uncover LLHRs for which we have no available video or audio evidence.4 Querying on this proposed definition, the earliest instance of a LLHR in recorded history we could find (as of date of publication) occurred during the fourth inning of Game 6 of the 1911 World Series (nearly 28 years before the actual Little League organization itself was founded and available to lend its name to such a play).5

The inaugural LLHR was hit by Jack Barry of the Philadelphia Athletics against the temporarily hapless New York Giants, and was served up by starter Red Ames. There is a hilarious description of the play that appeared in the New York Times the following day (click the image at right to read it.) It includes such classic lines as, “Then came a hysterical outburst of loose play by the Giants …” and “Making the circuit of the bases on a sacrifice hit is something new in baseball and the crowd almost died laughing — at the Giants.”

The inaugural LLHR was hit by Jack Barry of the Philadelphia Athletics against the temporarily hapless New York Giants, and was served up by starter Red Ames. There is a hilarious description of the play that appeared in the New York Times the following day (click the image at right to read it.) It includes such classic lines as, “Then came a hysterical outburst of loose play by the Giants …” and “Making the circuit of the bases on a sacrifice hit is something new in baseball and the crowd almost died laughing — at the Giants.”

Ain’t 1911 sportswriting grand?

Part II of the article focused on the statistics and oddities peripheral to the phenomenon of the Little League Home Run.6 At the time of the original presentation, of the 148,390 total games available to query in the Retrosheet database (through the end of the 2014 season Figure is from a Retrosheet query provided by David W. Smith, founder of Retrosheet, in an email to the author, August 4, 2015. ), a total of 258 Little League Home Runs had been identified, which worked out to 1.74 LLHRs per 1,000 games played. (Additional and updated information about LLHRs appears in the Appendix.)

Part III was, to my thinking, the most interesting of all, and which did not appear in the original presentation at SABR 45 because of time constraints.7 This final part called the entire premise of Part I into question by examining the original proposed definition and inviting online discussion among the article’s readers as to whether it should remain the proper definition, or whether it should be adjusted.

Also included in Part III were several videos of plays which might have been considered by many — including the TV and radio announcers calling those game — to be LLHRs, but which did not fit the definition as originally proposed. A clear example was a booming hit by the Cubs’ Kris Bryant against the Pirates’ Arquimedes Caminero, early in 2015, that one-hopped the wall for a double.8 Bryant took third on the relay throw to the plate, intended to nab the lead runner, which bounced away from the catcher. As Bryant took a wide turn around third and put the brakes on, the catcher saw the opportunity to put Bryant out and threw to third. At that point, Bryant committed to the plate; the third baseman took the throw and threw back to the catcher, who dropped the ball, and Bryant plated the run.

The Cubs’ TV announcer called this play a Little League Home Run right away. However, the play did not meet our original definition either technically (only one error was made on the play) or aesthetically (Bryant had hit a booming drive over the center fielder’s head, which in an actual Little League game without fences would have allowed the batter to easily trot around the bases for a real live home run).

This specific play notwithstanding, it became clear that there could be many potential batter-scoring plays which might not satisfy the technical definition originally proposed, but which might fairly still be called a Little League Home Run if it could meet the premise of the play in spirit: an ordinary ball put into play that a bunch of kids in the field boot around and throw all over the place, turning what would normally be a routine out or hit into a four-base romp teeming with hilarity.

THE LLHR POLL AND THE RESULTS

The close of Part III included an online survey asking readers of the article to vote on what should or should not qualify as a Little League Home Run.9 Of the eight questions asked, the first seven included video of a play, a written description of the play in case the video did not properly load for the survey taker, and the simple question: “Should this be considered a LLHR?” The available answers were “yes” or “no” with a text box for optional comments. The eighth question consisted of twenty short play descriptions, each with a yes/no radio button for voting, and a comment box for the question overall.

During the seven weeks the survey was open following the publishing of the FanGraphs article, 424 total responses were received, with 642 comments offered by respondents to flesh out their answers.

The first question (see screenshot at right), contained an example of an obvious LLHR which was intended to test the integrity of the answers. It was also the first LLHR shown in both the SABR 45 presentation and the Fangraphs article: Miguel Cabrera’s 2012 “shot” against Colorado.10 Result: 414 of the 424 respondents, almost 98 percent, agreed that this should be a LLHR, with one respondent declaring, “That’s as little league as a little league home run gets.” Another wrote, “Rounding the bases on a grounder to the pitcher is the epitome of a LLHR” and a third chimed in with, “[This example] strikes me as something akin to the platonic ideal of a [Little League] home run.”

The first question (see screenshot at right), contained an example of an obvious LLHR which was intended to test the integrity of the answers. It was also the first LLHR shown in both the SABR 45 presentation and the Fangraphs article: Miguel Cabrera’s 2012 “shot” against Colorado.10 Result: 414 of the 424 respondents, almost 98 percent, agreed that this should be a LLHR, with one respondent declaring, “That’s as little league as a little league home run gets.” Another wrote, “Rounding the bases on a grounder to the pitcher is the epitome of a LLHR” and a third chimed in with, “[This example] strikes me as something akin to the platonic ideal of a [Little League] home run.”

Perhaps the best summarizing comment was, “If this doesn’t fit the definition of a LLHR, I don’t know what does.” The earnestness of the answers to this first question indicated that the respondent base was prepared to take the survey seriously, inspiring confidence in their guidance. (Humorously, though, one of the ten dissenters insisted that all Little League Home Runs “[need] to be hit into the outfield” to qualify, an opinion that also informed the remainder of his answers.)

Most of the six remaining video questions yielded clear majorities one way or the other, all in the direction of the original definition. The voting on one play, however, ran so close that mathematicians might consider it a statistical dead heat. One 2011 play saw the Angels’ Peter Bourjos lining a sharp single into left field that skipped off the glove of a charging Rangers’ David Murphy and scooted all the way to the wall.11 Murphy bolted after the ball, picked it up near the outfield wall and hurled it in, far too late to get the speedy Bourjos.

Even though the play involved only a single defender, a full 49.6% thought this play should qualify as a LLHR. There were plenty of reasonable comments on both sides of the question. Some who thought it should qualify as a LLHR noted that “turning around to chase a ball that a fielder cleanly whiffed on collecting is quintessentially Little League,” and “these are the kinds of plays that happen in Little League all the time.” Those against the LLHR label for the play provided comments such as “feels like LLHR needs at least ONE bad throw (preferably two) to qualify” and that the play “lacks the Keystone Kops factor.”

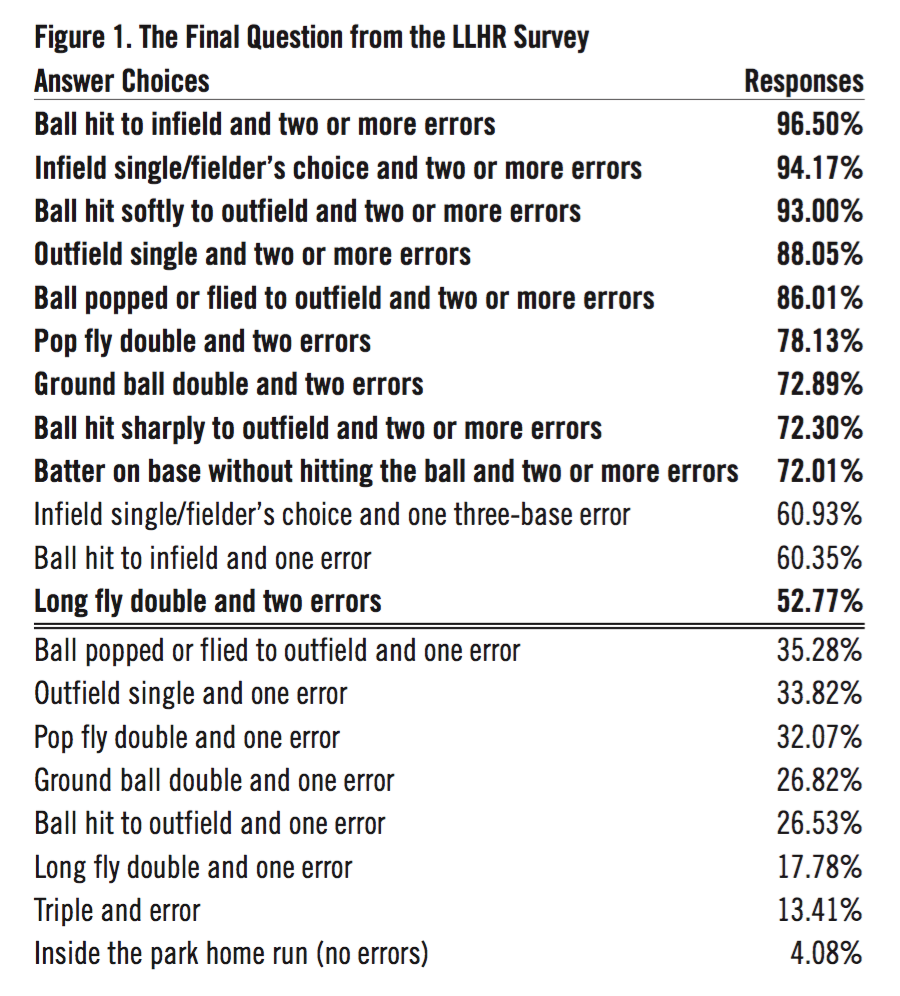

The final question was perhaps the most important one, which could be asked only after respondents had seen the several video examples before it. The intention was to help crystallize in the respondent’s mind what a LLHR should look like in theory, and then to consider each of the options listed in the final question against their own mental benchmark to determine all the instances they believe should qualify as a LLHR. The results are listed in Figure 1 below.

(Click image to enlarge.)

The double line in the middle of the table was added to easily separate those plays that received majority “yes” answers from those that received majority “no” answers. The answers in bold are those plays that qualify as a LLHR under the originally proposed definition. As a quick scan reveals, most of the scenarios listed in this question that were voted affirmatively by the majority of survey takers adhered to the originally proposed definition — and on the flip side, no play which fit the original definition was voted down by the majority of survey takers. However, two plays that had not been considered before were voted by the majority as qualifying for the Little League Home Run label, and they are both single-error plays involving the infield.

Intuitively, this makes sense: if a batter hits a ball on the infield, the expected result would be a routine out, or a routine fielder’s choice. If the batter is a fast runner, he might get an infield single. But something dramatically unusual must happen for a batter to make it all the way around the bases on such a play, even if it involves only one official error committed. Maybe the errant throw past first rolls all the way down the line and the batter runs clear around the bases before the ball can be retrieved and heaved plateward. Reasonable conjecture suggests this scenario was probably more likely to occur in the more expansive ballparks of the game’s earliest days, given the amount of foul ground they typically contained. Perhaps in the same basic bad throw scenario, when the throw back in arrives at the plate the batter-runner gets caught in a rundown between third and home before eluding a missed tag by the catcher and scoring.

Another possibility would be on a bloop pop up down the line behind first base, the ball pops out of the second baseman’s mitt on a collision with the first baseman and the ball shoots past the right fielder down the line while the batter-runner comes around to score. Yet one more would be a clean base hit to the outfield that returns a throw to the infield to make a play on a runner, but at some point an errant throw gets heaved back into the outfield which allows the batter-runner to complete his trip around the bases. All of these could fairly be classified as legitimate Little League Home Runs, even without commission of a second error.

Another possibility would be on a bloop pop up down the line behind first base, the ball pops out of the second baseman’s mitt on a collision with the first baseman and the ball shoots past the right fielder down the line while the batter-runner comes around to score. Yet one more would be a clean base hit to the outfield that returns a throw to the infield to make a play on a runner, but at some point an errant throw gets heaved back into the outfield which allows the batter-runner to complete his trip around the bases. All of these could fairly be classified as legitimate Little League Home Runs, even without commission of a second error.

Of the comments from survey takers on the one-error scenario, this one perhaps encapsulates it best: “I think if there is only one error on the play it needs to be [on] a routine [hit ball] (that a little league fielder might mess up), [i.e., not] fielding a softly hit ball and if rolling to the wall, throwing the ball back to the infield … and it going past the fielders …”

And that, right there, is the essence of the Little League Home Run. It’s not necessarily that a batter-runner happens to score on a play that was not credited as a home run, and it’s not that a big league batter crushes an extra-base hit — as they all can and that only the very best Little Leaguers could ever hope to — and happens to score on a throw past third that sails into the dugout. It’s the routine play: the little dribbler, the bloop pop-up, the ordinary single — all of which should result in nothing more than station-to-station movement at most, but which suddenly and randomly becomes a wild free-for-all because of temporary and random defensive incompetence.

And if a player does happen to hit a clean double, but comes around to score on two errors, then that too reflects a level of defensive ineptitude that, despite the big league nature of the hit, also reflects the spirit of the Little League Home Run.

Therefore, as of publication date, for the purposes of querying the Retrosheet play-by-play database to identify potential events throughout history, the definition of the Little League Home Run is revised to encompass balls put into play during which:

The batter scores, and either

-

Two errors are committed on the play; or

-

One error is committed on the play, which is not an extra-base hit, and the error is charged to a non-outfielder.

By describing the one-error plays in this way, the chance that the batter could come home on a routine error committed on a double or triple is eliminated, since it is practically impossible to produce an infield extra-base hit. However, whether the ball is hit to the infield or to the outfield, for a batter to score on a single or non-hit with only a single error charged to an infielder, it would almost certainly have to include a wild throw, or the egregious miss of a throw, that sends the ball to the outfield, thus setting off hair-on-fire desperation to retrieve and return the ball, resulting in the hilarity that is the Little League Home Run.

This also helps explain why the Bourjos play, which drew a virtual 50–50 split vote, ultimately does not fit the description of a Little League Home Run: it occurs on a routine error typical of outfielders, rather than a rare and uncommon error. And the voting results bear this out: even though almost 50% of voters voted “yes” when viewing it, when the same play in theory was flatly described in the survey question as “Outfield single and one error,” only about 34% of respondents voted yes on it; and when it was alternately described as “Ball hit to outfield and one error,” it received even fewer positive votes: 26.5%. Given this, we should continue to regard plays like the Bourjos hit not Little League Home Runs.

An Excel file listing all Little League Home Runs, as well as providing links to newspaper accounts and box scores, will be hosted by SABR at http://sabr.org/little-league-home-runs. This file can also be accessed on Google Drive at https://goo.gl/Vyo2RE, and will be updated annually as Retrosheet brings more seasons online. (NOTE: Access to newspaper accounts that are linked to within the database may require a website subscription or library membership.)

CHUCK HILDEBRANDT has served as chair of the Baseball and the Media Committee since its inception in 2013. Chuck won the 2015 Doug Pappas Award for his oral presentation “‘Little League Home Runs’ in MLB History,” and received an honorable mention for his 2014 oral presentation, “The Retroactive All-Star Game Project,” which also served as the cover story for the Spring 2015 “Baseball Research Journal.” Chuck lives with his lovely wife Terrie in Chicago, where he also plays in an adult hardball league. Chuck has also been a Chicago Cubs season ticket holder since 1999, although he is a proud native of Detroit. So, while Chuck’s checkbook may belong to the Cubs, his heart belongs to the Tigers.

Acknowledgments

The Little League Home Runs project could not have been accomplished without help along the way from some terrific people. First and foremost among them is Tom Ruane of Retrosheet, who supplied query after query after query in our quest to identify LLHRs throughout history; as well as his compatriot Mark Pankin, for helping to identify for removal certain plays that showed up in those queries but that newspaper accounts confirmed as being incorrectly scored. Also, thanks to Jacob Pomrenke of SABR and Sean Forman of Baseball-Reference.com for supplying key tools and promotional support for the project; Dave Cameron and Carson Cistulli of FanGraphs for featuring the three-part LLHR article series on the website; David W. Smith, Daniel Hirsch and Mike Emeigh, all of whom supplied Retrosheet queries early in the project; and finally, a big thanks to Patrick Gallagher, Adrian Fung, Alain Usereau, Simon Dukes, Mark Pankin (again), Bill Nowlin, Amy Watts, and Cecilia Tan for helping us nail down those last few media account confirmations of Little League Home Run plays.

Notes

1 To view or download a copy of the presentation, go to this link: https://goo.gl/dKXYJE. To hear an entertaining audio version of the presentation, go to this link: http://bit.ly/sabr45-chuck. NOTE: These links are case sensitive.

2 “SABR 45: Hildebrandt, Grilc win 2015 presentation awards,” accessed March 17, 2017, http://sabr.org/latest/sabr-45-hildebrandt-grilc-win-2015-presentation-awards.

3 “Little League Home Runs in MLB History, Part I,” accessed March 17, 2017, http://www.fangraphs.com/blogs/little-league-home-runs-in-mlb-history-part-i.

4 “The Directory of Major League Years,” accessed March 17, 2017, http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/index.html.

5 “October 26, 1911 World Series Game 6, Giants at Athletics,” accessed March 17, 2017, http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1911/B10260PHA1911.htm.

6 “Little League Home Runs in MLB History, Part II,” accessed March 17, 2017, http://www.fangraphs.com/blogs/little-league-home-runs-in-mlb-history-part-ii.

7 “Little League Home Runs in MLB History, Part III,” accessed March 17, 2017, http://www.fangraphs.com/blogs/little-league-home-runs-in-mlb-history-part-iii.

8 “Must C: Bryant’s Crazy Trip,” accessed March 17, 2017, http://m.mlb.com/video/topic/11493214/v82131183/must-c-curious-bryants-little-league-home-run.

9 The survey, currently closed, resided at https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/LLHR2015.

10 “Miguel Cabrera hits a ‘Little League’ Home Run against Colorado,” accessed March 17, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6wbVozp4qsQ (case sensitive).

11 “Bourjos’ RBI Single,” accessed March 17, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y35wMWdk1pA (case sensitive).