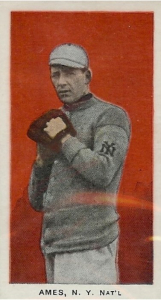

Red Ames

Red Ames’ curveball was one of the Deadball Era’s most dramatic pitches. “Ames is without question almost the hardest pitcher to catch of the professionals,” wrote the Sporting Life in 1906. “Players say no man who holds a place in the pitcher’s box is able to curve the ball so far as he can. It is a fact that he doesn’t always know himself where his curves are going to land.” Ames carried a reputation for being “very liberal with passes,” often ranking among the league leaders in walks per nine innings, and in 1905 he set a dubious modern record by uncorking 30 wild pitches. But despite his frequent bouts of wildness and a penchant for bowling, a sport that pitchers of his era generally avoided for fear it would hurt their arms, the right-hander managed to hang on for 17 seasons in the National League, compiling a 183-167 record with a 2.63 ERA. He had a knack for losing tough, close games, becoming known as the unluckiest man in baseball-his middle initial stood for “Kessling,” but to newspaper reporters and fans it would always stand for “Kalamity.”

Red Ames’ curveball was one of the Deadball Era’s most dramatic pitches. “Ames is without question almost the hardest pitcher to catch of the professionals,” wrote the Sporting Life in 1906. “Players say no man who holds a place in the pitcher’s box is able to curve the ball so far as he can. It is a fact that he doesn’t always know himself where his curves are going to land.” Ames carried a reputation for being “very liberal with passes,” often ranking among the league leaders in walks per nine innings, and in 1905 he set a dubious modern record by uncorking 30 wild pitches. But despite his frequent bouts of wildness and a penchant for bowling, a sport that pitchers of his era generally avoided for fear it would hurt their arms, the right-hander managed to hang on for 17 seasons in the National League, compiling a 183-167 record with a 2.63 ERA. He had a knack for losing tough, close games, becoming known as the unluckiest man in baseball-his middle initial stood for “Kessling,” but to newspaper reporters and fans it would always stand for “Kalamity.”

Leon Kessling Ames was born on August 2, 1882, in Warren, Ohio, the old capital of the Western Reserve in the days before Ohio became a state. Leon started pitching professionally in 1901 with Zanesville, Ohio, then went to Ilion of the New York State League for the 1902-03 seasons. In 1903 he was 12-12 with an eye-popping 221 strikeouts in 229 innings, earning a late-season trial with the New York Giants. Though the 5’10½”, 185-pound Ames was dwarfed by the tall, strapping specimens on John McGraw‘s pitching staff, he made the most of his first opportunity by tossing five hitless innings in a complete game victory against the St. Louis Cardinals in the second game of a doubleheader on September 14, 1903. The umpire called the game due to darkness and an impending storm, giving Ames an auspicious win in his major-league debut. When he pitched a complete-game five-hitter in his next start, the 21-year-old rookie put himself in good position to win a job with the Giants the following season.

After a year spent mostly as a spot-starter for the 1904 pennant-winners, Ames enjoyed his most successful season in 1905, posting a nine-game winning streak en route to a 22-8 record with a 2.74 ERA and 198 strikeouts in 262⅔ innings. In that year’s World Series, however, he pitched only one inning of relief as McGraw went with his stalwarts, Christy Mathewson and Joe McGinnity, who completely shut down the Philadelphia Athletics. Mathewson threw three shutouts in the five game series. Though Ames continued to pitch effectively for the Giants through the beginning of 1913, he never again won more than 15 games in a single season. The only year from 1905 to 1917 in which he failed to reach double digits in victories, however, was 1908. That year Ames missed several months with a kidney ailment but returned late in the season and, in the words of one reporter, “pitched as no one imagined he would ever learn to do.” Under the excruciating pressure of the most exciting pennant race in history, he won seven of eight decisions in September and October, giving the Giants a second reliable pitcher behind Mathewson. “When Ames has control—and he has it these days—there is no beating him,” wrote one New York reporter. Another wrote: “It is safe to say that McGraw and his Giants would have been in a sorry case in the last 10 days of the desperate fighting had it not been for the splendid work of Leon Ames.”

Ames was most effective in cold weather. That trait, combined with McGraw’s reluctance to pitch Mathewson on Opening Day, led to Red receiving the honor of starting the season opener three years in a row. It was in those games, however, that his hard-luck streak emerged. On April 15, 1909, he held Brooklyn hitless for nine innings at the Polo Grounds. Unfortunately for Ames, Kaiser Wilhelm of the Superbas kept the Giants’ bats almost as cold and the game went into extra innings. Ames gave up a hit to Whitey Alperman with one out in the 10th inning but kept the shutout going through the 12th. In the 13th, however, Brooklyn scored three runs to win the contest. In the 1910 opener on April 14, Ames matched up against Al Mattern, a Boston pitcher who always was tough on the Giants. Red held Boston hitless for seven innings and still held a 2-1 lead with two outs in the ninth and the bases empty. The Doves tied the game with a walk and two singles, then won it in the 11th on a Giant error. Ames’ string of bad-luck openers continued on April 12, 1911, when he held the Phillies hitless for six innings and scoreless for eight. With two out in the ninth, Fred Luderus doubled home the only two runs of the game to win it for the Phils and Earl Moore, who had stymied the Giants completely.

“Leon Ames stacks up against the toughest luck of any pitcher in the big show,” claimed the New York Times on August 13, 1911. The day before, Ames had lost a tough game to Philadelphia, 2-0, at the Polo Grounds, dropping his record to 5-9. In four of those losses, the Giants scored two runs or less. The Times pleaded: “Won’t someone please send Mr. Ames the left hind foot of a churchyard rabbit, a few swastika pins and some old rusty horseshoes?” (Before its adoption by the Nazi party, the swastika was considered a good-luck symbol.) According to Mathewson’s book, Pitching in a Pinch (ghost-written by John Wheeler), Ames was discouraged on the eve of the Giants’ final western road trip. “I don’t see any use in taking me along, Mac,” he told McGraw. “The club can’t win with me pitching if the other guys don’t even get a foul.” Red went along anyway, and in his mail on September 11 he received a necktie and four-leaf clover sent by an unnamed “prominent actress.” Ames was to wear the tie with his street clothes and conceal it within his uniform during games. The necktie “would have done for a headlight,” noted Mathewson, “and made Joseph’s coat of many colors look like a mourning garment.” Still, Ames followed instructions and won easily on a chilly September 13. That night at dinner he pointed to the tie and declared, “I don’t change her until I lose.” The Giants posted a sparkling 19-4 record on that road trip, all but ensuring the pennant, with Ames contributing four victories in five starts (the Giants won the fifth start, in St. Louis, in the 10th inning). “And all of the time,” wrote Mathewson, “he wore that spectrum around his collar for a necktie. As it frayed with the wear and tear, more colors began to show, although I didn’t think it possible. If he had had occasion to put on his evening clothes, I believe that tie would have gone with it.”

Ames was a solid contributor to the 1911-12 pennant-winners, taking his turn in the rotation in cool weather and pitching in relief as temperatures rose. On May 22, 1913, the Giants sent him, Heinie Groh, Josh Devore, and $20,000 to the Reds in exchange for Art Fromme and, a few weeks later, Eddie Grant. Red started regularly in Cincinnati and pitched well for a couple of years, hurling a career-high 297 innings in 1914 when he posted a 15-23 record and contributed a league-leading six saves. After a poor start in 1915 caused his sale to St. Louis on July 24, Ames became the Cardinals’ most effective pitcher during the second half, going 9-3 with a 2.46 ERA. He remained a valuable member of their pitching staff through the end of the 1918 season, starting as well as relieving and leading the league in saves again with eight in 1916. Time finally caught up with the 36-year-old Ames in 1919 when he split the season between St. Louis and Philadelphia and was pounded for 114 hits in 86 innings.

The Phillies returned Red Ames to St. Louis after the 1919 season, but the Cardinals gave him his unconditional release when he was involved in a serious automobile accident during the off-season. Red caught on with Kansas City of the American Association, winning a combined 33 games in 1920-21 before drawing his release early in 1922. He pitched briefly for Daytona Beach of the Florida State League in 1923 before retiring to his hometown of Warren. Leon and his wife, Rena, had one son, Leon Jr., who pitched in the minors for Wichita, Salisbury, and Durham before retiring from baseball in 1929. While working for a Warren dairy company, Leon Sr. damaged his lungs when he accidentally inhaled ammonia fumes emanating from a defective drum. After a lingering illness, Red died on October 8, 1936, at the age of 54. Three years later, Rena Ames received $6,500 in compensation from the Ohio Industrial Commission.

An earlier version of this biography appeared in Tom Simon, ed., “Deadball Stars of the National League” (Washington, D. C.: Brassey’s Inc., 2004).

Sources

The Baseball Chronology (CBS Sportsline).

Clipping files for Leon K. Ames from the National Baseball Library and the Sporting News archives.

Keener, Sid C. “Leon Ames, Dean of Pitchers, Tells How He Keeps Going.” Photocopy of newspaper clipping, dated 4-11-1918 (newspaper not available).

Mathewson, Christy. Pitching in a Pinch: Baseball from the Inside. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1994. (Reprinted from original edition of 1912.)

Newspaper articles, New York Times, 1903-13.

Obituary from the New York Herald-Tribune, 10-09-1936.

Full Name

Leon Kessling Ames

Born

August 2, 1882 at Warren, OH (USA)

Died

October 8, 1936 at Warren, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.