Jackie Robinson’s Signing: The Real Story

This article was written by Jules Tygiel - John Thorn

This article was published in From Rube to Robinson: SABR’s Best Articles on Black Baseball (2021)

This article was selected for inclusion in SABR 50 at 50: The Society for American Baseball Research’s Fifty Most Essential Contributions to the Game.

Author’s note: Jules Tygiel and I collaborated on this story for SPORT magazine in June 1988. Subsequently it appeared in SABR’s The National Pastime, in several editions of Total Baseball, and in Jules’s Extra Bases: Reflections on Jackie Robinson, Race, and Baseball History. Despite this drumbeat of evidence, the legend surrounding Jackie Robinson’s signing has persisted. Jules and I believed that the real story was not only more interesting than the schoolboy version but also made Jackie’s pioneering mission even more heroic. — John Thorn

October 1945. As the Detroit Tigers and Chicago Cubs faced off in the World Series, photographer Maurice Terrell arrived at an almost deserted minor-league park in San Diego, California, to carry out a top-secret assignment: to surreptitiously photograph three Black baseball players.

Terrell shot hundreds of motion-picture frames of Jackie Robinson and the two other players. A few photos appeared in print but the existence of the additional images remained unknown for four decades. In April 1987, as Major League Baseball prepared a lavish commemoration of the fortieth anniversary of Robinson’s debut, I unearthed a body of contact sheets and unprocessed film from a previously unopened carton donated in 1954 by Look magazine to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. This discovery triggered an investigation which led to startling revelations regarding Branch Rickey, the president of the Brooklyn Dodgers, and his signing of Jackie Robinson to shatter baseball’s longstanding color line; the relationship between these two historic figures; and the stubbornly controversial issue of Black managers in baseball.

The popular “frontier” image of Jackie Robinson as a lone gunman facing down a hostile mob has always dominated the story of the integration of baseball. But new information related to the Terrell photos reveals that while Robinson was the linchpin in Branch Rickey’s strategy, in October 1945 Rickey intended to announce the signing of not just Jackie Robinson, but of several other Negro League stars. Political pressure, however, forced Rickey’s hand, thrusting Robinson alone into the spotlight. And in 1950, after only three years in the major leagues, Robinson pressed Rickey to consider him for a position as field manager or front-office executive, raising an issue with which the baseball establishment grappled long after.

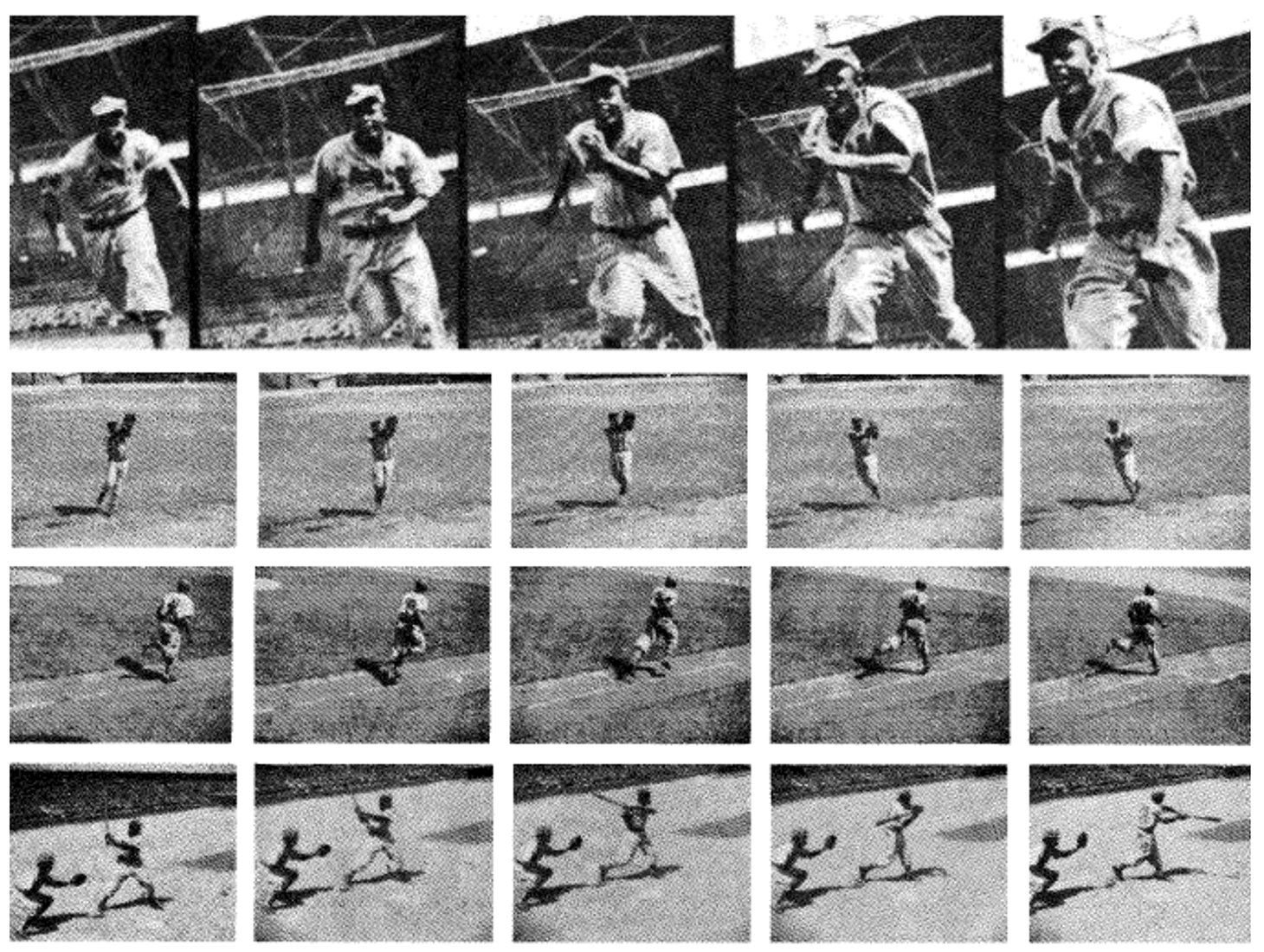

The story of these revelations began with the discovery of the Terrell photographs. The photos show a youthful, muscular Robinson in a battered cap and baggy uniform fielding from his position at shortstop, batting with a Black catcher crouched behind him, trapping a third Black player in a rundown between third and home, and sprinting along the basepaths more like a former track star than a baseball player. All three players wore uniforms emblazoned with the name “Royals.” A woman with her back to the action is the only figure visible amid the vacant stands. The contact sheets are dated October 7, 1945.

The photos were perplexing. The momentous announcement of Jackie Robinson’s signing with the Montreal Royals took place on October 23, 1945. Before that date his recruitment had been a tightly guarded secret. Why, then, had a Look photographer taken such an interest in Robinson two weeks earlier? Where had the pictures been taken? And why was Robinson already wearing a Royals uniform?

I called Jules Tygiel, the author of Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy, to see if he could shed some light on the photos. Tygiel knew nothing about them, but he did have in his files a 1945 manuscript by newsman Arthur Mann, who frequently wrote for Look. The article, drafted with Rickey’s cooperation, had been intended to announce the Robinson signing but had never been published. The pictures, Jules and I concluded, were to have accompanied Mann’s article; we decided to find out the story behind the photo session.

The clandestine nature of the photo session did not surprise us. From the moment he had arrived in Brooklyn in 1942, determined to end baseball’s Jim Crow traditions, Rickey had feared that premature disclosure of his intentions might doom his bold design. No Blacks had appeared in the major leagues since 1884 when two brothers, Welday and Moses Fleetwood Walker, had played for Toledo in the American Association. [In recent years an earlier African American major leaguer has been identified: William Edward White, a one-game first baseman for Providence of the National League in 1879.] Not since the 1890s had Black players appeared on a minor-league team. During the ensuing half-century all-Black teams and leagues featuring legendary figures like pitcher Satchel Paige and catcher Josh Gibson had performed on the periphery of White organized baseball.

Baseball executives, led by Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, had strictly policed the color line, barring Blacks from both major and minor leagues. Rickey therefore moved slowly and secretly to explore the issue and cover up his attempts to scout Black players during his first three years in Brooklyn. He informed the Dodger owners of his plans but took few others into his confidence.

In the spring of 1945, as Rickey prepared to accelerate his scouting efforts, advocates of integration, emboldened by the impending end of World War II and the recent death of Commissioner Landis, escalated their campaign to desegregate baseball. On April 6, 1945, Black sportswriter Joe Bostic appeared at the Dodgers’ Bear Mountain training camp with Negro League stars Terris McDuffie and Dave “Showboat” Thomas and forced Rickey to hold tryouts for the two players. Ten days later Black journalist Wendell Smith, White sportswriter Dave Egan, and Boston city councilman Isidore Muchnick engineered an unsuccessful ninety-minute audition with the Red Sox for Robinson, then a shortstop with the Kansas City Monarchs; second baseman Marvin Williams of the Philadelphia Stars; and outfielder Sam Jethroe of the Cleveland Buckeyes. In response to these events the major leagues announced the formation of a Committee on Baseball Integration. (Reflecting White baseball’s true intentions on the matter, the group never met.)

In the face of this heightened activity, Rickey created an elaborate smokescreen to obscure his scouting of Black players. In May 1945 he announced the formation of a new franchise, the Brooklyn Brown Dodgers, and a new Negro League, the United States League. Rickey then dispatched his best talent hunters to observe Black ballplayers, ostensibly for the Brown Dodgers, but in reality for the Brooklyn National League club.

A handwritten memorandum in the Rickey Papers at the Library of Congress offers a rare glimpse of Rickey’s emphasis on secrecy in his instructions to Dodger scouts. The document, signed “Chas. D. Clark” and accompanied by a Negro National League schedule for April-May 1945, is headlined “Job Analysis,” and defines the following “Duties: under supervision of management of club”:

- To establish contact (silent) with all clubs (local or general).

- To gain knowledge and [sic] abilities of all players.

- To report all possible material (players).

- Prepare weekly reports of activities.

- Keep composite report of outstanding players . . . To travel and cover player whenever management so desire.

Clark’s “Approch” [sic] was to “Visit game and loose [sic] self in stands; Keep statistical report (speed, power, agility, ability, fielding, batting, etc.) by score card”; and “Leave immediately after game.”

Clark’s directions, however, contain one major breach in Rickey’s elaborate security precautions. According to his later accounts, Rickey had told most Dodger scouts that they were evaluating talent for a new “Brown Dodger” franchise. But Clark’s first “Objective” was “To Cover Negro teams for possible major league talent.” Had Rickey confided in Clark, a figure so obscure as to escape prior mention in the voluminous Robinson literature? Dodger superscout and Rickey confidante Clyde Sukeforth had no recollection of Clark when Jules spoke with him, raising the possibility that Clark was not part of the Dodger family, but perhaps someone connected with Black baseball. Had Clark himself interpreted his instructions in this manner?

Whatever the answer, Rickey successfully diverted attention from his true motives. Nonetheless, mounting interest in the integration issue threatened Rickey’s careful planning. In the summer of 1945 Rickey constructed yet another facade. The Dodger president took into his confidence Dan Dodson, a New York University sociologist who chaired Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia’s Committee on Unity and requested that Dodson form a Committee on Baseball ostensibly to study the possibility of integration. In reality, the committee would provide the illusion of action while Rickey quietly completed his own preparations. “This was one of the toughest decisions I ever had to make while in office,” Dodson later confessed. “The major purpose I could see for the committee was that it was a stall for time. . . . Yet had Mr. Rickey not delivered . . . I would have been totally discredited.”

Thus by late August, even as Rickey’s extensive scouting reports had led him to focus on Jackie Robinson as his standard bearer, few people in or out of the Dodger organization suspected that a breakthrough was imminent. On August 28 Rickey and Robinson held their historic meeting at the Dodgers’ Montague Street offices in downtown Brooklyn. Robinson signed an agreement to accept a contract with the Montreal Royals, the top Dodger affiliate, by November 1.

Rickey, still concerned with secrecy, impressed upon Robinson the need to maintain silence. Robinson could tell the momentous news to his family and fiancée, but no one else. For the conspiratorial Rickey, keeping the news sheltered while continuing arrangements required further subterfuge. Rumors about Robinson’s visit had already spread through the world of Black baseball. To stifle speculation Rickey “leaked” an adulterated version of the incident to Black sportswriter Wendell Smith. Smith, who had recommended Robinson to Rickey and advised Rickey on the integration project, doubtless knew the true story behind the meeting. On September 8, however, he reported in the Pittsburgh Courier that the “sensational shortstop” and “colorful major-league dynamo” had met behind “closed doors. . . . The nature of the conference has not been revealed,” Smith continued. Rickey claimed that he and Robinson had assessed “the organization of Negro baseball,” but Smith noted that “it does not seem logical [Rickey] should call in a rookie player to discuss the future organization of Negro baseball.” He closed with the tantalizing thought that “it appears that the Brooklyn boss has a plan on his mind that extends further than just the future of Negro baseball as an organization.” The subterfuge succeeded. Neither Black nor White reporters pursued the issue.

Rickey, always sensitive to criticism by New York sports reporters and understanding the historic significance of his actions, also wanted to be sure that his version of the integration breakthrough and his role in it be accurately portrayed. To guarantee this he persuaded Arthur Mann, his close friend and later a Dodger employee, to write a 3,000-word manuscript to be published simultaneously with the announcement of the signing.

Part Two

Although it was impossible to confirm in 1987, when I found Maurice Terrell’s photos, it seemed to Jules and me highly likely that, inasmuch as they had been commissioned by Look, they were destined to accompany Mann’s article. (Once we located Terrell himself, he confirmed the linkage.) Clearer prints of the negatives revealed that Terrell had taken the pictures in San Diego’s Lane Stadium. This fit in with Robinson’s autumn itinerary. After his August meeting with Rickey, Robinson had returned briefly to the Kansas City Monarchs. With the Dodger offer securing his future and the relentless bus trips of the Negro League schedule wearing him down, he left the Monarchs before season’s end and returned home to Pasadena, California. In late September he hooked up with Chet Brewer’s Kansas City Royals, a postseason barnstorming team which toured the Pacific Coast, competing against other Negro League teams and major- and minor-league all-star squads. Thus the word “Royals” on Robinson’s uniform, which had so piqued our interest as a seeming anomaly, ironically turned out to relate not to Robinson’s future team in Montreal, but rather to his interim employment in California.

Although it was impossible to confirm in 1987, when I found Maurice Terrell’s photos, it seemed to Jules and me highly likely that, inasmuch as they had been commissioned by Look, they were destined to accompany Mann’s article. (Once we located Terrell himself, he confirmed the linkage.) Clearer prints of the negatives revealed that Terrell had taken the pictures in San Diego’s Lane Stadium. This fit in with Robinson’s autumn itinerary. After his August meeting with Rickey, Robinson had returned briefly to the Kansas City Monarchs. With the Dodger offer securing his future and the relentless bus trips of the Negro League schedule wearing him down, he left the Monarchs before season’s end and returned home to Pasadena, California. In late September he hooked up with Chet Brewer’s Kansas City Royals, a postseason barnstorming team which toured the Pacific Coast, competing against other Negro League teams and major- and minor-league all-star squads. Thus the word “Royals” on Robinson’s uniform, which had so piqued our interest as a seeming anomaly, ironically turned out to relate not to Robinson’s future team in Montreal, but rather to his interim employment in California.

For further information Jules contacted Chet Brewer, who at age eighty still lived in Los Angeles. Brewer, one of the great pitchers of the Jim Crow era, had known Robinson well. He had followed Robinson’s spectacular athletic career at UCLA and in 1945 they became teammates on the Monarchs. “Jackie was major-league all the way,” recalled Brewer. “He had the fastest reflexes I ever saw in a player.”

Robinson particularly relished facing major-league all-star squads. Against Bob Feller, Robinson once slashed two doubles. “Jack was running crazy on the bases,” a Royals teammate remembered. In one game he upended Gerry Priddy, Washington Senators infielder. Priddy angrily complained about the hard slide in an exhibition game. “Any time I put on a uniform,” retorted Robinson, “I play to win.”

Brewer recalled that Robinson and two other Royals journeyed from Los Angeles to San Diego on a day when the team was not scheduled to play. He identified the catcher in the photos as Buster Haywood and the other player as Royals third baseman Herb Souell. Souell was no longer living, but Haywood, who like Brewer lived in Los Angeles, vaguely recalled the event, which he incorrectly remembered as occurring in Pasadena. Robinson recruited the catcher and Souell, his former Monarch teammate, to “work out” with him. All three wore their Kansas City Royals uniforms. Haywood found neither Robinson’s request nor the circumstances unusual. Although he was unaware that they were being photographed, Haywood described the session accurately. “We didn’t know what was going on,” he stated. “We’d hit and throw and run from third base to home plate.”

The San Diego pictures provide a rare glimpse of the pre-Montreal Robinson. The article which they were to accompany and related correspondence in the Library of Congress offer even more rare insights into Rickey’s thinking. The unpublished Mann manuscript was entitled “The Negro and Baseball: The National Game Faces a Racial Challenge Long Ignored.” As Mann doubtless based his account on conversations with Rickey and since Rickey’s handwritten comments appear in the margin, it stands as the earliest “official” account of the Rickey-Robinson story and reveals many of the concerns confronting Rickey in September 1945.

One of the most striking features of the article is the language used to refer to Robinson. Mann, reflecting the racism typical of postwar America, portrays Robinson as the “first Negro chattel in the so-called National pastime.” At another point he writes, “Rickey felt the boy’s sincerity,” appropriate language perhaps for an eighteen-year-old prospect, but not for a twenty-six-year-old former Army officer.

“The Negro and Baseball” consists largely of the now familiar Rickey-Robinson story. Mann recreated Rickey’s haunting 1904 experience as collegiate coach when one of his Black baseball players, Charlie Thomas, was denied access to a hotel. Thomas cried and rubbed his hands, chanting, “Black skin! Black skin! If I could only make ’em White.” Mann described Rickey’s search for the “right” man, the formation of the United States League as a cover for scouting operations, the reasons for selecting Robinson, and the fateful Rickey-Robinson confrontation. Other sections, however, graphically illustrate additional issues Rickey deemed significant. Mann repeatedly cites the costs the Dodgers incurred: $5,000 to scout Cuba, $6,000 to scout Mexico, $5,000 to establish the “Brooklyn Brown Dodgers.” The final total reaches $25,000, a modest sum considering the ultimate returns, but one sufficiently large that Rickey must have felt it would counter his skinflint image.

Rickey’s desire to show that he was not motivated by political pressures also emerges clearly. Mann had suggested that upon arriving in Brooklyn in 1942, Rickey “was besieged by telephone calls, telegrams and letters of petition in behalf of Black ball players,” and that this “staggering pile of missives [was] so inspired to convince him that he and the Dodgers had been selected as a kind of guinea pig.” In his marginal comments, Rickey vehemently wrote “No!” in a strong dark script. “I began all this as soon as I went to Brooklyn.” Explaining why he had never attacked the subject during his two decades as general manager of the St. Louis Cardinals, Rickey referred to the segregation in that city. “St. Louis never permitted Negro patrons in the grandstand,” he wrote, describing a policy he apparently had felt powerless to change.

Mann also devoted two of his twelve pages to a spirited attack on the Negro Leagues, repeating Rickey’s charges that “they are the poorest excuse for the word league” and documented the prevalence of barnstorming, the uneven scheduling, absence of contracts, and dominance of booking agents. Mann revealingly traces Rickey’s distaste for the Negro Leagues to the “outrageous” guarantees demanded by New York booking agent William Leuschner to place Black teams in Ebbets Field while the Dodgers were on the road.

Rickey’s misplaced obsession with the internal disorganization of the Negro Leagues had substantial factual basis. But Rickey had an ulterior motive. In his September 8 article, Wendell Smith addressed the issue of “player tampering,” asking, “Would [Rickey] not first approach the owners of these Negro teams who have these stars under contract?” Rickey, argued Smith in what might have been an unsuccessful preemptive strike, “is obligated to do so and his record as a businessman indicated that he would.” As Smith may have known, Rickey maintained that Negro League players did not sign valid contracts and so became free agents at the end of each season. Thus the Mahatma had no intention of compensating Negro League teams for the players he signed. His repeated attacks on Black baseball, including those in the Mann article, served to justify this questionable position.

The one respect in which “The Negro and Baseball” departs radically from the common picture of the Robinson legend is in its report of Robinson as one of a group of Blacks about to be signed by the Dodgers. Mann’s manuscript and subsequent correspondence from Rickey reveal that Rickey did not intend for Robinson to withstand the pressures alone. “Determined not to be charged with merely nibbling at the problem,” wrote Mann, “Rickey went all out and brought in two more Negro players,” and “consigned them, with Robinson, to the Dodgers’ top farm club, the Montreal Royals.” Mann named pitcher Don Newcombe and, surprisingly, outfielder Sam Jethroe as Robinson’s future teammates. Whether the recruitment of additional Blacks had always been Rickey’s intention or whether he had reached his decision after meeting with Robinson in August is unclear. But by late September, when he provided information to Mann for his article, Rickey had clearly decided to bring in other Negro League stars.

During the first weekend in October, Dodger coach Chuck Dressen fielded a major-league all-star team in a series of exhibition games against Negro League standouts at Ebbets Field. Rickey took the opportunity to interview at least three Black pitching prospects—Newcombe, Roy Partlow, and John Wright. The following week he met with catcher Roy Campanella. Campanella and Newcombe, at least, believed they had been approached to play for the “Brown Dodgers.”

At the same time, Rickey decided to postpone publication of Mann’s manuscript. In a remarkable letter sent from the World Series in Chicago on October 7, Rickey informed Mann:

We just can’t go now with the article. The thing isn’t dead—not at all. It is more alive than ever and that is the reason we can’t go with any publicity at this time. There is more involved in the situation than I had contemplated. Other players are in it and it may be that I can’t clear these players until after the December meetings, possibly not until after the first of the year. You must simply sit in the boat. . . .

There is a November 1 deadline on Robinson,—you know that. I am undertaking to extend that date until January 1st so as to give me time to sign plenty of players and make one break on the complete story. Also, quite obviously it might not be good to sign Robinson with other and possibly better players unsigned.

The revelations and tone of this letter surprised Robinson’s widow, Rachel, forty years after the event. Rickey “was such a deliberate man,” she recalled in our conversation, “and this letter is so urgent. He must have been very nervous as he neared his goal. Maybe he was nervous that the owners would turn him down and having five people at the door instead of just one would have been more powerful.”

Events in the weeks after October 7 justified Rickey’s nervousness and forced him to deviate from the course stated in the Mann letter. Candidates in New York City’s upcoming November elections, most notably Black Communist City Councilman Ben Davis, made baseball integration a major issue in the campaign. Mayor LaGuardia’s Democratic party also sought to exploit the issue. The Committee on Baseball had prepared a report outlining a modest, long-range strategy for bringing Blacks into the game and describing the New York teams, because of the favorable political and racial climate in the city, as in a “choice position to undertake this pattern of integration.” LaGuardia wanted Rickey’s permission to make a pre-election announcement that, as a result of the committee’s work, “baseball would shortly begin signing Negro players.”

Rickey, a committee member, had long since subverted the panel to his own purposes. By mid-October, however, the committee had become “an election football.” Again unwilling to risk the appearance of succumbing to political pressure and thereby surrendering what he viewed as his rightful role in history, Rickey asked LaGuardia to delay his comments. Rickey hurriedly contacted Robinson, who had joined a barnstorming team in New York en route to play winter ball in Venezuela and dispatched him instead to Montreal. On October 23, 1945, with Rickey’s carefully laid plans scuttled, the Montreal Royals announced the signing of Robinson, and Robinson alone.

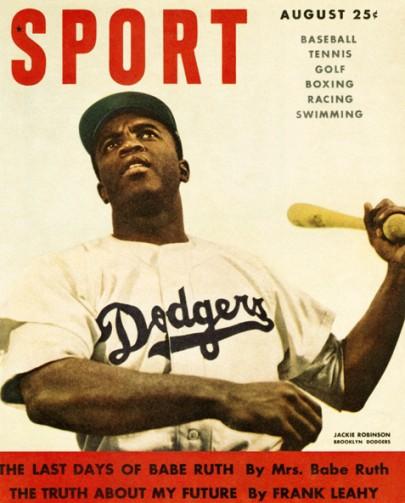

Mann’s article never appeared. Look, having lost its exclusive, published two strips of the Terrell pictures in its November 27, 1945, issue accompanying a brief summary of the Robinson story, which was by then old news. The unprocessed film and contact sheets were loaded into a box and nine years later shipped to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, where they remained, along with a picture of Jethroe, unpacked until April 1987.

Part Three

Newcombe, Campanella, Wright, and Partlow all joined the Dodger organization in the spring of 1946. Jethroe became a victim of the “deliberate speed” of baseball integration. Rickey did not interview Jethroe in 1945. Since few teams followed the Dodger lead, the fleet, powerful outfielder remained in the Negro Leagues until 1948, when Rickey finally bought his contract from the Cleveland Buckeyes for $5,000. Jethroe had two spectacular seasons at Montreal before Rickey, fearing a “surfeit of colored boys on the Brooklyn club,” profitably sold him to the Boston Braves for $100,000. Jethroe won the Rookie of the Year Award in 1950, but his delayed entry into White baseball foreshortened what should have been a stellar career. Until I informed him of how he had been part of Rickey’s 1945 plan, Jethroe had been unaware of how close he had come to joining Robinson, Newcombe, and Campanella in the pantheon of integration pioneers.

Newcombe, Campanella, Wright, and Partlow all joined the Dodger organization in the spring of 1946. Jethroe became a victim of the “deliberate speed” of baseball integration. Rickey did not interview Jethroe in 1945. Since few teams followed the Dodger lead, the fleet, powerful outfielder remained in the Negro Leagues until 1948, when Rickey finally bought his contract from the Cleveland Buckeyes for $5,000. Jethroe had two spectacular seasons at Montreal before Rickey, fearing a “surfeit of colored boys on the Brooklyn club,” profitably sold him to the Boston Braves for $100,000. Jethroe won the Rookie of the Year Award in 1950, but his delayed entry into White baseball foreshortened what should have been a stellar career. Until I informed him of how he had been part of Rickey’s 1945 plan, Jethroe had been unaware of how close he had come to joining Robinson, Newcombe, and Campanella in the pantheon of integration pioneers.

For Robinson, who had always occupied center stage in Rickey’s thinking, the early announcement intensified the pressures and enhanced the legend. The success or failure of integration rested disproportionately on his capable shoulders. He became the lightning rod for supporters and opponents alike, attracting the responsibility, the opprobrium and ultimately the acclaim for his historic achievement.

Beyond these revelations about the Robinson signing, the Library of Congress documents add surprisingly little to the familiar story of the integration of baseball. The Rickey Papers copiously detail his post-Dodger career as general manager of the Pittsburgh Pirates, but are strangely silent about the critical period of 1944 to 1948. Records for these years probably remained with the Dodger organization, which in 1988 claimed to have no knowledge of their whereabouts. National League Office documents for these years have remained closed to the public.

In light of the controversy engendered by former Dodger General Manager Al Campanis’s remarks about Blacks in management, however, one exchange between Rickey and Robinson becomes particularly relevant. In 1950, after his fourth season with the Dodgers, Robinson appears to have written Rickey about the possibility of employment in baseball when his playing days ended. Robinson’s original letter cannot be found in either the Rickey papers or the Robinson family archives. However, Rickey’s reply, dated December 31, 1950, survives. Rickey, who had recently left the Dodgers after an unsuccessful struggle to wrest control of the team from Walter O’Malley, responded to Robinson’s inquiry with a long and equivocal answer.

“It is not at all because of lack of appreciation that I have not acknowledged your good letter of some time ago,” Rickey began. “Neither your writing, nor sending the letter, nor its contents gave me very much surprise.” On the subject of managing, Rickey replied optimistically, “I hope that the day will soon come when it will be entirely possible, as it is entirely right, that you can be considered for administrative work in baseball, particularly in the direction of field management.” Rickey claimed to have told several writers that “I do not know of any player in the game today who could, in my judgment, manage a major-league team better than yourself,” but that the news media had inexplicably ignored these comments.

Yet Rickey tempered his encouragement with remarks that to a reader today seem gratuitous. “As I have often expressed to you,” he wrote, “I think you carry a great responsibility for your people . . . and I cannot close this letter without admonishing you to prepare yourself to do a widely useful work, and, at the same time, dignified and effective in the field of public relations. A part of this preparation, and I know you are smiling, for you have already guessed my oft repeated suggestion—to finish your college course meritoriously and get your degree.” This advice, according to Rachel Robinson, was a “matter of routine” between the two men ever since their first meeting. Nonetheless, to the thirty-one-year-old Robinson, whose non-athletic academic career had been marked by indifferent success and whose endorsements and business acumen had already established the promise of a secure future, Rickey’s response may have seemed to beg the question.

Rickey concluded with the promise, which seems to hinge on the completion of a college degree, that “It would be a great pleasure for me to be your agent in placing you in a big job after your playing days are finished. Believe me always.” Shortly after writing this letter Rickey became the general manager of the Pittsburgh Pirates. Had Robinson ended his playing career before Rickey left the Pirates, perhaps the Mahatma would have made good on his pledge. But Rickey resigned from the Pirates at the end of the 1955 season, one year before Robinson’s retirement, and never again had the power to hire a manager.

Robinson’s 1950 letter to Rickey marked only the beginning of his quest to see a Black manager in the major leagues. In 1952 he hoped to gain experience by managing in the Puerto Rican winter league, but, according to the New York Post, Commissioner Happy Chandler withheld his approval, forcing Robinson to cancel his plans. On November 30, 1952, the Dodgers star raised the prospect of a Black manager in a televised interview on Youth Wants to Know, stating that both he and Campanella had been “approached” on the subject. In 1954, after the Dodgers had fired manager Chuck Dressen, speculation arose that either Robinson or Pee Wee Reese might be named to the post. But the team bypassed both men and selected veteran minor-league manager Walter Alston, who went on to hold the job for more than two decades.

pon his retirement in 1956, Robinson, who had begun to manifest signs of the diabetes that would plague the rest of his life, had lost much of his enthusiasm for the prospect of managing, but nonetheless would probably have accepted another pioneering role. “He had wearied of the travel,” Rachel Robinson stated, “and no longer wanted to manage. He just wanted to be asked as a recognition of his accomplishments, his abilities as a strategist, and to show that White men could be led by a Black.”

Ironically, in the early years of integration White baseball had bypassed a large pool of qualified and experienced Black managers: former Negro League players and managers like Chet Brewer, Ray Dandridge, and Quincy Trouppe. In the early 1950s Brewer and several other Negro League veterans managed all-Black minor-league teams, but no interracial club at any level offered a managerial position to a Black until 1961, when former Negro League and major-league infielder Gene Baker assumed the reins of a low-level Pittsburgh Pirate farm team, one of only three Blacks to manage a major-league affiliate before 1975.

This lack of opportunity loomed as a major frustration for those who had broken the color line. “We bring dollars into club treasuries while we play,” protested Larry Doby, the first Black American Leaguer, in 1964, “but when we stop playing, our dollars stop. When I retired in ’59 I wanted to stay in the game, to be a coach or in some other capacity, or to manage in the minors until I’d qualify for a big-league job. Baseball owners are missing the boat by not considering Negroes for such jobs.” Monte Irvin, who had integrated the New York Giants in 1949 and clearly possessed managerial capabilities, concurred. “Among retired and active players [there] are Negroes with backgrounds suited to these jobs,” wrote Irvin. “Owning a package liquor store, bowling alley or selling insurance is hardly the vocation for an athlete who has accumulated a lifetime knowledge of the game.”

Had Robinson, Doby, Irvin, or another Black been offered a managerial position in the 1950s or early 1960s, and particularly if the first Black manager had experienced success, it is possible that this would have opened the doors for other Black candidates. As with Robinson’s ascension to the major leagues, this example might ultimately have made the hiring and firing of a Black manager more or less routine. Robinson dismissed the notion that a Black manager might experience extraordinary difficulties. “Many people believe that White athletes will not play for a Negro manager,” he argued in 1964. “A professional athlete will play with or for anyone who helps him make more money. He will respect ability, first, last, and all the time. This is something that baseball’s executives must learn—that any experienced player with leadership qualities can pilot a ballclub to victory, no matter what the color of his skin.”

On the other hand, the persistent biases of major-league owners and their subsequent history of discriminatory hiring indicated that the solitary example of a Jackie Robinson regime would probably not have been enough to shake the complacency of the baseball establishment. Few baseball executives considered hiring Blacks as managers even in the 1960s and 1970s. In 1960 Chicago White Sox owner Bill Veeck, who had hired Doby in 1947 and represented the most enlightened thinking in the game, raised the issue, but even Veeck defined special qualifications needed for a Black to manage. “A man will have to have more stability to be a Negro coach or manager and be slower to anger than if he were White,” stated Veeck. “The first major-league manager will have to be a fellow who has been playing extremely well for a dozen years or so, so that he becomes a byword for excellence.” The following year Veeck sold the White Sox; other owners ignored the issue entirely.

Jackie Robinson himself never flagged in his determination to see a Black manager. In 1972, at the World Series at Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati, baseball commemorated the twenty-fifth anniversary of his major-league debut. A graying, almost blind, but still defiant Robinson told a nationwide television audience, “I’d like to live to see a Black manager.”

“I would have eagerly welcomed the challenge of a managerial job before I left the game,” Robinson revealed in his 1972 autobiography, I Never Had It Made. “I know I could have been a good manager.” But despite his obvious qualifications, no one offered him a job.

On Opening Day 1975, African American star player Frank Robinson took the reins of the Cleveland Indians. But Jackie had not lived to see that; he died nine days after his remarks at the 1972 World Series.

JOHN THORN is the author and editor of numerous books, including Total Baseball: The Official Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball, Total Football: The Official Encyclopedia of Major League Football, Treasures of the Baseball Hall of Fame, The Hidden Game of Baseball, The Glory Days: New York Baseball 1947–1957, and The Armchair Book of Baseball. His 2011 book, Baseball in the Garden of Eden: The Secret History of the Early Game, published by Simon & Schuster, was an in-depth chronicle of the seminal development and pioneers of the sport. A New York Times review of the latter book referred to Thorn as “a researcher of colossal diligence.” Thorn served as the senior creative consultant for the 1994 Ken Burns documentary Baseball. On March 1, 2011, he was named Official Baseball Historian for Major League Baseball. Thorn is the recipient of the 2006 Bob Davids award and the 2013 Henry Chadwick award.

JULES TYGIEL (1949-2008) made his most lasting re- search contribution for his classic 1983 book, Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy. A sweeping history of the integration of the game focusing on Robinson through the 1950s, with a firm grasp of the American narrative as well as a central baseball personality, the book is often cited as one of the best in sports literature. A professor of history at San Francisco State University, Tygiel wrote in the introduction to Great Experiment, “Writing this book has allowed me to combine my vocation as a historian and my avocation as a baseball fanatic.” Tygiel wrote books and articles on many subjects, but often returned to his favorite sport. His book Past Time: Baseball as History (2001) won SABR’s Seymour Medal as the best book of baseball writing that year. Tygiel is winner of the 2010 Henry Chadwick Award.